Proceedings Full File Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

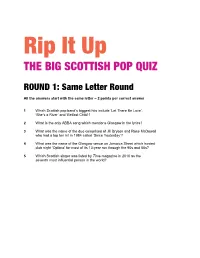

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses 5-2012 The evolution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht Recommended Citation Watkins, Madalyn, "The ve olution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities" (2012). Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses. 6. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities An Undergraduate Honors Thesis in the Crop, Soil, and Environmental Science Department Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the University of Arkansas Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences Honors Program by Madalyn Watkins April 2012 _____________________________________ _____________________________________ ____________________________________ I. Abstract The development and evolution of an agricultural system is influenced by many factors including binding constraints (limiting factors), choice of investments, and historic presence of land and income inequality. This study analyzed the development of two farming systems: mechanized, “economies of scale” farming in the Arkansas Delta and crofting in the Scottish Highlands. The study hypothesized that the current farm size in each region can be partially attributed to the binding constraints of either land or labor. -

Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Table of Contents 1 Chair’s Foreword 2 2 Fèis Facts 4 3 Key Services and Activities 5 4 Board of Directors 14 5 Staffing Report 15 6 Fèis Membership and Activities 17 7 Financial Statement 2009-10 28 Fèisean nan Gàidheal is a company limited by guarantee, registration number SC130071, registered with OSCR as a Scottish Charity, number SC002040, and gratefully acknowledges the support of its main funders Scottish Arts Council | The Highland Council | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | Highlands & Islands Enterprise Comhairle nan Eilean Siar | Argyll & Bute Council 1 Chair’s Foreword I am delighted to commend to you this year’s Annual Report From Fèisean nan Gàidheal. 2009-10 has been a challenging, and busy, year For the organisation with many highlights, notably the success oF the Fèisean themselves. In difficult economic times, Fèisean nan Gàidheal’s focus will remain on ensuring that support for the Fèisean remains at the heart of this organisation’s efforts. Gaelic drama also continued to flourish with drama Fèisean in schools, Meanbh-Chuileag’s perFormance tour of Gaelic schools and a successFul Gaelic Drama Summer School. In addition work was begun on radio drama in the Iomairtean Gàidhlig areas, continuing to make a valuable contribution to increasing the use oF Gaelic among young people. Fèisean nan Gàidheal continued to develop its use oF Gaelic language with Gaelic training to stafF, volunteers and tutors. Our service provides support to Fèisean to ensure that they produce printed and web materials bilingually, and seeks to help Fèisean ensure a greater Gaelic content in their activities. -

Folk & Roots Festival 2

Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots Festival 2014 5th October – 15th November Beacon Arts Centre, Greenock TICKETS: 01475 723723 www.beaconartscentre.co.uk FSundayAR 5thFAR October FROM YPRES FAR, FAR FROMSiobhan MillerYPRES N.B.7.30pm Because of the content of the material and the narrative, we would The music, songs and poetry of World War One from a Scottish perspective Sunday 5th October 3pm Welcome back... askMain that Theatre there is no applause until each half is finished. However, it is not to Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots a production of unremitting gloom, so if you would like to sing some of The Session Festival, brought to you courtesy of Far, Far From Ypres the choruses, please do so. Here’s some help: 1914 2014 Riverside Inverclyde. from “any village in Scotland”, telling of A free (ticketed) event at The Beacon Concessionary tickets of £10 available to his recruitment, training, journey to the Keep the Home-fires burning, When this bloody war is over Beacon Theatre, Greenock Last year’s festival saw audience ages all, subject to availability, until 4th Somme, and return to Scotland. Images This acoustic event is open to new-to- While your hearts are yearning, No more soldiering for me ranging from 8 to mid 80’s. Once again October, thereafter tickets priced at £15. from WW1 are projected onto a screen, Though your lads are far away When I get my civvy clothes on the-festival acts, subject to programme there’s something in the festival for deepening the audience’s understanding of everybody, hopefully offering community They dream of Home; Oh how happy I will be capacity, who register by Monday Ypres – a name forever embedded in the unfolding story. -

Minutes of Proceedings

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee Minutes of Proceedings Session 2008–09 The Scottish Affairs Committee The Scottish Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Scotland Office (including (i) relations with the Scottish Parliament and (ii) administration and expenditure of the office of the Advocate General for Scotland but excluding individual cases and advice given within government by the Advocate General). Membership during Session 2008–09 Mr Mohammad Sarwar MP, (Lab, Glasgow Central) (Chairman) Mr Alistair Carmichael, (Lib Dem, Orkney and Shetland) Ms Katy Clark MP, (Lab, North Ayrshire & Arran) Mr Ian Davidson MP, (Lab, Glasgow South West) Mr Jim Devine MP, (Lab, Livingston) Mr Jim McGovern MP, (Lab, Dundee West) David Mundell MP, (Con, Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale) Lindsay Roy MP, (Labour, Glenrothes) Mr Charles Walker MP, (Con, Broxbourne) Mr Ben Wallace MP, (Con, Lancaster and Wyre) Pete Wishart MP, (SNP, Perth and North Perthshire) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/scottish_affairs_committee.cfm. Committee staff The staff of the Committee during Session 2008–09 were Charlotte Littleboy (Clerk), Nerys Welfoot (Clerk), Georgina Holmes-Skelton (Second Clerk), Duma Langton (Senior Committee Assistant), James Bowman (Committee Assistant), Becky Crew (Committee Assistant), Karen Watling (Committee Assistant) and Tes Stranger (Committee Support Assistant). -

Language Dynamics in the Marketing of Gaelic Music Alison Lang & Wilson Mcleod

Gaelic culture for sale: language dynamics in the marketing of Gaelic music Alison Lang & Wilson McLeod Scottish Gaelic culture is strongly identified with its musical tradition, and Gaelic song — both recorded and performed live — has become an increasingly popular element of Scotland’s vibrant traditional music scene. At the same time, Gaelic organisations have identified Gaelic music, and Gaelic culture more generally, as a key resource for language development in Scotland. The audience (or, to put it more directly, the market) for Gaelic song thus consists not only of the Gaelic community but many English monoglots as well—a linguistic dynamic that presents significant challenges in terms of how this material is packaged and transmitted. In this paper we look at how Gaelic and English are used in presenting Gaelic music, and Gaelic culture more generally, to this audience (or these audiences). In doing so, we consider what role this cultural dynamic is playing within the conceptualisation and implementation of Gaelic development strategies. The focus here is on recorded rather than live musical performance (although interesting research could be conducted into performers’ practices with regard to language use in the context of live performance), considering the ways in which commercial recordings of Gaelic music are ‘packaged’ in linguistic terms. We began with the observation that there appears to be too much English around Gaelic music — too much English spoken where Gaelic songs are sung and too much English written where Gaelic songs are presented and explained — and that this is problematic from the standpoint of Gaelic language maintenance and development. -

CARRY on STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the Best Folk Club in the World! Dateline: Wednesday 11 November 2020 Volume 1.13

CARRY ON STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the best folk club in the world! Dateline: Wednesday 11 November 2020 Volume 1.13 Hovey when he came to Edinburgh CONTENTS CARRYING STREAM researching the original eighteenth-century Page 1 Lead story FESTIVAL – HAMISH tunes favoured by Burns, which he was to Page 2 Hot News 1 and Hot News 2 go on to arrange. Page 3 Fraser Bruce: The Folk River HENDERSON ANNUAL Hamish introduced Jean Redpath to Hovey Page 5 Scots Traditional Hall of Fame: LECTURE recommending her as the voice to record Mary MacInnes his arrangements. Thus began an unlikely Page 6-7 Scots Traditional Hall of Fame: working relationship between a classical Kevin Findlay composer and arranger from the USA with Page 7 Celtic Connections Festival 2021 a Scottish folk singer, used to singing Page 8 Blas Winter Festival 2021, unaccompanied or to her own guitar, and Turning (Byre Theatre), Winter unable to read music. Festival (Shropshire) Encouraged by Hamish, the two Page 9, 10, 11 CD Reviews exchanged cassettes across the Atlantic, as Page 10 Crossword (compiled by The Jean learned Hovey’s arrangements by ear. Bairn) By 1976, when Jean began recording the Page 11-12 Wee Bits and Pieces, complete songs of Robert Burns, Hovey Music Waves, Gigs Online had researched and arranged 324 songs for Page 12-13 Gigs Online, Cyber Print, the project but died before the project English / Welsh Folk Magazines could be completed, leaving only seven of Page 14 Reminders, Festivals, Hamish Henderson the planned 22 volumes. Crossword solutions THIS YEAR’S Edinburgh Folk Club Professor McCue illustrates her lecture annual Carrying Stream Festival (#19) is with performances of these versions of massively simplified. -

Runrig Create Celtic Magic out Crowds by Richard Burdge

News Sport Letters Features Contacts Recruitment The Courier Subscriptions Ads Online Ad Features Test Drive 31 August 2009 Latest News Get me today's Courier News Headlines United keeper rushed to hospital Weather window brings Runrig create Celtic magic out crowds By Richard Burdge Young carers to get more SCONE PALACE near Perth was the backdrop at the weekend for a support massive open-air concert by Celtic rockers Runrig. Ne’erday dookers urged to An audience of over 15,000 people, including First Minister Alex Salmond, was register treated to a stirring performance on Saturday night by the ever-popular band at what lived up to its top billing as one of the major events of the Year of the Runrig create Celtic magic Homecoming. Dall developer seeks talks From the moment the band hit the stage as darkness fell, the music, venue and with objectors kind weather combined to create a magical atmosphere. Girls brave elements in As the group launched into the opening number the audience gave a rousing name of care charity welcome to guitarist Malcolm Jones, back playing after suffering a heart attack earlier this year. Scots in mid-air scare over US The realisation that the stunning venue was something special was recognised by Runrig’s business manager Steve Cullen before the show. Makeover of museum “The band want the Scone Palace concert to be a genuine showcase of all that is supported best about Scotland,” he said. Coastal route “We have people flying in from all over the world to see Runrig play at the campaigner’s trek crowning place of the Scottish kings.” completed Among the international contingent was Lizzie Trent from San Diego in the United Extraction plan is backed States. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

History Speaks from the Soil: a Case Study of Commons Enclosure in the Clearance Era on North and South Uist

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2019 HISTORY SPEAKS FROM THE SOIL: A CASE STUDY OF COMMONS ENCLOSURE IN THE CLEARANCE ERA ON NORTH AND SOUTH UIST Anna Rachel Herrington University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0974-3260 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.264 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herrington, Anna Rachel, "HISTORY SPEAKS FROM THE SOIL: A CASE STUDY OF COMMONS ENCLOSURE IN THE CLEARANCE ERA ON NORTH AND SOUTH UIST" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--History. 55. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/55 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Gowan Hill Heritage Trail

Xpert Xplorer This leaflet is intended to help you explore Stirling Heritage Trails and enjoy Stirling as a “Walkable City”. Gowan Hill Welcome to the Gowan Hill ROUTE 1 - 0.6 miles / 1km (approx. 15 minutes at an average walking pace) Visit travelinescotland.com to help you plan your Heritage Trail Heritage Trail journey to, in and around Stirling. ROUTE 2 - 1 mile / 1.7km (approx. 25 minutes at an average walking pace) Visit walkit.com to help you plan your way around Stirling on foot. Start both routes from the interpretation board by the wall of Ballengeich Cemetery below the east side Remember to follow the Scottish Outdoor Access of Stirling Castle. Head away from the Castle over Code while exploring the Stirling Heritage Trails. the grass towards a set of steps on your right. At the top of the steps you’ll see another interpretation board. Follow the paved trail next to the board as it 1 curves down past a woodland trail on your left, then Ben Venue by David Young Cameron, © Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum curves right to an orchard. Just as the path curves left again you’ll see a grassy path on your left. Take this up to a grassy plateau where there are two more interpretation boards. From the interpretation board Interpretation Board with a view of Mote Hill, take another grassy path Litter/Dog Bin down the hill and back to the paved path. Paved Trail Mote To complete Route 1, turn right at the junction and Unpaved Trail 2 3 4 5 Hill follow the paved path back to your start point. -

Écosse Bro-Skos Scotland

ÉCOSSE BRO-SKOS SCOTLAND Showcasing Scotland at Festival Interceltique de Lorient ALBA The Pavilion of Honour Thank you to all our generous sponsors for their kind support at this year’s Festival Interceltique de Lorient. Partners – 2 CONTENTS WELCOME | FÀILTE 4 SHOWCASING SCOTLAND AT FESTIVAL 7 INTERCELTIQUE DE LORIENT DON’T MISS 18 SCOTLAND PAVILION PROGRAMME 25 COMPETITION 29 PARTNERS 31 – 3 WELCOME | FÀILTE | BIENVENUE | DEGEMER MAT Welcome to Scotland in Lorient! We are delighted to be the Country of Honour at this year’s Festival Interceltique de Lorient. Scotland’s folk, traditional and Gaelic music scenes have arguably never been stronger, and we are delighted to present a packed ten-day programme – across the festival, and in the Scotland Pavilion – featuring legendary, renowned artists alongside some of the most groundbreaking talent taking our music in exciting new directions. It’s often said that a country’s music is shaped by its landscape, and so we urge you to discover more about just that, and stop by the VisitScotland and HebCelt stands to explore the huge array of destinations, festivals and vacation possibilities that Scotland has to offer. Scotland is a country also renowned for its food and drink, and we’re pleased to be able to offer a selection of our finest produce at the festival as well. As with visiting Scotland itself, we promise everyone a very warm welcome, and look forward to seeing you over the festival at the Scotland Pavilion. Slàinte! Merci! Yec’head mat! #LorientFestival17 festival-interceltique.bzh/le-pays-invite – 4 ‘Over 200 of Scotland’s finest musicians are performing at this year’s festival – representing emerging young talent and firmly established acts – and are sure to delight existing fans and create new ones.