Prophet of Postmodernism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logic I Format: Work Text (Digital Available August 2016)

Logic I Format: Work Text (Digital Available August 2016) Course Objective The Logic I course introduces students to the science and art of right thinking or reasoning through the use of informal logic. After a short survey of the contributions of Greek philosophers, students will dive into an extended study of logical fallacies of relevance, presumption, and clarity. Fallacies include ad hominem personal attacks, appeals to fear, red herrings, equivocation, and sweeping generalizations. Students will analyze arguments and everyday conversations in order to identify and counter fallacies. The course concludes with an investigation into the principles of argumentative dialogue and the impact of language and emotions in debate. Course Prerequisites or Corequisites None Unit 1: Reasoning Understand that logic is “right thinking or reasoning.” Understand that logic is a wide field involving art, science, and skill. Recognize the contribution of Greek philosophers, Socrates and Aristotle, to the establishment of logic as a field of study. Understand the importance of logic in a classical education. Distinguish the difference between formal logic and informal logic. Compare and contrast inductive and deductive reasoning. Define fallacy. Recognize and analyze fallacious arguments of relevance. Recognize and describe ad hominem abusive fallacies. Recognize and describe ad hominem circumstantial fallacies. Recognize and describe tu quoque fallacies. Recognize and describe genetic fallacies. Recognize and describe mob appeal fallacies. Recognize and understand the subtle difference between an appeal to belief and an appeal to popularity. Recognize and describe snob appeal fallacies. Unit 2: The Contrast Recognize, classify, and describe an appeal to fear. Recognize and describe the appeal to force as a variation of the appeal to fear. -

Fallacies of Relevance1

1 Phil 2302 Logic Dr. Naugle Fallacies of Relevance1 "Good reasons must, of force, give place to better." —Shakespeare "There is a mighty big difference between good, sound reasons, and reasons that sound good." —Burton Hillis "It would be a very good thing if every trick could receive some short and obviously appropriate name, so that when a man used this or that particular trick, he could at once be reproved for it." —Arthur Schopenhauer Introduction: There are many ways to bring irrelevant matters into an argument and the study below will examine many of them. These fallacies (pathological arguments!) demonstrate the lengths to which people will go to win an argument, even if they cannot prove their point! Fallacies of relevance share a common characteristic in that the arguments in which they occur have premises that are logically irrelevant to the conclusion. Yet, the premises seem to be relevant psychologically, so that the conclusion seems to follow from the premises. The actual connection between premises and conclusion is emotional, not logical. To identify a fallacy of relevance, you must be able to distinguish between genuine evidence and various unrelated forms of appeal. FALLACIES THAT ATTACK I. Appeal to Force (Argumentum ad Baculum ="argument toward the club or stick") "Who overcomes by force has overcome but half his foe." Milton. "I can stand brute force, but brute reason is quite unbearable. There is something unfair about its use. It is like hitting below the intellect." Oscar Wilde 1 NB: This material is taken from several logic texts authored by N. -

Appendix 1 a Great Big List of Fallacies

Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense Appendix 1 A Great Big List of Fallacies To avoid falling for the "Intrinsic Value of Senseless Hard Work Fallacy" (see also "Reinventing the Wheel"), I began with Wikipedia's helpful divisions, list, and descriptions as a base (since Wikipedia articles aren't subject to copyright restrictions), but felt free to add new fallacies, and tweak a bit here and there if I felt further explanation was needed. If you don't understand a fallacy from the brief description below, consider Googling the name of the fallacy, or finding an article dedicated to the fallacy in Wikipedia. Consider the list representative rather than exhaustive. Informal fallacies These arguments are fallacious for reasons other than their structure or form (formal = the "form" of the argument). Thus, informal fallacies typically require an examination of the argument's content. • Argument from (personal) incredulity (aka - divine fallacy, appeal to common sense) – I cannot imagine how this could be true, therefore it must be false. • Argument from repetition (argumentum ad nauseam) – signifies that it has been discussed so extensively that nobody cares to discuss it anymore. • Argument from silence (argumentum e silentio) – the conclusion is based on the absence of evidence, rather than the existence of evidence. • Argument to moderation (false compromise, middle ground, fallacy of the mean, argumentum ad temperantiam) – assuming that the compromise between two positions is always correct. • Argumentum verbosium – See proof by verbosity, below. • (Shifting the) burden of proof (see – onus probandi) – I need not prove my claim, you must prove it is false. • Circular reasoning (circulus in demonstrando) – when the reasoner begins with (or assumes) what he or she is trying to end up with; sometimes called assuming the conclusion. -

Adorbs Quizzes.Indd

Name: ____________________________ ____ / 10 points THE AMAZING DOCTOR RANSOM’S Q UIZ 1 for adorable fallacies 1–7 COMPREHENSION Answer the following big-picture questions, demonstrating your grasp of the material along with some origi- nal thought. (2 pts each) 1. Define Ad Hominem. Is the truth of a proposition affected by the character of the speaker? 2. If you’re writing a paper (or reading one), list at least five criteria that can help you deter- mine whether an authority is relevant or not? IDENTIFICATION Identify the adorable fallacy present, or declare the reasoning fallacy-free. (1 pt each) 3. Gillette: “If there’s a lumberjack with a manly jaw using our brand of razor, it must work.” 4. Shark: “You lions disgust me. Preying on the weak of the Serengeti is a grievous wrong.” Lion: “What’s the big deal? You do it too.” 5. Friend: “You can’t tell me I shouldn’t watch this when you’re such a pious dweeb.” Quizzes and tests copyright © 2015 by Canon Press. You may make as many copies as you need. CONT. 6. Son: “I can’t believe you won’t let me buy a Harley-Davidson motorcycle, Mom. It’s because you’re a woman, isn’t it?” 7. Presbyterian: “Our children shouldn’t read The Lord of the Rings because, after all, Tolkien was a Roman Catholic.” 8. “Unless you apologize to me, I’ll post scurrilous reviews of all your products on the Web.” Name: ____________________________ ____ / 10 points THE AMAZING DOCTOR RANSOM’S Q UIZ 2 for adorable fallacies 8–14 COMPREHENSION Answer the following big-picture questions, demonstrating your grasp of the material along with some origi- nal thought. -

The-Romantic-Rationalist.Pdf

EDITED BY “ W E A R E F A R T O O JOHN PIPER & EASILY PLEASED.” DAVID MATHIS C. S. Lewis stands as one of the most influential Christians of the twentieth century. His commitment to the life of the mind and the life of the heart is evident in classics like the Chronicles of Narnia and Mere Christianity—books that illustrate the unbreakable connection between rigorous thought and deep affection. With contributions from Randy Alcorn, John Piper, Philip Ryken, Kevin Vanhoozer, David Mathis, and Douglas Wilson, this volume explores the man, his work, and his legacy—reveling in the truth at the heart of Lewis’s spiritual genius: God alone is the answer to our deepest longings and the source of our unending joy. “Altogether an interesting, lively, and thought-provoking read.” Michael Ward, Fellow of Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford; author, Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis “A great introduction to and reflection on a remarkable Christian!” Michael A. G. Haykin, Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary “Paints a well-rounded, sharply observed portrait that balances criticism with a deep love and appreciation for the works and witness of Lewis.” Louis Markos, Professor of English, Scholar in Residence, and Robert H. Ray Chair of Humanities, Houston Baptist University; author, Restoring Beauty: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis JOHN PIPER is founder and teacher of desiringGod.org and chancellor of Bethlehem College and Seminary. He served for 33 years as pastor at Beth- lehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis and is author of more than 50 books. -

CS Lewis and the Modern World

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of English Department of English 2009 "The tS ance of a Last Survivor": C. S. Lewis and the Modern World (Chapter One of The Rhetoric of Certitude) Gary L. Tandy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons The Rhetoric of Certitude The Rhetoric of Certitude C. S. Lewis's Nonfiction Prose GARY L. TANDY The Kent State University Press Kent, Ohio ~/tJGSC~CK Lf/\R~r~\' ~ n[~C~.r r.cE EN"TTR U.Cr:.Cl:" F G>' U!·1iV[F;~ iTY riE\'.TUiG. Oil 9713~' Frontis: C. S. Lewis at his desk. To Janet, Julia, Jackson, Used by permission of The Marion E. Wade Center, and John Garrison. Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. And for Mom, who waits to greet us in Aslan's Country. © 2009 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242 All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2008030054 ISBN 978-0-87338-973-0 Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tandy, Gary L. The rhetoric of certitude : C. S. Lewis's nonfiction prose I Gary L. Tandy. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-o-87338-973-0 (hardcover: alk. paper) oo 1. Lewis, C. S. (Clive Staples), 1898-1963-Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PR6023.E926z898 2009 823'.912-dc22 2008030054 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available. 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Introduction ix 1 "The Stance of a Last Survivor": C. -

<I>Letters to Malcolm</I> and the Trouble with Narnia: C.S. Lewis

Volume 26 Number 1 Article 5 10-15-2007 Letters to Malcolm and the Trouble with Narnia: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Their 1949 Crisis Eric Seddon Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Seddon, Eric (2007) "Letters to Malcolm and the Trouble with Narnia: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Their 1949 Crisis," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 26 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol26/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Proposes an intriguing solution to the question of Tolkien and Lewis’s estrangement in 1949: that it was Tolkien’s objections to anti-Catholic sentiments expressed in Lewis’s Letters to Malcolm and some beliefs deeply incompatible with Tolkien’s Catholicism expressed in the depiction of Aslan in the Chronicles of Narnia that initially estranged them. -

BESTIARY of ADORABLE FALLACIES Published by Canon Press P.O

THE AMAZING DR. RANSOM’S BESTIARY OF ADORABLE FALLACIES Published by Canon Press P.O. Box 8729, Moscow, Idaho 83843 800.488.2034 | www.canonpress.com Douglas Wilson and N.D. Wilson, The Amazing Dr. Ransom’s Bestiary of Adorable Fallacies: A Field Guide for Clear Thinkers Copyright © 2015 by Douglas Wilson and N.D. Wilson Illustrations copyright © 2015 by Forrest Dickison Cover design by James Engerbretson. Cover illustrations by Forrest Dickison. Interior design by James Engerbretson. Interior layout by Valerie Anne Bost. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the author, except as provided by USA copyright law. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is forthcoming. 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Dedicated to Douglas Wilson and N.D. Wilson, without whose magnificent labors I could not have done a fraction of this work. ~The Amazing Dr. Ransom THE AMAZING DR. RANSOM’S BESTIARY OF ADORABLE FALLACIES A FIELD GUIDE FOR CLEAR THINKERS by DOUGLAS WILSON and N.D. WILSON proxies for THE AMAZING DR. RANSOM Illustrations by FORREST DICKISON contents Foreword: The Perils Of Informal Fallacies .....................................xi Dr. Ransom’s Autobiography ..........................................................xv KINGDOM I: FALLACIES OF DISTRACTION Fallacy #1: Ad Hominem .................................................................3 -

Calvin Theological Seminary the Mythos of Sin: C. S. Lewis

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE MYTHOS OF SIN: C. S. LEWIS, THE GENESIS FALL, AND THE MODERN MOOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JEREMY G GRINNELL GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2011 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616957-8621 [email protected] www.calvinseminary.edu This dissertation entitled THE MYTHOS OF SIN: C.S. LEWIS, THE GENESIS FALL, AND THE MODERN MOOD written by JEREMY G. GRINNELL and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: .i:»: Cornelius Plantinga, Jr., Ph.D. Ron~~ Calvin P. Van Reken, Ph.D. {il!;\ Alan JacobS~ David M. Rylaarsda ,Ph.D. Date Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Copyright © 2011 by Jeremy G Grinnell All rights reserved To, for, and mostly because of Denise Could God Himself create such lovely things as I have dreamed? Answers Hope, “Whence then came thy dream?” —George MacDonald, Lilith CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 The Nature of the Project ............................................................................ 4 Method of the Exploration -

List of Fallacies

List of fallacies For specific popular misconceptions, see List of common if>). The following fallacies involve inferences whose misconceptions. correctness is not guaranteed by the behavior of those log- ical connectives, and hence, which are not logically guar- A fallacy is an incorrect argument in logic and rhetoric anteed to yield true conclusions. Types of propositional fallacies: which undermines an argument’s logical validity or more generally an argument’s logical soundness. Fallacies are either formal fallacies or informal fallacies. • Affirming a disjunct – concluding that one disjunct of a logical disjunction must be false because the These are commonly used styles of argument in convinc- other disjunct is true; A or B; A, therefore not B.[8] ing people, where the focus is on communication and re- sults rather than the correctness of the logic, and may be • Affirming the consequent – the antecedent in an in- used whether the point being advanced is correct or not. dicative conditional is claimed to be true because the consequent is true; if A, then B; B, therefore A.[8] 1 Formal fallacies • Denying the antecedent – the consequent in an indicative conditional is claimed to be false because the antecedent is false; if A, then B; not A, therefore Main article: Formal fallacy not B.[8] A formal fallacy is an error in logic that can be seen in the argument’s form.[1] All formal fallacies are specific types 1.2 Quantification fallacies of non sequiturs. A quantification fallacy is an error in logic where the • Appeal to probability – is a statement that takes quantifiers of the premises are in contradiction to the something for granted because it would probably be quantifier of the conclusion. -

Logic I and II

Logic I and II PEIMS Code: N1290100, N1290101 Abbreviation: LOGIC1, LOGIC2 Grade Level(s): 9–10 Award of Credit: 0.5 each course Approved Innovative Course • Districts must have local board approval to implement innovative courses. • In accordance with Texas Administrative Code (TAC) §74.27, school districts must provide instruction in all essential knowledge and skills identified in this innovative course. • Innovative courses may only satisfy elective credit toward graduation requirements. • Please refer to TAC §74.13 for guidance on endorsements. Course Description: Logic I provides course content in informal logic which includes intensive experience with logical fallacies and an emphasis on inductive reasoning, strong versus weak and fallacious arguments, and probability. Informal logic concentrates on evaluating the content of an argument and deals almost entirely with “ordinary language arguments” in the interchange of ideas between people. Logic II is a course in formal logic, or the logic that pertains to pure reasoning in the abstract – deductive reasoning, valid or invalid arguments, and certainty (given the premise). In Logic II, students fully engage in the world of syllogism where focus is placed on understanding the form of an argument, and arguments can be analyzed using symbols. Essential Knowledge and Skills: Logic I (a) General Requirements. This course is recommended for students in grades 9 and 10. Students shall be awarded one-half credit for successful completion of this course. (b) Introduction. (1) Logic I complements thinking, writing, and speaking skill-building that is at the center of language arts and social studies curricula. Logic also complements Latin knowledge; it aims at precision of language and Latin is a very precise language, and many of the names of logical fallacies are derived from Latin. -

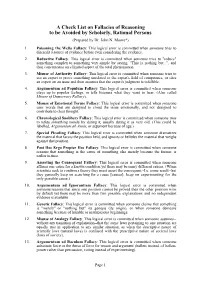

A Check List on Fallacies of Reasoning to Be Avoided by Scholarly, Rational Persons (Prepared by Dr

A Check List on Fallacies of Reasoning to be Avoided by Scholarly, Rational Persons (Prepared by Dr. John N. Moore*) 1 Poisoning the Wells Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone tries to discredit a source of evidence before even considering the evidence. 2. Reductive Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone tries to "reduce" something complex to something very simple by saying, "This is nothing but...", and then concentrates on a limited aspect of the total phenomenon. 3. Misuse of Authority Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone tries to use an expert to prove something unrelated to the expert's field of competence, or cites an expert on an issue and then assumes that the expert's judgment is infallible. 4. Argumentum ad Populum Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone plays up to popular feelings, or tells listeners what they want to hear. (Also called Misuse of Democracy Fallacy). 5. Misuse of Emotional Terms Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone uses words that are designed to cloud the issue emotionally, and not designed to contribute to clear thought. 6. Chronological Snobbery Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone tries to refute something merely by dating it, usually dating it as very old. (This could be labelled, Argumentum ab Annis, or argument because of age.) 7. Special Pleading Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone dramatizes the material that favors the position held, and ignores or belittles the material that weighs against that position. 8. Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc Fallacy: This logical error is committed when someone reasons that something is the cause of something else merely because the former is earlier in time.