Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of Yugoslavia's People's Republic of Macedonia 377 Ward the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party Hardened

THE MAKING OF YUGOSLAVIA’S PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Fifty years since the liberation of Macedonia, the perennial "Ma cedonian Question” appears to remain alive. While in Greece it has deF initely been settled, the establishment of a "Macedonian State” within the framework of the People’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has given a new form to the old controversy which has long divided the three Balkan States, particularly Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. The present study tries to recount the events which led to its founding, the purposes which prompted its establishment and the methods employed in bringing about the tasks for which it was conceived. The region of Southern Yugoslavia,' which extends south of a line traversed by the Shar Mountains and the hills just north of Skopje, has been known in the past under a variety of names, each one clearly denoting the owner and his policy concerning the region.3 The Turks considered it an integral part of their Ottoman Empire; the Serbs, who succeeded them, promptly incorporated it into their Kingdom of Serbs and Croats and viewed it as a purely Serbian land; the Bulgarians, who seized it during the Nazi occupation of the Balkans, grasped the long-sought opportunity to extend their administrative control and labeled it part of the Bulgarian Father- land. As of 1944, the region, which reverted to Yugoslavia, has been known as the People’s Republic of Macedonia, one of the six federative republics of communist Yugoslavia. The new name and administrative structure, exactly as the previous ones, was intended for the purpose of serving the aims of the new re gime. -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

Amendment to Registration Statement

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 08/14/2020 3:22:34 PM OMB No. 1124-0003; Expires July 31, 2023 U.S. Department of Justice Amendment to Registration Statement Washington, dc 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended INSTRUCTIONS. File this amendment form for any changes to a registration. Compliance is accomplished by filing an electronic amendment to registration statement and uploading any supporting documents at https://www.fara.gov. Privacy Act Statement. The filing of this document is required for the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq., for the purposes of registration under the Act and public disclosure. Provision of the information requested is mandatory, and failure to provide the information is subject to the penalty and enforcement provisions established in Section 8 of the Act. Every registration statement, short form registration statement, supplemental statement, exhibit, amendment, copy of informational materials or other document or information filed with the Attorney General under this Act is a public record open to public examination, inspection and copying during the posted business hours of the FARA Unit in Washington, DC. Statements are also available online at the FARA Unit’s webpage: https://www.fara.gov. One copy of eveiy such document, other than informational materials, is automatically provided to the Secretary of State pursuant to Section 6(b) of the Act, and copies of any and all documents are routinely made available to other agencies, departments and Congress pursuant to Section 6(c) of the Act. The Attorney General also transmits a semi-annual report to Congress on the administration of the Act which lists the names of all agents registered under the Act and the foreign principals they represent. -

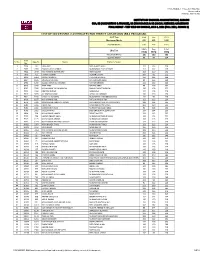

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Dimitris Christopoulos Kostis Karpozilos

Dimitris Christopoulos Kostis Karpozilos 10+1 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS on the MACEDONIAN QUESTION 10+ 1 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS ON THE MACEDONIAN QUESTION 10+1 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS on the MACEDONIAN QUESTION DIMITRIS CHRISTOPOULOS KOSTIS KARPOZILOS ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG OFFICE IN GREECE To all those Greek women and men who spoke out regarding the Macedonian Question in a documented and critical way in the decisive decade of the 1990s. For the women and men who stood up as citizens. CONTENTS Introduction to the English-language edition: The suspended step of the Prespa Agreement . 11 Introduction to the Greek-language edition: To get the conversation going . 19 1 . “ But isn’t the name of our neighbouring country a ‘national matter’ for Greece?” . 25 2 . “ Macedonia has been Greek since antiquity . How can some people appropriate all that history today?” . 31 3 . “ Isn’t there only one Macedonia and isn’t it Greek?” . 37 4 . “ But is there a Macedonian nation? Isn’t it nonexistent?” 41 5 . “ Okay, it’s not nonexistent . But it is artificial . Didn’t Tito create it?” . 49 6 . “ What is the relationship between the Greek left and the Macedonian question?” . 53 7 . “ Is there a Macedonian language?” . 59 8 . “ Are we placing Greece on the same level as a statelet, the statelet of Skopje?” . 65 9 . “ Their constitution is irredentist . Shouldn’t it be changed if we want to reach a compromise?” . 69 10 . “ So is it wrong to refer to that state as Skopje and its citizens as Skopjans?” . 77 10 + 1 . “So, is Greece not right?” . 83 Why did all this happen and what can be done about it today? . -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards - 14Th August, 2020

F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14TH AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following ‘Pakistan Civil Awards’ on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2021:- S. No. Name of Awardee Field 1 2 3 I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-QUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA’AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 20 Mr. -

Macedonia External Relations Briefing

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 6, No. 4 (MK) April 2018 Macedonia External Relations briefing: Macedonia’s Foreign Policy in 2018 Anastas Vangeli 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu Past and Present Attempts to Solve the Name Dispute Between Macedonia and Greece Introduction The key reason for the emergence of the asymmetrical name dispute is the fact that Greece treats the existence of Macedonia (a state that uses the name Macedonia and develops the concept of a non-Greek Macedonian nation, ethnicity, language, and culture) as a threat. Taking as pretext the turbulent history of the 20th century, Greece’s major objection has been that the Macedonian state is founded on a notion of irredentism. Therefore, Greece has used its leverage on the international stage, as a member of the EU, NATO and in general an established diplomatic tradition to make a change of the name of Macedonia a precondition for joining international organizations. The two parties have negotiated a possible solution under the auspices of the United Nations for almost quarter of a century. In the process they have come up with various solutions, both in terms of the legal circumstances, and the actual content of the name. In this brief, we analyze the various debates and the emergence of positions on the name issue, as well as some of the solutions that have been proposed throughout the years. Greece’s Position and Demands Starting from the premise that any usage of the term “Macedonia” to describe a non-Greek political entity is a threat towards Greece, the maximalist Greek position is that the new name of Macedonia should not contain the word “Macedonia” at all. -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49 -

North Macedonia: 'New' Country Facing Old Problems

North Macedonia: ‘New’ country facing old problems A research on the name change of the Republic of North Macedonia Willem Posthumus – s4606027 Master Thesis Human Geography - Conflicts, Territories and Identities Nijmegen School of Management Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor Henk van Houtum October 2019 36.989 words Once, from eastern ocean to western ocean, the land stretched away without names. Nameless headlands split the surf; nameless lakes reflected nameless mountains; and nameless rivers flowed through nameless valleys into nameless bays. G. R. Stewart, 1945, p. 3 2 I Preface After a bit more than a year, I can hereby present my master’s thesis. It’s about a name. Around 100 pages about a name: I could not have thought it would be such an extensive topic. Last year I had heard about Macedonia, or the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, as it was often called. I didn’t know it that well, just that it used to be part of Yugoslavia, obviously. An item in the news, however, triggered my interest: the country was about to change its name to North Macedonia. ‘Why?’ I thought. I didn’t know about the name dispute, but the more I read about it, the more I wanted to know. When I had to choose a subject for my master’s thesis, I knew I would look at this name change. A year later, I think I understand the name change and the dispute better. Still, the topic is more complicated than I thought. Understanding everything there is about it would probably take a lot more time. -

Tere Bin Laden”: ‘Islamic Terror’ Revised

JITENDER GILL “Tere bin Laden”: ‘isLamic Terror’ revised September 14th, 2001, Jinnah International Airport, Karachi, Pakistan— an inept TV reporter, clutching his flying toupee, declares that all passengers in the first flight taking off from Karachi, Pakistan, to the USA after World Trade Center bombings are Americans, except one, who rushes to the screen with a parodic message, “I love Amreeka,” inscribed on his bag. With repeated announcements about stringent restrictions on carry on items in the background, Ali Hassan, the Pakistani passenger, waits in line to use the toilet as a local man struggles to disentangle the tie of his pajama. As Ali offers him a discarded pair of scissors to cut the knot, the man remarks to an outraged Ali, “Taxi driver ban ne ja rahe ho (So, you are going to America to become a taxi driver)!” This scene from Tere Bin Laden is a telling commentary on the plight of citizens all over the world who struggle to disentangle the knotty problems created by terrorists while governments indulge in political 140 skullduggery. Ali getting a pair of scissors to cut this knot anticipates the climax of the film, where the protagonist fortuitously provides a comic resolution to the confusion of terrorist violence and political one-upmanship between megalomaniacs belonging to different countries. Tere Bin Laden, a Hindi film released in 2010, turned out to be a surprise box office success despite lacking top-notch film stars, melodrama, and the song-and-dance routines of a typical Bollywood film. The film projects a dystopic vision of an Islamic society that is adrift in violence that has become endemic to its culture.1 In a socio-political milieu where religious fanatics openly collaborate with a corrupt ruling class, an ambitious journalist desirous of immigrating to America is advised that the “best bet” or “foolproof ” path “TERE BIN LADEN”: ‘ISLAMIC REVISED TERROR’ to reach this hated Islamic enemy-cum-land of dreams is to pretend to be a mujahideen2 and surrender to the American army in Iraq. -

Conferment of Awards

CONFIDENTIAL (NOT TO BE PUBLISHED/TRANSMITTED AND TELECASTED BEFORE 14.08.2020) F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14Th AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following 'Pakistan Civil Awards' on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23m March, 2021:- iiaL I. NISHAN-1-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-OUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA'AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunlchwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Palchttullthwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 20 Mr. -

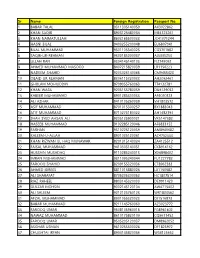

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No. 1 BABAR

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No.