Russell Dumas.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PO, Canberra, AX.T. 2601, Australia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 056 303 AC 012 071 TITLE Handbook o Australian h'ult Educatial. INSTITUTION Australian Association of AdultEducati. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 147p. 3rd edition AVAILABLE FROMAustralian Association ofAdult Education, Box 1346, P.O., Canberra, AX.T. 2601,Australia (no price quoted) EDRS PRICE Mr-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DEsCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Day Programs;*Directories; *Educational Facilities; EveningPrograms; *Professional Associations;*University Extension IDENTIFIERS Asia; Australia; New Zealand;South Pacific ABSTRACT The aim of this handbookis to provide a quick reference source for a number ofdifferent publics. It should be of regular assistance to adult andother educators, personnelofficers and social workers, whoseadvice and help is constantlybeing sought about the availability ofadult education facilities intheir own, or in other states. The aim incompiling the Handbook has been tobring together at the National and Statelevels all the major agencies--university, statutory body,government departments and voluntary bodies--that provide programsof teaching for adults open to members of thepublic. There are listed also thelarge number of goverrmental or voluntary bodi_eswhich undertake educationalwork in special areas. The Handbook alsolists all the major public institutions--State Libraries, Museums,and Art Galleriesthat serve importantly to supplement thedirect teaching of adults bytheir collections. New entries includebrief accounts of adult educationin the Northern Territory andin the Territory of Papua-NewGuinea, and the -

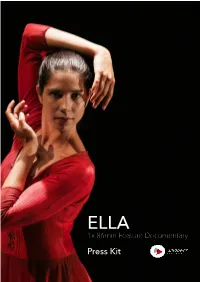

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

Remembering Edouard Borovansky and His Company 1939–1959

REMEMBERING EDOUARD BOROVANSKY AND HIS COMPANY 1939–1959 Marie Ada Couper Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne 1 ABSTRACT This project sets out to establish that Edouard Borovansky, an ex-Ballets Russes danseur/ teacher/choreographer/producer, was ‘the father of Australian ballet’. With the backing of J. C. Williamson’s Theatres Limited, he created and maintained a professional ballet company which performed in commercial theatre for almost twenty years. This was a business arrangement, and he received no revenue from either government or private sources. The longevity of the Borovansky Australian Ballet company, under the direction of one person, was a remarkable achievement that has never been officially recognised. The principal intention of this undertaking is to define Borovansky’s proper place in the theatrical history of Australia. Although technically not the first Australian professional ballet company, the Borovansky Australian Ballet outlasted all its rivals until its transformation into the Australian Ballet in the early 1960s, with Borovansky remaining the sole person in charge until his death in 1959. In Australian theatre the 1930s was dominated by variety shows and musical comedies, which had replaced the pantomimes of the 19th century although the annual Christmas pantomime remained on the calendar for many years. Cinemas (referred to as ‘picture theatres’) had all but replaced live theatre as mass entertainment. The extremely rare event of a ballet performance was considered an exotic art reserved for the upper classes. ‘Culture’ was a word dismissed by many Australians as undefinable and generally unattainable because of our colonial heritage, which had long been the focus of English attitudes. -

DVD/Video Auditions

Application Form 2017 - DVD/Video Auditions Australian & New Zealand Residents only International DVD/USB/YouTube or Vimeo Link Application available from www.australianballetschool.com.au Applicant details Audition Surname DVD Application USB Application YouTube link - unlisted Vimeo link - unlisted First Name Link: (insert URL) Date of birth Age at 30 June 2017 The Australian Ballet School Training Programme Gender Female Male (Please tick appropriate box – Applicable to intake year, January 2018) Australian Citizen Yes No, please state Interstate/International Training Programme Academic Education (School year presently undertaking) Approximate age 9-14 years (Levels 1-4) Postal Address After School Programme (Melbourne) Approximate age 9-13 years (Levels 1-3) Full-Time Programme (Melbourne) Suburb Approximate age 13-18 years (Levels 4-8) State Postcode If successful, I would be interested in Boarding at Marilyn Rowe House Country Declaration Applicants 18+ or parent/guardian of applicants under 18 years of age Phone (1) Phone (2) I authorise staff of The Australian Ballet School, in the case of an emergency, to obtain all necessary medical assistance and Email treatment. I agree to meet any expenses attached to such treatment I would like to receive information of news and events (including eNewsletter) Signature: Must sign Date: Parent/Guardian details If applicant under 18 years of age / / Parent/Guardian Name Payment details Phone (1) Phone (2) Mastercard Visa Email Cheque/Money Order made payable to The Australian Ballet School (Please write applicant name on reverse of cheque) I would like to receive information of news and events (including eNewsletter) AU$160 (DVD/Video Application Fee) Total Amount AU$ Dance School details Card Number Dance School Card Expiry / CVV Dance Teacher(s) Card Name Signature Postal Address In submitting this application to The Australian Ballet School applicants/parents/guardians agree with the Conditions of Enrolment Suburb and general Audition Information which accompanies this application. -

SOUTHBANK LOCAL NEWS ISSUE 01 Welcome to the Southbank Local News

OCTOBER 2011 ISSUE 01 PRICELESS WWW.SOUTHBANKLOCALNEWS.COM.AU : SOUTHBANK_News The voice of Southbank Choir Founder joins Rotary Waterfront guide launched See page 2 See page 5 Cadel Conquers Southbank Hats off to our restaurants See page 3 See page 7 Southbank ‘zoned out’ of primary school By Sean Rogasch stressed the school wanted the department to Southbank children are in look at restructuring other schools zones, so no danger of being without a children were without a local primary school. “We’d like to see a rationalisation of the other local primary school if a new schools zones,” Mr Martin said. neighbourhood boundary If the new zone was implemented without proposed by Port Melbourne any changes to others it would leave most of Primary School is accepted. Southbank and much of South Melbourne without access to a local primary school. Port Melbourne is one of two “unzoned” It will also mean St Kilda Primary was the government schools that children in the nearest government school to the vast Southbank region can currently attend. majority of Southbank families who live outside of the proposed new boundary. At a Southbank Residents Group (SRG) meeting in August, Albert Park MP Martin But St Kilda could hardly be considered Foley said a large number of primary school local, as parents would have to pass six other kids would be aff ected. primary schools to get there. Mr Foley presented residents with a map Mr Foley stressed his support for a new showing the proposed zone. It included primary school, adding: “If we want a northern zone line along the Yarra River, community, rather than just a collection of which will come into aff ect next year. -

2019 Annual Report Celebrating 55 Years of the Australian Ballet School

2019 Annual Report Celebrating 55 Years of The Australian Ballet School 1 The Australian Ballet School 2019 Annual Report “The highly entertaining program for Summer Season 2019 again highlights The Australian Ballet School as not just an esteemed and invaluable institute but as a trusted brand for brightly polished, modestly priced performances.” Simon Parris: Man in Chair (Theatre, Opera and Ballet Reviewer), December 2019 2 The Australian Ballet School 2019 Annual Report 3 The Australian Ballet School 2019 Annual Report Vale Dame Margaret Scott In the 55th year of The Australian Ballet School, Founding Director Dame Margaret Scott AC DBE passed away peacefully on 24 February. Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, Dame Margaret began her professional dance career with Sadler’s Wells Ballet in London, where she was appointed Principal in 1941. She soon joined Ballet Rambert, also in London, and was Principal from 1943 to 1948. She arrived in Australia in 1947 as part of Ballet Rambert’s overseas tour and chose to remain. Dame Margaret was a founding member of the National Theatre Ballet in Melbourne and danced in its early seasons as Principal. In the late 1950s, she was involved in negotiations with the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, which led to the formation of The Australian Ballet. In 1964, she was appointed Founding Director of The Australian Ballet School, and continued in that role until 1990. She was invested as a Dame Commander of the British Empire (DBE) in 1981 for services to ballet. This followed the earlier award of an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1976. -

THE ARTS Name Genre Years School Alsop, John Radio & TV Script Writer / Director 1966-71 Whitefriars

THE ARTS Name Genre Years School Alsop, John Radio & TV script writer / Director 1966-71 Whitefriars Achievements / Major Awards & Nominations “Brides of Christ” won scriptwriting awards from the AFI, Australian Writers’ Guild; as well as receiving an International Emmy Award nomination. “The Leaving of Liverpool” also received an AFI award for Best TV Screenplay and a Writers’ Guild Awgie for Best Screenplay (mini Series). The production also won AFI awards and an ATOM award. “Bordertown” Episodes 7 & 8 (“The Cracks and The Squares”) “R.A.N. Remote Area Nurse” Episode Two won its year’s Best Screenplay (Television Series) Australian Writers’ Guild Awgie Award. Also Recipient of the Hector Crawford Award for Contribution to Script Editing in a body of work. In 2007 received an Asialink grant to develop a script with an Australian-Filipino connection, resulting in the short film “He She It”, which premiered as part of the Accelerator program at the Melbourne Film Festival and also screened at more than a dozen international film festivals. The 2008 Foxtel Fellowship for achievement in television writing funded development of a feature film script currently at the production finance stage. Borrack, John Visual Arts 1950 Parade A master colourist predominantly in watercolour and gouache, John Borrack has described his art as “a celebration of the natural world and its wonders that are all around us”. He has been described as “something of a maverick, a man who has dedicated the last 50 years of his life to the pursuit of a pure, spiritual expression”. John and his wife, Gillian, have campaigned against the Plenty Valley growth corridor. -

Melbourne Arts Precinct Blueprint 4 March 2014

Report to the Future Melbourne (Planning) Committee Agenda item 6.2 Melbourne Arts Precinct Blueprint 4 March 2014 Presenter: Rob Adams, Director City Design Purpose and background 1. The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the recent public release of the Melbourne Arts Precinct Blueprint (Blueprint) and advise on the implications for Council. 2. The preparation of a Blueprint to guide the future development of the Melbourne’s Arts Precinct was initiated in May 2011 by the Victorian Government and presents a shared vision for the future of the area as determined by a working group, chaired by architect Yvonne von Hartel AM and comprising key precinct stakeholders including Arts Victoria, City of Melbourne, University of Melbourne and major arts institutions. Key issues 3. The principles underpinning the Blueprint were informed by a community consultation process that involved representatives of arts organisations, residents, arts students and visitors to the precinct. 4. The Blueprint identifies that the precinct has the potential to be a vibrant and active destination and proposes that this will only be fully realised when all levels of government agree to cooperate in the facilitation of this special place. Council’s ongoing participation in the implementation of projects in the public realm is one way by which this overall vision can be achieved (refer Attachment 2). 5. The Blueprint is consistent with Council’s adopted Southbank Structure Plan and includes actions such as the streetscape improvements to City Road, open space along Southbank Boulevard and the integration of Dodds Street with the VCA campus. -

Wednesday 5 May 2021 Media Release a High Note to 2020: The

Wednesday 5 May 2021 Media Release A high note to 2020: The performing arts industry celebrates four leading lights in long-awaited Industry Achievement Awards announcement The Industry Achievement Award recipients for 2020 have been revealed and honoured: 2020 JC Williamson Award® Deborah Cheetham AO and David McAllister AM Sue Nattrass Award® Jill Smith AM and Ann Tonks AM Melbourne, Australia: Live Performance Australia (LPA) today announced and honoured four of Australia’s most celebrated live performance luminaries in a postponed 2020 Industry Achievement Awards ceremony, which took place on Wednesday 5 May at Melbourne Recital Centre. Deborah Cheetham AO and David McAllister AM have been announced as the recipients of the 2020 JC Williamson Award®, the foremost honour that the Australian live entertainment industry can bestow. In awarding the 2020 JC Williamson Award®, LPA recognises an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the Australian live entertainment and performing arts industry and shaped the future of our industry for the better. At the same event Jill Smith AM and Ann Tonks AM were revealed as the dual recipients of the 2020 Sue Nattrass Award®. This prestigious award honours exceptional service to the Australian live performance industry, shining a spotlight on people in service roles that support and drive our industry, roles that have proved particularly crucial in ensuring the sector’s survival over the past year. 2020 JC Williamson Award® Yorta Yorta woman, soprano, composer and educator Professor Deborah Cheetham AO, has been a leader and pioneer in the Australian arts landscape for more than 25 years. In 2009, Deborah established Short Black Opera with her partner Toni Lalich OAM, as a national not-for-profit opera company devoted to the development of Indigenous singers. -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

Australian Official Journal Of

Vol: 19 , No. 49 15 December 2005 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 15 December 2005 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 15666 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 15668 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 15666 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registartion/Protection .......... 15416 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1086850 to 1088113 ............................. 15399 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 15669 Withdrawn..................................... 15669 Assignments, Trasnmittals and Transfers .................. 15669 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 15670 Corrigenda ...................................... 15671 Notices ........................................ 15666 Opposition Proceedings ............................. 15665 Removal/Cessation