Tere Bin Laden”: ‘Islamic Terror’ Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

AMENDED COMPLAINT ) CAMILLE DOYLE, in Her Own Right As the ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Mother of JOSEPH M

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA THOMAS E. BURNETT, SR., in his own right as ) the Father of THOMAS E. BURNETT, JR., ) CIVIL ACTION Deceased ) ) Case Number 1:02CV01616 BEVERLY BURNETT, in her own right as the ) Mother of THOMAS E. BURNETT, JR., ) Deceased ) ) DEENA BURNETT, in her own right and as ) Representative of the ESTATE OF THOMAS E. ) BURNETT, JR., Deceased ) ) MARY MARGARET BURNETT, in her own ) right as the Sister of THOMAS E. BURNETT, ) JR., Deceased ) ) MARTHA BURNETT O’BRIEN, in her own right ) as the Sister of THOMAS E. BURNETT, JR., ) Deceased ) ) WILLIAM DOYLE, SR., in his own right as the ) Father of JOSEPH M. DOYLE, Deceased ) AMENDED COMPLAINT ) CAMILLE DOYLE, in her own right as the ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Mother of JOSEPH M. DOYLE, Deceased ) ) WILLIAM DOYLE, JR., in his own right as the ) Brother of JOSEPH M. DOYLE, Deceased ) ) DOREEN LUTTER, in her own right as the Sister ) of JOSEPH M. DOYLE, Deceased ) ) DR. STEPHEN ALDERMAN, in his own right ) and as Co-Representative of the ESTATE OF ) PETER CRAIG ALDERMAN, Deceased ) ) ELIZABETH ALDERMAN, in her own right and ) as Co-Representative of the ESTATE OF PETER ) CRAIG ALDERMAN, Deceased ) ) JANE ALDERMAN, in her own right as the Sister ) of PETER CRAIG ALDERMAN, Deceased ) ) YVONNE V. ABDOOL, in her own right as an ) Injured Party ) ALFRED ACQUAVIVA, in his own right as the ) Father of PAUL ANDREW ACQUAVIVA, ) Deceased ) ) JOSEPHINE ACQUAVIVA, in her own right as ) the Mother of PAUL ANDREW ACQUAVIVA, ) Deceased ) ) KARA HADFIELD, -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Location, Event&Q

# from what/ where which how why who for MOBILE versi on click here when who who where when index source "location, event" "phys, pol, med, doc" detail physical detail political name "9/11 Truth Interactive Spreadsheet Click on dow n arrow to sort / filter, click again to undo." Top 100 / compilations entity entity detail country / state date Item .. right-click on li nk to open in new tab 1 "Francis, Stephen NFU" WTC physical Controlled demolition Explosive experts "Overwhelming evidence indicates that a combination of n uclear, thermitic and conventional explosives were used in a controlled demoliti on of the WTC on 9/11. Nanothermite contributed but does not have sufficient det onation velocity to pulverize the WTC into dust. Architects & Engineers for 9/11 Truth is leading gatekeeper trying to deflect Israel's role. See Cozen O'Connor 9/11 lawsuit." pic "9/11 Truth, anti-Zionists" Engineers / Scie ntists "U.S., Israel, SA, Britain" 2 "Francis, Stephen NFU" "WTC, Pentagon, PA" political False flag Cabal "The cabal: U.S., Britain, Saudi Arabia and Israel execu ted the 9/11 false flag attack in order to usher in a new 'war on terror' along with the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and fullfil the PNAC's 'Full Spectrum Dominan ce' of the Middle East and its resources ... all have roots that go back to Zion ist / Nazi Germany, the Cold War ... 9/11 was a planned step." lnk Intel ag encies "Cabal: US, UK, Israel & SA" Mossad / Sayeret Matkal "U.S., Israel, S A, Britain" 3 "Fox, Donald" WTC 1-2 physical "Mini Neutron, Fissionless Fusio n" Controlled demolition "VeteransToday: Fox, Kuehn, Prager, Vike n,Ward, Cimono & Fetzer on mini neutron bombs discuss all major WTC theories micr o nuke (neutron) most promising comparatively low blast effects, a quick blast o f radiation that doesn't linger, a series of shape charged mini-neutron bombs we re detonated from top to bottom to simulate a free fall collapse. -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards - 14Th August, 2020

F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14TH AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following ‘Pakistan Civil Awards’ on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2021:- S. No. Name of Awardee Field 1 2 3 I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-QUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA’AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 20 Mr. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Case: 11-3490 Document: 145 Page: 1 04/16/2013 908530 32 11-3294-cv(L), et al. In re Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001 (Asat Trust Reg., et al.) UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2012 (Argued On: December 4, 2012 Decided: April 16, 2013) Docket Nos. 11-3294-cv(L), 11-3407-cv, 11-3490-cv, 11-3494-cv, 11-3495-cv, 11-3496-cv, 11-3500-cv, 11-3501- cv, 11-3502-cv, 11-3503-cv, 11-3505-cv, 11-3506-cv, 11-3507-cv, 11-3508-cv, 11-3509-cv, 11-3510- cv, 11-3511-cv, 12-949-cv, 12-1457-cv, 12-1458-cv, 12-1459-cv. _______________________________________________________________ IN RE TERRORIST ATTACKS ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 (ASAT TRUST REG., et al.) JOHN PATRICK O’NEILL, JR., et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. ASAT TRUST REG., AL SHAMAL ISLAMIC BANK, also known as SHAMEL BANK also known as BANK EL SHAMAR, SCHREIBER & ZINDEL, FRANK ZINDEL, ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, SR., ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, JR., MARTIN WATCHER, ERWIN WATCHER, SERCOR TREUHAND ANSTALT, YASSIN ABDULLAH AL KADI, KHALED BIN MAHFOUZ, NATIONAL COMMERCIAL BANK, FAISAL ISLAMIC BANK, SULAIMAN AL-ALI, AQEEL AL-AQEEL, SOLIMAN H.S. AL-BUTHE, ABDULLAH BIN LADEN, ABDULRAHMAN BIN MAHFOUZ, SULAIMAN BIN ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, SALEH ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH SALAIMAN AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH OMAR NASEEF, TADAMON ISLAMIC BANK, ABDULLAH MUHSEN AL TURKI, ADNAN BASHA, MOHAMAD JAMAL KHALIFA, BAKR M. BIN LADEN, TAREK M. BIN LADEN, OMAR M. BIN LADEN, DALLAH AVCO TRANS ARABIA CO. LTD., DMI ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES S.A., ABDULLAH BIN SALEH AL OBAID, ABDUL RAHMAN AL SWAILEM, SALEH AL-HUSSAYEN, YESLAM M. -

THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION of OSAMA BIN LADEN by Copyright 2008 Christopher R. Carey Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program In

THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION OF OSAMA BIN LADEN BY Copyright 2008 Christopher R. Carey Submitted to the graduate degree program in International Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. ___Dr. Rose Greaves __________________ Chairperson _Dr. Alice Butler-Smith ______________ Committee Member _ Dr. Hal Wert ___________________ Committee Member Date defended:___May 23, 2008 _________ Acceptance Page The Thesis Committee for Christopher R. Carey certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: THE IDEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION OF OSAMA BIN LADEN _ Dr. Rose Greaves __________ Chairperson _ _May 23, 2008 ____________ Date approved: 2 Abstract Christopher R. Carey M.A. International Studies Department of International Studies, Summer 2008 University of Kansas One name is above all others when examining modern Islamic fundamentalism – Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden has earned global notoriety because of his role in the September 11 th attacks against the United States of America. Yet, Osama does not represent the beginning, nor the end of Muslim radicals. He is only one link in a chain of radical thought. Bin Laden’s unorthodox actions and words will leave a legacy, but what factors influenced him? This thesis provides insight into understanding the ideological foundation of Osama bin Laden. It incorporates primary documents from those individuals responsible for indoctrinating the Saudi millionaire, particularly Abdullah Azzam and Ayman al-Zawahiri. Additionally, it identifies key historic figures and events that transformed bin Laden from a modest, shy conservative into a Muslim extremist. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not be possible without inspiration from each of my committee members. -

Conferment of Awards

CONFIDENTIAL (NOT TO BE PUBLISHED/TRANSMITTED AND TELECASTED BEFORE 14.08.2020) F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14Th AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following 'Pakistan Civil Awards' on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23m March, 2021:- iiaL I. NISHAN-1-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-OUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA'AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunlchwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Palchttullthwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Palchtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber PalchtunIchwa) 20 Mr. -

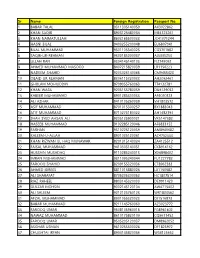

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No. 1 BABAR

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No. -

Islamabad High Court

_ _ ISLAMABAD HIGH COURT DAILY REGULAR CAUSE LIST FOR MONDAY, 27 SEPTEMBER, 2021 THE HONORABLE CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE AAMER FAROOQ NOTE: Old cases will not be adjourned except with prior adjustments and with the consent of opposite counsel. OLD CASES 1. Cust. Ref. 2/2015 (46152) Director of Intelligence and Investigation V/s SS Corporation, etc A CM 1/2015 Mujeeb-ur-Rehman Warraich CM 2/2015 MOTION CASES 1. Crl. Appeal 77/2021 Acquittal (131152) The State V/s Muhammad Israr etc A Other Advocate General NOTICE CASES 1. Part Heard (130761) Mosharraf Ali Zaidi & others V/s The President of Pakistan & others FC W.P. 1925/2021 Misc. Other FAISAL SIDDIQI Additional Attorney General, CM 2/2021 Assistant Attorney General, Attorney General for Pakistan, Deputy Attorney General, Mansoor Tariq, Ms.Kulsum Khaliq, Shahid Hamid, Sikandar Naeem Qazi W.P. 127/2021 (125274) Dr. Asfandiyar, etc V/s FOP, etc FC CM 1/2021 (Soban Ali, Adv.) In Person, Mudassar Khalid Moazzam Ali Shah, Qausain Abbasi, Arshad Abbas Faisal Mufti, Assistant Attorney General 2. Crl. Misc. 949/2021 Bail After (134907) Zahir Ullah V/s State, etc A Arrest Muhammad Shaheen By I.T. Department, Islamabad High Court Report Auto Generated By: C F M S Print Date & Time:23-SEP-2021 05:23 PM Page 1 of 87 _ _ DAILY REGULAR CAUSE LIST FOR MONDAY, 27 SEPTEMBER, 2021 THE HONORABLE CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE AAMER FAROOQ NOTICE CASES 3. Crl. Appeal 208/2020 Against (124285) Bait Ullah V/s The State etc FC Convct. -

Ardh Kumbh Mela Opens to Colourful Start in Haridwar | India | Hindustan Times

1/19/2016 Ardh Kumbh Mela opens to colourful start in Haridwar | india | Hindustan Times follow us: epaper india vs australia breathe delhi delhi nursery admissions bigg boss 9 movie reviews paathshala: you read they learn Ardh Kumbh Mela opens to colourful start in Haridwar Neha Pant, Hindustan Times, Haridwar | Updated: Jan 14, 2016 19:16 IST Devotees take a holy dip in the Ganga on the first day of Ardh Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, on Thursday. (Vinay Santosh Kumar/HT photo) Share 914 Share Share Share The Ardh Kumbh Mela opened to a colourful start in Haridwar, with thousands of devotees taking part in the first ‘snan’ or holy dip in the Ganga on the auspicious occasion of Makar Sankranti on Thursday. The Har Ki Pauri – the famous ghaat on the banks on the Ganga in Haridwar – witnessed a rush of pilgrims from across the country, with devotees immersing themselves into the icy waters of the Ganga. The Ardh Kumbh Mela takes place in Haridwar and Allahabad every six years. Attending it is considered to be highly auspicious and a dip in the holy waters of the Ganga is believed to absolve one’s sins. “We are happy to have taken the holy dip on the first day of the (Ardh) Kumbh Mela. My mother believes it will open the doors of moksha (salvation) for her,” said Tribhuwan Pandey, a bank official who had come along with his ailing mother Kesari Devi from Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh. The police and other security forces were seen manning the ghaats, with metal detectors, sniffer dogs and tear gas on standby. -

Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across the Border: the Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Winter 3-19-2018 Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry Dina Khdair DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Khdair, Dina, "Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry" (2018). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 31. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZING PAKISTANI IDENTITY ACROSS THE BORDER: THE POLITICS OF CROSSOVER STARDOM IN THE HINDI FILM INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION In 2010, Pakistani musician and actor Ali Zafar noted how “films and music are one of the greatest tools of bringing in peace and harmony between India and Pakistan. As both countries share a common passion – films and music can bridge the difference between the two.”1 In a more recent interview from May 2016, Zafar reflects on the unprecedented success of his career in India, celebrating his work in cinema as groundbreaking and forecasting a bright future for Indo-Pak collaborations in entertainment and culture.2 His optimism is signaled by a wish to reach an even larger global fan base, as he mentions his dream of working in Hollywood and joining other Indian émigré stars like Priyanka Chopra.