The Story of Rum National Nature Reserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

The Paleolithic and Mesolithic Occupation of the Isle of Jura, Argyll

John MERCER, Edinburgh THE PALAEOLITHIC AND MESOLITHIC OCCUPATION OF THE ISLE OF JURA, ARGYLL, SCOTLAND The occupation sequence about to be described has been built up from a dozen sites concentrated in N-Jura (Mercer, 1968-79).It is based on local land-sea relationships, site stratification, pollen analysis, drifted-pumice dating and radiocarbon assay.The paper 1 will begin with a discussion of the inter-linked shorelines and climate, then give an impression of the main sites and, finally, describe and compare the stone implement typology. Late Glacial habitat 2017 Jura is a vast island (fig.1) some 80 km (50 m) long.It rises to about 780 m (2500ft) Biblioteca, in the south and 470 m (1500 ft)in the north. Several recent papers have shown that W-Scotland was suitable for human habita ULPGC. tion from 11,000 or 10,500 BC. Kirk and Godwin (1963) described an organic level por at Loch Drama (Ross and Cromarty) which, with a C14 date of 12,810 ± 155 be (Q-457), had not since been overlaid by ice, although in a through valley.Kirk com realizada mented: "In view of its location on the exposed, north-west Atlantic rim of Scotland one would except ...an onset of milder oceanic conditions at an earlier date than localities in the English Lowlands or the North European Plain." He concluded his Digitalización contribution: " ... it would appear that in Northern Scotland the process of degla ciation was not unlike that established for Scandinavia, namely an early and rapid autores. los melt of the ice in western fjords and a longer survival in uplands east of the Atlantic watershed.The significance of such a possibility for plant, animal and human coloni sation needs no stressing." documento, Del Coope (summarised in Pennington, 1974), working on beetle remains, noted that © early in Zone I (12,380-10,000 BC) there was a rapid rise in temperature, from less than 10° C as a July average to almost 17° C, though winters may have remained cold. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

The Scottish Isles – Whisky & Wildlife from the Hebrides to the Shetlands (Spitsbergen)

Focusing on the aspects the Scottish isles are famous for – THE SCOTTISH ISLES – WHISKY & WILDLIFE varied wildlife and superb distinctive whiskies, this cruise takes full advantage of the outer isles in May. We delve first into the FROM THE HEBRIDES TO THE SHETLANDS ‘whisky isle’ of Islay with its eight working distilleries creating unique, peaty drams that evokes the island’s terrain. In the (SPITSBERGEN) Victorian port of Oban, the distillery produces a very different style of whisky, whilst on the Isle of Mull, in the pretty tiny fishing port of Tobermory, the distillery dates from the 18th century. Those not interested in whisky will still be spoilt for choice in terms of wildlife, from the archipelago of the Treshnish Isles to lonely and remote St Kilda. In May, both destinations will have teeming colonies of nesting seabirds such as puffins, kittiwakes and gannets. Whether from the ship’s decks, explorer boat cruising, or on foot, we may also get to see otters, seals, sea eagles, and golden eagles. We may even hear a corncrake amongst the spring orchids in the fields of the Small Isles. Other highlights include a private hosted visit to one of Scotland’s most ancient and scenic castles. As guests of clan chieftain Sir Lachlan MacLean, we will enjoy a private evening visit at his clan home that has a history running back 800 years. We will see where Christianity arrived in Scotland from Ireland, and how Harris Tweed is created in the Outer Hebrides. 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com A city of industry and elegance, Belfast is the birthplace of the Titanic, as well as being the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland. -

Recording the Manx Shearwater

RECORDING THE MANX There Kennedy and Doctor Blair, SHEARWATER Tall Alan and John stout There Min and Joan and Sammy eke Being an account of Dr. Ludwig Koch's And Knocks stood all about. adventures in the Isles of Scilly in the year of our Lord nineteen “ Rest, Ludwig, rest," the doctor said, hundred and fifty one, in the month of But Ludwig he said "NO! " June. This weather fine I dare not waste, To Annet I will go. This very night I'll records make, (If so the birds are there), Of Shearwaters* beneath the sod And also in the air." So straight to Annet's shores they sped And straight their task began As with a will they set ashore Each package and each man Then man—and woman—bent their backs And struggled up the rock To where his apparatus was Set up by Ludwig Koch. And some the heavy gear lugged up And some the line deployed, Until the arduous task was done And microphone employed. Then Ludwig to St. Agnes hied His hostess fair to greet; And others to St. Mary's went To get a bite to eat. Bold Ludwig Koch from London came, That night to Annet back they came, He travelled day and night And none dared utter word Till with his gear on Mary's Quay While Ludwig sought to test his set At last he did alight. Whereon he would record. There met him many an ardent swain Alas! A heavy dew had drenched To lend a helping hand; The cable laid with care, And after lunch they gathered round, But with a will the helpers stout A keen if motley band. -

Skye: a Landscape Fashioned by Geology

SCOTTISH NATURAL SKYE HERITAGE A LANDSCAPE FASHIONED BY GEOLOGY SKYE A LANDSCAPE FASHIONED BY GEOLOGY SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE Scottish Natural Heritage 2006 ISBN 1 85397 026 3 A CIP record is held at the British Library Acknowledgements Authors: David Stephenson, Jon Merritt, BGS Series editor: Alan McKirdy, SNH. Photography BGS 7, 8 bottom, 10 top left, 10 bottom right, 15 right, 17 top right,19 bottom right, C.H. Emeleus 12 bottom, L. Gill/SNH 4, 6 bottom, 11 bottom, 12 top left, 18, J.G. Hudson 9 top left, 9 top right, back cover P&A Macdonald 12 top right, A.A. McMillan 14 middle, 15 left, 19 bottom left, J.W.Merritt 6 top, 11 top, 16, 17 top left, 17 bottom, 17 middle, 19 top, S. Robertson 8 top, I. Sarjeant 9 bottom, D.Stephenson front cover, 5, 14 top, 14 bottom. Photographs by Photographic Unit, BGS Edinburgh may be purchased from Murchison House. Diagrams and other information on glacial and post-glacial features are reproduced from published work by C.K. Ballantyne (p18), D.I. Benn (p16), J.J. Lowe and M.J.C. Walker. Further copies of this booklet and other publications can be obtained from: The Publications Section, Cover image: Scottish Natural Heritage, Pinnacle Ridge, Sgurr Nan Gillean, Cullin; gabbro carved by glaciers. Battleby, Redgorton, Perth PH1 3EW Back page image: Tel: 01783 444177 Fax: 01783 827411 Cannonball concretions in Mid Jurassic age sandstone, Valtos. SKYE A Landscape Fashioned by Geology by David Stephenson and Jon Merritt Trotternish from the south; trap landscape due to lavas dipping gently to the west Contents 1. -

The Genetic Landscape of Scotland and the Isles

The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles Edmund Gilberta,b, Seamus O’Reillyc, Michael Merriganc, Darren McGettiganc, Veronique Vitartd, Peter K. Joshie, David W. Clarke, Harry Campbelle, Caroline Haywardd, Susan M. Ringf,g, Jean Goldingh, Stephanie Goodfellowi, Pau Navarrod, Shona M. Kerrd, Carmen Amadord, Archie Campbellj, Chris S. Haleyd,k, David J. Porteousj, Gianpiero L. Cavalleria,b,1, and James F. Wilsond,e,1,2 aSchool of Pharmacy and Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; bFutureNeuro Research Centre, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; cGenealogical Society of Ireland, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin A96 AD76, Ireland; dMedical Research Council Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, Scotland; eCentre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, Scotland; fBristol Bioresource Laboratories, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; gMedical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; hCentre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1NU, United Kingdom; iPrivate address, Isle of Man IM7 2EA, Isle of Man; jCentre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University -

Doortodoor Holidays & Short Breaks in Britain and Europe 30 NEW TOURS for 2014

Quality DoortoDoor Holidays & Short Breaks in Britain and Europe 30 NEW TOURS FOR 2014 Book With Confidence Financial Security Coach Holidays Door To Door Service Value For Money City Breaks Local Family Owned Company Personal, Friendly Service Sightseeing And Scenery Holidays By Air tel: 01298 871 222 1 www.andrews-of-tideswell.co.uk • Tel: 01298 871222 Welcome to Holidays 2014 Whether you’re looking for sightseeing, scenery, seaside or cities (or just a well-earned break!), we offer a fantastic selection of tours. Inside our latest brochure you’ll find some wonderful coach holidays and short breaks both in the UK and Europe together with holidays by air. On behalf of all Andrew’s Booking Staff and Driver/Couriers we wish you all a very happy holiday in 2014! offer a small selection of holidays by air. If you have VALuE FOr MONEy any suggestions, however small, in ways that we can Please remember that many of the items that are improve our service, or can suggest destinations you often provided at an extra cost with other tour would like us to include in future programmes please operators are included in our holiday price. Our call in or telephone to discuss them with us. tour prices are clearly laid out – most include free Your COMFOrT, SAFETy AND FiNANCiAL excursions and half board. Many tours include SECuriTy entrance fees (in some cases over £ 60.00 in value) These are of the greatest importance to us. Over The ‘Entrances included’ symbol denotes these the last two years we have invested over a million tours. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

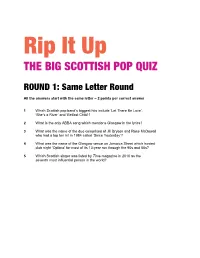

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses 5-2012 The evolution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht Recommended Citation Watkins, Madalyn, "The ve olution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities" (2012). Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses. 6. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities An Undergraduate Honors Thesis in the Crop, Soil, and Environmental Science Department Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the University of Arkansas Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences Honors Program by Madalyn Watkins April 2012 _____________________________________ _____________________________________ ____________________________________ I. Abstract The development and evolution of an agricultural system is influenced by many factors including binding constraints (limiting factors), choice of investments, and historic presence of land and income inequality. This study analyzed the development of two farming systems: mechanized, “economies of scale” farming in the Arkansas Delta and crofting in the Scottish Highlands. The study hypothesized that the current farm size in each region can be partially attributed to the binding constraints of either land or labor.