Pilgrim's Progress a New Look at an Ancient Path of Pilgrimage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Parks and Iccas in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, June 11, 2013, IP: 129.79.203.216] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 11(1): 29-45, 2013 Special Section: Article National Parks and ICCAs in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities Stan Stevens Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In Nepal, as in many states worldwide, national parks and other protected areas have often been established in the customary territories of indigenous peoples by superimposing state-declared and governed protected areas on pre-existing systems of land use and management which are now internationally considered to be Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs, also referred to Community Conserved Areas, CCAs). State intervention often ignores or suppresses ICCAs, inadvertently or deliberately undermining and destroying them along with other aspects of indigenous peoples’ cultures, livelihoods, self-governance, and self-determination. Nepal’s high Himalayan national parks, however, provide examples of how some indigenous peoples such as the Sharwa (Sherpa) of Sagarmatha (Mount Everest/Chomolungma) National Park (SNP) have continued to maintain customary ICCAs and even to develop new ones despite lack of state recognition, respect, and coordination. The survival of these ICCAs offers Nepal an opportunity to reform existing laws, policies, and practices, both to honour UN-recognised human and indigenous rights that support ICCAs and to meet International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) standards and guidelines for ICCA recognition and for the governance and management of protected areas established in indigenous peoples’ territories. -

The Sherpa and the Snowman

THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN Charles Stonor the "Snowman" exist an ape DOESlike creature dwelling in the unexplored fastnesses of the Himalayas or is he only a myth ? Here the author describes a quest which began in the foothills of Nepal and led to the lower slopes of Everest. After five months of wandering in the vast alpine stretches on the roof of the world he and his companions had to return without any demon strative proof, but with enough indirect evidence to convince them that the jeti is no myth and that one day he will be found to be of a a very remarkable man-like ape type thought to have died out thousands of years before the dawn of history. " Apart from the search for the snowman," the narrative investigates every aspect of life in this the highest habitable region of the earth's surface, the flora and fauna of the little-known alpine zone below the snow line, the unexpected birds and beasts to be met with in the Great Himalayan Range, the little Buddhist communities perched high up among the crags, and above all the Sherpas themselves that stalwart people chiefly known to us so far for their gallant assistance in climbing expeditions their yak-herding, their happy family life, and the wav they cope with the bleak austerity of their lot. The book is lavishly illustrated with the author's own photographs. THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN "When the first signs of spring appear the Sherpas move out to their grazing grounds, camping for the night among the rocks THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN By CHARLES STONOR With a Foreword by BRIGADIER SIR JOHN HUNT, C.B.E., D.S.O. -

Sl.No Name of Religious and Cultural Sites

Travelling guide to religious and cultural sites in Bumthang Dzongkhag Gewog : Choekhor Sl.No Name of religious and cultural sites Description of sites Nearest road Distance from Distance to Contact person Contact Remarks point Chamkhar town the site number from the 1 Tashi Gatshel Dungtsho Lhakhang The main nangten of the Lhakhang are statues of Lusibi 20 Km 5 Mins Walk Tashi Tshering, 17699859 Guru Nangsi , Tempa, Chana Dorji. Caretaker 2 Sanga Choling Lhakhang The main relice of the Lhakhang is Guru Tshengye statuDhur toe 20 Km 5 Mins Walk Kezang Dorji, 17778709 Caretaker 3 Dhurm Mey Dungkhor Lhakhang The main nangten of the lhakhang are painiting of Dhurmey 19 Km 15 Mins Yeshi Pema, 17554125 Guru Rinpoche and Tshepamey. Caretaker 4 Dhur Dungkhor Lhakhang The main relices of lhakhang are statues of Chenrizey Dhurmey 19 Km 10 mins Ngawang 17577992 and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal. walk 5 Dhendup Choling Lhakhang The main relices of Lhakhang are Desum Sangay and Dhurmey 19 Km 15 mins Lam Kinley 17603534 Guru Sangay 6 Barsel Lamsel/Dawathang Lhakhang The main relices of Lhakhang is Statues of Guru Dawathang 7 Km 1 min walk Kezang Dawa, Car 77661214 Rinpoche and a small, grey image of Thangtong Gyalpo. 7 Lhamoi Nyekhang The main relice of the Lhakhang is Guru Tshengye statuDawathang 7.5 Km 10 mins Choney Dorji, Lam 17668141 walk 8 Kurjey Guru Lhakang Status of Guru Rimpoche and Guru mediated in one Kurjey 7 Km 1 min walk Kinley, Caretaker 77113811 caves and left body imprint. 9 Kurjey Sampalhendup Lhakhang The main nangten is status of Guru Rinpoche. -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

Tibet: Psychology of Happiness and Well-Being

Psychology 410 Psychology of Well-Being and Happiness Syllabus: Psychology 410, Summer 2020 Psychology of Happiness and Well-Being Course Content: The goal of this course is to understand and experience teachings on happiness and well-being that come from psychological science and from Buddhism (particularly Tibetan Buddhism), through an intercultural learning experience in Tibet. Through being immersed in authentic Tibetan community and culture, students will be able to have an anchored learning experience of the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism and compare this with their studies about the psychological science of well-being and happiness. Belief in Buddhism or any other religion is not necessary for the course. The cultural experiences in Tibet and understanding the teachings of Buddhism give one assemblage point upon which to compare and contrast multiple views of happiness and well-being. Particular attention is given in this course to understanding the concept of anxiety management from a psychological science and Buddhist viewpoint, as the management of anxiety has a very strong effect on well- being. Textbook (Required Readings): The course uses open source readings and videos that can be accessed through the PSU Library proxies, and open source websites. Instructors and Program Support Course Instructors and Program Support: Christopher Allen, Ph.D. and Norzom Lala, MSW candidate. Christopher and Norzom are married partners. ChristopherPsyc is an adjunct faculty member and senior instructor in the department of psychology at PSU. He has won the John Eliot Alan award for outstanding teacher at PSU in 2015 and 2019. His area of expertise includes personality and well- being psychology, and a special interest in mindfulness practices. -

High Peaks, Pure Earth

BOOK REVIEW HIGH PEAKS, PURE EARTH COLLECTED WRITINGS ON TIBETAN HISTORY AND CULTURE BY HUGH RICHARDSON A COMPILATION OF A SERIES OF PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 HIGH PEAKS, PURE EARTH High Peaks, Pure Earth is the title of the collected works on Tibetan history and culture by Hugh Richardson, a British diplomat who became a historian of Tibet. He was British representative in Lhasa from 1936 to 1940 and again from 1946 to 1950, during which time he did many studies on ancient and modern Tibetan history. He wrote numerous articles on Tibetan history and culture, all of which have been published in this book of his collected writings. Hugh Richardson was born in Scotland, a part of Great Britain that bears some similarities to Tibet, both in its environment and in its politics. Scotland has long had a contentious relationship with England and was incorporated only by force into Great Britain. Richardson became a member of the British administration of India in 1932. He was a member of a 1936 British mission to Tibet. Richardson remained in Lhasa to become the first officer in charge of the British Mission in Lhasa. He was in Lhasa from 1936 to 1940, when the Second World War began. After the war he again represented the British Government in Lhasa from 1946 to 1947, when India became independent, after which he was the representative of the Government of India. He left Tibet only in September 1950, shortly before the Chinese invasion. Richardson lived in Tibet for a total of eight years. -

Meditation on Love and Compassion by Shamar Rinpoche

THE PATH Dedicated to the Realization of Wisdom and Compassion Bodhi Path Buddhist Centers Summer 2011 Meditation on Love and Compassion by Shamar Rinpoche In general when we practice the Dharma and we commit ourselves to accomplishing positive actions, we encounter obstacles and difficulties. This is due to the fact that our minds are laden with emotions. Of these negative emotions, the main one is pride, which leads us to feel contempt for others (due to an over- estimation of oneself: I am the best, the strongest, etc). The existence of pride automatically gives rise to jealousy, hatred, or anger. With pride as its underly- ing cause, the emotion of anger creates the most pow- erful effects. This is because it leads us to carry out all kinds of seriously negative actions that will bring about future rebirths in the lower realms. In Western societies, the distinction between pride Karine LePajolec and firmness of mind is often confused. A lack of pride is construed to be a weakness. Pride is a built- up and concentrated form of ego grasping. So in this respect, it is a weakness. A person can have great strength of character, and a strong resolve to achieve a type of thought and try to see what it looks like a goal, such as enlightenment, for example, without and where it comes from. Does it come from the per- pride ever manifesting. son or from yourself? If you think it comes from the We need to dissociate pride — the affirmation of our mind, where does it arise from, how does it remain, own supremacy over others, which suggests a certain and where does it go when it disappears? In this way blindness — from firmness of mind that is a quality one takes the anger itself as the object of meditation free of all the negative aspects and reflection. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

On Local Festival Performance: The Sherpa Dumji in a world of dramatically increasing uncertainties1 Eberhard Berg It is important to remember, however, that Tibetan Buddhism, especially the form followed by the Rnying ma pa, is intended first and foremost to be pragmatic (...). The explanation for the multiplicity of metaphors and tutelary deities lies in the fact that there must be a practice suited to every sentient creature somewhere. Forms or metaphors that were relevant yesterday may lose their efficacy in the changed situation of today. E.G. Smith (2001:240) The Sherpas are a small, ethnically Tibetan people who live at high altitudes in the environs of Mt. Everest in Solu-Khumbu, a relatively remote area in the north eastern part of the “Hindu Kingdom of Nepal”. Traditionally, their economy has combined agriculture with herding and local as well as long- distance trade. Since the middle of the 20th century they have been successfully engaged in the trekking and mountaineering boom. Organised in patrilineal clans, they live in nuclear family households in small villages, hamlets, and isolated homesteads. Property in the form of herds, houses and land is owned by nuclear families. Among the Sherpas, Dumji, the famous masked dance festival, is held annually in the village temple of only eight local communities in Solu- Khumbu. According to lamas and laypeople alike Dumji represents the most important village celebration in the Sherpas’ annual cycle of ceremonies. The celebration of the Dumji festival is reflective of both Tibetan Buddhism and its supremacy over authochtonous belief systems, and the way a local community constructs, reaffirms and represents its own distinct local 1 I would like to thank the Sherpa community of the Lamaserwa clan, to their village lama, Lama Tenzing, who presides over the Dumji festival, and the ritual performers who assist him, and the Lama of Serlo Gompa, Ven. -

Social Manifestations of XIV Shamar Rinpoche Posthumous Activity

International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research IPEDR vol.83 (2015) © (2015) IACSIT Press, Singapore Social manifestations of XIV Shamar Rinpoche posthumous activity Malwina Krajewska Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun, Poland Abstract. This paper analyze and present social phenomena which appeared after the sudden death of Tibetan Lama- XIV Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche Mipham Chokyi Lodro. It contain ethnographic descriptions and reflections made during anthropological fieldwork in Germany as well in Nepal. It shows how Buddhist teacher can influence his practitioners even after death. What is more this paper provide reliable information about the role of Shamarpa in Kagyu tradition. Keywords: Anthropology, Buddhism, Fieldwork, Cremation. 1. Introduction Information and reflections published in this paper are an attempt to present anthropological approach to current and global situation of one specific tradition within Tibetan Buddhism. The sudden death of Kagyu tradition Lineage Holder- Shamarpa influenced many people from America, Asia, Australia and Europe and Russia. In following section of this article you will find examples of social phenomena connected to this situation, as well basic information about Kagyu tradition. 2. Cremation at Shar Minub Monastery 31 of July 2014 was very hot and sunny day (more than 30 degrees) in Kathmandu, Nepal. Thousands of people gathered at Shar Minub Monastery and in its surroundings. On the rooftop of unfinished (still under construction) main building you could see a crowd of high Tibetan Buddhist Rinpoches and Lamas - representing different Tibetan Buddhist traditions. All of them were simultaneously leading pujas and various rituals. Among them Shamarpa family members as well as other noble guests were also present. -

JCPOA and the IAEA: Challenges Ahead

IDSA Issue Brief Emerging Flashpoints in the Himalayas P. Stobdan May 18, 2016 Summary Abstract: Long-term stability on both sides of the Himalayas cannot be achieved without working together or seeking coordinated policies. It is time to bring together the interests of both the Indian and Chinese governments toward seeking the common goal of saving the Himalayas and the people living in the region. EMERGING FLASHPOINTS IN THE HIMALAYAS Flashpoints in the Himalayan region are rising. The US Defence Department has expressed caution about China’s increased troops build-up along the Indian border as well as the likelihood of China establishing “additional naval logistic hubs” in Pakistan.1 From the Chinese perspective, the spectre of jihadi terrorism is spreading across Xinjiang province. The monks in Tibet continue to resist China’s military suppression. Pakistan, for its part, continues to sponsor terrorism in Kashmir with China’s tacit support. In Nepal, the vortex of the political crisis refuses to stop. This trend of events unfolding on both sides of the Himalayas is forming an interconnected chain. The issues involved transcend rugged mountains and even well-drawn cartographic and military lines. Signs of instability on one side impacting on another are visible. One would have hardly imagined that China’s dissenters, Uighurs and Tibetans could meet on this side of the Himalayas.2 Conventional wisdom had the Indian Himalayan belt being at least peaceful. Conviction also explained that freedom of religion (Buddhism) has ensured stability on this side of the mountain range. This sadly is no longer the case. The entire belt from Tawang to Ladakh has been subject to a string of incendiary events threatening to pitchfork the region into crisis. -

Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Sumy State University Institutional Repository SocioEconomic Challenges, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2019 ISSN (print) – 2520-6621, ISSN (online) – 2520-6214 Mainstream Religious Domain in Nepal a Contradiction and Conflict of Indigenous Communities in Maintaining the Identity, Race, Gender and Class https://doi.org/10.21272/sec.3(1).99-115.2019 Medani P. Bhandari PhD, Professor and Deputy Program Director of Sustainability Studies, Akamai University, Hawaii, USA, Professor of Economics and Entrepreneurships, Sumy State University, Ukraine Nepal is certainly one of the more romanticized places on earth, with its towering Himalayas, its abomi- nable snowmen, and its musically named capital, Kathmandu, a symbol of all those faraway places the imperial imagination dreamt about. And the Sherpa people ... are perhaps one of the more romanticized people of the world, renowned for their mountaineering feats, and found congeal by Westerners tour their warm, friendly, strong, self-confident style" (Sherry Ortner, 1978: 10). “All Nepalese, whether they realize it or not, are immensely sophisticated in their knowledge and appreciation cultural differences. It is a rare Nepalese indeed who knows how to speak only one language” (James Fisher 1987:33). Abstract Nepal is unique in terms of culture, religion, and geography as well as in its Indigenous Communities (IC). There has always been domination by the mainstream culture and religion; however, until recently there was no visible friction and violence between any religious groups and ICs. Within the societal structure, there was an effort to maintain harmonious relationships, at least on the surface. -

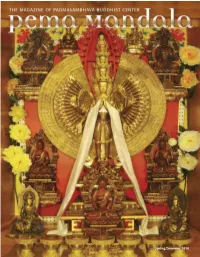

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher.