The Holistic Hippocrates: 'Treating the Patient, Not Just the Disease'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

House of Representatives Ninety-Sixth Congress Second Session

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 'I FRAUDS AGAINST THE ELDERLY: HEALTH QUACKERY = HEARING BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON AGING HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 1, 1980 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Aging Comm. Pub. No. 96-251 \ u.s. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1980 1 1 ----~-~- --- -------- 1 1 ~ '1 , i 1 1 1 1 CONTENTS 1 MEMBERS OPENING STATEMENTS 1 Page Chairman Claude Pepper .............................................................................................. 1 1 Charles E. Grassley ........................................................................................................ 2 Don Bonker ...................................................................................................................... 3 SELECT COMMITl'EE ON AGING David W. Evans ............................................................................................................... 3 1 PPER Florida, Chairman Mary Rose Oakar ............................................................................................................ 4 ?LA"?DE PE 'CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa, Geraldine A. Ferraro ...................................................................................................... 6 1 EDWARD R ROYBAL, Cahforma Ranking Minority kfember .' 6 ~~~i:~!g~~::~~~.:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 r::~O :ttn~~\¥~e~o;:kcarolina f6~A~SL ~i~~::sc~~~~~, Arkansas -

Hippocrates: Facts and Fiction 1. Introduction

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 HIPPOCRATES: FACTS AND FICTION ABSTRACT Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, is reviewed as a historical person and in terms of his contribution to medicine in order to distinguish fact from fiction. Contem- porary and later sources reveal that many (possibly untrue) legends accumulated around this enigmatic figure. The textual tradition and the composition of the so- called Corpus Hippocraticum, the collection of medical works written mainly in the 5th and 4th centuries BC (of which possibly only about five can be ascribed to Hip- pocrates himself) are discussed. The origin of the Hippocratic Oath, and the impact of the Hippocratic legacy on modern medicine are considered. 1. INTRODUCTION This article considers the historicity of Hippocrates, the Father of Me- dicine, distinguishes fact from fiction and assesses his contribution to the discipline in the context of the many myths, which are shown by both contemporary and later sources to have arisen about this enig- matic figure. The textual transmission and compilation of the Corpus Hippocraticum, a collection of medical texts written mainly in the 5th and 4th centuries BC (of which only perhaps five can be ascribed to Hippocrates with any degree of certainty), will also be discussed. Fi- nally, the origin of the Hippocratic Oath and the value of the Hippo- cratic legacy to modern medicine will be examined. Hippocrates has enjoyed unrivalled acclaim as the Father of Medi- cine for two and a half millennia. Yet he is also an enigmatic figure, and there is much uncertainty about his life and his true contribution to medicine. -

Modern Commentaries on Hippocrates1

MODERN COMMENTARIES ON HIPPOCRATES1 By JONATHAN WRIGHT, M.D. PLEASANTVILLE, N. Y. PART I ERHAPS it is not the only way, but disturb us if Plato is thought by the young one of the ways of judging of the lady at the library to have written some excellence of a work of science or thing on astronomy or if the man who literature is to take note of the preaches in our church thinks Aristotle discussion the author has elicited in wasless a monk. We ourselves may be unable talentedP readers and the stimulation of to get up any enthusiasm for either. But the faculties thereby evidenced. In the when we learn that all these men have by conceit and braggadocio of Falstaff, aside their words tapped the ocean of thought in from his being the butt of jokes, we every era of civilization since they lived perceive he is conscious of the quality of and at their magic touch abundant streams his mind when he says he is not only witty of mental activity have gone forth to enrich himself, but is the cause of wit in others. the world, when we once realize what an There is no standard of truth whereby ever living power they still exercise over the the accuracy of theory and practice of one best minds which humanity produces, then age can be judged by another, though there what Dotty says about Ibsen or what Bill are underlying general principles which per Broker thinks of Kipling, that the Reverend sist as much perhaps by their vagueness Mr. -

The Zodiac Man in Medieval Medical Astrology

Quidditas Volume 3 Article 3 1982 The Zodiac Man in Medieval Medical Astrology Charles Clark University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Charles (1982) "The Zodiac Man in Medieval Medical Astrology," Quidditas: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol3/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Zodiac Man in Medieval Medical Astrology by Charles Clark University of Colorado A naked male figure was a familiar illustration in many medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. Standing with his legs and arms slightly spread, the twelve images or names of the zodiac were superimposed on his body, from his head (Aries) to his feet (Pisces). Used as a quick reference by physicians, barber-surgeons, and even laymen, the figure indicated the part of the body which was "ruled" by a specific sign of the zodiac. Once the correct sign was determined for the particular part of the body, the proper time for surgery, bloodletting, administration of medication, or even the cutting of hair and nails could be found. This depended, above all, upon the position of the moon in the heavens, since it was a medieval commonplace attributed to the astronomer Ptolemy (ca. 150 A.D.) that one touched neither with iron nor with medication the part of the body in whose zodical sign the moon was at that particular moment. -

Utilization of Alternative Systems of Medicine As Health Care Services in India: Evidence on AYUSH Care from NSS 2014

RESEARCH ARTICLE Utilization of alternative systems of medicine as health care services in India: Evidence on AYUSH care from NSS 2014 Shalini Rudra1☯, Aakshi Kalra2☯, Abhishek Kumar2☯, William Joe2☯* 1 Associate Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi, India, 2 Population Research Centre, Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi University North Campus, Delhi, India ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 AYUSH, an acronym for Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa and Homeopathy represents the alternative systems of medicine recognized by the Gov- ernment of India. Understanding the patterns of utilization of AYUSH care has been impor- OPEN ACCESS tant for various reasons including an increased focus on its mainstreaming and integration with biomedicine-based health care system. Based on a nationally representative health Citation: Rudra S, Kalra A, Kumar A, Joe W (2017) Utilization of alternative systems of medicine as survey 2014, we present an analysis to understand utilization of AYUSH care across health care services in India: Evidence on AYUSH socioeconomic and demographic groups in India. Overall, 6.9% of all patients seeking out- care from NSS 2014. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0176916. patient care in the reference period of last two weeks have used AYUSH services without https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176916 any significant differentials across rural and urban India. Importantly, public health facilities Editor: Gianni Virgili, Universita degli Studi di play a key role in provisioning of AYUSH care in rural areas with higher utilization in Chhat- Firenze, ITALY tisgarh, Kerala and West Bengal. -

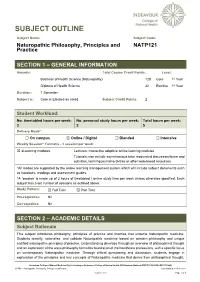

NATP121 Naturopathic Philosophy, Principles and Practice Last Modified: 18-Feb-2021

SUBJECT OUTLINE Subject Name: Subject Code: Naturopathic Philosophy, Principles and NATP121 Practice SECTION 1 – GENERAL INFORMATION Award/s: Total Course Credit Points: Level: Bachelor of Health Science (Naturopathy) 128 Core 1st Year Diploma of Health Science 32 Elective 1st Year Duration: 1 Semester Subject is: Core or Elective as noted Subject Credit Points: 2 Student Workload: No. timetabled hours per week: No. personal study hours per week: Total hours per week: 3 2 5 Delivery Mode*: ☐ On campus ☒ Online / Digital ☐ Blended ☐ Intensive Weekly Session^ Format/s - 1 session per week: ☒ eLearning modules: Lectures: Interactive adaptive online learning modules Tutorials: can include asynchronous tutor moderated discussion forum and activities, learning journal activities or other web-based resources *All modes are supported by the online learning management system which will include subject documents such as handouts, readings and assessment guides. ^A ‘session’ is made up of 3 hours of timetabled / online study time per week unless otherwise specified. Each subject has a set number of sessions as outlined above. Study Pattern: ☒ Full Time ☒ Part Time Pre-requisites: Nil Co-requisites: Nil SECTION 2 – ACADEMIC DETAILS Subject Rationale This subject introduces philosophy, principles of practice and theories that underlie Naturopathic medicine. Students identify, rationalise, and validate Naturopathic medicine based on western philosophy and unique codified naturopathic principles of practice. Understanding develops through an overview -

Elective Astrology - Timing Medical Procedures

13 13 Welcome to the 13th GATE, the domain of Ophiuchus the 13th Sign, Hygeia the Goddess of Health and Chiron the Wounded Healer. This realm is governed by the healing powers of the Universe. It is the place to come to be restored. SELECTIONS: Stellar Healing, Cosmic Apothecary, Crystal Therapy Primer, Healing with Hygeia, Chiron and Ophiuchus. __________________________________________________________________ STELLAR HEALING Holistic Astrology and Astral-Geo Therapy STARLOGIC ASTRODYNAMICS AND STELLAR HEALING A question often posed by a client is, “What does my chart reveal about my health?” Health Astrology is a sub division of Medical Astrology that embraces a homeopathic and holistic view. An individual natal chart reveals certain predisposition for “dis-ease” that has the propensity to develop over a lifetime. Environmental factors, improper diet, or simply a lack of knowledge regarding possible deficiencies can all contribute to the onset of health problems. A natal chart actually yields a nutritional plan specific to the native by indicating the need for minerals and vitamins that can be beneficially instrumental in maintaining a healthy body. The association between bodily illness and the signs and planets of the Zodiac belong to the Hermetic Theory which is an ancient Egyptian/Greek philosophical science. Hermetic Theory is based on the premise that the entire Cosmos is reflected in each human being. In this system, the signs and degrees of the Zodiac correlate to human anatomy and the planets to the physical and chemical processes and to specific organ malfunction and vitamin and mineral deficiencies. The Uranian planets, Hades, Admetos, Appollon, and applicable Fixed Stars are also used in analysis. -

SUMMER SCHOOL 16Th – 23Rd August 2013 ~ Exeter College, Oxford

SUMMER SCHOOL 16th – 23rd August 2013 ~ Exeter College, Oxford Guest Tutors: Bernadette Brady | Nicholas Campion | Geoffrey Cornelius Darby Costello | Maggie Hyde | Karen Parham | Melanie Reinhart | Sue Tompkins Faculty Tutors: Laura Andrikopoulos | Cat Cox | Penny De Abreu | Kim Farley Deborah Morgan | Glòria Roca | Carole Taylor | Dragana Van de Moortel-Ilić | Polly Wallace Raising the standard of astrological education since 1948 THE FACULTY’S ANNUAL SUMMER SCHOOL The Faculty’s annual Summer School is one of the world’s best-known astrological events, attracting students from many countries to the beautiful city of Oxford to enjoy the weekend and five-day courses. The programme caters for a range of levels, from relative beginners through to students and practitioners at advanced or professional level. With our world class team of experienced guest tutors providing an exciting and dynamic programme of study, Summer School offers you a chance to work in depth with astrology, developing knowledge of new subjects and techniques, and deepening your understanding of existing ones. The Faculty will do its very best to make you feel welcome and at home. Our conference team ensures the smooth running of the School, leaving you free to sit back and enjoy the astrology, community atmosphere and the beauty of Exeter College. EXETER COLLEGE Exeter College was founded in 1314 and stands in the heart of Oxford near to the Bodleian Library. The oldest part of the college dates to 1432, with other buildings added in the 17th and 18th centuries, including the Gothic chapel with its magnificent stained glass and a stunning Jacobean dining hall. -

Thales of Miletus Hippocrates I Replaced Superstition with Science. I

® Name: ____________________ Lesson # 1: Crosscutting Concepts in Science hb g7fcj 1. Scientists observe, question, 2. Science gives us a language 3. Patterns can demonstrate a investigate, and seek to to communicate information cause-and-effect relationship. understand our universe. about phenomena and patterns. Causation means a caused b. Explanations and descriptions often require empirical data. Which phenomena below Macroscopic to microscopic Empirical means… means… demonstrate causation? Every time I theories to evidence-based. wash my car, it data. rains. hair features beard/cloak Helium rises so very large to abstract. my helium balloon very small. floats. hair features beard/cloak 4. Scientific data sometimes 5. Causation – a clear link 6. Correlation - a relationship shows a correlation or showing something directing that you see between two association between causes something else to occur. factors or conditions that may observations or phenomena. appear to be related. Which events demonstrate a Find an example of causation Find an example of a correlation? below. correlation below. The more you I didn’t step on any cracks in the I think waffles taste better with study, the better sidewalk, so my mom didn’t melted butter and your grades. break her back. blueberries. eclipse icon magnet olives Combining 2 primary Pushing the brake People who watch lots colors results in made the car stop. of television eat lots a secondary color. of junk food. magnet eclipse icon olives 7. My dog barks for a few 8. Grandma drinks fresh 9. My brother is allergic to minutes every night. My orange juice almost every wool. If he wears something neighbor always takes an morning and she is rarely sick. -

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine for Students, by Students

A Brief Guide to Osteopathic Medicine For Students, By Students By Patrick Wu, DO, MPH and Jonathan Siu, DO ® Second Edition Updated April 2015 Copyright © 2015 ® No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine 5550 Friendship Boulevard, Suite 310 Chevy Chase, MD 20815-7231 Visit us on Facebook Please send any comments, questions, or errata to [email protected]. Cover Photos: Surgeons © astoria/fotolia; Students courtesy of A.T. Still University Back to Table of Contents Table of Contents Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Myth or Fact?....................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 1: What is a DO? ..............................................................................................................................