The Lure of Non-Credit Studio Art Classes for Adult Learners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginner Project Whittled Peg Rack

WOODWORKS: BEGINNER PROJECT WHITTLED PEG RACK Historically, peg racks like this one were hidden. They were fastened to the back walls of wardrobes in the days before wire coat hangers were invented. But this one’s too nice to hide! • You can adjust the length of your peg rack to fit any wall, and you can mount as many or as few pegs as you like. They don’t all have to look alike, either. As your whittling technique improves, the pegs will become more consistent. This project gives beginning woodworking students the opportunity to develop their whittling skills while doing some basic measuring, cutting, drilling and assembling to produce a great-looking household necessity. If you haven’t done it much before, you’ll find that whittling is relaxing and enjoyable, not to mention a nice break from machine work. You can also choose to cut the pegs with a scrollsaw to get some practice on that machine. And after you build the piece, you’ll learn how to apply and use finishes to protect the wood and keep it looking beautiful. –1– CONTINUED - WOODWORKS: BEGINNER PROJECT WHITTLED PEG RACK TOOLS REQUIRED Hand Tools Power Tools Miscellaneous – Fine (000) steel wool – Whittling knife – Drill or drill press with – Pencil (for Polyshades®) – Block plane 1/2" drill bit – Safety glasses – Respirator – Table saw – Carpenter’s glue – Gloves for finishing – Scrollsaw, stationary belt – Sandpaper – Mineral spirits and drum sanders (for – Clean, lint-free cloths – Water-filled metal container machine-made pegs) – Small square with tight-fitting lid – Woodcarver’s glove – Minwax® Wood Finish™ – Leather thumb guard Stain Brush SHOPPING LIST CUTTING LIST 1x4 pine or other softwood (whittled pegs) or oak or other Key Pcs. -

HARE Kit List

www.sarahvigarsart.com Kit List www.sarahvigarsart.com/tutorials This Kit List has been written to accompany my Carve a Puppet Hare tutorial series at www.sarahvigarsart.com/tutorials. To take part, you will need to purchase one of my Carving Kits, which are available in my online shop (www.sarahvigarsart.com/shop). Video 1 of the series (available now on the tutorials page) shows you exactly what’s inside a carving kit, and takes you through the tools, paints and equipment that you will need to complete the project, which are also itemised on this kit list. I recommend viewing Video 1 alongside reading this document. Carving Tools: Page 1 Sharpening Equipment: Page 2 Additional Carving Equipment: Page 2 Allergen Advice: Page 3 Dyes, Paints and Oils: Pages 3-5 Glues: Page 6 Assembly Tools and Equipment: Page 6-7 Other Consumables: Page 7 (Appendix: further sharpening equipment): Page 8 Carving Tools Where to find Item Description Where to find (UK) (non-UK) Throughout the tutorials, I am using Flexcut’s KN13 Detail There are many UK stockists of Knife. As the name suggests, Flexcut tools and you can usually If you live in the this knife is intended for carving order online. Here are a few, with USA, you can order detail, but I also find it direct links to the KN13 detail directly from perfectly workable for roughing out knife: Flexcut tools. small projects such as this one. Their full range of Axminster Tools: carving knives can be If you also want a knife for https://www.axminstertools.com/ found here: https:// roughing out larger projects, check flexcut-kn13-detail- www.flexcut.com/ Flexcut out Flexcut’s KN14 Roughing knife-600076 home/category/ whittling Knife, or their KN12 Cutting carving-knives knife Knife G&S Specialist Timber: https://www.toolsandtimber.co.uk/ If you live outside Of course, you may already have a flexcut-detail-knife-kn13 the USA, Flexcut whittling knife (or two!) of your have many stockists own. -

Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE June 1992 Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Although the words “he,” “him,” and “his” are used sparingly in this course to enhance communication, they are not intended to be gender driven or to affront or discriminate against anyone. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. NAVAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROGRAM MANAGEMENT SUPPORT ACTIVITY PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32559-5000 ERRATA NO. 1 May 1993 Specific Instructions and Errata for Nonresident Training Course TOOLS AND THEIR USES 1. TO OBTAIN CREDIT FOR DELETED QUESTIONS, SHOW THIS ERRATA TO YOUR LOCAL-COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER). THE LOCAL COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER) IS DIRECTED TO CORRECT THE ANSWER KEY FOR THIS COURSE BY INDICATING THE QUESTIONS DELETED. 2. No attempt has been made to issue corrections for errors in typing, punctuation, etc., which will not affect your ability to answer the question. 3. Assignment Booklet Delete the following questions and write "Deleted" across all four of the boxes for that question: Question Question 2-7 5-43 2-54 5-46 PREFACE By enrolling in this self-study course, you have demonstrated a desire to improve yourself and the Navy. Remember, however, this self-study course is only one part of the total Navy training program. Practical experience, schools, selected reading, and your desire to succeed are also necessary to successfully round out a fully meaningful training program. THE COURSE: This self-study course is organized into subject matter areas, each containing learning objectives to help you determine what you should learn along with text and illustrations to help you understand the information. -

Woodworking in Estonia

WOODWORKING IN ESTONIA HISTORICAL SURVEY By Ants Viires Translated from Estonian by Mart Aru Published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2016 26 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY 41017, USA Web: http://lostartpress.com Title: Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey Author: Ants Viires (1918-2015) Translator: Mart Aru Publisher: Christopher Schwarz Editor: Peter Follansbee Copy Editor: Megan Fitzpatrick Designer: Meghan Bates Index: Suzanne Ellison Distribution: John Hoffman Text and images are copyright © 2016 by Ants Viires (and his estate) ISBN: 978-0-9906230-9-0 First printing of this translated edition. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. This book was printed and bound in the United States. CONTENTS Introduction to the English Language Edition vii The Twisting Translation Tale ix Foreword to the Second Edition 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Literature, Materials & Methods 2 2. The Role Played by Woodwork in the Peasants’ Life 5 WOODWORK TECHNOLOGY 1. Timber 10 2. The Principal Tools 19 3. Processing Logs. Hollowing Work and Sealed Containers 81 4. Board Containers 96 5. Objects Made by Bending 127 6. Other Bending Work. Building Vehicles 148 7. The Production of Shingles and Other Small Objects 175 8. Turnery 186 9. Furniture Making and Other Carpentry Work 201 DIVISION OF LABOR IN THE VILLAGE 1. The Village Craftsman 215 2. Home Industry 234 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 283 Index 287 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION feel like Captain Pike. -

Whittling Chip in a Day Program

Whittling Chip in a Day Program Lisa Scarbrough Cubmaster, Pack 295, Guyton, GA S9-99-18 Whittling Chip in a Day 2 Requirements 1. Know the safety rules for handling a knife. 2. Show that you know how to take care of and use a pocketknife. 3. Make a carving with a pocketknife.* Work with your den leader or other adult when doing this. 4. Read, understand and promise to abide by the "Knives Are Not Toys" guidelines. 5. Read, understand and promise to abide by the "Pocketknife Pledge." *One of the items carved for requirements of the "Bear Claws" adventure may be used to fulfill Whittling Chip requirement 3. Bears: Bear Claws Requirements 1. Learn about three common designs of pocketknives. 2. Learn knife safety and earn your Whittling Chip.* 3. Do one of the following: A. Using a pocketknife, carve two items. B. With a pocketknife, safely perform each of these tasks: (1) Demonstrate how to cut a piece of rope, twine, or fishing line. (2) Open a sealed boX without damaging the contents. (3) Open a can with the can opener tool on a pocketknife. (4) Remove and replace the screws on an object with the screwdriver tool on a pocketknife. (5) Open a letter. Lisa Scarbrough, Pack 295, Guyton, GA • improvscouter.us Whittling Chip in a Day 3 Program Set aside two hours for your complete program, more if you think your Cubs will need eXtra time. Materials: • Pocketknives (each Cub should provide their own) - While using plastic knives is preferred by some, give them the opportunity to learn the responsibility and care of their own knife from the start. -

Art Teacher's Book of Lists

JOSSEY-BASS TEACHER Jossey-Bass Teacher provides educators with practical knowledge and tools to create a positive and lifelong impact on student learning. We offer classroom-tested and research-based teaching resources for a variety of grade levels and subject areas. Whether you are an aspiring, new, or veteran teacher, we want to help you make every teaching day your best. From ready-to-use classroom activities to the latest teaching framework, our value-packed books provide insightful, practical, and comprehensive materials on the topics that matter most to K–12 teachers. We hope to become your trusted source for the best ideas from the most experienced and respected experts in the field. TITLES IN THE JOSSEY-BASS EDUCATION BOOK OF LISTS SERIES THE SCHOOL COUNSELOR’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Dorothy J. Blum and Tamara E. Davis • ISBN 978-0-4704-5065-9 THE READING TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, FIFTH EDITION Edward B. Fry and Jacqueline E. Kress • ISBN 978-0-7879-8257-7 THE ESL/ELL TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Jacqueline E. Kress • ISBN 978-0-4702-2267-6 THE MATH TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Judith A. Muschla and Gary Robert Muschla • ISBN 978-0-7879-7398-8 THE ADHD BOOK OF LISTS Sandra Rief • ISBN 978-0-7879-6591-4 THE ART TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, FIRST EDITION Helen D. Hume • ISBN 978-0-7879-7424-4 THE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE LOVER’S BOOK OF LISTS Joanna Sullivan • ISBN 978-0-7879-6595-2 THE SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Ronald L. -

Whittling 3–5Owl

PROJECT WORK SHEET Whittling 3–5 Owl Another Whittling Whimsy Whittling is a time-tested hobby that is both relaxing and fun. However, starting out can be intimidating. This easy project helps you develop basic fundamental techniques and helps you build confidence in your abilities. Completion of this decades old project requires all of the basic cuts: Stop cut, Push cut, Pull cut, Chip cut (basic triangular), and V-cuts. The project provides practice for whittling in-the-round to help develop 3D concepts. Some whittlers claim this project can be completed in 3 minutes—others in 5 minutes, but experience says—35 minutes! Supplies Materials Tools Wood: Basswood, poplar, or branch Carving knife: basic bench knife (at lease 3” long; with square base) Optional: U-gouge (1/4” #6) Suggested: 1” x 1” x 3” or 1-1/2” x 1-1/2” x 4” Saw Sandpaper or emery boards Pencil Hardware: Small screw-eye (optional) Flexible ruler (6-in) Finish supplies Scope The project uses traditional whittling skills to complete a whittling whimsy, blending the techniques of the 3-Minute Owl and 5-Minute Owl projects. Pattern See PAGE 5 for measurements and layout diagrams. Objective To complete an in-the-round project to boost rounding and basic knife skills and project process skills. 1 6 Project Work Sheet Another Whittling Whimsy Whittling a 3-5 Minute Owl Steps Step Directions Image Selecting wood 1 Use a basswood block, measuring 1” x 1” x 6” —OR— Note: This project does not 1-1/2” x 1-1/2” x 4” require great detail. -

P R O D U C T G U Id E

2010 PRODUCT GUIDE NEW! Spyderco KniVes 2010 SPYDERCO CONTENTS C28GFG Dragonfly G-10 oliageF Green 13 CLIPIT Folding Knives 2 C28PT Dragonfly with Dragonfly etching 13 C36GOR Military Model Orange 15 SLIPIT Non-Locking Folding Knives 31 C36LH Military Model Left Hand 15 The Spyderco Way 35 C36TI Ti-Mil Military Titanium 16 C77YL SpyderHawk Salt 39 Whale Blade Project 36 C90BK Stretch Lightweight 21 Salt Series Knives 37 C90BL Stretch Lightweight ZDP-189 21 C91BK Pacific Salt Black Blade 38 Fixed Blade Knives 44 C94 UK Penknife Leaf-Shape Lightweight 32 C94-3 UK Penknife Drop-Point Lightweight 32 Sprint Runs 47 C94-2 UK Penknife Rescue Lightweight 33 Sharpeners 48 C101 Manix2 86mm 22 C123Ti Sage Titanium 26 Accessories 54 C129 Cat 28 Warranty Information 57 C130 Chicago 28 C131 Bob Terzuola SLIPIT 34 Steel Elements & Creation 72 C132 Chockwe 29 Glossaries 74 C133 Bug 34 C134 Gayle Bradley Folder 29 Patents & Trademarks 75 C136 Persistence 25 Steel Chart 78 C137 HoneyBee 34 FB05 Temperance2 45 Index 80 FB24 Jumpmaster 43 FB25 Warrior 41 FB26 Bushcraft 46 BYRD KNIFE CONTENTS LFG3 Ladybug Lightweight Foliage Green 30 Folding Knives 58 NEW! Sprint RUns 2010 Sharpener 70 FB02OR Bill Moran Drop Point Orange 47 Accessories 71 C56CF Tim Zowada Carbon Fiber 47 C64JBG Meerkat Gray 47 Warranty Information 71 C101FG Manix2 Foliage Green XHP 47 Index 80 LBK3HB Ladybug Hawkbill 47 CLIPITS CLIPITS Quality is the Product of a Good Attitude® Telling you what’s exceptional about Spyderco Knives in a catalog is just It’s been thirty years since we started making knives. -

WOODCARVING SUPPLIES 2021 Catalog, Vol. 21

STADTLANDER WOODCARVINGS WOODCARVING SUPPLIES 2021 Catalog, Vol. 21 KNIVES GOUGES CHIP CARVING POWER CARVING WOODBURNING WOOD BLANKS BASSWOOD PLATES ROUGHOUTS Sunflower BOOKS Carved by Bob Stadtlander AND A WHOLE LOT MORE !!!! 2951 Frost Road Mantua, OH 44255 Phone: (330) 931-7847 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our website and order on-line at www.stadtlandercarvings.com $1.00 STADTLANDER WOODCARVINGS www.stadtlandercarvings.com PHONE: (330) 931-7847 HELLO FELLOW WOODCARVERS: We hope you enjoy perusing this volume of our catalog. All products are those that I use myself or recom- mend to woodcarving friends. Please visit our website at www. stadtlandercarvings.com to order from our secure on-line internet store. Our store also contains additional information on many of our products . Thanks to all who have supported us over the years. Happy carving! Robert Stadtlander VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.STADTLANDERCARVINGS.COM! Prices effective 1-1-2021 and are subject to TABLE OF CONTENTS change without notice NEW ITEMS …………………………………………….1A, 1B BOOKS KNIVES AND GOUGES NEW LISTINGS………………...1A MURPHY…………….………………………………...1 ANIMAL………………….…….. 57-58 AQUATIC…………….……….. 58 CHIP CARVING AND KOLROSING………………..1 ARCHITECTURAL / DECORATIVE ....58 JOHN DUNKLE KNIVES ……………..……………..2 BASICS………………………...58 OZARK COUNTY CARVING (OCC) TOOLS……...3-5 BEGINNER/YOUTH/SOAP...…..59 DOCKYARD MICROGOUGES………………………5 BIRD…………………………...59 ROD HARDY KNIVES………………………………..6 CANES/WALKING STICKS….….60 CARICATURE…………………....60-62 HENRY TAYLOR PALM TOOLS….………………….6 CAST -

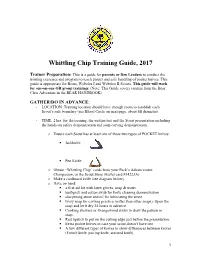

Whittling Chip Training Guide, 2017

Whittling Chip Training Guide, 2017 Trainer Preparation: This is a guide for parents or Den Leaders to conduct the training exercises and program to teach proper and safe handling of pocket knives. This guide is appropriate for Bears, Webelos I and Webelos II Scouts. This guide will work for one-on-one OR group trainings. (Note: This Guide covers content from the Bear Claw Adventure in the BEAR HANDBOOK) GATHER/DO IN ADVANCE: - LOCATION: Training location should have enough room to establish each Scout’s safe boundary (see Blood Circle on next page, about 6ft diameter). - TIME: 2 hrs. for the training, the written test and the Scout presentation including the hands-on safety demonstration and soap carving demonstration. o Ensure each Scout has at least one of these two types of POCKET knives: § Jackknife: § Pen Knife: o Obtain “Whittling Chip” cards from your Pack’s Advancement Chairperson, or the Scout Store (wallet card #34223A) o Make a cardboard knife (see diagram below). o Have on hand: § a first aid kit with latex gloves, soap & water § toothpick and cotton swab for knife cleaning demonstration § sharpening stone and oil for lubricating the stone § Ivory soap for carving practice (softer than other soaps). Open the soap and let it dry 24 hours in advance. § Cooking skewers or Orangewood sticks to draw the pattern in soap. § Red lipstick to put on the cutting edge just before the presentation. § Extra pocket knives in case your scout doesn’t have one § A few different types of knives to show differences between knives (French knife, pairing knife, serrated knife) 1 Definition of Terms and Activities The following is a list of the terms and activities to be taught during this training exercise. -

James Gros See Page 2

era Publi calton of the American Crafts Council James Gros See page 2 Second Class Postage Paid at New York, NY and at Additional Mailing Office . ... - ".-.- . _. _._.- ._-_._--_._._----_._-------- CRAFT WORLD of Craft Horizons ACC NEWS Vol. XXXVIII No.4 Rose Slivka, Safari Off Editor-in-Chief Patricia Dandignac , OPEN to Africa Managing Editor Michael Lauretano, DOOR Fertility dolls and ceremonial Art Director Samuel Scherr masks, metalsmithing and pot Edith Dugmore, tery-these are some highlights Assistant Editor As of the April issue, you may of "The Art and Tradition of Michael McTwigan, have noticed that I revised the Editorial Assistant West Africa," a three-week tour heading of this column from of Senegal, Ghana, Togo, and Ni Isa bella Brandt, " Open Windows" to " Open Editorial Assistant geria (August 2-27, 1978, and Door," since I felt strongly that Anita Chmiel, January 7-31,1979). Sponsored Advertising Department the ncw and proper direction of by ACC and Art Safari, Inc., the the American Crafts Council tour is led by Art Safari codirec Editorial Board should invite an easy access to Junius Bird tor James Gross and fiber artist Jean Delius Arline Fi sc h the flow of information and ideas, Eleanor Dickinson. For the Au Persis Grayson not only within the U.S. but also gust tour contact, posthaste: 1924-1978 Robert Beverly Hale abroad. An open door is an invi Steven Adler, 800-223-0694, toll Lee Hall tation to exchange and growth. frce; or write ACC/ Art Safari. Pol ly Lada-Mocarski Another equally significant Jean Delius, jcweler and associate Harvey Littleton change is this month's CRAFT professor at New York State Col Ben Ra eburn HORIZONS with its section of lege at Oswego, died suddenly Ed Rossbach CRAFT WORLD. -

Gerber Gear Full Line Product Catalog

PRODUCT CATALOG + ii 1 Badassador (noun) – doing whatever it takes, even if that’s everything you got; finding out you have more inside than you thought; out there in the woods and swamp and sea, in it; the act of being Unstoppable. BLOG.GERBERGEAR.COM/BADASSADORS/ 2 AMERICAN ORIGINAL BORN ON THE BUILT TO SPIRIT INNOVATOR BATTLEFIELD ENDURE Built through grit, passion Gerber products challenge Gerber understands trust, Made to save time or save and hard work, Gerber's the staus quo, and bring and knows great products the day, Gerber tools are competitive spirit is new solutions to common can be the difference built for use and will stand unwavering. problems. between life and death. the test of time. 3 TOC KNIVES 5 New 6 Fixed Blade 22 Assisted Opening 42 Automatic 53 Folding Clip 56 Folding Sheath 78 Multi-Blade 84 Pocket Folding 85 CUTTING TOOLS 88 New 89 Axes 92 Machetes 97 Pruners + Shears 1Ø2 Saws 1Ø4 MULTI-TOOLS 1Ø9 New 111 One-Hand Opening 112 Butterfly Opening 116 Solid State 123 Specialized 125 Accessories 129 LIGHTING 130 EQUIPMENT 137 New 139 Accessories 144 Breaching 148 Kits 149 Sharpeners 155 Shovels 157 Specialized 159 INDEX 162 GERBERGEAR.COM 4 KNIVES + KNIVES | FIXED BLADE 5 Ø6 AUTO™ 1ØTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Honoring the American heritage and time-tested durability of the Ø6 Automatic family, Gerber proudly presents an innovative evolution of everything that made the original the best in its class. The Ø6 Automatic 1Øth Anniversary knife is a special edition celebration of Gerber’s craftsmanship, design, and spirit.