Areas to Explore in the Desert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Newsletter Vol.58 No

TIME SENSITIVE MATERIAL TIME SENSITIVE 84403 S Ogden, UT 4500875S E Burchard,Tom Circulation Societies FederationMineralogical of Northwest Northwest - 2913 Newsletter VOLUME 58, NO. 2 Northwest Federation of Mineralogical Societies FEB 2018 Keith Fackrell President GREETINGS Permit #7Permit McMinnville, McMinnville, OR PAID Postage U.S. Non February? It surely does not appear to be February, but looking at the Calendar it veri- - fies that it really is. Profit Org. I don’t recall any February’s being so dry and so warm for such a long time. It has been cold enough to be a little uncomfortable to do a lot of rock hunting (at least in my local area) so it is a good time to go to your rock pile and pick out some good rocks to cut and polish. It is also the time of year to pre- pare for the upcoming shows. There are many Gem & Mineral Shows on the horizon. Check the listing in your Northwest Federation of Mineralogical Societies (NFMS) Newsletter. If you are traveling beyond the boundaries of NFMS, you can check on the internet for Rock & Gem listing of many shows in any part of the United States. You can enhance your vacation and meet new friends by attending some of the shows wherever you travel. Now, I am asking for your help! I am asking for the NFMS Delegate or the President of your club/Society in the NFMS to make a list consisting of each member in your club/Society who has passed away in the last year since January 1, 2017 to the Present time, along with respective death dates. -

D.7 Cultural and Paleontological Resources

Devers–Palo Verde No. 2 Transmission Line Project D.7 CULTURAL AND PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES D.7 Cultural and Paleontological Resources D.7.1 Regional Setting and Approach to Data Collection This section discusses the cultural and paleontological resources located in the general area of the Pro- posed Project. Background information for the project area is provided (Section D.7.2 and D.7.3) along with a list of applicable regulations (Section D.7.4). Potential impacts and mitigation measures for the Proposed Project are outlined by segment in Sections D.7.6 and D.7.7. Project alternatives are addressed in Sections D.7.8 and D.7.9. A cultural resource is defined as any object or specific location of past human activity, occupation, or use, identifiable through historical documentation, inventory, or oral evidence. Cultural resources can be separated into three categories: archaeological, building and structural, and traditional resources (DSW EIR, 2005). Archaeological resources include both historic and prehistoric remains of human activity. Historic re- sources can consist of structures (cement foundations), historic objects (bottles and cans), and sites (trash deposits or scatters). Prehistoric resources can include lithic scatters, ceramic scatters, quarries, habitation sites, temporary camps/rock rings, ceremonial sites, and trails. Building and structural sites can vary from historic buildings to canals, historic roads and trails, bridges, ditches, and cemeteries. A traditional cultural resource or traditional cultural property (TCP) can include Native American sacred sites (rock art sites) and traditional resources or ethnic communities important for maintaining the cul- tural traditions of any group. Paleontology is the study of life in past geologic time based on fossil plants and animals and including phylogeny, their relationships to existing plants, animals, and environments, and the chronology of the Earth's history. -

California Vegetation Map in Support of the DRECP

CALIFORNIA VEGETATION MAP IN SUPPORT OF THE DESERT RENEWABLE ENERGY CONSERVATION PLAN (2014-2016 ADDITIONS) John Menke, Edward Reyes, Anne Hepburn, Deborah Johnson, and Janet Reyes Aerial Information Systems, Inc. Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Renewable Energy Program and the California Energy Commission Final Report May 2016 Prepared by: Primary Authors John Menke Edward Reyes Anne Hepburn Deborah Johnson Janet Reyes Report Graphics Ben Johnson Cover Page Photo Credits: Joshua Tree: John Fulton Blue Palo Verde: Ed Reyes Mojave Yucca: John Fulton Kingston Range, Pinyon: Arin Glass Aerial Information Systems, Inc. 112 First Street Redlands, CA 92373 (909) 793-9493 [email protected] in collaboration with California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program 1807 13th Street, Suite 202 Sacramento, CA 95811 and California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by: California Energy Commission US Bureau of Land Management California Wildlife Conservation Board California Department of Fish and Wildlife Personnel involved in developing the methodology and implementing this project included: Aerial Information Systems: Lisa Cotterman, Mark Fox, John Fulton, Arin Glass, Anne Hepburn, Ben Johnson, Debbie Johnson, John Menke, Lisa Morse, Mike Nelson, Ed Reyes, Janet Reyes, Patrick Yiu California Department of Fish and Wildlife: Diana Hickson, Todd Keeler‐Wolf, Anne Klein, Aicha Ougzin, Rosalie Yacoub California -

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

RMSH August 2012 Newsletter.Pdf

VOLUME 47, NO. 8 A UGUST 2012 CHALCEDONY MEETING BY D EAN S AKABE Wednesday This month’s topic is the most worked I call a stone Chalcedony, when it is sort of upon stone in any lapidary operation, translucent and homogeneous in color. August 22 Chalcedony . Chalcedony in a cryptocrys- Such as the Malawi Blue Chalcedony. 6:15-8:00 pm talline form of silica, composed of very Makiki District fine intergrowths of Quartz and Moganite. These are both silica minerals, which differ Park in the respect that quartz has a trigonal Administration crystal structure, while moganite is mono- Building clinic. Chalcedony's standard chemical structure is SiO 2 (Silicon Dioxide). Chalcedony has a waxy luster and is usu- NEXT MONTH ally semitransparent or translucent. It can Wednesday assume a wide range of colors, with the Blue Lace Agate most common seen as white to gray, blue, September 26 or brown ranging from pale to nearly Flourite black. Agates are stones which usually have col- ored layers. These are colored layers of The name "chalcedony" comes from the differently colored layers of Chalcedony. LAPIDARY calcedonius Latin , from a translation from Such as the Blue Lace Agate or Holly Blue Every Thursday khalkedon. the Greek word Unfortu- Agate. 6:30-8:30pm natelly, a connection to the town of Chal- cedon, in Asia Minor could not be found, Forms of Chalcedony are found in all 50 Second-floor Arts but one can always be hopeful. state, occurring in many colors and color and Crafts Bldg combinations. Some of the better known To make things alittle confusing is that ones are: Makiki District Chalcedony and Agate are terms used al- Park most interchangeably, as both are forms of quartz and are both Silicon Dioxide. -

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz September 10 – 13, 2005 Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum; and U.S. Geological Survey 2 Cover Photos {top left} Fortification agate, Hinsdale County, Colorado, collection of the Geology Museum, Colorado School of Mines. Coloration of alternating concentric bands is due to infiltration of Fe with groundwater into the porous chalcedony layers, leaving the impermeable chalcedony bands uncolored (white): ground water was introduced via the symmetric fractures, evidenced by darker brown hues along the orthogonal lines. Specimen about 4 inches across; photo Dan Kile. {lower left} Photomicrograph showing, in crossed-polarized light, a rhyolite thunder egg shell (lower left) a fibrous phase of silica, opal-CTLS (appearing as a layer of tan fibers bordering the rhyolite cavity wall), and spherulitic and radiating fibrous forms of chalcedony. Field of view approximately 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. {center right} Photomicrograph of the same field of view, but with a 1 λ (first-order red) waveplate inserted to illustrate the length-fast nature of the chalcedony (yellow-orange) and the length-slow character of the opal CTLS (blue). Field of view about 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. Copyright of articles and photographs is retained by authors and Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; reproduction by electronic or other means without permission is prohibited 3 Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz Program and Abstracts September 10 – 13, 2005 Editors Daniel Kile Thomas Michalski Peter Modreski Held at Green Center, Colorado School of Mines Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum U.S. -

Cultural Report

PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT Whitewater Preserve Levee Protection Project Unincorporated Riverside County, California September 11, 2020 PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT Whitewater Preserve Levee Protection Project Unincorporated Riverside County, California Prepared for: Travis J. McGill Director/Biologist ELMT Consulting 2201 North Grand Avenue #10098 Santa Ana, California 92711 Prepared by: Principal Investigator David Brunzell, M.A., RPA Contributions by Nicholas Shepetuk, B.A., and Dylan Williams, B.A. BCR Consulting LLC Claremont, California 91711 BCR Consulting LLC Project No. EMT2002 Site Recorded: Whitewater Levee Keywords: Levee USGS Quadrangles: 7.5-minute White Water, California (1988) Section 22 of Township 2 South, Range 3 East, San Bernardino Base and Meridian September 11, 2020 SEPTEMBER 11, 2020 PHASE I CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMEN T WHITEWATER PRESERVE LEVEE PROTECTION PROJECT RIVERSIDE COUNTY MANAGEMENT SUMMARY BCR Consulting LLC (BCR Consulting) is under contract to ELMT Consulting to conduct a Phase I Cultural Resources Assessment of the Whitewater Preserve Levee Protection Project (the project), consisting of 7.8 acres in unincorporated Riverside County, California. This work was completed pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) based on Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy requirements. During the current assessment, BCR Consulting completed a cultural resources records search summary, additional land use history research, and intensive field survey for the project site. The Eastern Information Center (EIC; the repository that houses cultural resources records for the project area) is closed to consultants in March 2020 due to Covid- 19 restrictions. Although the EIC has reportedly begun processing records search requests internally, we have not received results or estimated schedule for any requests since March. -

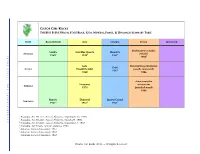

State Rocks Table.Pdf

GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Basilosaurus cetoides Marble Star Blue Quartz Hematite ALABAMA [whale] 19691 19902 19673 19844 Jade Mammuthus primigenius Gold ALASKA [Nephrite Jade] [woolly mammoth] 1967 1968 1986 STATE ROCKS STATE – Araucarioxylon Turquoise arizonicum ARIZONA 1974 [petrified wood] 1988 Bauxite Diamond Quartz Crystal ARKANSAS 19675 19676 19677 1 Alabama, Act 69-755, Acts of Alabama, September 12, 1969. 2 Alabama, Act 90-203. Acts of Alabama, March 29, 1990. GATORGIRLROCKS.COM GATORGIRLROCKS.COM 3 Alabama, Act 67-503, Acts of Alabama, September 7, 1967. 4 Alabama, Act 84-66, Acts of Alabama, 1984. 5 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 6 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 7 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. ©Gator Girl Rocks (2012) – All Rights Reserved GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Smilodon californicus Serpentine Benitoite Native Gold CALIFORNIA 8 9 10 [saber-tooth cat] 1965 1985 1965 11 1973 Stegosaurus stenops Yule Marble Aquamarine Rhodochrosite COLORADO [dinosaur] 200412 197113 200214 198215 STATE ROCKS STATE Garnet Eubrontes Giganteus – CONNECTICUT [almandine garnet] [dinosaur tracks] 197716 1991 8 California Gov. Code § 425.2. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. 1) was signed by Govenor Brown on April 20, 1965. California designated the very first official state rock with this legislation (which also created the first official state mineral). 9 California State Legislature October 1, 1985. 10 California Gov. Code § 425.1. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. -

Chapter IV. ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES

Chapter IV. ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES City of Banning General Plan WATER RESOURCES ELEMENT PURPOSE The Water Resources Element addresses water quality, availability and conservation for the City’s current and future needs. The Element also discusses the importance of on-going coordination and cooperation between the City, Banning Heights Mutual Water Company, High Valley Water District, San Gorgonio Pass Water Agency and other agencies responsible for supplying water to the region. Topics include the ground water replenishment program, consumptive demand of City residents, and wastewater management and its increasingly important role in the protection of ground water resources. The goals, policies and programs set forth in this element direct staff and other City officials in the management of this essential resource. BACKGROUND The Water Resources Element is directly related to the Land Use Element, in considering the availability of water resources to meet the land use plan; and has a direct relationship to the Flooding and Hydrology Element, in its effort to protect and enhance groundwater recharge. Water issues are also integral components of the following elements: Police and Fire Protection, Economic Development, Emergency Preparedness, and Water, Wastewater and Utilities. The Water Resources Element addresses topics set forth in California Government Code Section 65302(d). Also, in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), Section 21083.2(g), the City is empowered to require that adequate research and documentation be conducted when the potential for significant impacts to water and other important resources exists. Watersheds The westernmost part of the planning area is located at the summit of the San Gorgonio Pass, which divides two major watersheds: the San Jacinto River Watershed to the west and the Salton Sea watershed to the east. -

City of Cathedral City Comprehensive General Plan

CITY OF CATHEDRAL CITY COMPREHENSIVE GENERAL PLAN Prepared for City of Cathedral City 68-700 Avenida Lalo Guerrero Cathedral City, CA 92234 Prepared by Terra Nova Planning & Research, Inc. 400 South Farrell, Suite B-205 Palm Springs, CA 92262 Adopted July 31, 2002 Amended November 18, 2009 City of Cathedral City General Plan/Table of Contents CITY OF CATHEDRAL CITY GENERAL PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION I Introduction – amended 6/24/2009 I-1 II. ADMINISTRATION ELEMENT – amended 6/24/2009 II-1 III. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT A. Land Use Element – amended 6/24/2009 III-1 B. Circulation Element – amended 6/24/2009 III-27 C. Housing Element – adopted 11/18/2009 III-61 D. Parks and Recreation Element – amended 6/24/2009 III-121 E. Community Image and Urban Design Element – amended 6/24/2009 III-137 F. Economic and Fiscal Element – amended 6/24/2009 III-153 IV. ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES A. Biological Resources Element – amended 6/24/2009 IV-1 B. Archaeological and Historic Resources Element IV-23 C. Water Resources Element IV-38 D. Air Quality Element IV-51 E. Open Space and Conservation Element – amended 6/24/2009 IV-61 F. Energy and Mineral Resources Element – amended 6/24/2009 IV-74 V. ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS A. Geotechnical Element V-1 B. Flooding and Hydrology Element V-24 C. Noise Element – amended 6/24/2009 V-37 D. Hazardous and Toxic Materials Element V-53 VI. PUBLIC SERVICES AND FACILITIES A. Water, Sewer and Utilities Element – amended 6/24/2009 VI-1 B. -

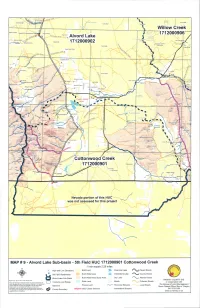

Alvord Lake Toerswnq Ihitk-Ul,.N Itj:Lnir

RtflOP' nt T37S Rt3F T37SR36E T37S R3275E 137S R34E TITStSE BloW Pour Willow Creek Babes Canyor Relds BIM Adrnirtistrative SiteFjel NeSs Airstrip / 41 171 2000906 Alvord Lake tOerswnq ihiTk-ul,.n itj:Lnir. Inokoul hluutte\ McDade Ranch 1712000902 I cvwr Twin Hot Spn Os Wilhlants Canyon , ,AEyy.4N seiralNo WARM APRI '738SR37E rIBS R3BE R38E Lower Roux Place err hlomo * / Oaterkirk Rartch - S., Rabbit HOe Mine 7,g.hit 0 Ptace '0 Arstnp 0 0 Ainord Vafley Lavy1ronrb P -o Rriaia .....c I herbbrrr RarrCh C _: 9S R34E Trout Creek CAhn '5- T39S R36E N Oleacireen Place T395 R37F Cruallu Canyon -1 Oleachea Pass T39S R38E \ Stergett Cabot Trout Creek Ranch ty Silvey Adrian Place' Wee Pole Canyon C SPRiNG, WHITEHORSE RANCH LN Pueblo Valley 4040 S Center Ridg Will, reek Pt cLean Cabin orgejadowo Gob 0810 WEIi Reynolds Ranch Owens Randr / I p labor Mocntai /1 °ueblo Mountain A'ir.STWLL Neil Pei S 'i-nWt Mahogany Ri.ge ,haaesot, uSGi, Pee: enn;s *i;i train ' 6868 4 n*a.asay Holloway T4OS R34E T4OS R35E I 1405 6E T405 R37E 'I 14'R38E / i.l:irintoi "Van Hone Basin' Colony Ranch 0 U Lithe Windy Pass z SChrERRYSPR1N. 0 I 1* RO4 - - 'r Denio Basin A' tuitdIhSPIhlNn% ()Conne eme Cottonwood Creek ie;. r' Gller Cabin T4IS R37E L,aticw P ',ik 1712000901 Grassy Basin BLAiRO tih'dlM P4 IS R34E Ago 141S R36E Lung Canyon Ii Middle Canyon Oecio Cemetery East B. ring Corral Canyon ento Nevada portion of this HUC was not assessed for this project MAP # 9 - Alvord Lake Sub-basin - 5th Field HUC 1712000901 Cottonwood Creek 1 inch equals 2.25 miles High and Low Elevations BLM Land Perennial Lake Paved Roads 5th Field Watersheds BLM Wilderness - Intermittent Lake County Roads S Alvord Lake Sub-Basin BLM Wilderness Study Area Dry Lake Arterial Roads HARNEY COUNTY GIS Prnpaeod by: Bryca Mcrnz Dare: Momlu 2006 State Land Marsh "_. -

Salton Sea Shallow Water Habitat Pilot Project

TETRA TECH, INC. 180 Howard Street, Suite 250 San Francisco, CA 94105-1617 Telephone (415) 974-1221 (510) 286-0152 FAX (415) 974-5914 August 19, 2005 Subject: Draft Environmental Assessment/Finding of No Significant Impact for the Shallow Water Habitat Pilot Project Dear Reviewer: The Bureau of Reclamation is the Lead Agency for the adoption of a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Finding of No Significant Impact for this project and is requesting comments. Please find enclosed one bound copy of the Draft Environmental Assessment/Finding of No Significant Impact. The review period is from August 22, 2005 to September 20, 2005. Please submit your written comments to: Bureau of Reclamation Lower Colorado Regional Office P.O. Box 61470 Boulder City, NV 89006-1470 Attn: Cheryl Rodriguez (LC-1340) Tel. 702.293.8167 Fax. 702.293-8023 Or if by e-mail to: [email protected] If you have any questions, please contact me at (415) 974-1221. Respectfully, Andrew Gentile Project Manager Enclosure e-mail: [email protected] world wide web: http://www.ttsfo.com This page intentionally left blank. Salton Sea Shallow Water Habitat Pilot Project Draft Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact Department of Interior Bureau of Reclamation August 2005 This page intentionally left blank. Salton Sea Shallow Water Habitat Pilot Project Draft Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact 04PE303285 by Tetra Tech, Inc. 180 Howard Street, Suite 250 San Francisco, California 94105-1617 Prepared for: U.S. Department