Osteopathic Philosophy and History 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holistic Hippocrates: 'Treating the Patient, Not Just the Disease'

King, Helen. "The Holistic Hippocrates: ‘Treating the Patient, Not Just the Disease’." Hippocrates Now: The ‘Father of Medicine’ in the Internet Age. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. 133–154. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350005921.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 04:27 UTC. Copyright © Helen King 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Th e Holistic Hippocrates: ‘Treating the Patient, N o t J u s t t h e D i s e a s e ’ I n t h i s fi nal chapter I want to look at the Hippocrates of today not through specifi c uses in news stories or in quotes, but through the invocation of his name in holistic (or, as we shall see, ‘wholistic’) medicine. Holism today presents itself as a return to a superior past, and brings Hippocrates in as part of this strategy. Th e model of the history of medicine implicit – or sometimes explicit – in holistic users of Hippocrates is one in which there was a golden age until ‘the turn away from holism in medicine allowed diseases to be located in specifi c organs, tissues or cells’.1 While there is something in this where ancient medicine is concerned, with its basis in fl uids rather than organs, this is of course also a tried and tested strategy for convincing an audience of the value of a ‘new’ thing: you claim it is ‘old’, or ancient, or just traditional. -

The Internal Environment of Animals: 32 Organization and Regulation

CHAPTER The Internal Environment of Animals: 32 Organization and Regulation KEY CONCEPTS 32.1 Animal form and function are correlated at all levels of organization 32.2 The endocrine and nervous systems act individually and together in regulating animal physiology 32.3 Feedback control maintains the internal environment in many animals 32.4 A shared system mediates osmoregulation and excretion in many animals 32.5 The mammalian kidney’s ability to conserve water is a key terrestrial adaptation ▲ Figure 32.1 How do long legs help this scavenger survive in the scorching desert heat? Diverse Forms, Common Challenges Because form and function are correlated, examining anat- omy often provides clues to physiology—biological function. he desert ant (Cataglyphis) in Figure 32.1 scavenges In the case of the desert ant, researchers noted that its stilt-like insects that have succumbed to the daytime heat of the legs are disproportionately long, elevating the rest of the ant Sahara Desert. To gather corpses for feeding, the ant 4 mm above the sand. At this height, the ant’s body is exposed Tmust forage when surface temperatures on the sunbaked sand to a temperature 6°C lower than that at ground level. The ant’s exceed 60°C (140°F), well above the thermal limit for virtually long legs also facilitate rapid locomotion: Researchers have all animals. How does the desert ant survive these conditions? found that desert ants can run as fast as 1 m/sec, close to the To address this question, we need to consider the relationship top speed recorded for a running arthropod. -

Secrets Book: (Context) I

Osteopathic Medicine David N. Grimshaw, D.O. Assistant Professor Director, Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Clinic Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine (http://www.com.msu.edu/) Department of Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine A419 East Fee Hall East Lansing, MI 48824 e-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 517-355-1740 or 517-432-6144 Fax: 517-353-0789 Pager: 517-229-2180 Secrets Book: (Context) I. General II. Therapeutic Modalities a. Mind-Body-Spirit Interventions i. Placebo and belief ii. Creative arts therapies iii. Hypnosis and Imagery iv. Meditation v. Relaxation techniques vi. Spirituality vii. Yoga b. Alternative Systems of Medical Practice i. Ayurvedic medicine ii. Traditional Oriental Medicine and Acupuncture iii. Homeopathy iv. Allopathic medicine c. Manual Healing and physical touch i. Osteopathic Medicine ii. Chiropractic iii. Massage d. Botanical Medicine e. Supplements i. Vitamins ii. Minerals iii. Bioactive compounds f. Nutrition g. Exercise, Fitness, and Lifestyle h. Energy Medicine III. Diagnostics Section IV. Special Section V. INDEX OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE 1. What is Osteopathic Medicine? Osteopathic Medicine is a branch of human medicine which was developed in the late 19th century in the United States. It is a philosophy of health care applied as a distinctive art, supported by expanding scientific knowledge. Its philosophy embraces the concept of the unity of the living organism’s structure (anatomy) and function (physiology). A frequently quoted saying of the founder of the profession, Andrew Taylor Still, is “To find health should be the object of the doctor. Anyone can find disease.” The term “Osteopathy” was chosen by Still, because “we start with the bones.” He related that osteo includes the idea of “causation” as well as “bone, ” and pathos means “suffering.” As Stefan Hagopian, DO states in an interview printed in Alternative Therapies, Nov/Dec 2001, Vol. -

CHAPTER 1 Functional Organization of the Human Body and Control of the “Internal Environment”

CHAPTER 1 Functional Organization of the Human Body and Control of the “Internal Environment” Physiology is the science that seeks to understand the function of living organisms and their parts. In human physiology, we are concerned with the characteristics of the human body that allow us to sense our environment, move about, think and communicate, reproduce, and perform all of the functions that enable us to survive and thrive as living beings. Human physiology links the basic sciences with clin- ical medicine and integrates multiple functions of mol- ecules and subcellular components, the cells, tissues, and organs into the functions of the living human being. This integration requires communication and coordina- tion by a vast array of control systems that operate at every level, from the genes that program synthesis of molecules to the complex nervous and hormonal sys- tems that coordinate functions of cells, tissues, and organs throughout the body. Life in the human being relies on this total function, which is considerably more complex than the sum of the functions of the individual cells, tissues, and organs. Cells Are the Living Units of the Body. Each organ is an aggregate of many cells held together by intercellu- lar supporting structures. The entire body contains 35 to 40 trillion cells, each of which is adapted to perform special functions. These individual cell functions are coordinated by multiple regulatory systems operating in cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems. Although the many cells of the body differ from each other in their special functions, all of them have certain basic characteristics. -

Roots Radical – Place, Power and Practice in Punk Entrepreneurship Sarah Louise Drakopoulou Dodd

Roots radical – Place, power and practice in punk entrepreneurship Sarah Louise Drakopoulou Dodd The significance continues to grow of scholarship that embraces critical and contextualized entrepreneurship, seeking rich explorations of diverse entrepreneurship contexts. Following these influences, this study explores the potentialized context of punk entrepreneurship. The Punk Rock band Rancid has a 20-year history of successfully creating independent musical and related creative enterprises from the margins of the music industry. The study draws on artefacts, interviews and videos created by and around Rancid to identify and analyse this example of marginal, alternative entrepreneurship. A three-part analytic frame was applied to analysing these artefacts. Place is critical to Rancid’s enterprise, grounding the band socially, culturally, geographically and politically. Practice also plays an important role with Rancid’s activities encompassing labour, making music, movement and human interactions. The third, and most prevalent, dimension of alterity is that of power which includes data related to dominance, subordination, exclusion, control and liberation. Rancid’s entrepreneurial story is depicted as cycles, not just a linear journey, but following more complicated paths – from periphery to centre, and back again; returning to roots, whilst trying to move forwards too; grounded in tradition but also radically focused on dramatic change. Paradox, hybridized practices, and the significance of marginal place as a rich resource also emerged from the study. Keywords: entrepreneurship; social construction; punk rock; paradox; marginality; periphery Special thanks are due to all the punks and skins who have engaged with my reading of the Rancid story, and given me so much support and feedback along the way, especially Rancid’s drummer, Branden Steineckert, Jesse from Machete Manufacturing, Kostis, Tassos (Rancid Punx Athens Crew) and Panayiotis. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Fibrosis of Two: Epithelial Cell-Fibroblast Interactions in Pulmonary Fibrosis

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1832 (2013) 911–921 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbadis Review Fibrosis of two: Epithelial cell-fibroblast interactions in pulmonary fibrosis☆ Norihiko Sakai, a,b, Andrew M. Tager a,b,c,⁎ a Center for Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA b Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA c Pulmonary and Critical Care Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA article info abstract Article history: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterized by the progressive and ultimately fatal accumulation of Received 12 December 2012 fibroblasts and extracellular matrix in the lung that distorts its architecture and compromises its function. Received in revised form 3 March 2013 IPF is now thought to result from wound-healing processes that, although initiated to protect the host Accepted 4 March 2013 from injurious environmental stimuli, lead to pathological fibrosis due to these processes becoming aberrant Available online 14 March 2013 or over-exuberant. Although the environmental stimuli that trigger IPF remain to be identified, recent evi- dence suggests that they initially injure the alveolar epithelium. Repetitive cycles of epithelial injury and re- Keywords: fi Pulmonary fibrosis sultant alveolar epithelial cell death provoke the migration, proliferation, activation and myo broblast Epithelial cells differentiation of fibroblasts, causing the accumulation of these cells and the extracellular matrix that they Apoptosis synthesize. In turn, these activated fibroblasts induce further alveolar epithelial cell injury and death, thereby Fibroblasts creating a vicious cycle of pro-fibrotic epithelial cell-fibroblast interactions. -

The Mechanics of Labor Taught by Andrew Taylor Still, M.D. by W.J

The Mechanics of Labor Taught by Andrew Taylor Still, M.D. Kirksville Missouri By W.J. Conner D.O. Kansas City, MO [RZ386.58] The Mechanics of Labor TAUGHT BY ANDRE\V TAYLOR STILL, M. D. KIRKSVILLE, MISSOURI AND Interpreted Bg w. J. CONNER, D. O. KANSAS CITY, MO. Museum of Osteopathic Medicine, Kirksville, MO THIS BOOK Is RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED To the Gro,nd A-rchitect and E'tdlder of the Universe; to Osteopaths and all other persons who believe that the first great Master Mechanic left nothing unfinishd in the machinery of his mas terpiece--MAN-that is necessary to his comfort and longevity. -A. T. STILL. Museum of Osteopathic Medicine, Kirksville, MO INTERPRETED BY DR. W. J. CONNER Introductory In writing this brief epistle, it is not the inten tion of the author to write a text book on obstetrics. I claim no originality for myse],f, just my interpreta tion of what Doctor Still taught. Like Christ, he taught much, but wrote little, especially on obstet~ rics. Having h2en inti'mately associated with him for five years, during the most a.ctive part of his life, and being in the Obstetrical Department of his . Institution, I feel competent to interpret his teach ings. When he obtained a Charter for the American School of Osteopathy, he specified that the objects Copyrighted 1928 of the school were to teach an improved system of By Surgery, Obstetrics and General Practice. DR. W. J. CONNER .. He never claimed Osteopathy to be a new science of healing, no more than did Henry Ford claim he was building a new car when he put on a self-starter. -

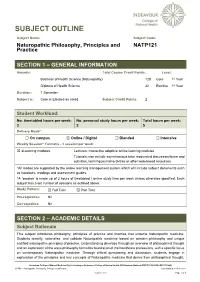

NATP121 Naturopathic Philosophy, Principles and Practice Last Modified: 18-Feb-2021

SUBJECT OUTLINE Subject Name: Subject Code: Naturopathic Philosophy, Principles and NATP121 Practice SECTION 1 – GENERAL INFORMATION Award/s: Total Course Credit Points: Level: Bachelor of Health Science (Naturopathy) 128 Core 1st Year Diploma of Health Science 32 Elective 1st Year Duration: 1 Semester Subject is: Core or Elective as noted Subject Credit Points: 2 Student Workload: No. timetabled hours per week: No. personal study hours per week: Total hours per week: 3 2 5 Delivery Mode*: ☐ On campus ☒ Online / Digital ☐ Blended ☐ Intensive Weekly Session^ Format/s - 1 session per week: ☒ eLearning modules: Lectures: Interactive adaptive online learning modules Tutorials: can include asynchronous tutor moderated discussion forum and activities, learning journal activities or other web-based resources *All modes are supported by the online learning management system which will include subject documents such as handouts, readings and assessment guides. ^A ‘session’ is made up of 3 hours of timetabled / online study time per week unless otherwise specified. Each subject has a set number of sessions as outlined above. Study Pattern: ☒ Full Time ☒ Part Time Pre-requisites: Nil Co-requisites: Nil SECTION 2 – ACADEMIC DETAILS Subject Rationale This subject introduces philosophy, principles of practice and theories that underlie Naturopathic medicine. Students identify, rationalise, and validate Naturopathic medicine based on western philosophy and unique codified naturopathic principles of practice. Understanding develops through an overview -

Osteopathic Truth Vol. 2 No. 6 January 1918

Osteopathic Truth January 1918 Vol. 2, No. 6 Reproduced with a gift from the Advocates for the American Osteopathic Association (AAOA Special Projects Fund) May not be reproduced in any format without the permission of the Museum of Osteopathic Medicine,SM [1978.257.10] MEMORIAL TO DR. ANDREW T AYLOR STILL FOUNDER OF OSTEOPATHY ~steopatbic '!rutb A MONTHLY MAGAZINE FOR THE OSTEOPATHIC PROFESSION No compromise with materia medica for therapeutic purposes Volume II JANUARY, 1918 Number 6 ~rtbute5 to tbe ~Ib mortor THE PROFESSION AS NEVER BEFORE HAS BEEN held memorial exercises. At the monthly meeting of the STIRRED BY THE PASSING OF DR. STILL Boston Society, Dec. 15th, several members present were The death of Dr. Still has stirred the osteopathic called upon for remarks and reminiscences of the Old Doc profession to its "ery depths. His passing has given rise tor. to an introspective as well as a prospective turn of mind Special funeral services were held by the A. T. Still throughout the profession. It has given rise to seL·iou. Osteopathic Association of California in the offices of Dr. contemplation on the part of all regarding the futUle of Grace 'Wyckoff, Story Building, Los Angeles, Cal., Dec. --- - 14, 1917 at 3:30 P. M. Dr. Nettie Olds Haight-Stiilgle delivered the oration which we herewith print in full: TRIBUTE TO DR. A. T. STILL On Aug. 8th, 1897, in an address before his fellow townsmen, Dr. Still said: "I am now 69 years old; next .year makes seventy. I do not expect to have many more such celebrations. -

Intro to the Fluid Course Schedule November 7-8, 2020 - Zoom

Intro to the Fluid Course Schedule November 7-8, 2020 - Zoom Course Directors: Maria T. Gentile, DO and Wendy S. Neal, DO Faculty: Eric Dolgin, DO, FCA; Kathryn Gill, MD; Bonnie Gintis, DO, FCA; Paul Lee, DO, FAAO, FCA; Mark Rosen, DO, FCA DAY 1– Saturday, Nov 7, 2020 9:00 PT L Introduction to the Fluids / Fluid Compartments overview 20 Gentile 9:20 PT L Development and Structure of the Fluid System 30 Neal 9:50 PT L The CSF 30 Dolgin 10:20 PT L Intracranial Anatomy 30 Lee 10:50 PT L Discussion in Small Groups 10 Faculty 11:00 PT L Fluids in Nature 20 Rosen 11:20 PT L The Lymphatic System 30 Gentile 11:50 PT L Faculty Q&A 15 Faculty 12:05 PT Adjourn (3:08 L) 0 All DAY 2– Sunday, Nov 8, 2020 9:00 PT L The Vascular System 30 Gill 9:30 PT L Fluids in Osteopathy 20 Rosen 9:50 PT L The Extracellular Matrix 20 Lee 10:10 PT L Fluid Motion in Life 20 Neal 10:30 PT L Discussion in Small Groups 10 10:40 PT L Other Perspectives on Fluids 20 Gintis 11:00 PT P Fluid Lab 40 Gintis 11:40 PT L Faculty Q&A 15 Faculty 11:55 PT Adjourn (2:92 L) 0 All VASCULAR SYSTEM HANDOUT K. GILL, MD 11/2020 INTRO TO THE FLUID COURSE VASCULATURE LECTURE HANDOUT: Introduction: 1. Explore the Laws creating the Form and Physiology of the Vasculature. 2. The Heart is communicating with the periphery on many different levels. -

Somatic Dysfunction? a Neurologist's Musings of Osteopathic Philosophy

8 ACOFP 55th Annual Convention & Scientific Seminars Somatic Dysfunction? A Neurologist’s Musings of Osteopathic Philosophy, Principles & Practice Joseph R. Carcione, Jr., DO, MBA 3/14/2018 Somatic Dysfunction? A Neurologist’s Musings of Osteopathic Philosophy, Principles & Practice Joseph R. Carcione, Jr, DO, MBA Board Certified, Neurology & Neuromuscular Medicine Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine & Therapy Electrodiagnostic Medicine & Diagnostic Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Medical Acupuncture www.painlogix.com Osteopathic Medicine: Where are we today? Proposal for our discussion • D.O. vs. M.D. – there still is a need to educate • Enhancement of the public’s knowledge • Physician M.D. & others understanding • Federal, State & Private Payors • Workers’ Compensation & its adjustors + ALJs • Auto insurance and Personal Injury • Third Party Administrators • Preauthorization providers • Revisiting Osteopathic Philosophy • Revisiting Osteopathic Principles & Practice • Redefine Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine • Rebrand Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy 1 3/14/2018 Preauthorization Forms in 2018: You're here because you know something. What you know, you can't explain. But you feel it. You've felt it your entire life. That there's something wrong with the world. You don't know what it is, but it's there...like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back.....You take the blue pill, the story ends. You wake up and believe...whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill.....you stay in wonderland...and I show you just how deep the rabbit hole goes…. Morpheus to Neo, in The Matrix, Released 1999 2 3/14/2018 Vignette: The Red Pill of my Osteopathic Epiphany 37 y/o right handed firefighter with no past med hx presenting with right hand & lateral arm numbness associated with weakness of his upper arm muscles.