Contested Consecrations and the Pursuit of Ecclesiastical Independence in Scotland And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent

( 55 ) ODO, BISHOP OF BAYEUX AND EARL OF KENT. BY SER REGINALD TOWER, K.C.M.G., C.Y.O. IN the volumes of Archceologia Cantiana there occur numerous references to Bishop Odo, half-brother of William the Conqueror ; and his name finds frequent mention in Hasted's History of Kent, chiefly in connection with the lands he possessed. Further, throughout the records of the early Norman chroniclers, the Bishop of Bayeux is constantly cited among the outstanding figures in the reigns of William the Conqueror and of his successor William Rufus, as well as in the Duchy of Normandy. It seems therefore strange that there should be (as I am given to understand) no Life of the Bishop beyond the article in the Dictionary of National Biography. In the following notes I have attempted to collate available data from contemporary writers, aided by later historians of the period during, and subsequent to, the Norman Conquest. Odo of Bayeux was the son of Herluin of Conteville and Herleva (Arlette), daughter of Eulbert the tanner of Falaise. Herleva had .previously given birth to William the Conqueror by Duke Robert of Normandy. Odo's younger brother was Robert, Earl of Morton (Mortain). Odo was born about 1036, and brought up at the Court of Normandy. In early youth, about 1049, when he was attending the Council of Rheims, his half-brother, William, bestowed on him the Bishopric of Bayeux. He was present, in 1066, at the Conference summoned at Lillebonne, by Duke William after receipt of the news of Harold's succession to the throne of England. -

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For entities named after Saint Anselm, see Saint Anselm's. Anselm of Canterbury Archbishop of Canterbury Province Canterbury Diocese Diocese of Canterbury See Archbishop of Canterbury Appointed 1093 Reign ended 21 April 1109 Predecessor Lanfranc Successor Ralph d'Escures Other posts Abbot of Bec Orders Consecration 4 December 1093 Personal details Birth name Anselmo d'Aosta c. 1033 Born Aosta, Kingdom of Burgundy 21 April 1109 (aged 75) Died Canterbury, Kent, England Buried Canterbury Cathedral Denomination Roman Catholic Gundulf de Candia Parents Ermenberga of Geneva Sainthood Feast day 21 April Portrayed with a ship, representing Attributes the spiritual independence of the Church. Anselm of Canterbury (Aosta c. 1033 – Canterbury 21 April 1109), also called of Aosta for his birthplace, and of Bec for his home monastery, was a Benedictine monk, a philosopher, and a prelate of the Church who held the office of Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109. Called the founder of scholasticism, he is famous as the originator of the ontological argument for the existence of God. Born into the House of Candia, he entered the Benedictine order at the Abbey of Bec at the age of 27, where he became abbot in 1079. He became Archbishop of Canterbury under William II of England, and was exiled from England from 1097 to 1100, and again from 1105 to 1107 under Henry I of England as a result of the investiture controversy, the most significant conflict between Church and state in Medieval Europe. Anselm was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1720 by a Papal Bull of Pope Clement XI. -

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

John Stapylton Habgood

Communication The Untidiness of Integration: John Stapylton Habgood The Untidiness of Integration: John Stapylton Habgood Kevin S. Seybold uring the Middle Ages, it was not Born in 1927, John Habgood was edu- Dunusual for theologians to study the cated at King’s College, Cambridge, where physical world. In fact, there was an he read natural sciences specializing in amazing lack of strife between theology and physiology. After earning a Ph.D., he became science at this time. One reason for this a demonstrator in pharmacology and a fel- cooperation was the large number of indi- low of his college at Cambridge. In response viduals trained in both theology and medi- to a mission effort in Cambridge, Habgood eval science. It was the medieval theologian converted to Christianity in 1946 and began who tried to relate theology to science and the life-long process of wrestling with his science to theology.1 Today, it is uncommon new faith, a process that is central to his to have a theologian also easily conversant understanding of what it means to be a 2 Kevin S. Seybold in the scientific literature. John Polkinghorne, Christian. Habgood eventually served in a Arthur Peacocke, and Alister McGrath are number of church roles, but maintained a well-known contemporary examples of sci- dedication to his family and the people of his Born in 1927, entists who later have been trained in parish (regardless of how large that parish theology and turned their attention to the became). He also wrote several books dur- John Habgood integration of the two. -

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27 Scripture/Memory Verse [Be] eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace: There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call; one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all. Ephesians 4: 3 – 6 Lesson Goals & Objectives Goal: The students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the fact that we belong to a church that is larger than our own parish: we are part of The Episcopal Church (in America) which is also part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Objectives: The students will become familiar with the meanings of the terms, Episcopal, Anglican, Communion (as referring to the larger church), ethos, standing committee, presiding bishop and general convention. The students will understand the meaning of the “Four Instruments of Unity:” The Archbishop of Canterbury; the Meeting of Primates; the Lambeth Conference of Bishops; and, the Anglican Consultative Council. The students will encounter the various levels of structure and governance in which we live as Episcopalians and Anglicans. The students will learn of and appreciate an outline of our history in the context of Anglicanism. The students will see themselves as part of a worldwide communion of fellowship and mission as Christians together with others from throughout the globe. The students will read and discuss the “Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral” (BCP pages 876 – 877) in order to appreciate the essentials of an Anglican identity. Introduction & Teacher Background This lesson can be as exciting to the students as you are willing to make it. -

St Andrews Town

27 29 A To West Sands 28 9 St Andrews 1 to THE SC 1 D O u THE LINK S RES Town Map n 22a 54 de 32 41 42 e BUTT a Y PK 30 43 nd L S 0 100m 200m 300m euc 33 40 W YND 44 55 hars NO 31 53 22 MURRA C R 19 TH S 34 35 56 I BOTSFOR TREE T B D 39 46 SCALE 20 A CR T 30a 45 57 Y T 36 North 2 18 RO 38 47 51 Haugh 48 49 A ST 31b 75a 17 21 T 50 D HOPE ST 60 52 58 N CASTLE S 75b 11 16 23 COLLEGE 4 GREYFRIARS GDNS 59 UNION S 3 ET STRE ET CHURCH S 15 ST MARY’S PLACE MARK 12 BELL STRE 62 61 75 D 85 10 Kinburn OA 24 25 Pier R S T 76 14 Park KE 3 5 13 Y ET 79 D 26 67 66 LE ET ABBEY ST 77 B 33a WESTBURN All Weather U 65 THE PENDS O SOUTH63 STRE QUEENS GARDEN Pitches & D Y GARDENS Running W 78 AR 9 TREET 68 74 Track DL ARGYLE S 64 69 LANE 8 KENNED AW DO G D N N B E ST LEONARD’S A S C L R A 4 D L SO ID 70 P A N S BBEY G E G S 71 D E ID N 70a W Playing S ALK 6 S ST 72 N Fields RO E E AC E R TERR 1 AD QUEENS EE 73 R 80 2 G T East Sands HEPBURN GARDEN KI Community 7 NNE 5 Garden SSB 81 U L Botanic R N A R D N S S BUCHANAN GARDEN Garden GLAN T NS M E A DE D 82 R U R A S N Y G E R N UR V D S T 83 PB A R E VENU E 6 H A E S N E SO E T AT OA W B Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2010 . -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

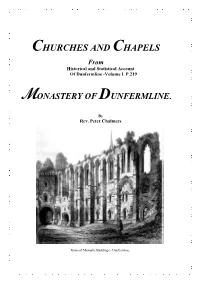

Churches and Chapels Monastery

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline -Volume I. P.219 MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. By Rev. Peter Chalmers Ruins of Monastic Buildings - Dunfermline. A REPRINT ON DISC 2013 ISBN 978-1-909634-03-9 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE FROM Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers, A.M. Minister of the First Charge, Abbey Church DUNFERMLINE. William Blackwood and Sons Edinburgh MDCCCXLIV Pitcairn Publications. The Genealogy Clinic, 18 Chalmers Street, Dunfermline KY12 8DF Tel: 01383 739344 Email enquiries @pitcairnresearh.com 2 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers The following is an Alphabetical List of all the Churches and Chapels, the patronage which belonged to the Monastery of Dunfermline, along, generally, with a right to the teinds and lands pertaining to them. The names of the donors, too, and the dates of the donation, are given, so far as these can be ascertained. Exact accuracy, however, as to these is unattainable, as the fact of the donation is often mentioned, only in a charter of confirmation, and there left quite general: - No. Names of Churches and Chapels. Donors. Dates. 1. Abercrombie (Crombie) King Malcolm IV 1153-1163. Chapel, Torryburn, Fife 11. Abercrombie Church Malcolm, 7th Earl of Fife. 1203-1214. 111 . Bendachin (Bendothy) …………………………. Before 1219. Perthshire……………. …………………………. IV. Calder (Kaledour) Edin- Duncan 5th Earl of Fife burghshire ……… and Ela, his Countess ……..1154. V. Carnbee, Fife ……….. ………………………… ……...1561 VI. Cleish Church or……. Malcolm 7th Earl of Fife. -

A4 Paper 12 Pitch with Para Styles

REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT 1983 NOTICE OF CHANGES OF POLLING PLACES within Fife’s Scottish Parliamentary Constituencies Fife Council has decided, with immediate effect to implement the undernoted changes affecting polling places for the Scottish Parliamentary Election on 6th May 2021. The premises detailed in Column 2 of the undernoted Schedule will cease to be used as a polling place for the polling district detailed in Column 1, with the new polling place for the polling district being the premises detailed in Column 3. Explanatory remarks are contained in Column 4. 1 2 3 4 POLLING PREVIOUS POLLING NEW POLLING REMARKS DISTRICT PLACE PLACE Milesmark Primary Limelight Studio, Blackburn 020BAA - School, Regular venue Avenue, Milesmark and Rumblingwell, unsuitable for this Parkneuk, Dunfermline Parkneuk Dunfermline, KY12 election KY12 9BQ 9AT Mclean Primary Baldridgeburn Community School, Regular venue 021BAB - Leisure Centre, Baldridgeburn, unavailable for this Baldridgeburn Baldridgeburn, Dunfermline Dunfermline KY12 election KY12 9EH 9EE Dell Farquharson St Leonard’s Primary 041CAB - Regular venue Community Leisure Centre, School, St Leonards Dunfermline unavailable for this Nethertown Broad Street, Street, Dunfermline Central No. 1 election Dunfermline KY12 7DS KY11 3AL Pittencrieff Primary Education Resource And 043CAD - School, Dewar St, Regular venue Training Centre, Maitland Dunfermline Crossford, unsuitable for this Street, Dunfermline KY12 West Dunfermline KY12 election 8AF 8AB John Marshall Community Pitreavie Primary Regular -

Doing the Lambeth Walk

DOING THE LAMBETH WALK The request We, the Bishops, Clergy and Laity of the Province of Canada, in Triennial Synod assembled, desire to represent to your Grace, that in consequence of the recent decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the well-known case respecting the Essays and Reviews, and also in the case of the Bishop of Natal and the Bishop of Cape Town, the minds of many members of the church have been unsettled or painfully alarmed; and that doctrines hitherto believed to be scriptural, undoubtedly held by the members of the Church of England and Ireland, have been adjudicated upon by the Privy Council in such a way as to lead thousands of our brethren to conclude that, according to this decision, it is quite compatible with membership in the Church of England to discredit the historical facts of Holy Scripture, and to disbelieve the eternity of future punishment1 So began the 1865 letter from the Canadians to Charles Thomas Longley, Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England. The letter concluded In order, therefore, to comfort the souls of the faithful, and reassure the minds of wavering members of the church, … we humbly entreat your Grace, …to convene a national synod of the bishops of the Anglican Church at home and abroad, who, attended by one or more of their presbyters or laymen, learned in ecclesiastical law, as their advisers, may meet together, and, under the guidance of the Holy Ghost, take such counsel and adopt such measures as may be best fitted to provide for the present distress in such synod, presided over by your Grace.