An Interview with Dr. R. Sreedhar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

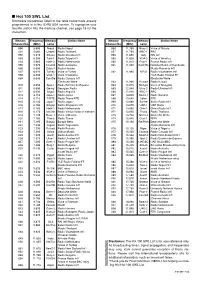

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

Digitalization of Radio Through DRM Standard on Mediumwave And

ISSN: 2277-3754 ISO 9001:2008 Certified International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT) Volume 3, Issue 9, March 2014 Digitalization of Radio through DRM Standard on Mediumwave and Shortwave Branimir Jaksic, Mile Petrovic, Petar Spalevic, Ratko Ivkovic, Sinisa Minic University of Prishtina, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia University of Prishtina, Teachers College, Leposavic, Serbia areas where analog technology AM (amplitude modulation) Abstract— this paper work offers an overview of DRM was used. It is planned that AM should be replaced with standards used in digitization of radio on medium and short waves digital technology which is similar to technologies DAB and in the world. Firstly, it provides the raw characteristics of DRM DVB-T (all of these listed technologies use OFDM technology and its working principle, with a special focus on audio coding. After that, the state of DRM transmissions in modulation) [3]. The primary purpose of DRM technology is February 2014 is given. Also it gives an summary of radio stations for transfer of the audio content. With this basic purpose, which broadcast the program using DRM technology (country DRM also supports the transfer of some multimedia content and language transmission). Broadcasting areas of radio stations with lower transmission capacity: are also provided, as well as the number of active DRM - DRM text messages; frequencies by regions of the world, for each radio station - EPG (Electronic Program Guide); separately. Then, a map of DRM transmitters in the world is - Information text services (Journaline text based shown, with their main characteristics. information service); - Transmission frames (Slideshow); Index Terms—DRM, frequencie, radio channel, transmitters. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

2020 Radio Finalists

2020 RADIO FINALISTS China National Radio New Year's Day at Home Door CNR China Radio Republik Indonesia Tears in Wuhan RRI Indonesia Japan Broadcasting Corporation The Days of Depression – A Shogi DRAMA NHK Master’s Invisible Opponent - Japan Radio Romania PEOPLE'S HOUSE ROR Romania Australian Broadcasting Corporation Punk in a pandemic ABC Australia China Radio International My Stolen Life CRI China National Radio and Television Sound Scenery-“Warming Fields” Administration NRTA DOCUDRAMA China Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting From Birth to Birth IRIB Iran China Radio International My 50 days in Wuhan CRI China Japan Broadcasting Corporation Abused Girls: Life After Abuse NHK Japan TBS Holdings, Inc. SCRATCH - Discrimination and the TBS Heisei Era - Japan DOCUMENTARY British Broadcasting Corporation Facing the bombers – two part radio BBC documentary United Kingdom 2020 RADIO FINALISTS China National Radio First in the World: China’s Coronavirus CNR Vaccine Enters Phase 2 Clinical Trial China Radio Television Hong Kong Battle Hymn of Angels in White and RTHK HongKongers-A Legend of Self-Rescue Hong Kong, China Power Radio Republik Indonesia THE FATE OF POE MEURAH RRI Indonesia Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting Scream of Butterflies IRIB NEWS REPORTING Iran The Voice of Vietnam A race for human lives VOV Vietnam National Radio and Television Together, Out of Darkness Administration NRTA China All India Radio The Zero Day Queue AIR India National Broadcasting Services of Drunk No Drive Thailand NBT ANNOUNCEMENT Thailand COMMUNITY -

A Study on the Role of Public and Private Sector Radio in Women's

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 4, Issue 2 – Pages 121-140 A Study on the Role of Public and Private Sector Radio in Women’s Development with Special Reference to India By Afreen Rikzana Abdul Rasheed Neelamalar Maraimalai† Radio plays an important role in the lives of women belonging to all sections of society, but especially for homemakers to relieve them from isolation and help them to lighten their spirit by hearing radio programs. Women today play almost every role in the Radio Industry - as Radio Jockeys, Program Executives, Sound Engineers and so on in both public and private radio broadcasting and also in community radio. All India Radio (AIR) constitutes the public radio broadcasting sector of India, and it has been serving to inform, educate and entertain the masses. In addition, the private radio stations started to emerge in India from 2001. The study focuses on private and public radio stations in Chennai, which is an important metropolitan city in India, and on how they contribute towards the development of women in society. Keywords: All India Radio, private radio station, public broadcasting, radio, women’s development Introduction Women play a vital role in the process of a nation’s change and development. The Indian Constitution provides equal status to men and women. The status of women in India has massively transformed over the past few years in terms of their access to education, politics, media, art and culture, service sectors, science and technology activities etc. (Agarwal, 2008). As a result, though Indian women have the responsibilities of maintaining their family’s welfare, they also enjoy more liberty and opportunities to chase their dreams. -

Audio Production Techniques (206) Unit 1

Audio Production Techniques (206) Unit 1 Characteristics of Audio Medium Digital audio is technology that can be used to record, store, generate, manipulate, and reproduce sound using audio signals that have been encoded in digital form. Following significant advances in digital audio technology during the 1970s, it gradually replaced analog audio technology in many areas of sound production, sound recording (tape systems were replaced with digital recording systems), sound engineering and telecommunications in the 1990s and 2000s. A microphone converts sound (a singer's voice or the sound of an instrument playing) to an analog electrical signal, then an analog-to-digital converter (ADC)—typically using pulse-code modulation—converts the analog signal into a digital signal. This digital signal can then be recorded, edited and modified using digital audio tools. When the sound engineer wishes to listen to the recording on headphones or loudspeakers (or when a consumer wishes to listen to a digital sound file of a song), a digital-to-analog converter performs the reverse process, converting a digital signal back into an analog signal, which analog circuits amplify and send to aloudspeaker. Digital audio systems may include compression, storage, processing and transmission components. Conversion to a digital format allows convenient manipulation, storage, transmission and retrieval of an audio signal. Unlike analog audio, in which making copies of a recording leads to degradation of the signal quality, when using digital audio, an infinite number of copies can be made without any degradation of signal quality. Development and expansion of radio network in India FM broadcasting began on 23 July 1977 in Chennai, then Madras, and was expanded during the 1990s, nearly 50 years after it mushroomed in the US.[1] In the mid-nineties, when India first experimented with private FM broadcasts, the small tourist destination ofGoa was the fifth place in this country of one billion where private players got FM slots. -

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI)

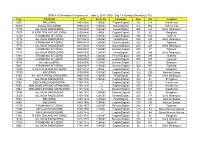

Consultation Paper No. 1/2008 Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) Consultation paper on Issues Relating to 3rd Phase of Private FM Radio Broadcasting 8th January 2008 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg New Delhi-110002 Web-site: www.trai.gov.in 1 Table of Contents Subject Page No. Preface 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 2 Background 9 Chapter 3 Regulatory and licensing issues 15 Chapter 4 Technical issues 39 Chapter 5 Other issues 57 Chapter 6 Issues for consultation 64 Annexure I International Experience 67 Annexure II Ministry of Information and 75 Broadcasting Ministry letter seeking recommendations of TRAI Annexure III List of cities with number of 77 channels that came up in phase I Annexure IV Policy of Expansion of FM radio 78 broadcast Service Annexure V List of cities where LOI was issued 104 for FM radio Broadcast under phase II Annexure VI List of cities with number of 107 channels put for re-bid under phase II Annexure VII List of suggested cities along with 110 number of channels for FM Radio phase III by BECIL Annexure VIII Proposed selection criteria by 120 Broadcast Engineering Consultants India Limited for cities in phase III Annexure IX Grant of permission agreement for 121 operating FM radio broadcast service 2 PREFACE The first phase of private sector involvement in FM radio broadcasting was launched by Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India vide its notification in year 1999. The objective behind the scheme was to attract private agencies to supplement the efforts of All India Radio by operationalising FM radio stations that provide programs of relevance with special emphasis on local content, increase content generation and improve quality of fidelity in reception. -

Broadcast Technology No.12, Autumn 2002 C NHK STRL Topics

Brazil SET2002 Congress razilian television and communications engineers, under the auspices of SET*, held their national convention in San Paulo, from BJuly 31 to August 2, 2002. In response to a invitation from the SET, Dr. Takayuki Ito from STRL gave a speech introducing NHK's latest technologies, concentrating on the research exhibited at this year's STRL Open House. At the opening of the convention, Brazil's Vice Minister of Communications, Mr. Maurico Abreu, gave an address in which he stated that a broadcasting system, capable of HDTV, SDTV, and mobile terminal services, should be selected by the end of this year. A decision on a digital terrestrial broadcasting system for Brazil is imminent. An enthusiastic discussion took place, with reports on American, European, and Japanese broadcasting systems being given by representatives from their respective countries. The SET Business forum, which was attended by approximately 300 people, also saw a lively discussion take place regarding the business aspects of Brazilian digital broadcasting. On the last day of the convention, Dr. Ito presented a report on experimental digital terrestrial broadcasting in Japan, introducing the Japanese ISDB-T system as the most technically superior of the systems under consideration. ~~ ABU Researcher Arrives at STRL ith the aim of becoming a more internationally oriented laboratory, STRL has accepted researchers from ABU (Asia-Pacific Broadcasting WUnion) participating institutions, since 2000. So far, five visiting researchers have completed their one-year research terms. As for the fiscal 2002 program, Mr. Yogendra Trihan from All India Radio arrived in July. His research is related to object-based multimedia processing. -

Freq STATION UTC Su-W-Sa Language

DRM A15 Shortwave Frequency list April 2, 2015 0300 Day 1 = Sunday (Sorted by UTC) Freq STATION UTC Su-W-Sa Language Pow Azi Location 3955 BBC(DRM) 0459-0600 1234567 English(Digital) 100 114 Woofferton 26060 Raiway Roma(DRM) 0000-2400 1234567 Italian(Digital) 0.2 ND Vatican City 11715 ALL INDIA RADIO(DRM) 0130-0230 1234567 Nepali(Digital) 250 124 Delhi (Khampur) 17675 R.NEW ZEALAND INT.(DRM) 0255-0400 .23456. English(Digital) 25 35 Rangitaiki 15220 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0300-0357 1234567 English(Digital) 300 100 Galbeni 17715 ALL INDIA RADIO(DRM) 0315-0415 1234567 Hindi(Digital) 250 245 Delhi (Khampur) 15220 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0400-0427 1234567 Chinese(digital) 250 67 Tiganesti 17715 ALL INDIA RADIO(DRM) 0415-0430 1234567 Gujarati(Digital) 250 245 Delhi (Khampur) 7390 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0430-0457 1234567 Russian(Digital) 300 37 Tiganesti 17715 ALL INDIA RADIO(DRM) 0430-0530 1234567 Hindi(Digital) 250 245 Delhi (Khampur) 7330 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0500-0527 1234567 French(Digital) 300 285 Galbeni 11800 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0530-0557 1234567 English(Digital) 300 307 Tiganesti 15785 bit eXpress(DRM) 0600-0500 1234567 German(Digital) 0.1 ND Erlangen 7435 R.ROMANIA INT.(DRM) 0600-0627 1234567 German(Digital) 300 307 Tiganesti 11690 R.NEW ZEALAND INT.(DRM) 0651-0758 .23456. English(Digital) 25 35 Rangitaiki 17790 BBC(DRM) 0759-0900 1234567 English(Digital) 100 290 Nakhon Sawan 6100 ALL INDIA RADIO (VBS)(DRM) 0900-1200 1234567 Hindi(Digital) 50 ND Delhi (Khampur) 17895 ALL INDIA RADIO(DRM) 1000-1100 1234567 English(Digital) 500 65 Bengaluru 9760 KBS WORLD RADIO(DRM) 1100-1130 ......7 English(Digital) 100 105 Woofferton 9760 NHK WORLD RADIO JAPAN(DRM) 1100-1130 .....6. -

E Global News Challenge Assessing Changes in International Broadcast News Consumption in Africa and South Asia

WORKING PAPER e Global News Challenge Assessing changes in international broadcast news consumption in Africa and South Asia. Anne Geniets November 2010 CONTENTS Executive summary Acknowledgments 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Purpose of the study ........................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Research questions ............................................................................................................ 11 1.3 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Structure of the report ...................................................................................................... 12 2 Background .............................................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................ 13 2.2 Market contexts ................................................................................................................. 13 2.3 Importance of media ......................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Media environment dynamics ......................................................................................... 20 -

Sourcebook with Marie's Help

AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009-10 EDITION WELCOME | SOURCEBOOK AIB Global WELCOME Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009 EDITION In the people-centric world of broadcasting, accurate information is one of the pillars that the industry is built on. Information on the information providers themselves – broadcasters as well as the myriad other delivery platforms – is to a certain extent available in the public domain. But it is disparate, not necessarily correct or complete, and the context is missing. The AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook fills this gap by providing an intelligent framework based on expert research. It is a tool that gets you quickly to what you are looking for. This media directory builds on the AIB's heritage of more than 16 years of close involvement in international broadcasting. As the global knowledge The Global Broadcasting MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA network on the international broadcasting Sourcebook is the Richie Ebrahim directory of T +971 4 391 4718 industry, the AIB has over the years international TV and M +971 50 849 0169 developed an extensive contacts database radio broadcasters, E [email protected] together with leading EUROPE and is regarded as a unique centre of cable, satellite, IPTV information on TV, radio and emerging and mobile operators, Emmanuel researched by AIB, the Archambeaud platforms. We are in constant contact