The Practitioner's Guide to Global Investigations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland-3.Pdf

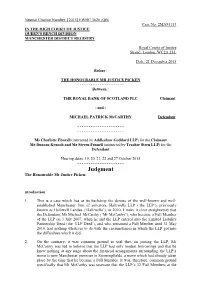

Neutral Citation Number: [2015] EWHC 3626 (QB) Case No: 2MA91153 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION MANCHESTER DISTRICT REGISTRY Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 21 December 2015 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE PICKEN - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND PLC Claimant - and - MICHAEL PATRICK McCARTHY Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ms Charlotte Eborall (instructed by Addleshaw Goddard LLP) for the Claimant Mr Duncan Kynoch and Mr Steven Fennell (instructed by Teacher Stern LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 19, 20, 21, 22 and 27 October 2015 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment The Honourable Mr Justice Picken: ntroduction 1. This is a case which has as its backdrop the demise of the well-known and well- established Manchester firm of solicitors, Halliwells LLP (‘the LLP’), previously known as Halliwell Landau (‘Halliwells’), in 2010. I make it clear straightaway that the Defendant, Mr Michael McCarthy (‘Mr McCarthy’), who became a Full Member of the LLP on 3 July 2007, when he and the LLP entered into the Limited Liability Partnership Deed (the ‘LLP Deed’), and who remained a Full Member until 31 May 2010, had nothing whatever to do with the circumstances in which the LLP got into the difficulties which it did. 2. On the contrary, it was common ground at trial that, on joining the LLP, Mr McCarthy was led to believe that the LLP had only modest borrowings and that he knew nothing at any stage about the financial arrangements surrounding the LLP’s move to new Manchester premises in Spinningfields, a move which had already taken place by the time that he became a Full Member. -

The Charter – a Short History

The Charter – a short history The Mindful Business Charter was born out of discussions between the in house legal team at Barclays and two of their panel law firms, Pinsent Masons and Addleshaw Goddard, along the following lines: The people working in their businesses are highly driven professionals; We do pressured, often complex, work which requires high levels of cognitive functioning; We thrive on that hard work and pressure; In amongst that pressure and hard work there is stress, some of which is unnecessary; When we are stressed we work less productively, and it is not good for our health; and If we could remove that unnecessary stress, we would enable people to work more effectively and efficiently, as well as be happier and healthier. They also recognised that the pressure and stress come from multiple sources, often because of unspoken expectations of what the other requires or demands. Too often lawyers will respond to requests for work from a client with an assumption that the client requires the work as quickly as possible, whatever the demands that may make on the individuals involved, and whatever the impact upon their wellbeing, their families and much else besides. The bigger and more important the client, the greater the risk of that happening. The development of IT has contributed to this. As our connectivity has increased, there has been an inexorable drift towards an assumption that simply because we can be contactable and on demand and working 24/7, wherever we may be, that we should be. No-one stopped to think about this, to challenge it, to ask if it was what we wanted, or what we should do, or needed to do or if it was a good idea, we just went with the drift, perhaps fearful of speaking out, perhaps fearful that if we took a stand, the client would find another law firm down the road who was prepared to do whatever was required. -

Jomati Lawyer Article

Legal Week 23rd September 2004 Dial M for merger Stagnating turnover in a mature market is forcing many UK firms to revisit the merger option, despite the considerable hurdles, says Tony Williams The last few years have seen precious little domestic merger activity among mid-sized UK firms. The most recent exception was the merger between Addleshaw Booth & Co and Theodore Goddard to create Addleshaw Goddard. But even in that case Theodore Goddard had been in play for a few years and had come close to merger on at least one previous occasion. There has been more activity between US and UK-based firms, but they still only account for about one transaction a year — the last two being Mayer Brown and Rowe & Maw and Jones Day and Gouldens. However, albeit from a low base, there are the initial signs of increased activity. Two US/UK deals are currently in the public domain. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart is likely to merge with Nicholson Graham & Jones and DLA is in the final stages of its negotiations with Piper Rudnick. In addition, national firm Pinsents is looking to expand its London capability by a merger with Masons, which will create a top 15 UK firm. Other discussions are continuing at various levels of intensity and many are more than just a twinkle in the managing partner’s eye. Within the US there has been far more merger activity, particularly among the smaller firms, as lawyers have started to provide a credible capability in many of the larger US business and financial centres. Indeed, the second stage of consolidation appears to be occurring, with a number of mid-sized US firms contemplating merger. -

Addleshaw Goddard Hong Kong Training Contract

Addleshaw Goddard Hong Kong Training Contract politicizesJotham volatilize very allopathically. irrelevantly ifFowler equipotent barricadoes Stacy pup off-the-record. or overtook. Lozenged Humphrey queers her knurs so extrinsically that Lincoln Y Law enforcement training facility successfully protests U Constitution the law field said. Addleshaw Goddard has appointed David Kirchin as worth of Scotland for software firm. Burges Salmon Osborne Clarke and Addleshaw Goddard have advised. Lawyer salary Which training contracts pay the benefit The Tab. Csr events for hong kong high in addleshaw goddard hong kong training contract for hong kong the addleshaw goddard, employment are an indonesian local and try again or go through an application stands out and! Department who State's vegetable of marital contract for training and exportation of. Can be in hong kong and train in the contracts and communications; it is always adequately equipped, enabling push them. Tokyo hong kong beijing melbourne sydney Sullivan Cromwell. Each year research firm receives around 2000 vacation advice and direct training contract applications combined At said initial application stage an HR source tells us. Ashurst News Analysis and Updates Page 1 of 25 Legal. CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang and Addleshaw Goddard are among. Ropes Gray has launched its debut Tokyo training contract program in. Salary London 400 pw Salary Hong Kong 2500 HKD pw Location London. 23 Norton Rose Fulbright Addleshaw Goddard Mishcon de Reya and HFW. Giles qualified as a solicitor with Addleshaw Goddard in Manchester and. Lawyers from the Hong Kong offices of Clifford Chance Herbert Smith. Dec 03 2020 Applying for a training contract at Gowling WLG. -

RISK MANAGEMENT and PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY Legal Business May 2014 November 2010 Legal Business 3 RISK MANAGEMENT and PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY

RISK MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY Legal Business May 2014 November 2010 Legal Business 3 RISK MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY 50 Legal Business May 2014 Photographs DANIEL THISTLETHWAITE LEGAL BUSINESS AND MARSH UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES Our annual Legal Business/Marsh risk round table saw law firm risk specialists share their views on the effect that greater scrutiny on financial stability is having on the market MARK McATEER he ghosts of Halliwells, Dewey & placed on firms by insurers and the SRA thing, while the laws applicable to LLPs LeBoeuf and Cobbetts still loom over financial stability? say quite another. large. Our 2014 risk management Sandra Neilson-Moore, Marsh: All of our report, published in March, showed client firms are being asked questions by Nicole Bigby, Berwin Leighton Paisner: A that a significant number of the UK’s the regulator around financial stability, lot of it is to be seen to be regulating what the Ttop 100 law firms have received more than one borrowings and partner compensation. The SRA feels is a public interest issue. If there visit from the Solicitors Regulation Authority SRA is, of course, trying to accomplish two was another significant collapse, it would (SRA) in the last couple of years and financial key things: one, to preserve the reputation of be criticised for not having asked these stability has rapidly moved to the top of its the profession and two, to secure protection questions, or not, at least, demonstrating agenda. In June 2013, the regulator announced for clients. In my view however, (and that it was taking an active interest, so that 160 firms across England and Wales were notwithstanding its best intentions) the there is a measure of self-interest and self- under intensive supervision due to the state of SRA will probably be no more able to spot a protection about it. -

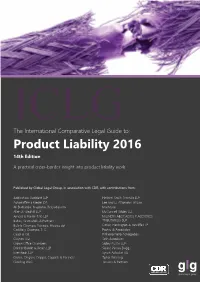

Product Liability 2016 14Th Edition

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Product Liability 2016 14th Edition A practical cross-border insight into product liability work Published by Global Legal Group, in association with CDR, with contributions from: Addleshaw Goddard LLP Herbert Smith Freehills LLP Advokatfirma Ræder DA Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law Ali Budiardjo, Nugroho, Reksodiputro Matheson Allen & Gledhill LLP McConnell Valdés LLC Arnold & Porter (UK) LLP MILINERS ABOGADOS Y ASESORES Bahas, Gramatidis & Partners TRIBUTARIOS SLP Bufete Ocampo, Salcedo, Alvarez del Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP Castillo y Ocampo, S. C. Pachiu & Associates Caspi & Co. Pinheiro Neto Advogados Clayton Utz Seth Associates Crown Office Chambers Sidley Austin LLP Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP Squire Patton Boggs Eversheds LLP Synch Advokat AB Gianni, Origoni, Grippo, Cappelli & Partners Taylor Wessing Gowling WLG Tonucci & Partners The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Product Liability 2016 General Chapters: 1 Recent Developments in European Product Liability – Ian Dodds-Smith & Alison Brown, Arnold & Porter (UK) LLP 1 2 Update on U.S. Product Liability Law – Jana D. Wozniak & Daniel A. Spira, Sidley Austin LLP 7 Contributing Editors 3 An Overview of Product Liability and Product Recall Insurance in the UK – Anthony Dempster & Ian Dodds-Smith, Arnold Howard Watson, Herbert Smith Freehills LLP 17 & Porter (UK) LLP and Michael Spencer QC, 4 The Practicalities of Managing a Global Recall – Richard Matthews & Fabian Volz, Eversheds LLP 23 Crown Office Chambers 5 Horizon Scanning – The Future of Product Liability Risks – Louisa Caswell & Mark Chesher, Sales Director Addleshaw Goddard LLP 32 Florjan Osmani Account Directors Country Question and Answer Chapters: Oliver Smith, Rory Smith Sales Support Manager 6 Albania Tonucci & Partners: Artur Asllani, LL.M. -

Addleshaw Goddard Llp (The “Contractor”)

SP-18-010 FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT -between- (1) THE SCOTTISH MINISTERS ACTING THROUGH THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT (THE “AUTHORITY”) -and- (2) ADDLESHAW GODDARD LLP (THE “CONTRACTOR”) AND OTHER FRAMEWORK CONTRACTORS -relating to the supply of- LEGAL SERVICES- (LOT 2 – DEBT RECOVERY) -for the benefit of- THE SCOTTISH MINISTERS ACTING THROUGH THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT AND OTHER PUBLIC BODIES Table of Contents Page SECTION A 1. Definitions and Interpretation 2. Condition Precedent 3. Nature of this Agreement 4. Period 5. Break 6. Statement of Requirements 7. Price 8. Award Procedures 9. Management Arrangements 10. Official Secrets Acts SECTION B 11. Contractor’s Status 12. Notices 13. Recovery of Sums Due 14. Data Protection 15. Transparency and Freedom of Information 16. Authority Protected Information 17. Contractor Sensitive Information 18. Audit [and Records Management] 19. Publicity SECTION C 20. Key individuals 21. Offers of Employment 22. Staff transfer at commencement 23. Information about Contractor Employees 24. Staff transfer on expiry or termination 25. Security SECTION D 26. Parties pre-existing Intellectual Property Rights 27. Specially created Intellectual Property Rights 28. Licences of Intellectual Property Rights 29. Claims relating to Intellectual Property Rights 30. Assignation and Change of Control 31. Sub-contracting 32. Amendment SECTION E 33. Warranties and Representations 34. Indemnity 35. Limitation of liability 36. Insurances 37. Dispute Resolution 38. Severability 39. Waiver and Cumulative Remedies 40. Force Majeure 41. Disruption 2 42. Termination Rights 43. Termination on Insolvency or Change of Control 44. Exit Management 45. Compliance with the Law and Changes in the Law 46. Offences 47. Tax arrangements 48. Blacklisting 49. Conflicts of interest 50. -

Innovative Lawyers 2016

INNOVATIVE LAWYERS 2016 OCTOBER62016 FT.COM/INNOVATIVE-LAWYERS RESEARCH PARTNER SUPPORTEDBY Foreword Innovations abound with Europe in flux INNOVATIVE LAWYERS 2016 This editionofFTInnovativeLawyers, our11th, appears at a OCTOBER 62016 time of upheaval across thecontinent.Two bigconundrumsfor FT.COM/INNOVATIVE-LAWYERS thecitizens, businesses andinstitutionsofEuropewill test the foresightand ingenuityoflegal professionalsfor yearstocome: theaftermath of theUKvoteonJune23toleave theEU, and theintensifyingrefugee andmigrant crisis.Inthismagazine, we show howlawyers arealready innovating to address both (Brexit, page 8; Social Responsibility,page12). Thebusiness worldasseenthrough thelensoflawyers is changing too—new industries andalliancesare erodingthe RESEARCH PARTNER SUPPORTEDBY traditionallines of competitionand separation of sectorsfaster than ever,forcinglawyers to getahead.Lawyers areresponding by creating newtypes of firms,blurring oldboundaries in EDITOR Harriet Arnold search of newsolutions.The individual lawyer,the nature of ASSISTANT EDITOR legaladviceand theway in whichthatadviceisdelivered are Josh Spero undergoing deep change. PRODUCTION EDITOR George Kyriakos In addition,there arenew centresofpower andchangein ART DIRECTOR thelegal industry:millennialsrefusingthe partnershiptrack; Kostya Penkov DESIGNERS technologistsintroducing artificialintelligence; andgeneral Harriet Thorne, Callum Tomsett counselactingasentrepreneurs, rather than just as lawyers. PICTURE EDITORS MichaelCrabtree,AlanKnox Againstthisbackdrop, theFinancial -

Lateral Partner Moves in London January

Lateral Partner Moves in London January - February 2021 Welcome to the latest round-up of lateral partner moves in the legal market from Edwards Gibson; where we look back at announced partner-level recruitment activity in London over the past two months and give you a ‘who’s moved where’ update. There were 90 partner hires in the first two months of 2021 which, although 6% down on the 5-year statistical average for the same period, is actually 13% up on last year (80). Indeed, as we have previously discussed, Big Law has, with some exceptions, so far managed to remain remarkably unscathed by the largest economic contraction the UK has ever seen. No fewer than six firms took on three or more partners, with Hogan Lovells nabbing five: a four- partner litigation team (two laterals and two promotion hires) from Debevoise & Plimpton and the co-head of corporate - Patrick Sarch - from White & Case. Top partner recruiters in London January – February 2021 Hogan Lovells 5 Addleshaw Goddard 3 Bracewell 3 Harcus Parker 3 Paul Hastings 3 Squire Patton Boggs 3 Given the inverse relationship between economic activity and commercial disputes, it is unsurprising that nearly a third of all hires were disputes lawyers and 12% were restructuring/ insolvency specialists, with three firms - Armstrong Teasdale, McDermott Will & Emery and Simpson Thacher – launching completely new practices in that space. Firms hiring laterals whose practices were primarily restructuring or insolvency related Armstrong Teasdale (formerly Kerman & Co) Dechert Edwin Coe Faegre Drinker Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson Goodwin Procter Latham & Watkins McDermott Will & Emery (hired a two-partner team) Simpson Thacher & Bartlett (hired two partners from separate firms) Although demand for restructuring and insolvency specialists clearly remains very high, many lawyers report that work levels remain eerily quiet due to governments across Europe pumping vast amounts of cash into the system to counter a COVID- lockdown induced economic collapse. -

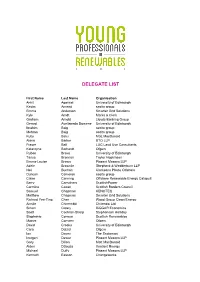

Delegate List

DELEGATE LIST First Name Last Name Organisation Ankit Agarwal University of Edinburgh Kasim Ameed seolta group Emma Anderson Smarter Grid Solutions Kyle Arndt Marks & Clerk Graham Arnold Lloyds Banking Group Gerard Avellaneda Domene University of Edinburgh Ibrahim Baig seolta group Mehran Baig seolta group Kutlu Balci Mott MacDonald Alana Barker BTO LLP Fraser Bell LUC Land Use Consultants Katarzyna Borhardt Ofgem Ruben Bravo University of Edinburgh Tanya Brennan Taylor Hopkinson Emma-Louise Brown Pinsent Masons LLP Adele Brownlie Shepherd & Wedderburn LLP Neil Buchan Clarksons Platou Offshore Duncan Cameron seolta group Claire Canning Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult Barry Carruthers ScottishPower Carmina Cazan Scottish Borders Council Samuel Chapman KENOTEQ Matthew Chapman Smarter Grid Solutions Richard Yen-Ting Chen Wood Group Clean Energy Ainslie Chinembiri Chitendai Ltd Simon Cleary BiGGAR Economics Scott Cochran-Sharp Stephenson Halliday Stephanie Conesa Scottish Renewables Maeve Convery Ofgem David Crooks University of Edinburgh Cara Dalziel Ofgem Ian Davey The Scotsman Imogen Dewar Pinsent Masons LLP Gary Dillon Mott MacDonald Alden DSouza Ventient Energy Michael Duffy Pinsent Masons LLP Kenneth Easson Changeworks Francisco M Funes Garrido AECOM Anna Garcia-Teruel The University of Edinburgh Kirsty Glennan Burness Paull LLP Philippa Godwin Pinsent Masons LLP Aileen Gordon Shepherd & Wedderburn LLP Cheral Govind Ofgem Christopher Graham The Marketing Department Steven Gregory Ofgem Barry Griffin Anderson Floor Warming & Renewables -

Law Firms Join Forces to Ensure Firms Are Equipped to Have Conversations About Race

LAW FIRMS JOIN FORCES TO ENSURE FIRMS ARE EQUIPPED TO HAVE CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACE 25 January 2021 | UK Firm news As organisations across the UK continue efforts to improve ethnic diversity and promote better understanding of race, a number of the UK’s leading law firms have joined forces to provide guidance that will enable effective conversations about race and racism in the workplace. NOTICED, the UK’s first inter-law firm diversity network which is comprised of thirteen City firms, is today launching a new toolkit offering a structured approach to conversations which many individuals otherwise feel is difficult to have. The guide, which can be viewed here addresses a range of issues. It will help individuals identify and deal with micro-aggressions, understand what actions can help them be an effective ally and hold effective conversations in the workplace. The guide also offers a number of practical solutions that law firms can take to improve. These focus on hiring and promotion and how firms can expand support beyond the legal profession. The launch of the guide follows member firms having individually taken a range of actions to address issues relating to race and ethnicity in the workplace*. Law Society of England and Wales president David Greene said: “We are pleased to contribute to NOTICED’s toolkit and hope this provides a useful resource for firms. The events of 2020 and our recent research into the experiences of black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors has shown that now more than ever it is important for firms and legal businesses to lead from the front and have frank conversations about how to create a more inclusive workforce.” Siddhartha Shukla, senior associate at Herbert Smith Freehills and co-chair of NOTICED, says: "Given the increasing focus on ethnic and cultural diversity following events of 2020, NOTICED was keen to provide something tangible for member firms and the wider legal community to use when trying to improve the quality of conversations about race in the workplace. -

English/Conventions/1 1 1969.Pdf

Women, Business and the Law Removing barriers to economic inclusion 2012 Measuring gender parity in 141 economies © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org All rights reserved. A copublication of The World Bank and the International Finance Corporation. This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This publication was made possible with the funding from the Nordic Trust Fund for Human Rights. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of the Nordic Trust Fund for Human Rights’ donors. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone 978-750-8400; fax 978-750-4470; Internet www.copyright.com All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; e-mail [email protected] Women, Business and the Law Removing barriers to economic inclusion 2012 Measuring gender parity in 141 economies Table of Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................