D B R Ambedkar Memorial Lect Ur E 2015 Is Unbridled Capitalism A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Another Side of India: Gender, Culture and Development

Another Side of India: Gender, Culture and Development Brenda Gael McSweeney, Editor Foreword by Gita Sen General Editing by Mieke Windecker with Margaret Hartley The ideas and opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of UNESCO. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO or the authors concerning the legal status of any country, city or area of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. Cover painting credit: © Anuradha Dey (Shantiniketan, West Bengal, India) Published in 2008 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, Place de Fontenoy, 75352 PARIS 07 SP Copyright ©Dr. Brenda Gael McSweeney All rights reserved. No part of this document including photographs can be reproduced in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission of Dr. Brenda Gael McSweeney. i Contents Foreword iv Gita Sen Preface: Origins and Acknowledgements v Brenda Gael McSweeney Contributors vii Introduction xii Krishno Dey Part One Governance and Political Voice 1. Engendering Panchayats 2 Niraja Gopal Jayal 2. She’s in Charge Now: An Examination of Women’s Leadership in the Panchayati Raj Institutions in Karnataka 8 Shiwali Patel 3. Public Space and Women’s Rights: Fine Tuning Democracy 30 Kumkum Bhattacharya Part Two Livelihoods and Education 4. Srihaswani: a Gender Case Study 39 Krishno Dey, Chandana Dey and Brenda Gael McSweeney with Rajashree Ghosh 5. -

Entrance Examination 2020 Ma Communication Media Studies

r ENTRANCE EXAMINATION 2020 Code: W-39 MA COMMUNICATION MEDIA STUDIES MAXIMUM MARKS: 60 DURATION: TWO HOURS IHALL TICKET NUMBER I READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE PROCEEDING: • Enter your hall ticket number on the question paper & the OMR sheet without fail • Please read the instructions for each section carefully • Read the instructions on the OMR sheet carefully before proceeding • Answer all questions in the OMR sheet only • Please return the filled in OMR sheet to the invigilator • You may keep the question paper with you • All questions carry equal negative marks. 0.33 marks will be subtracted for every wrong answer • No additional sheets will be provided. Any rough work may be done in the question paper itself TOTAL NUMBER OF PAGES EXCLUDING THIS PAGE: 09 (NINE) r I. GENERAL & MEDIA AWARENESS (lX30=30 MARKS) Enter the correct answer in the OMR sheet 1. Which video conferencing platfotm was found to be leaking personal data to strangers amid the CDVJD-19 crisis? A) Blue Jeans B) Zoom C) Youtube D)GoogleMeet 2. Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh, which has been in the news over the past two years, A) Is a garment district B) Shipbreaking yard C) Has a Rohingya refugee camp D) Beachside tourist spot 3. Satya Nadella is to Microsoft a5_____ is to IBM. A) Sundar Pichai B) Arvind Krishna C) Shantanu Narayan D) Nikesh A 4. Legacy Media is a term used to describe -----=:-:-:c-cc-:-. A) Family run media companies B)Media forms that no longer exist C) Print & broadcast media D) Government-owned media S. The Asian Games 2022 will be held in _____. -

CJP Ayodhya Petition

1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION I.A NO. _______ OF 2017 IN CIVIL APPEAL NO. 10866 -10867 OF 2010 IN THE MATTER OF: Mohammad Siddiq@ Hafiz Mohammad Siddiq Etc. etc Appellants Versus Mahant Suresh Dase & Ors. Etc Respondents Etc . AND IN THE MATTER OF: 1. Shyam Benegal, 103, Sangam, Pedder Road, B/h Jaslok Hospital, Mumbai – 400026 Applicant No. 1 2. Aparna Sen, Block 10, Apt 14 A&B, Bengal Silver Spring, 5 JBS Haldane Avenue EM Bypass, Kolkata 700 105 Applicant No.2 3. Anil Dharker, 15-B, Harmony Tower, Opp. Toyota Showroom, Worli, Dr. Moses Road, Acharya Chowk, Mumbai - 400018 Applicant No.3 4. Teesta Setalvad Nirant, Juhu Tara Road, Juhu, Mumbai – 400049 Applicant No. 4 5. Om Thanvi, A-304 Jansatta Apts, Sector 9, Vasundhara, Ghaziabad – 201012. UP Applicant No.5 6. Cyrus J. Guzder AFL Pvt. Ltd., AFL House, Lok Bharati Complex, Marol-Maroshi Road, Andheri (East), Mumbai – 400059 Applicant No.6 7. Aruna Roy, Village Tilonia, Ajmer District, Kishangarh, Rajasthan-305816 Applicant No.7 2 8. Ganesh N. Devy 188, II Main, I Cross, Narayanpur, DHARWAD 580 008, Applicant No.8 9. Dr. B.T. Lalitha Naik #22, 1st Main, 2nd Cross, Judicial Officer's Colony, Sanjaynagar, RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560094 Applicant No.9 10. Medha Patkar 6/6, Jangpura B, New Delhi - 110014 Applicant No.10 11. Kumar Ketkar, 29/6, Hundiwala Apartment, Ground Floor, Opp. Apollo Pharmacy, Kopri, Thane (East), Thane – 400603 Applicant No.11 12. Anand Patwardhan 27 Lokmanya Tilak Colony Marg, 2nd Floor, Street No. -

Transparency Review

Volume II, No. 6 December, 2009 Transparency Review Journal of Transparency Studies MORTAL THREAT TO MEDIA he practice of newspapers accepting in campaigning to arouse awareness of the money to portray advertisements as mounting danger to the media. He Tnews is not new. Major dailies and circulated examples of tainted coverage and journals have yielded to the temptation of the rate cards put out by leading Hindi publishing ‘advertorials’ by failing to mark newspapers for publishing favourable clearly that a column or supplement has handouts and pictures of particular been paid for. This may candidates. He took his help the advertiser to complaint to the promote his case by Chairman of the Press borrowing the cloak of Council. credibility, but does P. Sainath’s grave damages to the exhaustive investigation credibility of the media. in The Hindu of When the practice is promotional coverage in taken to the extent of Maharashtra favouring charging huge sums to the candidature of the promote the prospects of Chief Minister shows particular election how deep the disease candidates, the injury goes. Veteran journalist becomes life-threatening. Inder Malhotra places It strikes at the vitals of the threat in perspective. the democratic process A wide-ranging survey that the media is sworn to of the business interests uphold; it suggests that influencing media its life-blood of control and priorities is credibility is up for sale. provided by N. Bhaskar Fortunately, the main Rao, Chairman of the news inputs of the papers we read every Centre for Media Studies (CMS). morning seem untainted, but the death of Our previous issue focussed on the credible news looms unless effective Bhilwara achievement. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

Annual Report 2013-2014 Annual Report 2013 - 2014

okf”kZd izfrosnu 2013-2014 Annual Report 2013-2014 Annual Report 2013 - 2014 CENTRE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Dharma Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi 110021 (INDIA) VISION STATEMENT * VISION To be a leader among the influential national and international think tanks engaged in the activities of undertaking public policy research and education for moulding public opinion. * OBJECTIVES The main objectives of the Centre for Policy Research are: 1. to promote and conduct research in matters pertaining to a) developing substantive policy options; b) building appropriate theoretical frameworks to guide policy; c) forecasting future scenarios through rigorous policy analyses; d) building a knowledge base in all the disciplines relevant to policy formulation; 2. to plan, promote and provide for education and training in policy planning and management areas, and to organise and facilitate Conferences, Seminars, Study Courses, Lectures and similar activi- ties for the purpose; 3. to provide advisory services to Government, public bodies, private sector or any other institutions including international agencies on matters having a bearing on performance, optimum use of national resources for social and economic betterment; 4. to disseminate information on policy issues and knowhow on policy making and related areas by undertaking and providing for the publication of journals, reports, pamphlets and other literature and research papers and books; 5. to engage the public sphere in policy debates; produce policy briefs to liaise with legislatures; and 6. to create a community of researchers. * LIST OF ACTIVITIES/SUBJECTS PURSUED 1. Political Issues and Governance; 2. International Relations and Foreign Policy/Diplomacy; 3. Economic Policy Issues, National, Bilateral, Regional, and Global; 4. -

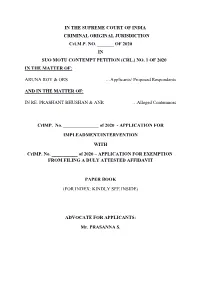

Of 2020 in Suo Motu Contempt Petition (Crl.) No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION Crl.M.P. NO. _______ OF 2020 IN SUO MOTU CONTEMPT PETITION (CRL.) NO. 1 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: ARUNA ROY & ORS …Applicants/ Proposed Respondents AND IN THE MATTER OF: IN RE. PRASHANT BHUSHAN & ANR …Alleged Contemnors CrlMP. No. _______________ of 2020 - APPLICATION FOR IMPLEADMENT/INTERVENTION WITH CrlMP. No. ___________ of 2020 – APPLICATION FOR EXEMPTION FROM FILING A DULY ATTESTED AFFIDAVIT PAPER BOOK (FOR INDEX: KINDLY SEE INSIDE) ADVOCATE FOR APPLICANTS: Mr. PRASANNA S. S.No Particulars Page Nos. 1. I.A. No. _____ of 2020 1 - 29 Application for Impleadment/Intervention along with Affidavit 2. ANNEXURE-A-1 30 -31 The order of this Hon’ble Court dated 22.07.2020, issuing notice on the Suo Motu Contempt proceedings to the Attorney General for India and to the Alleged Contemnor Mr. Prashant Bhushan 3. ANNEXURE-A-2 32 - 33 A true copy of the tweet dated 28.06.2020 by twitter handle @SaketGokhale 4. ANNEXURE-A-3 34 - 37 A true copy of the Statement dt. 27.07.2020 5. ANNEXURE-A-4 38 - 41 A true copy of the article dated 30.07.2020 as it appeared on barandbench.com 6. ANNEXURE-A-5 42 - 46 A true copy of the article dated 27.07.2020 published in The Hindu written by Justice A.P. Shah, former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court 7. ANNEXURE-A-6 A true copy of the article dated 27.07.2020 published in The 47 – 51 Hindu written by Mr. -

E81 Aruna Roy Mixdown

Brown University Watson Institute | E81_Aruna Roy_mixdown [MUSIC PLAYING] SARAH BALDWIN:From the Watson Institute at Brown University, this is Trending Globally. I'm Sarah Baldwin. Aruna Roy is one of India's most prominent activists. In 1968, she became a civil servant in the Indian Administration Service. But in 1975, she left her role in government and started working directly with poor and marginalized communities. Because as she sees it, social justice work isn't driven by government officials. ARUNA ROY: The real change starts with the specifics. One has to get absolutely to the root of an issue. And it is from there the real change occurs. SARAH BALDWIN:In 1987, Roy and two other activists founded MKSS, the Association for the Empowerment of Laborers and Farmers. They've fought for everything from the right to work, to food security, to government transparency. Roy is currently a fellow at the Watson Institute. Her new book, Power to the People-- The Right To Information Story, looks at how this fight for government transparency in India grew from a movement into a law. We started by talking about her time in India's civil service, before she began her work as an activist. ARUNA ROY: I was trained for two years. It's very rigorous training. And you're taught what I call, government management. Business management is about how to run a business and make profit. The civil service teaches you-- the training in civil service-- makes you managers. Management of welfare state, of delivering services to the poor, ensuring that constitutional values are realized. -

“Right to Information: the Road Ahead”

National Convention on “Right to Information: The Road Ahead” Organised by Media Information and Communication Centre of India (MICCI) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES), In collaboration with The International Centre, Goa (ICG) SPEAKERS’ PROFILE Anshika Mishra, Senior Correspondent, DNA – Mumbai. Prof. Abdur Rahim is one of the senior-most journalism and mass communication educationists in India. Having retired from India’s prestigious journalism school at Osmania University, Hyderabad after 35 years of service as Chairman and Dean, he is presently serving as Visiting Professor at the Moulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. He is a Visiting Faculty for many Journalism and Mass Communication Departments all over the country. Widely traveled, he has lectured at the famous Columbia School of Journalism, at Harvard School of Government and Oxford University. He has participated in many international media conferences and addressed Seminars. An author of several books on media, he has contributed hundreds of articles in research journals, newspapers, both in India and abroad, and magazines. His areas of specialization are media theory and research, media ethics, and development communication. He is presently the Vice-President of the Commonwealth Association for Education in Communication and Journalism (CAEJAC) and the Secretary of the South Asian Media Association (SAMA) and Chairman of Bharat Samachar. He is also Chapter Head of MICCI (Andhra Pradesh). Email - [email protected] Dr. I. Arul Aram , PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Media Sciences, Anna University, Chennai, India. He is formerly a Chief Sub-Editor with The Hindu newspaper. He had also served as the President of the Madras Press Club. -

UNPACKING PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY from Theory to Practice and from Practice to Theory

A REPORT ON TWO WORKSHOPS Montreal • Thiruvananthapuram UNPACKING PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY From theory to practice and from practice to theory 1 Acknowledgements Part A. Unpacking Participatory Democracy: An Overview I. Unpacking Participatory Democracy: A Review II. Culture and Democracy Part B. Detailed Reports of the two Workshops III. Unpacking Participatory Democracy From Theory To Practice: The Montreal Workshop (November 2016) • Executive Summary • Details of Workshop Discussions IV. Unpacking Participatory Democracy From Practice to Theory: The Thiruvananthapuram Workshop (30 Jan 2017 - 1 Feb 2017) • Executive Summary • Details of Workshop Discussions CONTENTS 2 3 Acknowledgements he two workshops would not have been We are also grateful to the Chief Minister and This document rests on the excellent possible without the financial support of Chief Secretary of the Government of Kerala, summaries and reports of Moyukh Tthe Erin Jellel Collins Arsenault Trust. the Institute of Management and Governance Chatterji and Suchi Pande of the Montreal (IMG) Thiruvananthapuram and the Tata and Thiruvananthapuram workshops. I want to acknowledge the generous support Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai S. Anandalakshmy, Siddhartha and Nikhil Dey of time and help from Sonia Laszlo, Iain Blair for support in Thiruvanathapuram, Kerala. We helped with putting all the writing together. and Sheryl Ramsahai at the ISID, McGill would like to thank IMG for their affectionate Vinay Jain did the designing of the report and University and McGill Centre for Human hospitality and Dr. Parasuraman & TISS for the booklets, McGill, Anurag Singh and Taru Rights and Legal Pluralism. The efficient the offer to help with emergencies. A heartfelt for the photos. -

Nobel Prize - 2015

Nobel prize - 2015 ★ Physics - Takaaki Kajita, Arthur B. Mcdonald ★Chemistry - Tomas Lindahl, Paul L. Modrich, Aziz Sanskar ★Physiology or Medicine - William C. Campbell, Satoshi Omura, Tu Youyou ★Literature - Svetlana Alexievich (Belarus) ★Peace - Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet ★Economics - Angus Deaton Nobel prize - 2016 ★Physics - David J. Thouless, F. Duncan M. Haldane, J. Michael Kosterlitz ★Chemistry - Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J.Fraser Stoddart, Bernard L. Feringa ★Physiology or Medicine - Yoshinori Ohsumi ★Literature - Bob Dylan ★Peace - Juan Manuel Santos ★Economics - Oliver Hart, Bengt Holmstrom Nobel prize - History Year Honourable Subject Origin 1902 Ronald Ross Medicine Foreign citizen born in India 1907 Rudyard Kipling Literature Foreign citizen born in India 1913 Rabindranath Literature Citizen of India Tagore 1930 C.V. Raman Physics Citizen of India 1968 Har Gobind Medicine Foreign Citizen of Indian Khorana Origin 1979 Mother Teresa Peace Acquired Indian Citizenship 1983 Subrahmanyan Physics Indian-born American Chandrasekhar citizen 1998 Amartya Sen Economi Citizen of India c Sciences 2009 Venkatraman Chemistr Indian born American Ramakrishna y Citizen Booker Prize Year Author Title 2002 Yann Martel Life of Pi 2003 DBC Pierre Vernon God Little 2006 Kiran Desai The Inheritance of Loss 2008 Aravind Adiga The White Tiger 2009 Hilary Mantel Wolf hall 2010 Howard Jacobson The Finkler Question 2011 Julian Barnes The Sense of an Ending 2012 Hilary Mantel Bring Up the Bodies 2013 Eleanor Catton The Luminaries 2014 Richard Flanagan The Narrow Road to the Deep North 2015 Marlon James A Brief History of Seven Killings 2016 Han Kang, Deborah Smith The Vegetarian Booker Prize - Facts ★In 1993 on 25th anniversary it was decided to choose a Booker of Bookers Prize and the decision was done by a panel of three judges. -

The Dr. Deepa Martins Memorial Lectures Volume One: 2004 - 2009 Ms

Deepalaya The Dr. Deepa Martins Memorial Lectures Volume One: 2004 - 2009 Ms. Mrinal Pande Shri Ved Vyas 2004 2004 Ms. Aruna Roy Dr. C.S. Lakshmi 2005 2005 - 1 - Deepalaya The Dr. Deepa Martins Memorial Lectures Volume One: 2004 - 2009 The lamps are different, But the Light is the same. - Rumi - 2 - - 3 - AN INTRODUCTION TO DR. DEEPA MARTINS AND THE MEMORIAL LECTURES It is not easy to give a glimpse of the life and work of Dr. Deepa Martins in a few words, yet there are five words that are metaphoric to her multi-dimensional and complete personality, and these five words were also very close to her heart and the work she did – dedication harmony, integration, compassion, communication. bUgha ik¡p “kCnksa esa ls ,d “kCn dks mUgksaus vius fuokl ds uke ds fy, pqukA os ik¡p “kCn gSa & leiZ.k] leUo;] lef"V] laosnuk vkSj laoknA leiZ.k dk Hkko muds laiw.kZ thou esa mtkxj jgk gSA 5 vizSy 1951 dks] vtesj esa ,d dqekÅ¡uh czkg~e.k ifjokj esa MkW- nhik ekfVZUl dk tUe gqvkA lkr Hkkb;ksa vkSj rhu cguksa esa lcls NksVh MkW- nhik ds vk/;kfRed rFkk pkfjf=d fodkl esa muds v/;kid firk Jh Hkxoku oYyHk iar dk laiw.kZ ;ksxnku jgkA muds ckÅth dh mnkjrk rFkk mudh Ãtk dh lknxh o dRrZO;c)rk ls gh muds O;fDrRo dh uhao dh jpuk gqbZA f”k{kk o fodkl dks lefiZr MkW- nhik izkjaHk ls gh izfrHkk”kkyh jghaA os u flQZ i<+kbZ oju~ vU; “kSf{kd o lg&”kSf{kd xfrfof/k;ksa tSls fd okn&fookn] ys[ku] vfHku; vkfn esa viuh izfrHkk fu[kkjrh jghaA flQZ vius gh ugha oju~ lcds laiw.kZ fodkl dh vksj lefiZr MkW- nhik vius ifjokj rFkk fe=ksa dks Hkh ges”kk izsj.kk nsrh jghaA lkfo=h Ldwy ls mUgksaus lSd.Mjh o baVjehfM;sV dj lkfo=h dkWyst ls ch-,- fd;kA viuh usr`Ro {kerk dk izn”kZu djrs gq,] os vius dkWyst dh Copyright: St.