Bethnal Green Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 the Date of Tender for This ITT Is

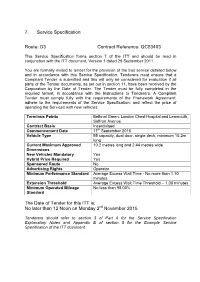

7. Service Specification Route: D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Bethnal Green, London Chest Hospital and Leamouth, Saffron Avenue Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 17th September 2016 Vehicle Type 55 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 10.2m long Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.44 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold – 1.00 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard The Date of Tender for this ITT is: nd No later than 12 Noon on Monday 2 November 2015 Tenderers should refer to section 3 of Part A for the Service Specification Explanatory Notes and Appendix B of section 5 for the Example Service Specification of the ITT document. -

Discover Old Ford Lock & Bow Wharf

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park Victoria River Lee Navigation Bonner Hall Well Street G Park Islington Hackney Bridge Common r Camden o v Green e Victoria Park R l o a a n Skew Deer Park Pavilion a d Café C Bridge n io n Re U ge n West Lake rd t’s o f C Chinese rt an He Discover al Pagoda d Se oa Grove Road Old Ford Lock w R e a c Bridge rd rd a st o l & Bow Wharf o F P ne d r R Ol to Old Ford Lock & oa ic d V Royal Bow Wharf recall Old Ford Lock Wennington London’s grimy Road industrial past. Now Bethnal Green being regenerated, Wennington it remains a great Green place to spot historic Little adventures Bow Mile End d canal features. o a Ecology on your doorstep Wharf R an Park o m STAY SAFE: R Stay Away From Mile End the Edge Mile End & Three Mills Map not to scale: covers approx 0.5 miles/0.8km Limehouse River Thames A little bit of history Old Ford Lock is where the Regent’s Canal meets the Hertford Union Canal. The lock and Bow Wharf are reminders of how these canals were once a link in the chain between the Port of London and the north. Today, regeneration means this area is a great place for family walks, bike rides and for spotting wildlife. Best of all it’s FREE!* ive things to d F o at O ld Fo rd Lo ck & Bow Wharf Information Spot old canal buildings converted to new uses and Bow Wharf canal boats moored along the canal. -

Bethnal Green Walk

WWW.TOWERHAMLETS.GOV.UK 8 THE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FOR TOWER HAMLETS PRODUCED BY YOUR COUNCIL This month Graham Barker takes a springtime stroll through the historic parks and streets of Bethnal Green and beyond. Photos by Mike Askew. Set off with a spring in your step SPRING can be an inspiring time to Continue through Ion Square Gardens, get out and about, with flowers, glimpsing Columbia Road as you reach green shoots, buds and blossom Hackney Road. breaking through. This walking You now detour briefly out of the bor- route takes in some East End high- ough. To the left of Hackney City Farm (8) lights including parks, canals, histo- enter Haggerston Park, once the Imperial ry and art. Gas Works. Tuilerie Street alongside marks We start this month’s walk at Bethnal the French tile makers who had kilns here. Green Tube station. St John’s Church (1) At the tennis courts, join the Woodland towers above you, with its elegant win- Walk as it skirts initially by the farm and dows and golden weather vane. It was then left uphill and around the BMX track. designed in 1825 by Bank of England archi- On reaching Goldsmith’s Row, turn left – tect Sir John Soane and holds a command- beware of enthusiastic cyclists – cross to ing position. the Albion pub and continue on over the Cross at the lights in front of the church, Regent’s Canal hump-backed bridge. and there, behind Paradise Gardens, sits Ahead is Broadway Market (9), full of inter- Paradise Row, cobbled and narrow. -

J?, ///? Minor Professor

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 APPROVED! Major professor ^ J?, ///? Minor Professor ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History Dean"of the Graduate School THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For she Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Denis George Paz, B. A, Denton, Texas January, 1969 PREFACE Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri- torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over dioceses styled after English place names rather than over districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati- k can s opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area and was ready to take its place as a full member of the Roman Catholic communion. When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid- dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen his position, issued a public letter in which he charac- terized the letters apostolic as an "insolent and insidious"1 attack on the queen's prerogative to appoint bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op- position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title, ill and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to have violated the act. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

The Manufacture of Matches

Life and Work: Poverty, Wealth and History in the East End of London Part One: The East End in Time and Space Time: The Historical Life of the East End Resource Spitalfields By Sydney Maddocks From: The Copartnership Herald, December 1931-January 1932 With the exception of its inhabitants and of those who have business there to attract them, Spitalfields is but little known even to a large number of the population of East London, whose acquaintance with it is often confined only to an occasional journey in a tramcar along Commercial Street, the corridor leading from Whitechapel to Shoreditch. By them the choice of the site of the church, as well as that of the market, may very easily be attributed to the importance of the thoroughfare in which they are both now found; but such is not the case, for until the middle of the last century Commercial Street had not been cut through the district. The principal approach to Spitalfields had previously been from Norton Folgate by Union Street, which, after a widening, was referred to in 1808 as "a very excellent modern improvement." About fifty years ago this street was renamed Brushfield Street, after Mr. Richard Brushfield, a gentleman prominent in the conduct of local affairs. The neighbourhood has undergone many changes during the last few years owing to rebuilding and to the extension of the market, but the modern aspect of the locality is not, on this occasion, under review, for the references which here follow concern its past, and relate to the manner of its early constitution. -

East London History Society Speakers for Our Lecture Programme Are Always Welcomed

T 6sta 0 NEWSLETTER oniort Volume 3 Issue 05 January 2010 0 c I 11A4 Uggeo {WI .41 ea. 1414...... r..4 I.M. minnghtep 111. `.wry caag, hew. Nor., +.11 lc, 2/10 .11,..4e...1..1 lo: tn... F..... mad. I.4.. xis Mock 14.1Ing 1934: The largest salmon ever sold in Billingsgate Fish Market, weighing in at 74Ibs. This beauty came from Norway and sold for 2/10 a pound when typical prices were 2/3. Louis Forman stands behind the salmon wearing a black Hombcrg hat. CONTENTS: Editorial Note Memorial Research 2 Book Etc 8 Programme Details Olympic Site Update 3 Bethnal Green Tube Disaster 9 Tower Hamlets Archives 4 East End Photographers 7 — James Pitt 12 St Georges Lutheran Church Talks 5 Missionaries in Bow 14 Correspondence 6 Strange Death from Chloroform 15 Notes and News 7 Spring Coach Trip 2010 16 ELHS Newsletter January 2010 Editorial Note: MEMORIAL RESEARCH I The Committee members are as follows: Philip Mernick, Chairman, Doreen Kendall, On the second Sunday of every month Secretary, Harold Mernick, Membership, members of our Society can be found David Behr, Programme, Ann Sansom, recording memorials in Tower Hamlets Doreen Osborne, Howard Isenberg and Cemetery known locally as Bow Cemetery. Rosemary Taylor. Every memorial gives clues to the family interred such as relationships and careers. All queries regarding membership should be addressed to Harold Mernick, 42 Campbell With modern technology it is possible to call Road, Bow, London E3 4DT. up at the L.M.A. all leading newspapers till 1900. It gives us a great feeling when we Enquiries to Doreen Kendall, 20 Puteaux discover another clue to the hidden history of House, Cranbrook Estate, Bethnal Green, the cemetery. -

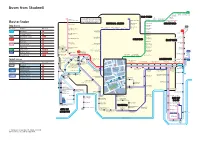

Buses from Shadwell from Buses

Buses from Shadwell 339 Cathall Leytonstone High Road Road Grove Green Road Leytonstone OLD FORD Stratford The yellow tinted area includes every East Village 135 Old Street D3 Hackney Queen Elizabeth Moorfields Eye Hospital bus stop up to about one-and-a-half London Chest Hospital Fish Island Wick Olympic Park Stratford City Bus Station miles from Shadwell. Main stops are for Stratford shown in the white area outside. Route finder Old Ford Road Tredegar Road Old Street BETHNAL GREEN Peel Grove STRATFORD Day buses Roman Road Old Ford Road Ford Road N15 Bethnal Green Road Bethnal Green Road York Hall continues to Bus route Towards Bus stops Great Eastern Street Pollard Row Wilmot Street Bethnal Green Roman Road Romford Ravey Street Grove Road Vallance Road 115 15 Blackwall _ Weavers Fields Grove Road East Ham St Barnabas Church White Horse Great Eastern Street Trafalgar Square ^ Curtain Road Grove Road Arbery Road 100 Elephant & Castle [ c Vallance Road East Ham Fakruddin Street Grove Road Newham Town Hall Shoreditch High Street Lichfield Road 115 Aldgate ^ MILE END EAST HAM East Ham _ Mile End Bishopsgate Upton Park Primrose Street Vallance Road Mile End Road Boleyn 135 Crossharbour _ Old Montague Street Regents Canal Liverpool Street Harford Street Old Street ^ Wormwood Street Liverpool Street Bishopsgate Ernest Street Plaistow Greengate 339 Leytonstone ] ` a Royal London Hospital Harford Street Bishopsgate for Whitechapel Dongola Road N551 Camomile Street 115 Aldgate East Bethnal Green Z [ d Dukes Place continues to D3 Whitechapel Canning -

The Jubilee Greenway. Section 3 of 10

Transport for London. The Jubilee Greenway. Section 3 of 10. Camden Lock to Victoria Park. Section start: Camden Lock. Nearest stations Camden Town , Camden Road . to start: Section finish: Victoria Park - Canal Gate. Nearest stations Cambridge Heath or Bethnal Green . to finish: Section distance: 4.7 miles (7.6 kilometres). Introduction. Section three is a satisfying stretch along the Regent's Canal, from famous Camden Lock to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. This section highlights the contrasts of a living, growing capital, meandering between old districts and new developments, each with their own unique style and atmosphere. This section of the route takes the walker through Camden Town, Islington, Hackney and Bethnal Green, leading finally to Victoria Park. This provides a fascinating look at how London is changing; passing many new developments and constructions, while savouring the atmosphere of the canal. In some ways the towpath side has changed little, whereas the south side of the canal has developed a great deal. For walkers interested in the history of London's canals you will pass near the London Canal Museum on this section. Look out for the Jubilee Greenway discs in the pavement as you go round. Continues below Directions. To start section three from section two, continue along the towpath past Camden Lock Market. Cyclists have to dismount through the market area here. Coming from Camden Town station, turn left, cross over the road and the bridge to find the towpath on the north side of the canal. Once on the canal towpath, pass rows of Vespa Scooters used as cafe seats and a large bronze lion, as well as many food stalls. -

Poverty, Wealth and History in the East End of London : Life and Work

Poverty, Wealth and History in the East End of London : Life and Work Part 3 : Labour and Toil Assessment 2 : The Standard of Living Author : Paul Johnson How can we assess the standard of living in the East End and what kind of comparisons can we make? Using a variety of sources creatively and knowing what sources you need to solve a problem are among the essential skills of a historian. We have provided you with: 1. A table listing the average wage and expenditures in the 1880s and 2000 2. An article tha t appeared in The Builder periodical in 1871 about the dwellings of the poor in Bethnal Green 3. Images from the Illustrated London News detailing life in the East End of London Find out how well equipped you are to assess the standard of living in the East End of London by answering the questions below and comparing your answers to Paul's thoughts. “Homes in the East of London”, The Builder, 28th January 1871 The average income and expenditure in the 1880s and 2000. P. Wilser, The Pound in Your Pocket, 1870-1970, Peter Wilser 1970; J. McGinty and T. Williams (Eds.) National Statistics. Regional Trends, 2001 ed., London: The Stationery Office We traversed several alleys and courts, dirty and dismal, the denizens of which told their own tales in their pallid faces and tattered raiment. Here and about, the pavement of the streets, the flagging of the paths, the condition of the side channels, and the general state of the entries and back-yards are unendurably bad. -

Bethnal Green Ward Profile

Bethnal Green Ward Profile Corporate Research Unit May 2014 Page 1 Contents Population ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Ethnicity .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Religion ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Housing ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Health - Limiting illness or disability ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Unpaid care provision ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Labour market participation ........................................................................................................................................................................................................