UNLOCKING the INCLUSIVE GROWTH STORY of the 21ST CENTURY: ACCELERATING CLIMATE ACTION in URGENT TIMES Managing Partner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Urbanism: the Slow Evolution of a New Form

Informal Urbanism: The Slow Evolution of a New Form THE INFORMAL CITY One billion people live in slums worldwide.1 This accounts for a staggering one in six people globally, and the num- ber is climbing rapidly. The UN estimates that by 2030 it will be one in four people and by 2050 it will be one in three, for a total of three billion people.2 The vast major- ity of slum dwellers reported in the UN document are those living in the informal settlements of the developing world. Informal settlements vary in their characteristics, but what they have Dan Clark in common is a lack of adequate housing and even basic services such as University of Minnesota roads, clean water, and sanitation. In addition, residents often have no legal claim to the land they have built upon. Consequently, these neighborhoods develop outside the political and legal structure that defines the formal city. Existence outside these abstract organizational structures has a pro- found impact upon the spatial reality of these settlements. New construc- tion happens where and when it is needed, unconstrained by the principles of planning that regulate construction and guarantee integration of ser- vices elsewhere. In fact, the process at work in most informal settlements is a nearly perfect reversal of that at work in the formal city: buildings come first, and roads, utilities, and government follow later. How does this affect its form in comparison to the rest of the city? The building stock is normally shorter and less structurally robust. Its arrange- ment is often organic and more closely follows the terrain. -

2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors

THE WORLD BANK GROUP Public Disclosure Authorized 2016 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS Public Disclosure Authorized SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Public Disclosure Authorized Washington, D.C. October 7-9, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK GROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. Phone: (202) 473-1000 Fax: (202) 477-6391 Internet: www.worldbankgroup.org iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group (Bank), which consist of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), held jointly with the International Monetary Fund (Fund), took place on October 7, 2016 in Washington, D.C. The Honorable Mauricio Cárdenas, Governor of the Bank and Fund for Colombia, served as the Chairman. In Committee Meetings and the Plenary Session, a joint session with the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund, the Board considered and took action on reports and recommendations submitted by the Executive Directors, and on matters raised during the Meeting. These proceedings outline the work of the 70th Annual Meeting and the final decisions taken by the Board of Governors. They record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors and the resolutions and reports adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. In addition, the Development Committee discussed the Forward Look – A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030, and the Dynamic Formula – Report to Governors Annual Meetings 2016. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

LATIN AMERICAN CITIES DECLARATION on the COMPACT of MAYORS Acknowledging That Tack

C40 Chair: Mayor Eduardo Paes LATIN AMERICAN CITIES DECLARATION ON THE COMPACT OF Rio de Janeiro MAYORS C40 Board President: Michael R. Bloomberg Former Mayor of New York City Acknowledging that tackling climate change is vital to the long-term Addis Ababa health and prosperity of cities in Latin America, we, the undersigned Amsterdam Athens cities, are committing to taking action on climate change and publicly Austin Bangkok reporting on our progress. Barcelona Basel Beijing Berlin* We hereby declare our intent to comply with the Compact of Bogota Boston Mayors, the world’s largest cooperative effort among mayors and Buenos Aires* Cairo city leaders to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, prepare for the Cape Town Caracas impacts of climate change and track progress. Changwon Chicago Copenhagen* Curitiba The Compact of Mayors has defined a series of requirements that Dar es Salaam Delhi cities are expected to meet over time, recognizing that each city may Dhaka Hanoi be at a different stage of development on the pathway to compliance Heidelberg Ho Chi Minh City with the Compact. Hong Kong* Houston* Istanbul Jakarta* By signing this Declaration, we commit to advancing our city along Johannesburg* Karachi each stage of the Compact of Mayors, with the goal of becoming fully Lagos Lima compliant with all the requirements within three years. London* Los Angeles* Madrid Melbourne Specifically, the undersigned Mayors pledge to undertake the Mexico City Milan following for each of our cities: Moscow Mumbai • Develop and publicly report a greenhouse -

Regularización De Asentamientos Informales En América Latina

Informe sobre Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo • Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Regularización de asentamientos informales en América Latina E d é s i o F E r n a n d E s Regularización de asentamientos informales en América Latina Edésio Fernandes Serie de Informes sobre Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo El Lincoln Institute of Land Policy publica su serie de informes “Policy Focus Report” (Enfoque en Políticas de Suelo) con el objetivo de abordar aquellos temas candentes de política pública que están en relación con el uso del suelo, los mercados del suelo y la tributación sobre la propiedad. Cada uno de estos informes está diseñado con la intención de conectar la teoría con la práctica, combinando resultados de investigación, estudios de casos y contribuciones de académicos de diversas disciplinas, así como profesionales, funcionarios de gobierno locales y ciudadanos de diversas comunidades. Sobre este informe Este informe se propone examinar la preponderancia de asentamientos informales en América Latina y analizar los dos paradigmas fundamentales entre los programas de regularización que se han venido aplicando —con resultados diversos— para mejorar las condiciones de estos asentamientos. El primero, ejemplificado por Perú, se basa en la legalización estricta de la tenencia por medio de la titulación. El segundo, que posee un enfoque mucho más amplio de regularización, es el adoptado por Brasil, el cual combina la titulación legal con la mejora de los servicios públicos, la creación de empleo y las estructuras para el apoyo comunitario. En la elaboración de este informe, el autor adopta un enfoque sociolegal para realizar este análisis en el que se pone de manifiesto que, si bien las prácticas locales varían enormemente, la mayoría de los asentamientos informales en América Latina transgrede el orden legal vigente referido al suelo en cuanto a uso, planeación, registro, edificación y tributación y, por lo tanto, plantea problemas fundamentales de legalidad. -

Constructing Citizenship and Gender from Below

Bea Wittger Squatting in Rio de Janeiro Urban Studies To my mother Bea Wittger completed her doctorate in Latin American History from the Univer- sity of Cologne. Her research interests include Gender, Intersectionality, Citizen- ship, Social Movements, Urban History, with special focus on Brazil. Bea Wittger Squatting in Rio de Janeiro Constructing Citizenship and Gender from Below This study was accepted as a doctoral dissertation by the Faculty of Arts and Hu- manities of the University of Cologne and has been kindly supported by the Fede- ral Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the Research Network for Latin America Ethnicity, Citizenship, Belonging. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of li- braries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative desig- ned to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3547-2. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National- bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeri- vatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial pur- poses, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@transcript- publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

PROGRAMME What Way Forward for the EU27 and Eurozone?

The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 organised in association with the Estonian EU Council Presidency TALLINN I 13, 14 & 15 SEPTEMBER PROGRAMME What way forward for the EU27 and Eurozone? LEAD SPONSORS SUPPORT SPONSORS The Eurofi Tallinn Forum mobile website tallinn2017.eurofi.net The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 Answer polls TALLINN │ 13, 14 & 15 September Post questions during the sessions Check-out the list of speakers and contact attendees Detailed programme and logistics information PROGRAMME TO ACCESS THE TALLINN FORUM MOBILE WEBSITE • Click on the link contained in the SMS you received after registration • Direct access : tallinn2017.eurofi.net • QR code The Eurofi Tallinn Forum mobile website tallinn2017.eurofi.net The Eurofi Financial Forum 2017 Answer polls TALLINN │ 13, 14 & 15 September Post questions during the sessions Check-out the list of speakers and contact attendees Detailed programme and logistics information PROGRAMME DAY 1 I 13 SEPTEMBER AFTERNOON MACRO-ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL CHALLENGES Estonia Room Tallinn Room 12:30 to 13:30 WELCOME LUNCH Foyer 13:30 to 14:00 Opening remarks: Governor A. Hansson Speech: Kara M. Stein p.8 14:00 to 14:30 Exchange of views: C. Clausen, M. Pradhan & D. Wright Outlook for the EU27 economy p.10 14:30 to 15:35 14:30 to 15:35 Sustainable finance: Improving financing prospects for EU EU and emerging market challenges infrastructure projects and mid-sized enterprises p.12 p.14 15:35 to 16:40 15:35 to 16:40 Accelerating the resolution of NPL challenges Challenges raised by green finance and FSB disclosure guidelines p.16 p.18 COFFEE BREAK Foyer 16:55 to 18:00 16:55 to 18:00 Developing Baltic / Eastern European Longevity and ageing: Opportunities capital markets in the context of the CMU and challenges associated with the PEPP p.20 p.22 18:00 to 19:20 The economic, financial stability and trade implications of Brexit p.24 19:20 to 20:15 Exchange of views: C. -

U20 Rome-Milan 2021 – Urban 20 Calls on G20 To

TRADUZIONE ITALIANA DI CORTESIA Guidati dalle città co-presidenti di Roma e Milano, noi, i sindaci e governatori delle città sottoscritte, riuniti come Urban 20 (U20), invitiamo i Leader del G20 a collaborare con le città per realizzare società incentrate sull’uomo, eque, a emissioni zero, a prova di cambiamenti climatici, inclusive e prospere. La natura trasformativa dell'Agenda 2030 offre alle città un'opportunità chiave per promuovere un nuovo paradigma di sviluppo sostenibile e avviarsi verso una ripresa resiliente dalla crisi umanitaria causata dal COVID-19. Sindaci e governatori sono in prima linea nella risposta alla pandemia da COVID-19 e all'emergenza climatica. Il modo in cui i leader indirizzeranno i finanziamenti per la ripresa da COVID-19 rappresenta la sfida più significativa per qualsiasi governo impegnato nella risposta a pandemia ed emergenza climatica. La pandemia da COVID-19 ha messo in luce la solidarietà tra città e ha sottolineato l'importanza di lavorare insieme a soluzioni locali che garantiscano che nessuno e nessun luogo vengano dimenticati. Ha sottolineato che istituzioni pubbliche forti e la fornitura di servizi sono vitali per la coesione delle nostre comunità e per garantire l'accesso universale all'assistenza sanitaria in maniera equa per tutti. Per garantire che la fornitura di servizi pubblici a livello locale venga mantenuta, che le persone siano protette e che si realizzi una ripresa verde, giusta e sostenibile dalla pandemia da COVID- 19, le città devono avere accesso diretto a forniture e finanziamenti da fonti internazionali e nazionali, per esempio dai recovery plan nazionali. L'accesso equo ai vaccini deve essere garantito a tutti, in particolare alle città dei paesi in via di sviluppo. -

Rapid Desk Based Study

RAPID DESK BASED STUDY: Evidence and Gaps in Evidence on the Principle Political Economy Constraints and Opportunities to Successful Investment in Clean Energy in Asia Duke Ghosh and Anupa Ghosh January 2016 This report has been produced by Global Change Research, Kolkata and Department for Economics, The Bhawanipur Education Society College, Kolkata for Evidence on Demand with the assistance of the UK Department for International Development (DFID) contracted through the Climate, Environment, Infrastructure and Livelihoods Professional Evidence and Applied Knowledge Services (CEIL PEAKS) programme, jointly managed by DAI (which incorporates HTSPE Limited) and IMC Worldwide Limited. The views expressed in the report are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily represent DFID’s own views or policies, or those of Evidence on Demand. Comments and discussion on items related to content and opinion should be addressed to the author, via [email protected] Your feedback helps us ensure the quality and usefulness of all knowledge products. Please email [email protected] and let us know whether or not you have found this material useful; in what ways it has helped build your knowledge base and informed your work; or how it could be improved. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12774/eod_hd.january2016.ghoshdetal First published January 2016 © CROWN COPYRIGHT Contents Report Summary ........................................................................................................ iii SECTION 1............................................................................................... -

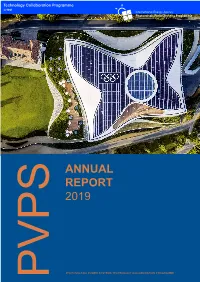

Iea Pvps Annual Report 2019 Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme

Cover photo THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE’S (IOC) NEW HEADQUARTERS’ PV ROOFTOP, BUILT BY SOLSTIS, LAUSANNE SWITZERLAND One of the most sustainable buildings in the world, featuring a PV rooftop system built by Solstis, Lausanne, Switzerland. At the time of its certification in June 2019, the new IOC Headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, received the highest rating of any of the LEED v4-certified new construction project. This was only possible thanks to the PV system consisting of 614 mono-Si modules, amounting to 179 kWp and covering 999 m2 of the roof’s surface. The approximately 200 MWh solar power generated per year are used in-house for heat pumps, HVAC systems, lighting and general building operations. Photo: Solstis © IOC/Adam Mork COLOPHON Cover Photograph Solstis © IOC/Adam Mork Task Status Reports PVPS Operating Agents National Status Reports PVPS Executive Committee Members and Task 1 Experts Editor Mary Jo Brunisholz Layout Autrement dit Background Pages Normaset Puro blanc naturel Type set in Colaborate ISBN 978-3-906042-95-4 3 / IEA PVPS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 PHOTOVOLTAIC POWER SYSTEMS PROGRAMME PHOTOVOLTAIC POWER SYSTEMS PROGRAMME ANNUAL REPORT 2019 4 / IEA PVPS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE A warm welcome to the 2019 annual report of the International Energy Agency Photovoltaic Power Systems Technology Collaboration Programme, the IEA PVPS TCP! We are pleased to provide you with highlights and the latest results from our global collaborative work, as well as relevant developments in PV research and technology, applications and markets in our growing number of member countries and organizations worldwide. -

World News Agencies and Their Countries

World News Agencies and their Countries World News Agencies and their Countries Here, you will read about the World News Agencies and their Countries World News Agencies and their Countries 1. Bakhtar News Agency is located in which Country? – Afghanistan 2. Where is the Xinhua (New China News Agency) located? – China 3. Agencia de Noticias Fides (ANF) is the News agency located in which Country? – Bolivia 4. Albanian Telegraphic Agency (ATA) is located in which Country? – Albania 5. Where is the Cuban News Agency (ACN) located? – Cuba 6. Angola Press (Angop) is located in which Country? – Angola 7. Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) located in which Country? – Iran 8. Telam is the News agency located in which Country? – Argentina 9. Novinite is the News agency located in which Country? – Bulgaria 10. Armenpress is the News agency located in which Country? – Armenia 11. Agencia Estado is the News agency located in which Country? – Brazil 12. Where is the Agence Djiboutienne d’Information News Agency located? – Djibouti 13. Oe24 News is the News website located in which Country? – Austria 14. Azartac is the News agency located in which Country? – Azerbaijan 15. Mediapool is the News agency located in which Country? – Bulgaria 16. Where is the Agencia Globo Press Agency located? – Brazil 17. Where is the Bahrain News Agency (BNA) located? – Bahrain 18. Where is the Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) News Agency (BNA) located? – Bangladesh 19. Where is the Belta News Agency (BNA) located? – Belarus 20. Where is the Walta Information Centre (WIC) News Agency located? – Ethiopia 21. Where is the Belga Press Agency located? – Belgium 22. -

Agricultural Trade & Policy Responses During the First Wave of the COVID

AGRICULTURAL TRADE & POLICY RESPONSES DURING THE FIRST WAVE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC IN 2020 AGRICULTURAL TRADE & POLICY RESPONSES DURING THE FIRST WAVE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC IN 2020 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 Required citation: FAO. 2021. Agricultural trade & policy responses during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN 978-92-5-134366-1 © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted.