Mcilvaine, Stevenson.Toc.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Files, Country File Africa-Congo, Box 86, ‘An Analytical Chronology of the Congo Crisis’ Report by Department of State, 27 January 1961, 4

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/113873/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Marsh, Stephen and Culley, Tierney 2018. Anglo-American relations and crisis in The Congo. Contemporary British History 32 (3) , pp. 359-384. 10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 file Publishers page: http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 <http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 ARTICLE Congo, Anglo-American relations and the narrative of � decline: drumming to a diferent beat Steve Marsh and Tia Culley AQ2 AQ1 Cardiff University, UK� 5 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The 1960 Belgian Congo crisis is generally seen as demonstrating Congo; Anglo-American; special relationship; Anglo-American friction and British policy weakness. Macmillan’s � decision to ‘stand aside’ during UN ‘Operation Grandslam’, espe- Kennedy; Macmillan cially, is cited as a policy failure with long-term corrosive efects on 10 Anglo-American relations. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

UNITED Nations Distr

UNITED NATiONS Distr. GENERAL SECURITY S/5053/Add.12 8 October 1962 COUNCIL ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/FRENCH REPORT TO THE SECRETARY-GENERAL FROM THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN THE CONGO ON DEVELOPMENTS RELATING TO THE APPLICATION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS OF 21 FEBRUARY AND 24 NOVEMBER 1961 A. Build-Up of Katangese Mercenary Strength 1. In recent months) information has been received from various sources about a bUild-up in the strength of the Katanga armed forces) including the continued presence and some influx of foreign mercenaries. 2. It will be recalled that after the Kitona Declaration) signed on 21 December 1961 (S/5038 L Mr. Tshombe) President of the province of Katanga) made it clear to United Nations officials that he proposed to seek a solution to the mercenary problem "once and for all". This undertaking was put in writing in a letter dated 26 January 1962 to the United Nations representative in Elisabethville (S/5053/Add.3) Annex I)) and was repeated in a second letter dated 15 February 1962. 3. However) in spite of this and further declarations of Katangese spokesmen along the same lines as the above-mentioned letters) evidence ''las forthcon,ing to United. Nations authorities that in fact the pledge with regard to the elimination of mercenaries from Katanga was not being kept. 4. The ONUC-Katanga Joint Corrmissions on mercenaries) set up to certify that all foreign mercenaries had left Katanga in conformity with Mr. Tshombe's decision) visited Jadotville and Kipushi on 9 February 1962) and Kolwezi and Bunkeya on 21--23 February. -

Fallout 3 Pc Download Meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021

fallout 3 pc download meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021. Fallout 3 Crack Game Gameplay New Vegas is a game from 2021. It is considered the most popular game since its launch. With it, you can create your own character of your choice and immerse yourself in a post-apocalyptic and inspiring world. In this game, every minute you will experience a war and you need to survive. Also, the game starts from here; The Wanderer is tasked with arresting a character who was trying to escape from James. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: The latest version of Fallout 4 turned out to be obvious that the computer game is extremely famous and it just blew up all the racks. Additionally, it includes a player character known as Lonely Wanderer, who is a little boy. The fallout shelter is located in Washington, DC. The vault was sealed for 200 years until the player’s father, James, opened the door and disappeared without any information. The surrender took place on November 10, 2015 and, as shown by various information and realities, surveys of players and experts, a measure of fanart and conversations. Alternatively, you can also try Ashampoo Winoptimizer. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: Download Fallout 3 Crack Ps4 was first released on October 25, 2008 in the United States. Also, it is available on Xbox 360, PC, PS4, Ps3, and other gaming stations. Similarly, the game features realistic first- or third-person combat. The game is planned for the retro-futuristic United States between the People’s Republic of China and America. -

Questions Concerning the Situation in the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SITUATION IN THE CONGO (LEOPOLDVILLE) 57 QUESTIONS RELATING TO Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Laos, Mexico, FUTURE OF NETHERLANDS Nigeria, Panama, Somalia, Togo, Turkey, Upper NEW GUINEA (WEST IRIAN) Volta, Uruguay, Venezuela. A/4915. Letter of 7 October 1961 from Permanent Liberia did not participate in the voting. Representative of Netherlands circulating memo- A/L.371. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, randum of Netherlands delegation on future and Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory development of Netherlands New Guinea. Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, A/4944. Note verbale of 27 October 1961 from Per- Togo, Upper Volta: amendment to 9-power draft manent Mission of Indonesia circulating statement resolution, A/L.367/Rev.1. made on 24 October 1961 by Foreign Minister of A/L.368. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, Indonesia. Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory A/4954. Letter of 2 November 1961 from Permanent Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Representative of Netherlands transmitting memo- Togo, Upper Volta: draft resolution. Text, as randum on status and future of Netherlands New amended by vote on preamble, was not adopted Guinea. by Assembly, having failed to obtain required two- A/L.354 and Rev.1, Rev.1/Corr.1. Netherlands: draft thirds majority vote on 27 November, meeting resolution. 1066. The vote, by roll-call was 53 to 41, with A/4959. Statement of financial implications of Nether- 9 abstentions, as follows: lands draft resolution, A/L.354. In favour: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, A/L.367 and Add.1-4; A/L.367/Rev.1. Bolivia, Congo Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, Central African Re- (Leopoldville), Guinea, India, Liberia, Mali, public, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Nepal, Syria, United Arab Republic: draft reso- (Brazzaville), Costa Rica, Dahomey, Denmark, lution and revision. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

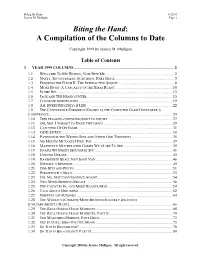

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

Sega Master System – Worthy Rival to The

C ONTENTS Vintage Contents Technology Regulars WELCOME News 3 Events 34 I am sorry to say that this will be Book review 35 the first issue which doesn’t have a print-based counterpart. We hope, Vintage Computing however, to produce the print The brave new world of videotex 8 version again in the future, but Sinclair ZX80 – first computer for under £100 12 with a lot of improvements. This Hard disks – humble, but collectible 13 will go hand in hand with enhancements to the website which Vintage Gaming will offer additional content. Sega Master System – worthy rival to the NES 14 Review of retro games for the Xbox & Playstation 16 In this issue, following on from last consoles month’s feature on teletext services, we look at 2-way videotex Vintage Calculators services. 1970s Sanyo calculators 19 The review of retro games for the Xbox/Playstation also follows on Vintage Audio, TV & Radio from the previous review of Vintage VHS video recorders – why we love them 20 modern dedicated retro game A quick look at some vintage hi-fi headphones 22 consoles. 1980s novelty radios 23 We also have the usual mix of interesting vintage subjects – from Interview headphones, VCRs to teasmades. Interview with Dave Johnson, ColecoVision games Happy collecting! designer & programmer 24 Abi Waddell – editor Miscellaneous Vintage Technology Whatever happened to the teasmade? 27 Contact: Lets party retro-tech style! 29 Exaro Publishing 67 Marksbury Repair & care Bath Transistor radio repair tips 30 BA29HP Email: Museums & collections [email protected] Nova Scotia museum, Canada 33 www.vintagetechnology.co.uk Retro game commercials and video website Nostalgia @Exaro Publishing 2008. -

ICV20 Lupant.Pub

Emblems of the State of Katanga (1960-1963) Michel Lupant On June 30 1960 the Belgian Congo became the Republic of Congo. At that time Ka- tanga had 1,654,000 inhabitants, i.e. 12.5% of the population of the Congo. On July 4 the Congolese Public Force (in fact the Army) rebelled first in Lower-Congo, then in Leopoldville. On July 8 the mutiny reached Katanga and some Europeans were killed. The leaders of the rebels were strong supporters of Patrice Lumumba. Faced with that situation on July 11 1960 at 2130 (GMT), Mr. Tschombe, Ka- tanga’s President, delivered a speech on a local radio station. He reproached the Cen- tral government with its policies, specially the recruitment of executives from commu- nist countries. Because of the threats of Katanga submitting to the reign of the arbitrary and the communist sympathies of the central government, the Katangese Government decided to proclaim the independence of Katanga.1 At that time there was no Katan- gese flag. On July 13 President Kasa Vubu and Prime Minister Lumumba tried to land at Elisabethville airport but they were refused permission to do so. Consequently, they asked United Nations to put an end to the Belgian agression. On July 14 the Security Council of the United Nations adopted a resolution asking the Belgian troops to leave the Congo, and therefore Katanga. Mr. Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General, considered the United Nations forces had to enter Katanga. Mr. Tschombe opposed that interpreta- tion and affirmed that his decision would be executed by force it need be. -

United Nations Operations in the Congo - Katanga - (Tshombe) - Cables

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 26 Date 02/06/2006 Time 12:05:34 PM S-0875-0003-07-00001 Expanded Number S-0875-0003-07-00001 items-in-Peace-keeping operations - United Nations Operations in the Congo - Katanga - (Tshombe) - cables Date Created 16/02H962 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0875-0003: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant: United Nations Operations in the Congo Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit CY 200 SSS LEO US i<5 FEB1 6 19S2 ETATPRIORITE " ' r> ,-' TO \ Or- UNATIONS j INITIALS SEGGEN FROM GARDINER 1, REFERENCE WUR i257 CONCERNING BRITISH K1ERGENARY WRENAGRE, DRAW YOUR ATTENTION TO NOTE FROM UK PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE TO SECGEN BATEB 26 JANUARY TRANSMITTED LEO BY CABLE S2S WHICH SA?S QUOTE + ACCORDING TO THE INFORMATION AVAILABLE TO THE UNITED KINGDOM GVERNMENT, WRENACRE » p g-« WAS KILLED IN SEPTEMBET IN THE COURSE OF THE FIGHTING IN KATANGA -f- UNQUOTE 2, PROPOSE THAT FATHER OF VREKACRE BE TOLD THAT OUR INFORMATION REGARDING DEATH OF HIS SON CAME FROM BRITISH GOVERNMENT WHICH SHOULD BE ASKED TO INSTRUCT CONSUL IN EVILLE TO PURSUE MATTER IN ORDER TO FURNISH a P 3/15 • MORE 'DETAILS , 3. IN MEANTIME tfE HAVE ASKED ROLZ- BENNET TO LOOK INTO THE . m~ MATTER -h n g 0-5 COL 1257 2<S H * « """* * • 0 F , ra? ON ne 1310 mm 5-39. U> ¥E ABE AWARE OF UK NOTE OF 2$ JANUARY STOP UK MISSION CQULB NOT SPECIFY SOUHCE OF INFORMATION INDICATED W &0TI BUT THOUGHT IT WAS PROBABLY G01TEHUOR NORTHEtN SHOBESIA cm mm WHOM PEECIIELY ^RENACEES FATHEB GOT HIS IWCIRHATION STOP SINCE MEJ4ACRES FATHER * ^ SONS DEATH FROK BBITISH CONSUL EUSA8ETHVILLE THROUGH BKITISH OFFICE CHA IT SEEMS POINTLESS TO ADVISE HIM SAME OF ACTION STOP PMA <2) HOPE ROL2-BENMET WILL OBTTAIN s c. -

Article Top Game Design 2020

THE TOP 50 BEST GAME DESIGN UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS 5. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF 14. UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL TECHNOLOGY FLORIDA 2019 Grads Hired: 97% Total Courses: 138 2019 Grads Salary: $64,500 Graduates: Richard Ugarte (Epic Games), Alexa Madeville (Facebook 6. UNIVERSITY OF UTAH Games), Melissa Yancey (EA). 2019 Grads Salary: $72,662 Graduates: Doug Bowser (COO, 15. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE Nintendo of America) and Nolan Faculty: Chris Perry (Pixar), Rob Bushnell (founder, Atari). Daviau (designer of Risk Legacy). 2019 Grads Hired: 60% 7. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF 2019 Grads Hired: 80% 16. CHAMPLAIN COLLEGE BECKER Fun Fact: MSU offers a west coast Total Courses: 119 1 SOUTHERN game industry field trip experience 2019 Grades Hired: 75% 2 COLLEGE each year, offering networking and CALIFORNIA learning opportunities. 17. RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE THE BEST SCHOOLS Total Courses: 230 Total Courses: 132 8. BRADLEY UNIVERSITY 2019 Grads Hired: 71% 2019 Grads Hired: 90% 2019 Grads Hired: 67% Faculty: Mark Hamer (art director, Faculty: Maurice Suckling (Driver 2019 Grads Salary: $65,000 2019 Grads Salary: $56,978 Telltale Games and Double Fine). series, Borderlands). Faculty: Marianne Krawcyzk Faculty: Jonathan Rudder (The Fun Fact: Game development teams FOR ASPIRING (writer, God of War series) Lord of the Rings Online). at Bradley are close to 50% male, 18. COGSWELL POLYTECHNIC Graduates: George Lucas Fun Fact: Becker College also 50% female. COLLEGE (creator of Star Wars) and features an esports Faculty Who Worked at Game Jenova Chen (Journey director). management program.. 9. SHAWNEE STATE UNIVERSITY Company: 96% GAME DEVELOPERS 2019 Grads Hired: 80% Faculty: Jerome Solomon (ILM, Faculty Who Worked at a Game LucasArts, EA), Stone Librande (Riot, Company: 100% Blizzard). -

For Immediate Release the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Announces Its 15Th Interactive Achievement Award Nominees

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE ACADEMY OF INTERACTIVE ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES ITS 15TH INTERACTIVE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD NOMINEES CALABASAS, Calif. – January 12, 2012 – The Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences (AIAS) today announced the finalists for the 15th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards (IAAs). More than a hundred titles were played and evaluated by members of the Academy’s Peer Panels. These panels, one for each award category, are comprised of the game industry’s most experienced and talented men and women who are experts in their chosen fields. For 2012, the blockbuster game Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception (Sony Computer Entertainment Company) leads the field with a total of twelve nominations. Showcasing the depth of great games introduced in the past year, several titles earned multiple nods for an IAA, including ten nominations for Portal 2 (Valve Corporation), nine nominations for L.A. Noire (Rockstar Games), and six nominations each for Batman: Arkham City (Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment), Battlefield 3 (Electronic Arts) and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (Bethesda Softworks). The awards ceremony will take place on Thursday, February 9th at the Red Rock Resort in Las Vegas during the 2012 D.I.C.E. (Design, Innovate, Communicate, Entertain) Summit. They will be hosted by comedian, actor and proud game enthusiast, Jay Mohr. This year’s IAAs will be streamed live on GameSpot.com in its entirety at 7:30pm PT / 10:30pm ET. “These games exemplify the highest standard of excellence and quality, from the breathtaking cinematics, to the bold storytelling and the innovative technology. ” said Martin Rae, president, Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. -

Annual Report2011 Web (Pdf)

ANNUAL REPORT 2 011 INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 1 The PEGI system and how it functions 4 TWO LEVELS OF INFORMATION 5 GEOGRAPHY AND SCOPE 6 HOW A GAME GETS A RATINg 7 PEGI ONLINE 8 PEGI EXPRESS 9 PARENTAL CONTROL SYSTEMS 10 CHAPTER 2 Statistics 12 CHAPTER 3 The PEGI Organisation 18 THE PEGI STRUCTURE 19 PEGI s.a. 19 Boards and Committees 19 PEGI Council 20 PEGI Experts Group 21 THE FOUNDER: ISFE 22 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATORS 23 NICAM 23 VSC 23 PEGI CODERS 23 CHAPTER 4 PEGI communication tools and activities 25 INTRODUCTION 25 SOME EXAMPLES OF 2011 ACTIVITIES 25 PAN-EUROPEAN ACTIVITIES 33 PEGI iPhone/Android app 33 Website 33 ANNEXES 34 ANNEX 1 - PEGI CODE OF CONDUCT 35 ANNEX 2 - PEGI SIGNATORIES 45 ANNEX 3 - PEGI ASSESSMENT FORM 53 ANNEX 4 - PEGI COMPLAINTS 62 INTRODUCTION © Rayman Origins -Ubisoft 3 INTRODUCTION Dear reader, PEGI can look back on another successful year. The good vibes and learning points from the PEGI Congress in November 2010 were taken along into the new year and put to good use. PEGI is well established as the standard system for the “traditional” boxed game market as a trusted source of information for parents and other consumers. We have almost reached the point where PEGI is only unknown to parents if they deliberately choose to ignore video games entirely. A mistake, since practically every child or teenager in Europe enjoys video games. Promoting an active parental involvement in the gaming experiences of their children is a primary objective for PEGI, which situates itself at the heart of that.