An Interview with Khushwant Singh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ssc Special Daily Quiz -740 Total Questions-40, Time - 40 Minutes, Marks - 40 Arena of General Knowledge 1

DAILY QUIZ-740 (11.09.2019) TEST YOURSELF SSC SPECIAL DAILY QUIZ -740 TOTAL QUESTIONS-40, TIME - 40 MINUTES, MARKS - 40 ARENA OF GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. Which of the following is in liquid form at room temperature? (a) Cerium (b) Sodium (c) Francium (d) Lithium 2. Soda water contains (a) Nitrous Acid (b) Carbonic Acid (c) Carbon Dioxide (d) Sulphur Acid 3. Which of the following is not an isotope of hydrogen? (a) Protium (b) Yttrium (c) Deuterium (d) Trituim 4. Polythene is industrially prepared by the polymerization of (a) Methane (b) Styrene (c) Acetylene (d) Ethylene 5. Which of the following is not a chemical reaction? (a) Burning of Paper (b) Digestion of Food (c) Conversion of Water into Steam (d) Burning of Coal 6. What is condensation? (a) Change of Gas into Solid (b) Change of Solid into Liquid (c) Change of Vapour into Liquid (d) Change of Heat Energy into Cooling Energy 7. During the development of an embryo the formation of brain marks the beginning of organ formation. Eye in a vertebrate develops from midbrain. If after the formation of brain the mid brain is destroyed then what will be the resultant effect? (a) Total Failure of Eye Formation (b) Development of a Single Eye (c) Defective Development of Eyes (d) Absence of Vision in the Eyes 8. The artificial rearing of honey bees is called (a) Sylviculture (b) Sericulture (c) Apiculture (d) Lociculture 9. Pineapple is a (a) Single Fruit (b) Collection of Fruit (c) Stem of the Plant (d) Collection of Leaves 10. The disease trachoma is related to the (a) Eye (b) Ear (c) Mouth (d) Throat 11. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

Afrindian Fictions

Afrindian Fictions Diaspora, Race, and National Desire in South Africa Pallavi Rastogi T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss C O L U MB us Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rastogi, Pallavi. Afrindian fictions : diaspora, race, and national desire in South Africa / Pallavi Rastogi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0319-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0319-1 (alk. paper) 1. South African fiction (English)—21st century—History and criticism. 2. South African fiction (English)—20th century—History and criticism. 3. South African fic- tion (English)—East Indian authors—History and criticism. 4. East Indians—Foreign countries—Intellectual life. 5. East Indian diaspora in literature. 6. Identity (Psychol- ogy) in literature. 7. Group identity in literature. I. Title. PR9358.2.I54R37 2008 823'.91409352991411—dc22 2008006183 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–08142–0319–4) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–08142–9099–6) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Typeset in Adobe Fairfield by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction Are Indians Africans Too, or: When Does a Subcontinental Become a Citizen? 1 Chapter 1 Indians in Short: Collectivity -

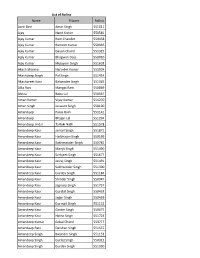

Name Fname Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor

List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor 550581 Ajay Kumar Ram Chander 550458 Ajay Kumar Ramesh Kumar 550336 Ajay Kumar Gayan Chand 551315 Ajay Kumar Bhagwan Dass 550010 Ajay Kumar Mulayam Singh 551603 Akash Sharma Narinder Kumar 551904 Akashdeep Singh Pal Singh 551414 Akashpreet Kaur Balwinder Singh 551365 Alka Rani Mangat Ram 550869 Alvina Babu Lal 550561 Aman Kumar Vijay Kumar 551270 Aman Singh Jaswant Singh 550190 Amandeep Paras Ram 551141 Amandeep Bhajan Lal 551294 Amandeep Jindal Tarloki Nath 551578 Amandeep Kaur Jarnail Singh 551871 Amandeep Kaur Harbhajan Singh 550169 Amandeep Kaur Sukhmander Singh 550781 Amandeep Kaur Manjit Singh 551490 Amandeep Kaur Sarbjeet Singh 551677 Amandeep Kaur Jasraj Singh 551491 Amandeep Kaur Sukhwinder Singh 551300 Amandeep Kaur Gurdev Singh 551184 Amandeep Kaur Shinder Singh 550347 Amandeep Kaur Jagroop Singh 551737 Amandeep Kaur Gurdial Singh 550453 Amandeep Kaur Jagsir Singh 550459 Amandeep Kaur Gurmail SIngh 551122 Amandeep Kaur Ginder Singh 550675 Amandeep Kaur Natha Singh 551724 Amandeep Kumar Gokal Chand 550777 Amandeep Rani Darshan Singh 551537 Amandeep Singh Baljinder Singh 551153 Amandeep Singh Gurtej Singh 550312 Amandeep Singh Gurdev Singh 551030 List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Amandeep Singh Balwinder SIngh 550016 Amandeep Singh Surjeet Singh 551251 Amandeep Singh Subhash Singh 551637 Amandeep Singh Angraj Singh 551622 Amandeep Singh Gurcharan Singh 551596 Amandeep Singh Nathu Ram 550748 Amandeep Singh Jarnail Singh 550058 Amandeep Singh Shinder -

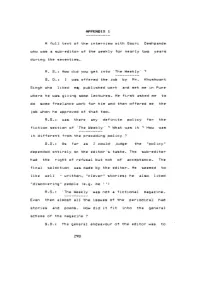

APPENDIX 1 a Full Text of the Interview with Gauri Deshpande Who Was A

APPENDIX 1 A full text of the interview with Gauri Deshpande who was a sub-editor of the weekly for nearly two years during the seventies. R. S.: How did you get into The Weekly' ? G. D.: I was offered the job by Mr. Khushwant Singh who liked m«y published work and met me in Pune where he was giving some lectures. He first asked me to do some freelance work for him and then offered me the job when he approved of that too. R.S.: was there any definite policy for the fiction section of "The Weekly' ? What was it ? How was it different from the preceding policy ? B.D.: As far as I could judge the "policy" depended entirely on the editor's taste. The sub-editor had the right of refusal but not of acceptance. The final selection was made by the editor. He seemed to like well - written, "clever" stories; he also liked "discovering" people (e.g. me II) R.S.: 'The Weekly' was not a fictional magazine. Even then almost all the issues of the periodical had stories and poems. How did it fit into the general scheme of the magazine ? G.D.: The general endeavour of the editor was to 298 make 'The Weekly' into a brighter, more popular, more accessible paper; less 'colonial' if one can say that. The changes he made in typography, layout, covers, photographs, even payment scales, all point to this. The often controversial themes of his main photo features (e.g. communities of india) and the bright new look fiction were part of the general policy. -

The Partition of India Midnight's Children

THE PARTITION OF INDIA MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN, MIDNIGHT’S FURIES India was the first nation to undertake decolonization in Asia and Africa following World War Two An estimated 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of India Partition saw the largest migration of humans in the 20th Century, outside war and famine Approximately 83,000 women were kidnapped on both sides of the newly-created border The death toll remains disputed, 1 – 2 million Less than 12 men decided the future of 400 million people 1 Wednesday October 3rd 2018 Christopher Tidyman – Loreto Kirribilli, Sydney HISTORY EXTENSION AND MODERN HISTORY History Extension key questions Who are the historians? What is the purpose of history? How has history been constructed, recorded and presented over time? Why have approaches to history changed over time? Year 11 Shaping of the Modern World: The End of Empire A study of the causes, nature and outcomes of decolonisation in ONE country Year 12 National Studies India 1942 - 1984 2 HISTORY EXTENSION PA R T I T I O N OF INDIA SYLLABUS DOT POINTS: CONTENT FOCUS: S T U D E N T S INVESTIGATE C H A N G I N G INTERPRETATIONS OF THE PARTITION OF INDIA Students examine the historians and approaches to history which have contributed to historical debate in the areas of: - the causes of the Partition - the role of individuals - the effects and consequences of the Partition of India Aims for this presentation: - Introduce teachers to a new History topic - Outline important shifts in Partition historiography - Provide an opportunity to discuss resources and materials - Have teachers consider the possibilities for teaching these topics 3 SHIFTING HISTORIOGRAPHY WHO ARE THE HISTORIANS? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF HISTORY? F I E R C E CONTROVERSY HAS RAGED OVER THE CAUSES OF PARTITION. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Static GK Capsule 2017

AC Static GK Capsule 2017 Hello Dear AC Aspirants, Here we are providing best AC Static GK Capsule2017 keeping in mind of upcoming Competitive exams which cover General Awareness section . PLS find out the links of AffairsCloud Exam Capsule and also study the AC monthly capsules + pocket capsules which cover almost all questions of GA section. All the best for upcoming Exams with regards from AC Team. AC Static GK Capsule Static GK Capsule Contents SUPERLATIVES (WORLD & INDIA) ...................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST EVER(WORLD & INDIA) .............................................................................................................................. 5 WORLD GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................ 9 INDIA GEOGRAPHY.................................................................................................................................................. 14 INDIAN POLITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 32 INDIAN CULTURE ..................................................................................................................................................... 36 SPORTS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

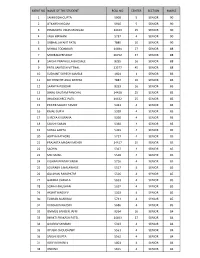

Merit No Name of the Student Roll No Center Section Marks

MERIT NO NAME OF THE STUDENT ROLL NO CENTER SECTION MARKS 1 SAMRIDDH GUPTA 5908 5 SENIOR 90 2 UTKARSH NIGAM 5916 5 SENIOR 90 3 HIMANSHU VIKAS MUNGAJI 14423 25 SENIOR 90 4 YASH HIRWANI 5737 4 SENIOR 90 5 SNEHAL JAYANT PATIL 7880 10 SENIOR 90 6 MIHIKA TODANKAR 14694 27 SENIOR 88 7 MOREAJAYBHARAT 26752 37 SENIOR 88 8 SAKSHI PRAPHULLA BHOSALE 9255 16 SENIOR 88 9 PATIL SANTOSH VITTHAL 23577 45 SENIOR 88 10 SUSHANT SURESH KAMBLE 1601 1 SENIOR 86 11 DR CHINCHE ANUJ DEEPAK 7887 10 SENIOR 86 12 SAANIYA PODDAR 9253 16 SENIOR 86 13 BINAL GAUTAM PANCHAL 14428 25 SENIOR 85 14 BHAGYASHREE PATIL 14432 25 SENIOR 85 15 PRATIK SANJAY TAMBE 5331 4 SENIOR 85 16 KAJAL GUP A 5328 4 SENIOR 85 17 SHREYA KHURANA 5326 4 SENIOR 85 18 SAKSHI SARAN 5330 4 SENIOR 85 19 SONAL GUPTA 5329 4 SENIOR 85 20 ADITYA RATHORE 5727 4 SENIOR 85 21 PRAJAKTA MADAN MEHER 14417 25 SENIOR 85 22 SACHIN 5327 4 SENIOR 85 23 MD ISMAIL 5528 4 SENIOR 85 24 VIDHAN PRATAP SINGH 5726 4 SENIOR 85 25 SOURABH S NALAWADE 5527 4 SENIOR 85 26 GULSHAN BARAPATRE 5526 4 SENIOR 85 27 GARIMA CHAWLA 5653 4 SENIOR 85 28 SONALI BHUSHAN 5652 4 SENIOR 85 29 AKSHIT NAGDEV 5363 4 SENIOR 85 30 TUSHAR AGARWAL 5731 4 SENIOR 85 31 VANSHIKA BHASIN 5686 4 SENIOR 85 32 UMMUL BANEEN JAFRI 9264 16 SENIOR 84 33 BHAKTI PRAKASH PATEL 14693 27 SENIOR 84 34 GAURAV SHARMA 5363 4 SENIOR 84 35 AYUSHI CHOUDHARY 5561 4 SENIOR 84 36 SAKSHI GUPTA 5562 4 SENIOR 84 37 ADITYA KHANTE 5801 4 SENIOR 84 38 ANJANA 5655 4 SENIOR 84 39 DISHIP KASHYAP 5911 5 SENIOR 83 40 PRANJAL TRIPATHI 9248 16 SENIOR 83 41 SHARATH S ANCHATAGERI 9355 17 SENIOR -

S.No. Name Date of Birth Qualifica- Tion Last Post Held Present Address State/ Country Telephone No. Valid Upto 1 V

S.No. Name Date of Qualifica- Last Post Present Address State/ Telephone No. Valid upto Birth tion Held Country 1 V. Ravindranath 03.09.1948 B.Sc. Engg. Chief Flat 001, C.R. Towers, Andhra 9110320236 Sep/22 (Civil) Engineer Gandhipuram-1, Pradesh 9346238341 (Retd.), Rajahmundry, Govt. of East Godavari Distt., Andhdra Andhra Pradesh- Pradesh 500103 2 Toli Basar 07.05.1960 B.E. (Civil), Chief Mowb-II, Q-7, T-V, Near Arunachal 9436257734 Feb-20 L.L.B. Engineer, Chief Engineer Office, Pradesh 9436895180 Highway, PWD, PO/PS: 0360-2211418 Govt of Itanagar, Arunachal Dist. Papumpare, Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh- 791111 3 A.C. Bordoloi 13.01.1957 B.E. (Civil), Commissioner House No.28, Assam 9435012873 Mar-23 M.E. (Civil) & Spl. Dr. Zakir Hussain Road, 9101224005 Secretary Sarumotoria, Guwahati- 0361-2354292 (Retd.), PWD, 781036 Govt. of Assam 4 Bani Kanta Das 02.03.1956 B.E. (Civil), Secretary H.No.33, Kundil Nagar, Assam 9678073112 May-20 LLB (Retd.), PWD, Basistha Charial, 9864209436 Govt. of P.O. Basiatha, Assam Guwahati-781029 5 Maheswar Pathak 01.08.1947 B.Tech. Secretary House No.50, Upaasaa Assam 9101821399 Aug-23 (Hons.) (Retd.), PWD, Pub-Sarania, Govt. of P.O. Silpukhui, Assam Guwahati-781003 6 M.K. Sinha 01.07.1956 B.Sc. Engg. Chief B-17, Bankmen's Bihar 9973081347 May-21 (Civil) Engineer Colony, (Retd.), Chitragupt Nagar, R.C.D., Patna-800020 Govt. of Bihar Page 1 7 Ram Awadhesh 15.01.1958 B.Sc. Engg. Chief Adarsh Path No.4, Bihar 8709740931 Jan-22 Kumar (Civil) Engineer Professor's Colony, 9431022751 (Retd.), Near Lal Babu Market, R.C.D., North Shastri Nagar, Govt. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt.