Non-Francophone French Second Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Mission at Dublin School, We Strive to Awaken a Curiosity for Knowledge and a Passion for Learning

The Dubliner The Dublin School P.O. Box 522 18 Lehmann Way Dublin, New Hampshire 03444 www.dublinschool.org Address service requested Dubliner Our Mission At Dublin School, we strive to awaken a curiosity for knowledge and a passion for learning. We instill the values of discipline and meaningful work that are necessary for the good of self and community. We respect the individual learning style and unique potential each student brings to our School. With our guidance, Dublin students become men and women who seek truth and act with courage. The Fall 2014 DublinerThe Magazine of Dublin School “Involve me and I will understand.” • A View Without a Room • The Rock Garden • Looking Back with No Regrets fall 2014 1 Dubliner Dublin School Graduation—The Class of 2014 First Row: Blythe Lawrence, Pembroke Bermuda (Gemology Institute of America, London), Mylisha Drayton, Endicott, NY (Clark University, MA), Yiran Ouyang, Shenzhen China (Wesleyan University, CT), Stephanie Figueroa, Lawrence, MA (Middlesex Community College, MA), Riley Jacobs, Dayton, OH (Ohio University), Mekhi Crooks, Brooklyn, NY (Emmanuel College, MA), Molly Witten, Bethesda, MD (Wheaton College, MA), Atsede Assayehgen, Cambridge, MA (Barnard College, NY), Anna Sigel, Manchester, NH (Wheelock College, MA) Anna Rozier, Westport, CT (St. Olaf College, MN) Alyssa Jones, Jaffrey, NH (Mt. Holyoke, MA)Molly Forgaard, Hollis, NH (Bennington College, VT) Middle Row: Zhiyu Pan, Shanghi, China (Emory University, GA) Dong Min Sun, Seoul Korea (School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL) -

Finding Aid : GA 85 Alice Munro/Walter Martin Reference Materials

Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library Finding Aid : GA 85 Alice Munro/Walter Martin reference materials. © Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library GA 85 : Munro/Martin Reference Materials. Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library. Page 1 GA 85 : Munro/Martin Reference Materials Alice Munro/Walter Martin reference materials. - 1968-1994 (originally created 1950- 1994). - 1 m of textual records. - 3 audio cassettes. The collection consists primarily of photocopied material used and annotated by Dr. Walter Martin for his book Alice Munro: Paradox and Parallel published in 1987 by the University of Alberta Press. This includes articles written by Alice Munro, short stories, interviews, biographical and critical articles, as well as paperback copies of her books. Also present is a photocopied proof copy of of Moons of Jupiter, a collection of short stories by A. Munro published by Macmillan of Canada in 1982, sent to Dr. Martin by Douglas Gibson of Macmillan. Additional material includes audio recordings of Alice Munro reading her own works and of an interview done with her by Peter Gzowski for “This Country in the Morning.” The collection is arranged in 5 series: 1. Works by Alice Munro: Published; 2. Works by Alice Munro: Manuscripts (Proofs); 3. Works About Alice Munro; 4. Sound Recordings; 5. Miscellaneous. Title from original finding aid. The Alice Munro collection was donated to Special Collections in 1987 by Dr. Walter Martin of the University of Waterloo Department of English. Finding aid prepared in 1993; revised 1994, 1998 and again in 2010. Several accruals have been made since the initial donation. Series 1 : Works by Alice Munro: Published Works by Alice Munro : published. -

In the Battle for Reality (PDF)

Showcasing and analyzing media for social justice, democracy and civil society In the Battle for Reality: Social Documentaries in the U.S. by Pat Aufderheide Center for Social Media School of Communication American University December 2003 www.centerforsocialmedia.org Substantially funded by the Ford Foundation, with additional help from the Phoebe Haas Charitable Trust, Report available at: American University, and Grantmakers www.centerforsocialmedia.org/battle/index.htm in Film and Electronic Media. 1 Acknowledgments The conclusions in this report depend on expertise I have Events: garnered as a cultural journalist, film critic, curator and International Association for Media and academic. During my sabbatical year 2002–2003, I was able to Communication Research, Barcelona, conduct an extensive literature review, to supervise a scan of July 18–23, 2002 graduate curricula in film production programs, and to conduct Toronto International Film Festival, three focus groups on the subject of curriculum for social September 7–13, 2002 documentary. I was also able to participate in events (see sidebar) and to meet with a wide array of people who enriched Pull Focus: Pushing Forward, The National this study. Alliance for Media Arts and Culture conference, Seattle, October 2–6, 2002 I further benefited from collegial exchange with the ad-hoc Intellectual Property and Cultural Production, network of scholars who also received Ford grants in the same sponsored by the Program on Intellectual time period, and from interviews with many people at -

EXCAVATING the SLUSH PILE at Mcclelland & Stewart

EXCAVATING THE SLUSH PILE At McClelland & Stewart by Trena Rae White Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 2000 PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLISHING In the Master of Publishing Program of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences © Trena White, 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Trena Rae White Degree: Master of Publishing Title of Project: Excavating the Slush Pile at McClelland & Stewart Examining Committee: Rowland Lorimer Senior Supervisor Director, Master of Publishing Program Craig Riggs Supervisor Faculty, Master of Publishing Program Susan Renouf Industry Supervisor Vice-President & Associate Publisher, Non-Fiction McClelland & Stewart Date Approved: ii SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

Writing for the Reluctant Reader Losing Her Voice: a Writer

WRITE THE MAGAZINE OF THE WRITERS’ UNION OF VOLUME 42 NUMBER 3 CANADA WINTER 2015 Writing for the Reluctant Reader 8 Losing Her Voice: A Writer Struggles with a First Novel and a Dying Sister 10 The Authors’ Fest: Tips and Tricks From a Festival Insider 15 tbooks by Vivek 3 Shraya � CResidencies for Creative SHE OF THE MOUNTAINS A Globe and Mail “Globe 100” of 2014 and Cultural Exploration “A lyrical ode to love in all its many forms.” Creative spaces and —Publishers Weekly accommodation in a community and heritage setting Artists • Writers • Cultural Researchers GOD LOVES HAIR A Quill and Quire Best Book of 2014 “A moving and ultimately joyous portrait of growing up and the resiliency of youth.” 3401 Pleasant Valley Road —Canadian Children’s Book Centre Vernon, British Columbia, Canada V1T 4L4 arsenal pulp press arsenalpulp.com 250-275-1525 www.caetani.ca JOIN A HEALTH PLAN THAT’S EXCLUSIVE TO THE CANADIAN THE PLAN IS A SERVICE OF AFBS, A NOT-FOR-PROFIT INSURER WRITING COMMUNITY. IT’S EASY TO UNDERSTAND, AND COVERAGE IS GUARANTEED. CALL 1-800-387-8897 EXT. 238 OR EMAIL [email protected] TO LEARN MORE. From the Chair By Harry Thurston We are trying something new this winter in adapting our operations to the Digital Age. Instead of bringing National Council members together in Toronto for our January meeting, colleagues of the need for action, and to do so he needs the numbers. To that end we will be circulating an income survey in from all corners of this vast, snowbound country, the New Year to make our case for just how much worse things we are going to conduct our business remotely. -

HOT NEWS Is... Reinhardt University

MAGAZINEReinhardt Volume 16, No. 1 Fall 2010 Reinhardt has extra excitement this fall! Reinhardt MAGAZINE Fall 2010 classes began with more students than ever before, 1229 to be exact! President 822 are traditional students taking courses in Waleska with 475 living on campus, 133 receiving music Dr. J. Thomas Isherwood scholarships, 230 receiving athletic scholarships and 340 receiving academic scholarships. This record- Vice President for Institutional 33 Advancement & External Affairs setting student body also includes 407 nontraditional students at outreach programs for working JoEllen Bell Wilson ’61 adults in Alpharetta, Cartersville, Marietta and Epworth. Another 119 are graduate Production/Photography Staff students studying business, education, or music; 130 are in the WAIT program (our evening baccalaureate Marsha S. White* Executive Director of Marketing degree in early childhood education); and we will train more than 100 students in our police academy in and Communications Alpharetta during the 2010-11 academic year. Lauren H. Thomas* 5 Media Relations Coordinator 11 Amanda L. Brown* Graphic Designer Features Now a comprehensive university Steven P. Ruthsatz* The small college you cherish has developed into a comprehensive university Assistant Athletic Director Reinhardt is Hot News! vital to the educational stability of not only our region, but the state of Georgia. 2 Find out how Reinhardt students, alumni, community members, We now have more than 40 undergraduate degree programs, 3 master degree Jennifer Wiggins Matthews ’90 faculty and staff joined together to celebrate the beginning of a new programs, and more to come. Your Reinhardt has taken its rightful place as an Director of Alumni chapter in Reinhardt’s history. -

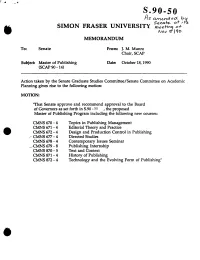

S .9050 As Amejidect B 6Emaj-E O*.' SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY ,, - S Nov MEMORANDUM

S .9050 As amejidect b 6eMaJ-e_ O*.' SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY ,, - S Nov MEMORANDUM To: Senate From: J. M. Munro Chair, SCAP Subject: Master of Publishing Date: October 18, 1990 (SCAP 90- 14) Action taken by the Senate Graduate Studies Committee/Senate Committee on Academic Planning gives rise to the following motion: MOTION: "That Senate approve and recommend approval to the Board of Governors as set forth in S.90 -50 , the proposed Master of Publishing Program including the following new courses: CMNS 670-4 Topics in Publishing Management CMNS 671 -4 Editorial Theory and Practice CMNS 672-4 Design and Production Control in Publishing S - CMNS 677-4 Directed Studies CMNS 678-4 Contemporary Issues Seminar CMNS 679 -8 Publishing Internship CMNS 870-5 Text and Context CMNS 871 -4 History of Publishing CMNS 872-4 Technology and the Evolving Form of Publishing" 46 SiMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SCM MEMORANDUM o .......... A.11i.son pay .From ...... W SenateCoitte mm eon Academic Senate Graduate Studies Committee Planning Subject..9. .... I Date.......p. The attached proposed Master of Publishing Program was approved by the Senate Graduate Studies Committee at its Meeting on September 24, 1990, and is now being forwarded to the Senate Committee on Academic Planning for approval. S>Y) )L/ mm! attach. 0 'S SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY MEMORANDUM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES is TO: Senate Graduate Studies FROM: B.P. Clayman Committee SUBJECT: MASTER OF PUBLISHING DATE: 31 August 1990 PROPOSAL I am pleased to present the proposal submitted by the Faculty of Applied Sciences for the introduction of a Master of Publishing program. -

Download Pdf Here

ISSUE 128 SUMMER 2018 ISSN 0965-1128 (PRINT) ISSN 2045-6808 (ONLINE) THE MAGAZINE OF THE SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY Sex through the ages: an endocrine perspective Special features PAGES 6–17 For mutual benefit MENTORS & MENTEES P18–19 Endocrine inspiration INVESTING IN THE FUTURE P20–21 COLIN FARQUHARSON GET SET FOR GLASGOW JANET LEWIS Meet the new Co-Editor-in- SfE BES 2018 comes to town Award-winning nurse Chief of two Society journals P23 P28 P22 www.endocrinology.org/endocrinologist WELCOME Editor: Dr Amir Sam (London) Associate Editor: Dr Helen Simpson (London) A word from Editorial Board: Dr Douglas Gibson (Edinburgh) Dr Louise Hunter (Manchester) THE EDITOR… Dr Lisa Nicholas (Cambridge) Managing Editor: Eilidh McGregor Sub-editor: Caroline Brewser Design: Ian Atherton, Corbicula Design Society for Endocrinology 1600 Bristol Parkway North Things are hotting up! Welcome to this summer issue dedicated to ‘Sex through the ages’. Bristol BS34 8YU, UK Tel: 01454 642200 When encouraging students to pursue a scientific and/or clinical career in endocrinology, I often Email: [email protected] Web: www.endocrinology.org tell them that endocrine science and practice span the entire human life cycle, making endocrinology Company Limited by Guarantee the most vibrant, inclusive and fascinating discipline in medicine. The field of reproductive Registered in England No. 349408 Registered Office as above endocrinology has witnessed exciting advances over recent years, and it is wonderful to see UK Registered Charity No. 266813 scientists and clinicians continuing to play a major role in ground-breaking developments. ©2018 Society for Endocrinology The views expressed by contributors The feature articles in this issue of The Endocrinologist cover many topical issues in this area. -

TITLE Section SECTION AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR Breaking Down the Wall of Silence: the Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth

TITLE Section SECTION AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR Breaking Down the Wall of Silence: The Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth AB Abuse Miller, Alice Meridian Books 1993 Growth Seasons: Overcoming Your Abusive Past AB Abuse Craig, James D. Crossroads Christian Communications, Inc. 1993 Healing the Incest Wound: Adult Survivors in Therapy AB Abuse Courtois, Christine A. W. W. Norton & Company 1988 If I'd Only Known AB Abuse Neddermeyer, Dorothy M. Millennial Mind Publishing 2000 The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse (2 copies) AB Abuse Bass, Ellen & Davis, Laura Harper & Row, New York 1988 The Courage to Heal Workbook: For Women and Men Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse AB Abuse Davis, Laura Harper & Row, New York 1990 The Right of Innocence: Healing the Trauma of Childhood Sexual Abuse AB Abuse Engel, Beverly Ivy Books 1989 The Sexual Healing Journey: A Guide for Survivors of Sexual Abuse AB Abuse Maltz, Wendy Harper Perennial 1991 The Survivor's Guide to Sex: How to Have an Empowered Sex Life After Childhood Sexual Abuse AB Abuse Haines, Staci Cleis Press Inc. 1999 Wednesday's Children: Adult Survivors of Abuse Speak Out AB Abuse Somers, Suzanne HealingVision, Inc. 1992 When You're Ready: A woman's healing from childhood physical and sexual abuse by her mother AB Abuse Evert, Kathy & Bijerk, Inie Launch Press 1987 A Million Little Pieces AD Addictions Frey, James Anchor Books 2003 About Cocaine (For Reference Only) AD Addictions Addiction Research Foundation Addiction Research Foundation (ARF) 1997 Herie, Marilyn, Godden, Tim, Shenfeld, Joanne & Kelly, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Addiction: An Information Guide AD Addictions 2010 Colleen (CAMH) Marijuana - Answers for Young People and Parents AD Addictions Addiction Research Foundation Addiction Research Foundation (ARF) Saying When: How to Quit Drinking or Cut Down AD Addictions Sanchez-Craig, Martha Addiction Research Foundation (ARF) 1993 Toward a New Life (For Reference Only) AD Addictions Bellwood Total Health Centre Bellwood Health Services Inc. -

Chef Michael Smith & Margaret Trudeau

FEATURING HEADLINERS Chef Michael Smith & Margaret Trudeau BEST-SELLING AUTHOR CBC HOST AND AUTHOR W.P. Kinsella Wab Kinew SUNday september 20, 2015 10:30 AM – 5:00 PM downtown saskatoon FREE ADMISSION 23rd St & 4th ave thewordonthestreet.ca in & around civic square FEATURING THE Saskatchewan Roughriders with Gainer CELEBRATing READING. ADVOCATING LITERACY Celebrating Reading. Advocating Literacy. PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Welcome to our 5th Annual Festival! On behalf of the Board of Directors, Executive Director, volunteers and sponsors, I’m delighted to celebrate The the best of Canadian writing and the importance of reading in our lives. A sincere thank you to all the sponsors and volunteers because without them we would not have a festival. Decision, decisions -- you have a lot of choices. This year's program includes power of exciting newcomers and legends of Canadian literature, our own local heroes as well as authors from across Canada. Check out the wide variety of exhibitors, enjoy the many activities for children, and visit with friends about literacy and reading. Be sure to visit the gourmet food trucks – and help us celebrate our 5th anniversary! Happy Reading, Graham Addley, President BOARD OF DIRECTORS Graham Addley, President Silvia Martini Words give us the unique ability VP, Interlink Research Inc. Anthony Bidulka, Vice President Author Vijay Kachru to teach, share and capture our Painter, Writer Jenica Nonnekes, Treasurer Senior Accountant, Virtus Group Lisa Vargo memories and knowledge. Department Head, Department of English, Yvette Nolan, Secretary University of Saskatchewan Playwright, Director Through words, we can learn from and be Caroline Walker Holly Borgerson Calder Inventory Manager, McNally Robinson Booksellers entertained by people that we have never met, On-line Bookseller, Graphic Artist in places that we have never been. -

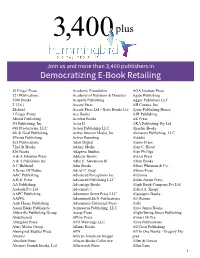

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,400 plus Join us and more than 3,400 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Academic Foundation AGA Institute Press 121 Publications Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Agate Publishing 1500 Books Acapella Publishing Aggor Publishers LLC 2.13.61 Accent Press AH Comics, Inc. 2dcloud Accent Press Ltd - Xcite Books Ltd Ajour Publishing House 3 Finger Prints Ace Books AJR Publishing 3dtotal Publishing Acrobat Books AK Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Actar D AKA Publishing Pty Ltd 498 Productions, LLC Action Publishing LLC Akashic Books 4th & Goal Publishing Active Interest Media, Inc. Akmaeon Publishing, LLC 5Points Publishing Active Parenting Aladdin 5x5 Publications Adair Digital Alamo Press 72nd St Books Adams Media Alan C. Hood 826 Books Adaptive Studios Alan Phillips A & A Johnston Press Addicus Books Alazar Press A & A Publishers Inc Adlai E. Stevenson III Alban Books A C Hubbard Adm Books Albert Whitman & Co. A Sense Of Nature Adriel C. Gray Albion Press A&C Publishing Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alchimia A.R.E. Press Advanced Publishing LLC Alden-Swain Press AA Publishing Advantage Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Adventure 1 Alfred A. Knopf AAPC Publishing Adventure Street Press LLC Algonquin Books AAPPL AdventureKEEN Publications Ali Warren Aark House Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Alibi Aaron Blake Publishers Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Alice James Books Abbeville Publishing Group Aesop Press Alight/Swing Street Publishing Abdelhamid Affirm Press Alinari 24 Ore Abingdon Press AFG Weavings LLC Alive Publications Abny Media Group Aflame Books All Clear Publishing Aboriginal Studies Press AFN All In One Books - Gregory Du- Abrams African American Images pree Absolute Press African Books Collective Allen & Unwin Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. -

Miscellaneous, Other & General Reading Author Publisher Place

Hard or Soft A B C D E F G H I J K L M S Miscellaneous, Other & General Reading Author Publisher Place Date ISBN Cover Comments M 1867: How the fathers made a deal MOORE, Christopher Christopher Moore Editorial Ltd. Toronto, ON 1998 0-7710-6096-3 S M 365 Days GLASSER, Ronald J. George Brazilier, Inc. New York, NY 1971 0-8076-0995-1 S M 50 popular beliefs that people think are true HARRISON, Guy Prometheus Books Amherst, NY 2012 978-1-61614-495-1 S also ISBN 13: 978-0-8160- FactsOnFile, Infobase 2007 H 6335-2, 2nd M A Brief History Of Canada RIENDEAU, Roger Publishing New York, NY 10: 0-8160-6335-4 edition M A Farewell to Arms HEMMINGWAY, Ernest Collier Macmillan Publishers New York, NY 1986 0-02-051900-1 S M A Few Good Men SUDDICK, Tom The Hearst Corporation New York, NY 1978 0-380-01866-7 S M A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius EGGERS, Dave Simon & Schuster New York, NY 2000 0-684-86347-2 H M A Midnight Clear WHARTON, William Ballantine Books New York, NY 1984 0-345-31291-0 S M A Nation Divided DOUGAN, Clark + LIPSMAN, Samuel Boston Publishing Company Boston, MA 1984 0-939526-11-5 H M A Piece of My Heart WALKER, Keith Ballantine Books New York, NY 1985 0-345-33997-5 S M A Tale of Two Cities DICKENS, Charles Wordsworth Classics 1859 9781853260391 S 1993 Printing M Acknowledgements: A Cultural Memoir and Other Essays KAY, Barbara Freedom Press Canada Inc.