Music, Memory, and Waiting: Living Life in a Series of Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record-Mirror-1964-1

RecordA MERRY CHRISTMAS MirrorTO ALL OUR READERS Largest selling colour pop veekly newspaper No. 197 Week ending December 19, 1964 Every Thursday 6d.Registered at the G.P.O. as a newspaper THE ROLLING STONES - almost every pop honour has been heaped established themselves as deeply as possible into the pop world. Now, they upon the shoulders of the fivesome during the past year, and the boys have are on holiday over Christmas, all going their separate ways. matt PARLOPHONE meritE.M.I. RECORDS LTD., E M I. HOUSE, 20 MANCHESTER SQUARE, LONDON W I 2 RECORD MIRROR, Week ending December 19, 1964 ... t tl e dt s tl m ?tn s ct Ri aboutthe ? LETTERS Y UR PAGETI,111M=,IMMINEWIT.- Record `IT'S BEEN A BAD Mirror EVERY THURSDAY 116 Shaftesbury Avenue, London W.I. YEAR FOR -AMERICA' Telephones GERrard 7942/3/4 says an AM reader AS '64 draws to a close, it mustoneofthe worstyearsforAmerican EDITORIAL originals,Surelythedisc - buying public must be fed up with the old rope dished out by the majority of Bri- Let's have a tishartistes.Inthecharts now: terrible covered or re- vivedversions ofg r e a t songs by Sam Cooke, Major MERRY Christmas ! Lance, Shirelles G -Clefs, JackiedeShan'non,Four FORGET,foramoment,thedisputes,the Tops.AndpooroldLou squabbles,theconstantpanicabout chart Johnson. After the first or- THE G-CLEFS-Their original "I Understand" hit our JACKIE DE SHANNON- deal by Sandie Shaw, Adam positions and polls and percentages-let's just wish top twenty on New Year's day, 1962. No hits yet here. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 No. 134 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was Act of 1965 to provide for the refinancing of ensuring that the words of Senators called to order by the President pro certain Federal student loans, and for other past and present are correctly recorded tempore (Mr. LEAHY). purposes. for the American people. While he has SCHEDULE been here, he has witnessed many PRAYER Mr. REID. Mr. President, following events. He has seen five different Presi- The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- my remarks, the Senate will be in re- dents occupy the White House, worked fered the following prayer: cess subject to the call of the Chair for with eight different majority leaders, Let us pray. the joint meeting with the President of transcribed speeches on everything Eternal God, who restores peace in Ukraine. from the Berlin Wall to Senator Byrd’s human hearts, thank You for Your When the Senate reconvenes, it will legendary lectures on the history of many blessings. Guide our lawmakers be in a period of morning business until the Senate. so that they will discern Your purposes 1 p.m., with the time equally divided I wish Jerry all the best in his well- and become instruments of Your provi- and controlled between the two leaders deserved retirement. I have no doubt dence. Today, help them to speak or their designees. -

The Heat Wave Issue

MAGAZINE ZURICH AUSGABE 32 SUMMER 2021 CHF 8.50 PERSONALITIES DAMIEN HIRST – GRAYDON CARTER PORTFOLIO BLACK ART MATTERS FASHION HAUTE COUTURE ESCAPE BORDEAUX – TOSKANA UHREN DIVER WITH ENGLISH TEXT 32 710450 772297 9 Extremely Addictive THE HEAT WAVE ISSUE 106 JUILLET - AOÛT 2021 107 JUILLET - AOÛT 2021 Editorial ... and the livin’ is easy ... and the livin’ is easy Ich hoffe, die meteorologischen Tiefs haben sich I hope the meteorological lows have passed by the verzogen, bis Sie die Sommerausgabe von time you have the summer issue of COTE MAGAZINE COTE MAGAZINE in den Händen haben. Wir möchten in your hands. We would like to keep our cover promise. unser Cover-Versprechen nämlich gern einhalten. Of course, we can‘t influence weather patterns, but Natürlich können wir das Wettergeschehen nicht what we can confirm is this: we have done everything in beeinflussen, was wir aber bestätigen, ist: Wir haben our power to ensure that you have an intriguing and opulent alles daran gesetzt, dass Sie eine spannende und magazine in your hands that will make your summer, opulente Zeitschrift in den Händen halten, die Ihnen wherever you will spend it, a little more exciting. Even if den Sommer, wo immer Sie ihn verbringen werden, the grey storm clouds should prove stubborn. etwas aufregender macht. Auch wenn die grauen Gewitterwolken sich als hartnäckig erweisen sollten. Rather than play weather fairy, we‘d like to brighten your mood - not that you need it, but the past few months Lieber als Wetterfee spielen wollen wir Ihr Gemüt have gnawed at all of us, somehow. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Janie Bradford

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Janie Bradford Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Bradford, Janie, 1939- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Janie Bradford, Dates: November 19, 2019 and November 28, 2012 Bulk Dates: 2012 and 2019 Physical 10 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:26:04). Description: Abstract: Songwriter Janie Bradford (1939 - ) was a songwriter at Motown Records for twenty-eight years, writing songs such as “Money (That's What I Want),” “Tie a String Around Your Finger,” and “Too Busy Thinking About My Baby.” Bradford was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on November 19, 2019 and November 28, 2012, in Los Angeles, California. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2012_252 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Songwriter Janie Bradford was born on June 2, 1939 in Charleston, Missouri to Richard Henry and Elizabeth Bradford. Bradford attended Birds Mill Elementary School and Lincoln High School. Upon graduation, Bradford attended the Detroit Institute of Technology in 1956. In Detroit, Bradford lived with her sister, Clea Ethel. Their neighbor was Jackie Wilson, who introduced Bradford to the founder of Motown Records, Berry Gordy. In 1958, Bradford joined Motown Records as a secretary, but soon became a songwriter for Motown singers. The first two songs she co-authored with Gordy were included on Jackie Wilson’s album, Lonely Teardrops. The next collaboration that Bradford co-wrote with Gordy was the song “Money (That’s What I Want),” which has been covered over two hundred times by artists such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Muddy Watters, The Supremes, The Flying Lizards and Boyz II Men. -

Protest, Justice, and Transnational Organizing SAN FRANCISCO, CA 2020 NWSA Chair and Director Meeting

NWSA’S 40TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Protest, Justice, and Transnational Organizing 2019 NWSA ANNUAL CONFERENCE: Protest, Justice, and Transnational Organizing NOV 14–17, 2019 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA NOVEMBER 2018 14-17, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 2020 NWSA Chair and Director Meeting About Friday March 6th The 2020 Chair and Director meeting will be focused on the different responses Chicago, IL to external pressures experienced by departments, programs, and centers. This event is intended to promote field- building by bringing together program and department chairs and women’s center directors for a day-long meeting as an added benefit of institutional membership. Participants will exchange ideas and strategies focused on program and center administration, curriculum development, and pedagogy, among other topics. Participation requirements: • 2020 institutional membership • Chair and Director Meeting registration fee $125 • Registration form DEADLINE The fee includes participation in the event and TO REGISTER: breakfast and lunch the day of the meeting. It does not include travel. NWSA will cover one night’s FEBRUARY 15, 2020 accommodations for those who require it. 2019 NWSA ANNUAL CONFERENCE: Protest, Justice, and Transnational Organizing NOV 14–17, 2019 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA Table of Contents President’s Welcome ........................................... 4 A Brief (and Incomplete) History of the NWSA Women of Color Caucus ................................... 43 Conference Maps ............................................... 5 NWSA Receptions -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861

RCA Discography Part 15 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LSP 4600-4861 LSP 4600 LSP 4601 – Award Winners – Hank Snow [1971] Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down/I Threw Away The Rose/Ribbon Of Darkness/No One Will Ever Know/Just Bidin' My Time/Snowbird/The Sea Shores Of Old Mexico/Me And Bobby Mcgee/For The Good Times/Gypsy Feet LSP 4602 – Rockin’ – Guess Who [1972] Heartbroken Bopper/Get You Ribbons On/Smoke Big Factory/Arrivederci Girl/Guns, Guns, Guns/Running Bear/Back To The City/Your Nashville Sneakers/Herbert's A Loser/Hi, Rockers: Sea Of Love, Heaven Only Moved Once Yesterday, Don't You Want Me? LSP 4603 – Coat of Many Colors – Dolly Parton [1971] Coat Of Many Colors/Traveling Man/My Blue Tears/If I Lose My Mind/The Mystery Of The Mystery/She Never Met A Man (She Didn't Like)/Early Morning Breeze/The Way I See You/Here I Am/A Better Place To Live LSP 4604 – First 15 Years – Hank Locklin [1971]Please Help Me/Send Me the Pillow You Dream On/I Don’t Apologize/Release Me/Country Hall of Fame/Before the Next Teardrop Falls/Danny Boy/Flying South/Anna (With Nashville Brass)/Happy Journey LSP 4605 – Charlotte Fever – Kenny Price [1971] Charlotte Fever/You Can't Take It With You/Me And You And A Dog Named Boo/Ruby (Are You Mad At Your Man)/She Cried/Workin' Man Blues/Jody And The Kid/Destination Anywhere/For The Good Times/Super Sideman LSP 4606 – Have You Heard Dottie West – Dottie West [1971] You're The Other Half Of Me/Just One Time/Once You Were Mine/Put Your Hand -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL XIV SPRING 1978 No. 49 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/jemfquarterlyser1978john . — LETTERS Sir: Here's some microtrivia that may be of use to have had previous experience in the phonograph someone: the people sitting in the second row in record business and possibly had an interest in the picture of the WNAX "Dinner Bell Roundup" cast a NYRL in NYC. At any rate there is the re- on p. 110 of JEMFQ #43 spent some time in Maine. peated second-hand story that Satherley record- Jimmy and Dick (The Novelty Boys) and their troupe ed some NYRL material in a similarly named stu- summered in the Bangor area 1939-42 and again in dio in NYC. the late '40s (I believe). Jimmie Pierson and Dick The first record was pressed in Grafton Klasi were the core of the group. Jimmie 's bro- (their only pressing plant, a few miles from ther "Flash Willie" in Bernard Haeerty's (mentioned their furniture factory in Port Washington) on article on Radio Station WNAX \_JEMFQ #40, p. 18l]) 29 June 1917. played fiddle. Cora Dean ("the Kansas City Kitty") was the Pierson brothers' sister and married to In a building across from the pressing Dick. Jimmie was married (or otherwise attached) plant a recording facility (electrical) was to a lady named Dot. They were enormously popular started in about the end of 1927. Marsh Studios everyone remembers them. My memory is hazy, but in Chicago, a New York recording studio, Gennett one of the women died, her husband had some kind Studios in Richmond and other recording facili- of breakdown and the group broke up. -

James Brown’S Keyboard Composition by Taking Multiple Photographs His Well-Lighted Path?

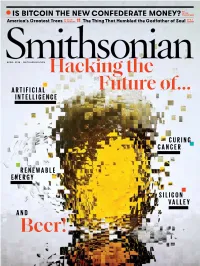

BY CLIVE IS BITCOIN THE NEW CONFEDERATE MONEY? THOMPSON BY ZACH BY RJ America’s Greatest Trees ST. GEORGE The Thing That Humbled the Godfather of Soul SMITH APRIL 2018 • SMITHSONIAN.COM Hacking the ARTIFICIAL Future of... INTELLIGENCE CURING CANCER RENEWABLE ENERGY SILICON VALLEY AND Beer! ADVERTISEMENT Join us for the 2nd annual at March 30 – April 1, 2018 Walter E. Washington Convention Center • Washington, DC Where Science Meets Science Fiction special guests include: Stan Lee, CREATOR, SPIDER-MAN Stephen Amell, Arrow • Dave Bautista, Guardians of the Galaxy • John Boyega, STAR WARS: The Last Jedi Rich DeVaul, Director of Mad Science at X, the moonshot factory • Chris Carberry, CEO, Explore Mars, Inc. Jared Espley, NASA • Terry Hurford, NASA • Erin Macdonald, Dr. Erin Explains the Universe Michael Rooker, Guardians of the Galaxy • Michael Rosenbaum, Smallville • Joan Salute, NASA Tom Welling, Smallville • Cress Williams, Black Lightning • special guest from LOST IN SPACE For more information and to purchase tickets Smithsonian.com/futurecon # futurecon sponsored by Vol. 49 | No. 01 April 2018 features 32 44 Where the Saving Miss Future Is Born Vanessa Fifty years ago, Stanley A new therapy that Kubrick foresaw the uses the body’s own world we live in today immune system to in his pioneering sci-fi fi ght cancer is off ering thriller 2001: A Space hope to patients with Odyssey. Now a new advanced disease generation of innova- by Robin Marantz Henig tors is forging the next revolutions by T. A. Frail 56 Tomorrow Land Silicon Valley’s 34 -

Pendragon Treasures People

THE GREAT BOOK OF PENDRAGON TREASURES PEOPLE Two New Round Table Knights Following are two former player characters from an old Pendragon campaign that I ran last year. They were both rather interesting fellows who became Knights of the Round Table very shortly after it was founded. They might make interesting NPCs for other people's Pendragon campaigns. AMLYN TRIADADD, KNIGHT OF THE ROUND TABLE, "THE NEKKID KNIGHT" [517] Name: Amlyn Triadadd Siz: 15 Damage: 5d6 Homeland: Huntington Dex: 13 Healing Rate: 3 Culture: Cymric/Christian Str: 18 Movement Rate: 3 Lord: Earl of Logres Con: 15 Hit Points: 28 Glory: 7382 App: 12 Unconscious: 7 Shield: A gold cross upon a blue background. PERSONALITY TRAITS SKILLS COMBAT SKILLS Chaste 11 / Lustful 9 Awareness 10 Battle 6 Energetic 13 / Lazy 7 Boating 2 Horsemanship 15 Forgiving 16 / Vengeful 4 Chirurgery 1 Sword 17 Generous 12 / Selfish 8 Compose 3 Lance 15 Honest 9 / Deceitful 11 Courtesy 9 Dagger 4 Just 12 / Arbitrary 8 Dancing 2 Spear 5 Merciful 9 / Cruel 11 Faerie Lore 3 Modest 9 / Proud 11 First Aid 10 HORSES Pious 11 / Wordly 9 Flirting 5 Prudent 9 / Reckless 11 Folk Lore 2 Charger Temperate 10 / Indulgent 10 Gaming 9 6d6 Damage Trusting 12 / Suspicious 8 Hawking 3 Valorous 17 / Cowardly 3 Heraldry 2 Hunting 6 Directed: Suspicious Saxons +2 Intrigue 7 Orate 3 PASSIONS Play Harp 18 Amor (Guenever) 12 Read Latin 3 Hate (Saxons) 7 Recognize 5 Honor 10 Religion 6 Hospitality 10 Singing 3 Love (family) 11 Stewardship 2 Loyalty (Earl Robert) 18 Swimming 3 Loyalty (Friends) 10 Tourney 1 Loyalty (King Arthur) 7 EQUIPMENT Reinforced Norman Chain + Helm (12 pts) Sword BACKGROUND & PERSONALITY Amlyn first gained a name for himself when he defended a crone against a knight she had once ensorcelled. -

The World of SOUL PRICE: $1 25

BillboardTheSOUL WorldPRICE: of $1 25 Documenting the impact of Blues and R&Bupon ourmusical culture The Great Sound of Soul isonATLANTIC *Aretha Franklin *WilsonPickett Sledge *1°e16::::rifters* Percy *Young Rascals Estherc Phillipsi * Barbara.44Lewis Wi gal Sow B * rBotr ho*ethrserSE:t BUM S010111011 Henry(Dial) Clarence"Frogman" Sweet Inspirations * Benny Latimore (Dade) Ste tti L lBriglit *Pa JuniorWells he Bhiebelles aBel F M 1841 Broadway,ATLANTIC The Great Sound of Soul isonATCO Conley Arthur *KingCurtis * Jimmy Hughes (Fame) *BellE Mg DeOniaCkS" MaryWells capitols The pat FreemanlFamel DonVarner (SouthCamp) *Darrell Banks *Dee DeeSharp (SouthCamp) * AlJohnson * Percy Wiggins *-Clarence Carter(Fame) ATCONew York, N.Y. 10023 THE BLUES: A Document in Depth THIS,the first annual issue of The World of Soul, is the initial step by Billboard to document in depth the blues and its many derivatives. Blues, as a musical form, has had and continues to have a profound effect on the entire music industry, both in the United States and abroad. Blues constitute a rich cultural entity in its pure form; but its influence goes far beyond this-for itis the bedrock of jazz, the basis of much of folk and country music and it is closely akin to gospel. But finally and most importantly, blues and its derivatives- and the concept of soul-are major factors in today's pop music. In fact, it is no exaggeration to state flatly that blues, a truly American idiom, is the most pervasive element in American music COVER PHOTO today. Ray Charles symbolizes the World Therefore we have embarked on this study of blues. -

Marina and the Diamonds Album Free Download Zip Marina and the Diamonds Album Free Download Zip

marina and the diamonds album free download zip Marina and the diamonds album free download zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66c5f4ee7e640056 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Marina and the diamonds album free download zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. -

2017-04-10 Exhibits to Declaration of Administrator

Case 2:13-cv-05693-PSG-GJS Document 686-4 Filed 04/10/17 Page 1 of 303 Page ID #:24740 Exhibit A Page 1 of 303 Case 2:13-cv-05693-PSG-GJS Document 686-4 Filed 04/10/17 Page 2 of 303 Page ID #:24741 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA NOTICE OF PENDENCY OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT A federal court authorized this notice. This notice is not an endorsement of plaintiff’s claims or an attorney solicitation. Distribution of this notice does not guarantee that you will recover money. Please read this notice carefully; it affects your legal rights. If You Are An Owner Of A Sound Recording(s) Fixed Prior To February 15, 1972 (“Pre-1972 Sound Recording”) Which Has Been Performed, Distributed, Reproduced, Or Otherwise Exploited By Sirius XM in the United States Without A License Or Authorization To Do So From August 1, 2009 Through November 14, 2016, You Could Get Benefits From a Class Action Settlement. If you are an owner of a Pre-1972 Sound Recording performed, distributed, reproduced, or otherwise exploited by Sirius XM in the United States without a license or authorization to do so from August 1, 2009 through November 14, 2016 (“Class Period”), you may be a member of a proposed nationwide Settlement Class and entitled to payments and future royalties. • If the Court approves the proposed settlement, Sirius XM will pay the Settlement Class: • $25 million for past performances, • if Sirius XM loses certain appeals, up to an additional $15 million, for a total of $40 million, for past performances, and • a royalty rate of up to 5.5% on future performances of Pre-1972 Sound Recordings owned by Settlement Class Members who make valid claims.