Insect Poetics Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Check List of Noctuid Moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae And

Бiологiчний вiсник МДПУ імені Богдана Хмельницького 6 (2), стор. 87–97, 2016 Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University, 6 (2), pp. 87–97, 2016 ARTICLE UDC 595.786 CHECK LIST OF NOCTUID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE AND EREBIDAE EXCLUDING LYMANTRIINAE AND ARCTIINAE) FROM THE SAUR MOUNTAINS (EAST KAZAKHSTAN AND NORTH-EAST CHINA) A.V. Volynkin1, 2, S.V. Titov3, M. Černila4 1 Altai State University, South Siberian Botanical Garden, Lenina pr. 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology, Lenina pr. 36, 634050, Tomsk, Russia 3 The Research Centre for Environmental ‘Monitoring’, S. Toraighyrov Pavlodar State University, Lomova str. 64, KZ-140008, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan. E-mail: [email protected] 4 The Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Prešernova 20, SI-1001, Ljubljana, Slovenia. E-mail: [email protected] The paper contains data on the fauna of the Lepidoptera families Erebidae (excluding subfamilies Lymantriinae and Arctiinae) and Noctuidae of the Saur Mountains (East Kazakhstan). The check list includes 216 species. The map of collecting localities is presented. Key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Erebidae, Asia, Kazakhstan, Saur, fauna. INTRODUCTION The fauna of noctuoid moths (the families Erebidae and Noctuidae) of Kazakhstan is still poorly studied. Only the fauna of West Kazakhstan has been studied satisfactorily (Gorbunov 2011). On the faunas of other parts of the country, only fragmentary data are published (Lederer, 1853; 1855; Aibasov & Zhdanko 1982; Hacker & Peks 1990; Lehmann et al. 1998; Benedek & Bálint 2009; 2013; Korb 2013). In contrast to the West Kazakhstan, the fauna of noctuid moths of East Kazakhstan was studied inadequately. -

Nota Lepidopterologica, 25.04.2012, ISSN 0342-7536 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; Download Unter Und

©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Nota lepi. 35(1): 33-50 33 Additions to the checklist of Bombycoidea and Noctuoidea of the Volgo-Ural region. Part II. (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae, Erebidae, Nolidae, Noctuidae) Kari Nupponen ' & Michael Fibiger"^ Merenneidontie 19 D, FI-02320 Espoo, Finland; [email protected] ^ Deceased. 1 1 Received May 20 1 1 ; reviews returned September 20 1 ; accepted 3 December 2011. Subject Editor: Lauri Kaila. Abstract. Faunistic records additional to the recently published lists of Bombycoidea and Noctuoidea of the South Ural Mountains (Nupponen & Fibiger 2002, 2006) are presented, as well as some interesting records from the North Urals and the Lower Volga region. The material in the southern Urals was collected during 2006-2010 in six different expeditions, in North Ural in 2003 and 2007, and in the Lower Volga region in 2001, 2002, 2005, and 2006 in four expeditions. Four species are reported for the first time from Europe: Dichagyris latipennis (Piingeler, 1909), Pseudohermonassa melancholica (Lederer, 1853), Spae- lotis deplorata (Staudinger, 1897), and Xestia albonigra (Kononenko, 1981). Fourteen species are reported for the first time from the southern Urals. Altogether, records of 68 species are reported, including a few corrections to the previous articles. Further illustrations and notes on some poorly known taxa are given. Introduction The fauna of Bombycoidea and Noctuoidea of the southern Ural Mountains has been studied intensely since 1996, and the results of the research during 1996-2005 were published by Nupponen & Fibiger (2002, 2006). Since 2005, several further expedi- tions were made to the Urals by the first author. -

Scottish Macro-Moth List, 2015

Notes on the Scottish Macro-moth List, 2015 This list aims to include every species of macro-moth reliably recorded in Scotland, with an assessment of its Scottish status, as guidance for observers contributing to the National Moth Recording Scheme (NMRS). It updates and amends the previous lists of 2009, 2011, 2012 & 2014. The requirement for inclusion on this checklist is a minimum of one record that is beyond reasonable doubt. Plausible but unproven species are relegated to an appendix, awaiting confirmation or further records. Unlikely species and known errors are omitted altogether, even if published records exist. Note that inclusion in the Scottish Invertebrate Records Index (SIRI) does not imply credibility. At one time or another, virtually every macro-moth on the British list has been reported from Scotland. Many of these claims are almost certainly misidentifications or other errors, including name confusion. However, because the County Moth Recorder (CMR) has the final say, dubious Scottish records for some unlikely species appear in the NMRS dataset. A modern complication involves the unwitting transportation of moths inside the traps of visiting lepidopterists. Then on the first night of their stay they record a species never seen before or afterwards by the local observers. Various such instances are known or suspected, including three for my own vice-county of Banffshire. Surprising species found in visitors’ traps the first time they are used here should always be regarded with caution. Clerical slips – the wrong scientific name scribbled in a notebook – have long caused confusion. An even greater modern problem involves errors when computerising the data. -

(FDACS) Final Performance Report USDA AMS AGREEMENT NUMBER

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & CONSUMER SERVICES (FDACS) Final Performance Report 2011 SPECIALTY CROP BLOCK GRANT PROGRAM FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE & CONSUMER SERVICES USDA AMS AGREEMENT NUMBER: 12-25-B-1221 TOTAL GRANT FUNDS AWARDED - $4,385,464.97 STATE CONTACT Joshua M. Johnson Program Administrator Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services 407 South Calhoun Street Room 415B Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0800 (850) 617-7340 [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Project (1): University of Florida - Temik Replacement for Optimized prefumigation irrigation to enhance soil borne nematodes & disease control in Florida potatoes 3 Project (2): University of Florida - Mitigation and chemical control of the RedBay Ambrosia Beetle in Florida Avocado 9 Project (3): University of Florida - Development Strategies for Root-Knot nematodes on Cut Foliage and Ornamental Crops 27 Project (4): University of Florida - Effect of Nitrogen Rate and Application Method on Peach Tree Growth and Fruit Quality 31 Project (5): Florida Specialty Crop Foundation - Groundnut Ringspot Virus, an emerging thrips- transmitted virus infecting Florida tomato, pepper and other specialty crops 38 Project (6): University of Florida - Use of Fallow Weed Control Program to Reduce Yellow and Purple Nutsedge Population in Bell Pepper 47 Project (7): Florida Specialty Crop Foundation - Improved Bacterial Spot Management for FL tomato production using bactericides & improved application strategies 51 Project (8): USDA-ARS - Development and -

Archanara Neurica (Hübner, 1808) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) New to Norway

© Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 25 June 2012 Archanara neurica (Hübner, 1808) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) new to Norway LEIF AARVIK & JAN ERIK RØER Aarvik, L. & Røer, J.E. 2012. Archanara neurica (Hübner, 1808) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) new to Norway. Norwegian Journal of Entomology 59, 1–4. The noctuid moth Archanara neurica (Hübner, 1808) is reported new to Norway. In 2008 a few specimens were collected in Farsund in southernmost Norway. Notes on the distribution, external characters, biology and habitat are given. Key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Archanara neurica, Norway, distribution, biology. Leif Aarvik, Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1172 Blindern, NO-0318 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]’ Jan Erik Røer, Lista Bird Observatory, Fyrveien 6, NO-4563 Borhaug, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction 2000). We herewith report the second European Archanara species, A. neurica (Hübner, 1808), as The genus Archanara Walker, 1866 belongs to new to Norway. a group of genera with strong ecological affinity to moist habitats. The group was termed the Rhizedra genus-group by Zilli et al. (2005), and The records the following species are recorded from Norway; Fabula zollikoferi (Freyer, 1836), Rhizedra lutosa In 2010 the authors were shown a photo of a (Hübner, 1803), Nonagria typhae (Thunberg, moth collected at Lista Fyr on 11 August 2010 1794), Arenostola phragmitidis (Hübner, 1803), by Richard Cope (Figure 1). The collector had Longalatedes elymi (Treitschke, 1825) and photographed the specimen and later released Archanara dissoluta (Treitschke, 1825) (Aarvik et it. After some discussion it was concluded that al. 2000, Zilli et al. -

Lepidoptera) of the Western Kazakhstan

© Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 37, Heft 39: 597-616 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. April 2016 To Research of Noctuoidea Fauna (Lepidoptera) of the Western Kazakhstan Dmitry F. SHOVKOON & Tatiana A. TROFIMOVA Abstract Noctuoidea fauna of the Western Kazakhstan was examined by authors from 2003 to 2012. As a result of this study the annotated list includes 200 species. The species Rhabinopteryx turanica (ERSCHOFF, 1874), Heptapotamia eustratii ALPHÉRAKY, 1882, Eugnorisma tamerlana (HAMPSON, 1903) and Margelana versicolor (STAUDINGER, 1888) are noted here as new for Europe. Guselderia lutea HACKER, KUHNA & GROSS, 1986 (nov. syn.) is established as a junior synonym of Heptapotamia eustratii ALPHÉRAKY, 1882. 573 species of Noctuoidea known at present from the Western Kazakhstan are discussed. Key words: Western Kazakhstan, Noctuoidea fauna. Zusammenfassung Die Noctuoidea Fauna von West-Kasachstan wurde von den Autoren in den Jahren 2003 bis 2012 erforscht. Als Ergebnis wird hier eine Liste mit 200 Arten vorgestellt. Rhabinopteryx turanica (ERSCHOFF, 1874), Heptapotamia eustratii ALPHÉRAKY, 1882, Eugnorisma tamerlana (HAMPSON, 1903) und Margelana versicolor (STAUDINGER, 1888) sind Erstnachweise für Europa. Guselderia lutea HACKER, KUHNA & GROSS, 1986 (nov. 597 Shovkoon_To Research of Noctuoidea Fauna_Z0.indd 1 13.04.16 09:35 © Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at syn.) wird als jüngeres Synonym zu Heptapotamia eustratii ALPHÉRAKY, 1882 gestellt. Die insgesamt 573 derzeit aus West Kazakhstan bekannten Noctuoidea Arten werden diskutiert. Introduction The Noctuoidea of the European region is well-known as soon as the last volume of a series devoted to the particular part of the regional fauna (Noctuidae Europaeae) was finished in 2011. -

Dumfries & Galloway Local Biodiversity Action Plan

Dumfries & Galloway Local Biodiversity Action Plan Written and edited by Peter Norman, Biodiversity Officer, with contributions from David Hawker (Flowering Plants Species Statement), Nic Coombey (Geodiversity & Traditional Orchards) and Clair McFarlan (Traditional Orchards). Designed by Paul McLaughlin, Dumfries and Galloway Council Printed by Alba Printers Published by Dumfries & Galloway Biodiversity Partnership, April 2009 Production of this LBAP has been made possible through funding by Acknowledgements Thank-you to all members of the Dumfries & Galloway Biodiversity Partnership Steering Group and Habitat Working Groups, especially Chris Miles of SNH, Alastair McNeill of SEPA, Chris Rollie of RSPB and Sue Bennett of DGC. Thanks also to Liz Holden for invaluable assistance with all things fungal and Andy Acton for advice on lichens. Numerous publications were consulted during preparation of this plan but in the interests of brevity and readibility individual comments are not referenced. Galloway and the Borders by the late Derek Ratcliffe and The Flora of Kirkcudbrightshire by the late Olga Stewart were particularly useful sources of information. Valuable discussions/comments also received from David Hawker, Jim McCleary, Richard Mearns, Anna White and the Dumfries & Galloway Eco-Schools Steering Group. Assistance with proof-reading from Stuart Graham, Chris Miles, Fiona Moran, Mark Pollitt and Chris Rollie. Photographs Thank-you to all photographers who allowed free use of several images for this document: Greg Baillie, Gavin Chambers, Gordon McCall, Maggi Kaye, Paul McLaughlin, Richard Mearns and Pete Robinson. Other photographs were provided by the editor and partners. All images are individually credited. Additional photography: Laurie Campbell www.lauriecampbell.com, Paul Naylor www.marinephoto.org.uk, Steven Round www.stevenround-birdphotography.com, John Bridges www.northeastwildlife.co.uk . -

Virginia's Precious Heritage

Virginia’s Precious Heritage A Report on the Status of Virginia’s Natural Communities, Plants and Animals, and a Plan for Preserving Virginia’s Natural Heritage Resources Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Natural Heritage Program Virginia’s Precious Heritage: A Report on the Status of Virginia’s Natural Communities, Plants, and Animals, and a Plan for Preserving Virginia’s Natural Heritage Resources A project of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Produced by: Virginia Natural Heritage Program 217 Governor Street Richmond, Virginia 23219 This report should be cited as follows: Wilson, I.T. and T. Tuberville. 2003. Virginia’s Precious Heritage: A Report on the Status of Virginia’s Natural Communities, Plants, and Animals, and a Plan for Preserving Virginia’s Natural Heritage Resources. Natural Heritage Technical Report 03-15. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage, 217 Governor Street, 3rd Floor, Richmond, Virginia. 82 pages plus appendices. Dear Fellow Virginians: Most of us are familiar with Virginia’s rich cultural heritage. But Virginia also has an incredibly diverse and precious natural heritage – a heritage that preceded and profoundly influenced our culture and is essential to our future. We share the Old Dominion with more than 32,000 native species of plants and animals. They carpet our hills and valleys with green, they swim in our rivers and lurk in our deepest caves. A few play obviously important roles in our economy, such as the tree species that support our forest products industry, and the fishes and shellfish that are essential to the Chesapeake Bay’s seafood businesses. -

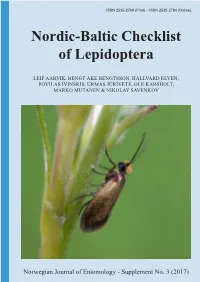

Nordic-Baltic Checklist of Lepidoptera

Supplement no. 3, 2017 ISSN 2535-2768 (Print) – ISSN 2535-2784 (Online) ISSN XXXX-YYYY (print) - ISSN XXXX-YYYY (online) Nordic-Baltic Checklist of Lepidoptera LEIF AARVIK, BENGT ÅKE BENGTSSON, HALLVARD ELVEN, POVILAS IVINSKIS, URMAS JÜRIVETE, OLE KARSHOLT, MARKO MUTANEN & NIKOLAY SAVENKOV Norwegian Journal of Entomology - Supplement No. 3 (2017) Norwegian JournalNorwegian of Journal Entomology of Entomology – Supplement 3, 1–236 (2017) A continuation of Fauna Norvegica Serie B (1979–1998), Norwegian Journal of Entomology (1975–1978) and Norsk entomologisk Tidsskrift (1921–1974). Published by The Norwegian Entomological Society (Norsk entomologisk forening). Norwegian Journal of Entomology appears with one volume (two issues) annually. Editor (to whom manuscripts should be submitted). Øivind Gammelmo, BioFokus, Gaustadalléen 21, NO-0349 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]. Editorial board. Arne C. Nilssen, Arne Fjellberg, Eirik Rindal, Anders Endrestøl, Frode Ødegaard og George Japoshvili. Editorial policy. Norwegian Journal of Entomology is a peer-reviewed scientific journal indexed by various international abstracts. It publishes original papers and reviews on taxonomy, faunistics, zoogeography, general and applied ecology of insects and related terrestial arthropods. Short communications, e.g. one or two printed pages, are also considered. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor. All papers in Norwegian Journal of Entomology are reviewed by at least two referees. Submissions must not have been previously published or copyrighted and must not be published subsequently except in abstract form or by written consent of the editor. Membership and subscription. Requests about membership should be sent to the secretary: Jan A. Stenløkk, P.O. Box 386, NO-4002 Stavanger, Norway ([email protected]). -

E-Acta Naturalia Pannonica 6: 17–44

e-Acta Naturalia Pannonica 6: 17–44. (2013) 17 A Nonagria zollikoferi Freyer, 1836 magyar története The Hungarian history of Nonagria zollikoferi Freyer, 1836 (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Bálint Zsolt & Benedek Balázs Abstract: The Hungarian history of Nonagria zollikoferi Freyer, 1836 (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). – The type locality of Nonagria zollikoferi is clarified using archive data. Two syntypic specimens detected in the Hungarian Natural History Museum are documented with other material of Fabu- la zollikoferi originating from the Carpathian Basin (captured by Dahlström in 1898: n =1; cap- tured by Nyírő in 1968: n = 2), Russia (collection Diószeghy: no = 1.; collection Bartha: n = 2) and Mongolia (collection Hreblay: n = 1). All the Hungarian records (n = 7) are discussed in details and placed in the light of recent knowledge about the life history and distribution of the species. The Hungarian vernacular names given to the moth are also reviewed. Key words: Budapest, faunistics, Imre Frivaldszky, Fabula zollikoferi, Hungary, Hungarian Natu- ral History Museum, Kazakhstan, Albert Kindermann, Mongolia, Noctuidae, Ofen, Phragmatis, Russia, syntype, Friedrich Treitschke, type locality. Authors’ address – A szerzők címe: Bálint Zsolt, Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum, 1088 Budapest VIII., Baross utca 13., Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] │ Benedek Balázs, 2045 Tö- rökbálint, Árpád u. 53., Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Summary: The species Fabula zollikoferi (Freyer, 1836) Zilli, Ronkay & Fibiger, 2005 has been described on the basis at least two syntype specimens collected by Albert Kindermann, but there was no indication about the material’s place of origin. On the basis of Imre Frivaldszky’s manu- script, most probably written before 1848, caterpillars were found in the hills of „Ofen” (= Buda; now western part of Budapest) (Fig.