Andrew Leggett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

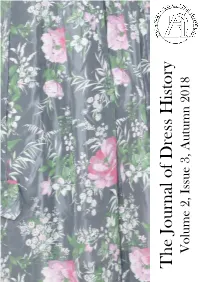

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

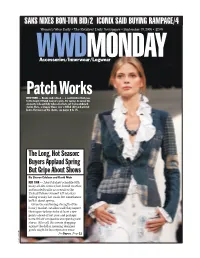

Patch Works NEW YORK — Rustic and Refined — a Combination That Goes to the Heart of Ralph Lauren’S Work

SAKS NIXES BON-TON BID/2 ICONIX SAID BUYING RAMPAGE/4 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 19, 2005 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Patch Works NEW YORK — Rustic and refined — a combination that goes to the heart of Ralph Lauren’s work. For spring, he mixed the elements in beautifully tailored jackets cut from patchwork denim. Here, a shapely blazer over a frilled shirt and printed jeans. For more on the shows, see pages 6 to 15. The Long, Hot Season: Buyers Applaud Spring But Gripe About Shows By Sharon Edelson and David Moin NEW YORK — A brutal show schedule with many off-site venues; hot, humid weather, and snarled traffic as a result of the United Nations summit left retailers feeling cranky last week, but nonetheless bullish about spring. Given the continuing strength of the luxury market, retailers said they expect their open-to-buys to be at least a few points ahead of last year and perhaps more if their companies are opening new stores. After all, the euro is dropping against the dollar, meaning designer goods might be less expensive come See Buyers, Page12 PHOTO BY JOHN AQUINO PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2005 WWD.COM Saks Turns Down Bon-Ton By Vicki M. Young WWDMONDAY Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear NEW YORK — Saks Inc. has re- jected a bid by The Bon-Ton Stores for its northern depart- FASHION Ralph Lauren presented an array of stunning items, Donna Karan offered ment store group, and will now elegant sensuality and Gwen Stefani made her runway debut to close the week. -

Private Lessons a Photo Story by Andrea Slip

Private Lessons A photo story by Andrea Slip 1 | P a g e Lesson01 Mike was a little nervous as he stood outside the brown front door on a Sunday afternoon. His mum had arranged for him to have some A-level revision lessons with a Miss Loren, a friend of hers who used to be a maths teacher. He didn’t quite know what to expect. He knocked on the door. Within a few moments the door opened. Mike had to try very, very hard not to let his jaw hit the floor. A lady opened the door to Mike. “You must be Mike, pleased to meet you, do come in, I am Sophie Loren” said Sophie shaking his hand. Mike recovered as he stared in amazement at the lady dressed in a cream silk dress. As she put her brown high heels on the step her button up dress split at the front to reveal both a cream lace edged slip and possibly the hint of a lacy stocking top. Miss Loren, Sophie, looked vaguely familiar, but he couldn’t quite place where from. 2 | P a g e Lesson02 Earlier that Sunday Sophie was dressing in her bedroom. She remembered that this afternoon that the son of her co-worker Alison was coming round for his first maths revision lesson. She had also established with Alison in the staffroom at work that he was the shelf stacker that had seen her up- skirt flash and had “helped” her find the toilet when her skirt had accidently fallen down at the Supermarket. -

A Study on the Characteristics of 20Th Century Womenfs Undergarments

IJCC, Vol. 6, No. 2, 83 〜92(2003) 15 A Study on the Characteristics of 20th Century Womenfs Undergarments Seo-Hee Lee and Hyeon-Ju Kim* Assistant Professor, Dept, of Fashion and Beauty, Konyang University Instructor, Dept, of Clothing Science, Seoul Women's University* (Received June 23, 2003) Abstract This study aims to classify -women's undergarments of the 20th century by periods, and to examine their characteristics. The research method consists of a literature study based on relevant documentary records and a demonstrative analysis of graphic data collected from each reference. The features of women's under garments obtained from the study are as fallows: First, silhouette changes of outer garments appear to influence the type and style of a new undergarment. Second, technological development results in a new type of undergarments. Third, the development of new material appears to influence functions and design of undergarments. Fourth, social changes including the development of sports affects the changes of undergarments. As seen so far, the form or type, material, and color in undergarment diversify when fashion changes become varied and rapid. As shown before the 20th century, the importance of undergarment's type, farm, and function gradually reduces according to the changes of -women's mind due to their social participation, although it still plays a role in correcting the shape of an outer garment based on the outer silhouette. The design also clearly shows the extremes of maximization and minimization of decoration. Key words : undergarment, modern fashion, lingerie, infra apparel the beginning of the 20th century, corsets and I. -

Mum's Lingerie Draw

Mum's Lingerie Draw Mike was profoundly affected by the lady who flashed her slip, sheer stockings and nylon panties at him in the Supermarket. He had to find out more and he started his research at home, in his Mum's lingerie draw. A photo story by Andrea Slip [email protected] 1 | P a g e mum01 It was wrong, just so wrong. He felt ashamed. It was so wrong it was probably illegal. What would his Mum say? Why had he done it? They had looked so pretty sitting there. He swore he would never do it again. Mike lived with his Mum. His Dad had walked out 5 years earlier, he wasn't missed. Mike got on well with his Mum, they were very alike. As he ran his bath he stripped off his clothes and contemplated a quick wank whilst he waited but needed something to get him started. His eyes fell on the overfull laundry basket. Right on top were a pair of his Mum's navy blue nylon panties. They looked so pretty with a lacy hem. His resistance to touching his Mum's undies held him back for oh, I don' know, about a nano second maybe. 2 | P a g e Mum02 He picked up the panties and examined them. This was the first time he had ever touched his Mum's underwear, no not underwear, her lingerie. So French, so much a sexier a word than underwear or even pants, although panties was nice as well but perhaps a bit American. -

M&S: Lingerie

M&S: Lingerie Providing secret support since 1926 1926 We introduced our first bras, designed to suit the ideal of a flatter chest and boyish figure, fashions that were all the rage in the 1920s. As well as bras we sold garters, directoire knickers, sanitary belts and free-run bodices. White cotton and rayon bra, 1920s Ref: T81/18 1932 We sold corsetry and uplifting brassieres advertised with the slogan ‘A perfect figure guaranteed’. These new styles suited the changing trend for ‘lift and separation’. Advert from ‘The Marks and Spencer Magazine’, Christmas 1932 1941-1945 All clothing during the war had to adhere to Utility standards, due to the shortages posed by wartime conditions. Clothing had to meet the Government’s regulations, and we developed a Utility lingerie range that was not only functional but attractive. Satin bra with Utility label, c1943 Ref: T1941/5 1951-1953 We developed our bra sizes to include three cup sizes; small, medium and large. This was inspired by American lingerie and allowed the bras to fit a greater proportion of women. In 1953 we sold 125,000 brassieres per week. Advert showing range of bra sizes, St Michael News, 1953 St Michael News, Jan 1958 1953 We started selling bras aimed at teenagers and younger women. Light, simple styles such as the brief brassiere were designed for the more ‘youthful figure’. In 1953 we sold 25% of the nation’s total sales in knitted vests. Women’s knitted vests were only available in two sizes; medium and large. St Michael News, Sep 1958 1955 We sold elastic high line girdles, which provided more support, and ensured ‘spare tyres, [and] ungainly bulges are eliminated’. -

Lingerie Providing Secret Support Since 1926 1926 We Opened Our Drapery Department, Which Included Clothing As Well As Lingerie

M&S: Lingerie Providing secret support since 1926 1926 We opened our Drapery Department, which included clothing as well as lingerie. Our first bras were designed to provide the flatter chest and boyish figure popular at the time. Our lingerie range included garters, directoire knickers, sanitary belts and free- run bodices. The oldest bra in the Archive collection dates from the late 1920s – it offered a low level of support whilst giving the wearer a smooth silhouette. White cotton and rayon bra, c1928, Ref: T81/18 Window display of artificial silk lingerie, 1937 1930s The most popular fabric for lingerie during the 1930s and 1940s was artificial silk, or rayon as it was known - an early synthetic fibre made with cellulose from wood pulp. The fabric was seen as a more affordable alternative to silk, and a more luxurious option than cotton, linen or wool. 1932 We sold corsetry and uplifting brassieres advertised with the slogan ‘A perfect figure guaranteed’. These new styles suited the changing trend for ‘lift and separation’. Hook-sided girdles gave ‘that slim silhouette demanded by present fashions’. Advert from ‘The Marks and Spencer Magazine’, 1932 1939 Stock control documents show that by 1939 we were selling at least 30 styles of bras – most were available in white or peach, sometimes blue. Styles included ‘rubber reducing brassieres’ and an Outsize range Advert from ‘The Marks and Spencer Magazine’, 1932 1941-1945 During the war, austerity measures and the Utility Scheme meant designers had to work harder to continue making attractive yet practical garments. Despite this, we were still able to produce glamorous lingerie. -

Stockings Review

Stockings Review Andrea reviews some new stockings by Gabriella and shows how they should be worn. (with apologies to Legslavish on You Tube for the idea) 1 | P a g e Today I am going to review some stockings called Calze, Elite by Gabriella (a Polish stocking manufacturer). I bought these on Ebay, so this is an independent review. Eyes on the stockings packet please, not my creamy satin night shirt or my lacy nylon slip. 2 | P a g e The stockings are 20 denier, not as thin as some sheer stockings I wear. The colour is Nero (black) and the size ¾ (large). What is not obvious from the packet is that these are hold ups. The cost was about £6 from Aurelliecom on Ebay,with free 1st class delivery, excellent deal, as I saw them at a higher price on Amazon. 3 | P a g e So let’s take the stockings out of the lovely packet. I should keep packets like this as the images are so lovely. 4 | P a g e As with most modern stockings there is a large lycra content so the stockings look quite short and very opaque straight out of the packet. 5 | P a g e I am going to try the stockings on but will need to change out of the brown BHS lace top stockings I am already wearing. They don’t show this on Legslavish on You Tube so I hope you are not peeping at my pink French knickers as I raise my silky slip! 6 | P a g e You can just see the two bands of silicone at the top of the stockings, but not three, as with some British stockings. -

The Changing Gender-References of Words for Items of Clothing

The Changing Gender-references of Words for Items of Clothing Piia Kujanpää University of Tampere Faculty of Communication Sciences Master’s Programme in English Language and Literature Master’s Thesis May 2018 Tampereen yliopisto Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta Englannin kielen ja kirjallisuuden maisteriopinnot KUJANPÄÄ, PIIA: Vaatesanojen muuttuvat sukupuoliviittaukset Pro gradu -tutkielma, 72 sivua + liitteet 11 sivua Toukokuu 2018 ________________________________________________________________________________ Sukupuoli kulttuurisena konstruktiona (gender) on muuttuva ja rakentuu sosiaalisessa vuorovaikutuksessa myös kielen kautta. Näin ollen myös sukupuoli, johon vaatesana viittaa voi muuttua. Tämän tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää tätä aiemmin vähän tutkittua aluetta. Tutkimuskysymykset ovat seuraavat: 1) Miten ja miksi vaatesanojen sukupuoliviittaukset ovat muuttuneet Norrin (1996, 1998) tutkimuksista? 2) Tukeeko myös korpusaineisto kahdesta korpuksesta (The British National Corpus (BNC) ja The Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWbE)) Norrin (1998) tutkimuksessaan esittelemiä viittä sukupuoliviittausten muuttumisen vaihetta? 3) Onko Norrin viiden vaiheen malli sovellettavissa myös muihin vaatesanoihin? Tutkimus keskittyy vain brittienglantiin, jotta tulosten vertailu Norrin tutkimukseen olisi mahdollista. Tutkimus yhdistää sekä kvalitatiivisia että kvantitatiivisia tutkimusmenetelmiä. Tutkimuksen aineistona on seitsemän sanakirjaa ja korpusaineistona BNC ja GloWbE. BNC sisältää materiaalia 1990-luvun alkupuoliskolta, kuten -

Wedding Invitation

Wedding Invitation Brenda and Alan continue their relationship, after meeting at a private sewing class. One day, Brenda receives a wedding invitation from an old friend whose daughter Fifi is getting married. Brenda has to get a new frock, but what will Alan wear? 1 | P a g e “Oh look Alan, Fifi is getting married in September, we are both invited to the evening reception,” exclaimed Brenda as she opened the post. “What am I going to wear?” She looked again at the invitation, “I am going to have to get a new dress, I have nothing that fits the bill. Perhaps a dress with purple accents and matching shoes. “Who’s Fifi,” asked Alan? “Oh you must remember her Alan! She is Jo’s daughter, Jo was my best friend at school.” Alan wondered if it would a cross dressing wedding, he had always been jealous of the ladies all dressed up in their frillies at previous weddings. “But what am I going to wear,” asked Alan? “Oh I don’t know, the invite says pink or purple dress code. Perhaps you could wear your suit with a purple tie,” said Brenda vaguely. Alan frowned and would give it a think. 2 | P a g e Brenda did buy a new dress from Jacques Vert. She put it on the outside of the door of her wardrobe, so it would not become creased before she wore it for the wedding. Her wardrobe was bursting with clothes. Alan kept looking at it and thought how nice Brenda would look in. -

Bodywear Bodywear

EU MARKET SURVEY 2003 EU MARKET SURVEY 2003 BODYWEAR BODYWEAR Mailing address: P.O. Box 30009, 3001 DA Rotterdam, The Netherlands Phone: +31 10 201 34 34 Fax: +31 10 411 40 81 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cbi.nl CENTRE FOR THE PROMOTION OF IMPORTS FROM DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Office: WTC-Beursbuilding, 5th floor 37 Beursplein, Rotterdam, The Netherlands EU MARKET SURVEY 2003 BODYWEAR Compiled for CBI by: Drs. Jan P. Servaas May 2003 DISCLAIMER The information provided in this market survey is believed to be accurate at the time of writing. It is, however, passed on to the reader without any responsibility on the part of CBI or the authors and it does not release the reader from the obligation to comply with all applicable legislation. Neither CBI nor the authors of this publication make any warranty, expressed or implied, concerning the accuracy of the information presented, and will not be liable for injury or claims pertaining to the use of this publication or the information contained therein. No obligation is assumed for updating or amending this publication for any reason, be it new or contrary information or changes in legislation, regulations or jurisdiction. New CBI publication with updated contents replacing CBI’s EU Market Survey 2002 ‘Bodywear’ and CBI’s EU Strategic Marketing Guide 2002 ‘Bodywear’ (published in January 2002). Photo courtesy: Hunnink & van den Broek CONTENTS REPORT SUMMARY 7 INTRODUCTION 10 PART A: EU MARKET INFORMATION 1 PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 15 1.1 Product groups 15 1.2 Customs/statistical product -

The Lawyer (Part 2, the Funeral) by Andrea Slip

The Lawyer (part 2, the Funeral) by Andrea Slip 1 | P a g e Due to Covid and the high death toll it was another month before Mr Lewdanski’s funeral took place at Weybridge Crematorium. I had trouble deciding what to wear. I did not really want to go all out black as I knew that was what Wendy would be wearing. 2 | P a g e I decided to go with matching white panties, bra, suspenders, and a cute little white half-slip. 3 | P a g e Hosiery was sheer black stockings, of course, and black heels. 4 | P a g e I put on my black skirt and a new lacy white top. When I looked in the mirror, I realised just how thin the white blouse was. It was almost completely sheer except for some little white hearts. I thought that perhaps I should wear a camisole or a full slip to be more discrete and stop everyone staring at my lacy bra and boobs, although some men might quite like that view. 5 | P a g e I found a white camisole and tried that on. It looked much better, now everyone could stare at my lacy camisole instead but at least my cleavage would not show quite so much. I pulled my sheer blouse down over my camisole. 6 | P a g e As I adjusted my slip and stockings I wondered if Wendy was putting on her black slip and French knickers at the same time as me. 7 | P a g e As it turned out I was right.