Advisory Support for the Development of the Buddhist Circuit in South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

A Report on 'Domestic Tourism Expenditure'

A Report on ‘Domestic Tourism Expenditure’ In Uttar Pradesh Based on Pooled Data (Central and State Sample) of 72nd Round NSS Schedule 21.1 (July 2014 to June 2015) ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS DIVISION PLANNING DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF UTTAR PRADESH LUCKNOW Website: http://updes.up.nic.in Email: [email protected] PREFACE The Seventy second round of NSSO (July 2014 to June 2015) was devoted exclusively for collection of data on 'Domestic Tourism Expenditure'. Uttar Pradesh State is a partner in NSS surveys since 9th round (1955), generally on equal matching basis of samples. The present report on "A Report on ‘Domestic Tourism Expenditure’ In Uttar Pradesh" is based on the result of pooled data of central and state sample of Uttar Pradesh. National Statistical Commission constituted a professional committee under the Chairmanship of Prof. R.Radhakrishna, to identify the preconditions for pooling of Central and State Sample NSS data, to suggest appropriate methodology for pooling the data and to bridge the data gaps and in turn strengthen the database for decentralized planning and governance. The necessity for pooling the Central and State sample data arose due to the growing need for improving the precision of estimates of policy parameters such as the labour force participation, level of living and well being, incidence of poverty, State Domestic Product (SDP), District Domestic Product(DDP) etc., and for strengthening the database at district level required for decentralized governance. Accordingly the NSC professional committee has recommended certain poolability tests and the methodologies for pooling of Central and State sample data of NSS. In the workshop which was held on 19th and 20thSeptember 2018 at Kolkata, it was demonstrated about the poolability tests and pooling the two sets of data and estimating the parameters based on two methods- (1) Matching ratio method and (2) Inverse Weight of the Variance of estimates method. -

Opportunities for the Development of Drowning Interventions in West Bengal, India: a Review of Policy and Government Programs M

Gupta et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:704 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08868-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Opportunities for the development of drowning interventions in West Bengal, India: a review of policy and government programs M. Gupta1* , A. B. Zwi2 and J. Jagnoor3 Abstract Background: Four million people living in the Indian Sundarbans region in the state of West Bengal face a particularly high risk of drowning due to rurality, presence of open water, lack of accessible health systems and poor infrastructure. Although the World Health Organization has identified several interventions that may prevent drowning in rural low-and middle-income country contexts, none are currently implemented in this region. This study aims to conduct contextual policy analysis for the development of a drowning program. Implementation of a drowning program should consider leveraging existing structures and resources, as interventions that build on policy targets or government programs are more likely to be sustainable and scalable. Methods: A detailed content review of national and state policy (West Bengal) was conducted to identify policy principles and/or specific government programs that may be leveraged for drowning interventions. The enablers and barriers of these programs as well as their implementation reach were assessed through a systematic literature review. Identified policies and programs were also assessed to understand how they catered for underserved groups and their implications for equity. Results: Three programs were identified that may be leveraged for the implementation of drowning interventions such as supervised childcare, provision of home-based barriers, swim and rescue skills training and community first responder training: the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), Self-Help Group (SHG) and Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) programs. -

Hospitality Servicesimpacting Uttar Pradesh's Tourism Industry

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020 Hospitality Servicesimpacting Uttar Pradesh's Tourism Industry Mr. Gaurav Singh Asst. Professor (School of Hotel Management and Tourism) Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India ABSTRACT: Tourism has been crucial to social progress as well as an important tool throughout human history to extend socio-economic and cultural interaction. This encourages international connections, markets expanding, broad-based jobs and income production, as a source and effect of economic growth. The tourist sector is a major contributor to many nations 'gross national products. This is among the world's fastest-growing sectors. Today, a commonly known trend is the promotion of vacation attractions and the travel infrastructure. Investment in tourist infrastructure boosts economic development, catalyses income and job generation, which in turn contributes to more development in tourism demand, which induces a corresponding investment cycle within a virtuous ring.Expenditure on tourism produces numerous impacts in the value chain, with robust outreach. In addition to the need for a range of goods and services, tourism also provides opportunities for the relevant industries.The Tourism Growth Policy itself can be an instrument for positive economic and social change.Tourism supports social harmony and connection with the group. It encourages the restoration and conservation by adding importance to history, heritage, climate, atmosphere and ecology.In this paper various consideration points of touring have been mentioned. The analyses find few dimensions of service efficiency in Uttar Pradesh's Tourism Industry. Keywords Hospitality, Tourism, Business, Facility, Service, Uttar Pradesh 1. INTRODUCTION India has a huge bouquet of attractions for tourists to boast about. -

COVID Lockdown, How People Managed and Impact of Welfare Schemes on Informal Sector Workers: Evidence from Delhi Slums* Saudamini Das1 Ajit Mishra2

COVID lockdown, how people managed and impact of welfare schemes on informal sector workers: Evidence from Delhi slums Saudamini Das Ajit Mishra COVID lockdown, how people managed and impact of welfare schemes on informal sector workers: Evidence from Delhi slums* Saudamini Das1 Ajit Mishra2 Abstract COVID-19 pandemic is likely to accentuate poverty and vulnerability of people at the margin for a number of reasons like lockdown, relocation to native places having no scope for gainful employment, health effects, opening of work with many restrictions, future uncertainty, etc. Following the lockdown in March, the central and state governments announced many welfare measures like direct cash transfer, food grain distribution through public distribution system, community kitchen and many others to reduce the negative effect of the lockdown and provide some basic minimum income to the poorer class, though the effects are yet to be assessed. This paper studies 199 slum households in Zakhira and Kirti Nagar areas of Delhi during April- May 2020 to find out their coping and the benefits they received from these welfare schemes. Sample consisted of people like wage labour, e-rickshaw drivers, auto drivers, people doing small private jobs, street vendors, construction workers, etc. The results show the households to have consumed 2.5 meals per day and have used up their savings or have borrowed from friends. The welfare schemes were marginally helpful. Only 76% of the households were benefited by at least one of the nine schemes announced by the government and the average gain was a meagre Rs984/ per household, with an average family size of 5.8 persons, for one lockdown month. -

SSB Smartly SUPER Current Affairs MCQ PDF

Boost Your Exam Preparations With Smartly By SSB Institute Bank I Insurance I Railway I SSC I UPSC I MPSC I DEFENCE & Other Government Exams Available on :- Contact :- 0-83026-55216 Visit on :- www.smartlybyssb.com India's Most Affordable Smartly Practice Set To Boost Your Exam Preparation 1 FOLLOW US : OFFICIAL WEBSITE, TELEGRAM , FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM, YOUTUBE, PLAYSTORE Boost Your Exam Preparations With Smartly By SSB Institute Bank I Insurance I Railway I SSC I UPSC I MPSC I DEFENCE & Other Government Exams Available on :- Contact :- 0-83026-55216 Visit on :- www.smartlybyssb.com India's Most Affordable Smartly Practice Set To Boost Your Exam Preparation Q. Which Central American country has been declared malaria-free by WHO? A. Columbia C. Ecuador B. El Salvador D. Brazil Answer: B Ø World Health Organization (WHO) has granted the Malaria -free Certiicate to El Salvador as a result of 50 years of commitment. El Salvador has become the 1st Central American country to become a certiied malaria-free. WHO IN NEWS 2021 § WHO Declares El Salvador Malaria-Free § Health Minister Harsh Vardhan chairs 148th session of WHO Executive Board § Anil Soni Appointed First Chief Of The WHO Foundation § Preeti Sudan appointed to WHO’s Panel For Pandemic Preparedness § World Health Organization certiies Africa free from wild Polio § World Health Day observed globally on 7 April § Global health Emergency declared over Coronavirus by WHO § US formally announced its withdrawal from WHO About World Health Organization (WHO) § Formation : 7 April 1948 § Headquarters : Geneva, Switzerland 2 FOLLOW US : OFFICIAL WEBSITE, TELEGRAM , FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM, YOUTUBE, PLAYSTORE Boost Your Exam Preparations With Smartly By SSB Institute Bank I Insurance I Railway I SSC I UPSC I MPSC I DEFENCE & Other Government Exams Available on :- Contact :- 0-83026-55216 Visit on :- www.smartlybyssb.com § Director General : Tedros Adhanom (Ethiopia) § Deputy Director General : Soumya Swaminathan (Indian) Q. -

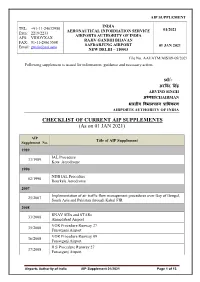

Sd/- CHECKLIST of CURRENT AIP SUPPLEMENTS (As on 01 JAN 2021)

AIP SUPPLEMENT INDIA TEL: +91-11-24632950 AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION SERVICE 01/2021 Extn: 2219/2233 AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA AFS: VIDDYXAX RAJIV GANDHI BHAVAN FAX: 91-11-24615508 SAFDARJUNG AIRPORT Email: [email protected] 01 JAN 2021 NEW DELHI – 110003 File No. AAI/ATM/AIS/09-09/2021 Following supplement is issued for information, guidance and necessary action. sd/- हﴂ द सﴂ अरव ARVIND SINGH अ鵍यक्ष/CHAIRMAN भारतीय व मानपत्तन प्राधिकरण AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA CHECKLIST OF CURRENT AIP SUPPLEMENTS (As on 01 JAN 2021) AIP Title of AIP Supplement Supplement No. 1989 IAL Procedure 33/1989 Kota Aerodrome 1990 NDB IAL Procedure 02/1990 Rourkela Aerodrome 2007 Implementation of air traffic flow management procedures over Bay of Bengal, 25/2007 South Asia and Pakistan through Kabul FIR 2008 RNAV SIDs and STARs 33/2008 Ahmedabad Airport VOR Procedure Runway 27 35/2008 Fursatganj Airport VOR Procedure Runway 09 36/2008 Fursatganj Airport ILS Procedure Runway 27 37/2008 Fursatganj Airport Airports Authority of India AIP Supplement 01/2021 Page 1 of 13 40/2008 Establishment, Operation of a Central Reporting Agency NDB Circling Procedure Runway 04/22 46/2008 Gondia Airport VOR Procedure Runway 04 47/2008 Gondia Airport VOR Procedure Runway 22 48/2008 Gondia Airport 2009 RNAV SIDs & STARs 29/2009 Chennai Airport 2010 Helicopter Routing 09/2010 CSI Airport, Mumbai RNAV-1 (GNSS or DME/DME/IRU) SIDS and STARs 14/2010 RGI Airport, Shamshabad 2011 NON-RNAV Standard Instrument Departure Procedure 09/2011 Cochin International Airport RNAV-1 (GNSS) SIDs and STARs 61/2011 Thiruvananthapuram Airport NON-RNAV SIDs – RWY 27 67/2011 Cochin International Airport RNP-1 STARs & RNAV (GNSS) Approach RWY 27 68/2011 Cochin International Airport 2012 Implementation of Data Link Services I Departure Clearance (DCL) 27/2012 ii Data Link – Automatic Terminal Information Service (D-ATIS) iii Data Link – Meteorological Information for Aircraft in Flight (D-VOLMET) 38/2012 Changes to the ICAO Model Flight Plan Form 2013 RNAV-1 (GNSS) SIDs & STARs 37/2013 Guwahati Airport. -

Fostering Sustainable Tourism In

TITLE Smart Cities: Fostering Sustainable Tourism in U.P. YEAR October, 2017 AUTHOR Strategic Government Advisory (SGA), YES BANK No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photoprint, microfilm or any other COPYRIGHT means without the written permission of YES BANK LTD. This report is the publication of YES BANK Limited (“YES BANK”) so YES BANK has editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, YES BANK will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader’s reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third party contents and third- party resources. YES BANK takes no responsibility for third party content, advertisements or third party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. Further, YES BANK does not assume any responsibility or liability for any loss or damage, including personal injury or death, resulting from use of this report or from any content for communications or materials available on this report. The contents are provided for your reference only. The reader/ buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by YES BANK, YES BANK does not operate, control or endorse any other information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. All other information, products and services offered through the report are offered by third parties, which are not affiliated in any manner to YES BANK. -

Current Affairs May 2020

MISSION CAPF HUB BY SWAPNIL WALUNJ & TEAM CURRENT AFFAIRS MAY 2020 FEATURES OF CURRENT AFFAIRS MAGAZINE COVERAGE – THE HINDU, INDIAN EXPRESS. PIB GKTODAY MONTHLY MAGAZINE VISION IAS MONTHLY MAGAZINE Telegram channel for CAPF = t.me/missioncapfhub (click here) Telegram channel for CDS/NDA/AFCAT/INET = t.me/TheDefenceHub (click here) Our Youtube channel = missioncapfhub (click here) Our website = www.missioncapfhub.com (click here) Copyright © by MISSION CAPF HUB All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of mission capf hub JOIN TELEGRAM @MISSIONCAPFHUB / JOIN OUR DEFENCE CHANNEL @THEDEFENCEHUB Page 1 MISSION CAPF HUB BY SWAPNIL WALUNJ & TEAM INDEX OF CURRENT AFFAIRS SERIA SECTION/TOPIC PAGE NO. L NO. 1) AWARDS/MEDALS/HONORS/PRIZE 4 2) REPORTS /INDEX/SURVEY/STUDY 5 3) GOVT. SCHEMES/PORTAL /APPS/INITIATIVES 7 4) ECONOMY/BANKING 10 5) DEFENCE NEWS / MILITARY EXERCISE 12 6) ENVIRONMENTS 14 7) INTERNATIONAL NEWS 16 8) SPORTS 20 9) PERSONS IN NEWS 20 10) PLACES IN NEWS – SUMMITS/CONFERENCE 21 11) IMPORTANTS DATES & EVENTS 21 12) STATES IN NEWS 23 13) SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 25 14) FESTIVALS/GI TAGS 27 15) BOOKS 28 16) MISCELLANEOUS 29-32 JOIN TELEGRAM @MISSIONCAPFHUB / JOIN OUR DEFENCE CHANNEL @THEDEFENCEHUB Page 2 MISSION CAPF HUB BY SWAPNIL WALUNJ & TEAM ANALYSIS OF CURRENT AFFAIRS PREVIOUS YEARS QUESTIONS PAPERS (2015-2019) SERIAL SECTION/TOPIC NO. OF NO. QUESTIONS 1) AWARDS/MEDALS/HONORS/PRIZE 14 2) REPORTS /INDEX/SURVEY/STUDY 04 3) GOVT. -

Development of Iconic Tourism Sites in India

Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) INCEPTION REPORT May 2019 PREPARATION OF BRAJ DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR BRAJ REGION UTTAR PRADESH Prepared for: Uttar Pradesh Braj Tirth Vikas Parishad, Uttar Pradesh Prepared By: Design Associates Inc. EcoUrbs Consultants PVT. LTD Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 1 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Design Associates Inc. and Ecourbs Consultants for the internal consumption and use of Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishad and related government bodies and for discussion with internal and external audiences. This document has been prepared based on public domain sources, secondary & primary research, stakeholder interactions and internal database of the Consultants. It is, however, to be noted that this report has been prepared by Consultants in best faith, with assumptions and estimates considered to be appropriate and reasonable but cannot be guaranteed. There might be inadvertent omissions/errors/aberrations owing to situations and conditions out of the control of the Consultants. Further, the report has been prepared on a best-effort basis, based on inputs considered appropriate as of the mentioned date of the report. Consultants do not take any responsibility for the correctness of the data, analysis & recommendations made in the report. Neither this document nor any of its contents can be used for any purpose other than stated above, without the prior written consent from Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishadand the Consultants. Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 2 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................................... -

NEWSLETTER NEFOR FREE PUBLIC CIRCULATION Vol

NEWSLETTER NEFOR FREE PUBLIC CIRCULATION Vol. XIII. No. 10, October, 2011 MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA A Monthly Newsletter on the North Eastern Region of India Also available on Internet at : htpp:mha.nic.in We must be the change we wish to see. Mahatma Gandhi DEVELOPMENTS WITH REFERENCE TO C O N T E N T S NORTH EASTERN REGION DEVELOPMENTS WITH REFERENCE TO NORTH 1. A review committee meeting on monitoring of EASTERN REGION ceasefire with NSCN/K was held on October 10, ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT UNDER CIVIC ACTION 2011. PROGRAMME BY CENTRAL ARMED POLICE FORCES 2. On October 13-14, 2011 tripartite talks were held with DHD/N and DHD/J for finalization of Memorandum of PROGRAMMES UNDERTAKEN BY MINISTRY OF I&B Settlement. IN THE NORTH EASTERN REGION 3. On October 15, 2011, a meeting was held between MANIREDA LIGHTING UP MANIPUR MHA and Chief of General Staff of Myanmar Army to SELF-HELP GROUPS TRANSFORMING LIVES IN discuss security related issues. ASSAM 4. A tripartite meeting involving the representatives of Government of Assam and ULFA was held on NABAKISHORE SINGH, MANIPUR’S RISING STAR 25.10.2011 under the Chairmanship of Union Home IMPLEMENTATION OF NRCP WORKS IN THE STATE Secretary (Shri R.K Singh) at New Delhi to discuss OF SIKKIM demands submitted by ULFA on 05.08.2011 to Union Home Minister. WATER QUALITY TESTING LABORATORY Representatives of ULFA were headed by Shri Arabinda ESTABLISHED IN SIKKIM Rajkhowa (Chairman, ULFA). Chief Secretary, SIKKIM, GOA AND DELHI RANKED NO. 1 IN STATE Government of Assam (Sh. -

Daily Current Affairs June 27 2020

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS JUNE 27 2020 USE CODE Y216 VISIT: STORE.ADDA247.COM DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS JUNE 27 2020 USE CODE Y216 VISIT: STORE.ADDA247.COM DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS JUNE 27 2020 USE CODE Y216 YESTERDAY CURRENT AFFAIRS QUICK REVISION VISIT: STORE.ADDA247.COM permanent military base in the Indian Ocean- Iran eBlood Services Mobile App- Dr. Harsh Vardhan Kushinagar airport as an International airport- Uttar Pradesh United Nations has honoured which state’s Health minister- Kerala FabiFlu’ the first oral favipiravir-approved medication in India- Glenmark Pharma Limited US Gold Currency Inc and Blockfills to introduce world’s 1st monetary gold-backed- IBMC Financial Professionals Group Nishtha Vidyut Mitra Scheme- Women (MP) Mukhyamantri SHRAMIK (Shahri Rozgar Manjuri for Kamgar) Yojna”.- Jharkhand United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees- $10 million Indian Financial Technology & Allied Services (IFTAS). –CEO- N Rajendran “KBL Micro Mitra” to provide financial assistance- Karnataka Bank Information about Country of Origin- Government e-Marketplace Partnered with Reliance Jio Tv to educate students- Haryana DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS JUNE 27 2020 USE CODE Y216 VISIT: STORE.ADDA247.COM Amid the growing outbreak of Corona virus (COVID-19) in India, National Health Authority (NHA), which is responsible for the implementation of the Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJA) has to bring the cost of testing and treatment of corona virus infection under the ambit of this scheme DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS JUNE 27 2020 USE CODE Y216 VISIT: STORE.ADDA247.COM YESTERDAY HOME WORK ANSWER EMCs 2.0 scheme will help India to become the mobile manufacturing hub in the world.