Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 29 August 2019] P6127c

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

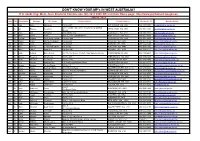

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

APR 2017-07 Winter Cover FA.Indd

Printer to adjust spine as necessary Australasian Parliamentary Review Parliamentary Australasian Australasian Parliamentary Review JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP Editor Colleen Lewis Fifty Shades of Grey(hounds) AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 Federal and WA Elections Off Shore, Out of Reach? • VOL 32 NO 32 1 VOL AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 • VOL 32 NO 1 • RRP $A35 AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (ASPG) AND THE AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW (APR) APR is the official journal of ASPG which was formed in 1978 for the purpose of encouraging and stimulating research, writing and teaching about parliamentary institutions in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific Membership of the Australasian Study of (see back page for Notes to Contributors to the journal and details of AGPS membership, which includes a subscription to APR). To know more about the ASPG, including its Executive membership and its Chapters, Parliament Group go to www.aspg.org.au Australasian Parliamentary Review Membership Editor: Dr Colleen Lewis, [email protected] The ASPG provides an outstanding opportunity to establish links with others in the parliamentary community. Membership includes: Editorial Board • Subscription to the ASPG Journal Australasian Parliamentary Review; Dr Peter Aimer, University of Auckland Dr Stephen Redenbach, Parliament of Victoria • Concessional rates for the ASPG Conference; and Jennifer Aldred, Public and Regulatory Policy Consultant Dr Paul Reynolds, Parliament of Queensland • Participation in local Chapter events. Dr David Clune, University of Sydney Kirsten Robinson, Parliament of Western Australia Dr Ken Coghill, Monash University Kevin Rozzoli, University of Sydney Rates for membership Prof. Brian Costar, Swinburne University of Technology Prof. -

Mr Yaz Mubarakai, MLA (Member for Jandakot)

PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INAUGURAL SPEECH Mr Yaz Mubarakai, MLA (Member for Jandakot) Legislative Assembly Address-in-Reply Thursday, 25 May 2017 Reprinted from Hansard Legislative Assembly Thursday, 25 May 2017 ____________ ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 18 May on the following motion moved by Ms J.J. Shaw — That the following Address-in-Reply to Her Excellency’s speech be agreed to — To Her Excellency the Honourable Kerry Sanderson, AC, Governor of the State of Western Australia. May it please Your Excellency — We, the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of the State of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express loyalty to our Most Gracious Sovereign and to thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to address to Parliament. INTRODUCTION MR Y. MUBARAKAI (Jandakot) [2.54 pm]: Mr Speaker, thank you, and please let me congratulate you on your election to the position of Speaker of this house. I would like to begin by acknowledging the Whadjuk Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, and pay my respects to their elders past, present, and future. To Mark McGowan, Premier of Western Australia and proud leader of the Western Australian Labor Party, I say thank you and congratulations! It was your clear vision for this state, and your strong leadership and tireless efforts that led to the formation of this new government in emphatic style, and I am honoured to be part of a team that will roll up its sleeves and work to deliver that vision for all Western Australians. -

Western Australia Ministry List 2021

Western Australia Ministry List 2021 Minister Portfolio Hon. Mark McGowan MLA Premier Treasurer Minister for Public Sector Management Minister for Federal-State Relations Hon. Roger Cook MLA Deputy Premier Minister for Health Minister for Medical Research Minister for State Development, Jobs and Trade Minister for Science Hon. Sue Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Stephen Dawson MLC Minister for Mental Health Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Industrial Relations Deputy Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development Minister for Agriculture and Food Minister Assisting the Minister for State Development for Hydrogen Hon. David Templeman MLA Minister for Tourism Minister for Culture and the Arts Minister for Heritage Leader of the House Hon. John Quigley MLA Attorney General Minister for Electoral Affairs Minister Portfolio Hon. Paul Papalia MLA Minister for Police Minister for Road Safety Minister for Defence Industry Minister for Veterans’ Issues Hon. Bill Johnston MLA Minister for Mines and Petroleum Minister for Energy Minister for Corrective Services Hon. Rita Saffioti MLA Minister for Transport Minister for Planning Minister for Ports Hon. Dr Tony Buti MLA Minister for Finance Minister for Lands Minister for Sport and Recreation Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Interests Hon. Simone McGurk MLA Minister for Child Protection Minister for Women’s Interests Minister for Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence Minister for Community Services Hon. Dave Kelly MLA Minister for Water Minister for Forestry Minister for Youth Hon. Amber-Jade Sanderson Minister for Environment MLA Minister for Climate Action Minister for Commerce Hon. -

Greyhounds - Namely That Similar to the Recent Changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW

From: Subject: I support an end to compulsory greyhound muzzling Date: Sunday, 28 July 2019 10:52:22 PM Dear Peter Rundle MP, cc: Cat and Dog statutory review I would like to express my support for the complete removal of the section 33(1) of the Dog Act 1976 in relation to companion pet greyhounds - namely that similar to the recent changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW. I believe companion greyhounds should be allowed to go muzzle free in public without the requirement to complete a training programme. I have owned my own greyhound for two years and find the muzzle is not needed or necessary in actual fact I’ve seen other dog breeds aggressively attacking. I support the removal of this law for companion pet greyhounds for the following reasons: 1. Greyhounds are kept as pets in countries all over the world muzzle free and there has been no increased incidence of greyhound dog bites to people, other dogs or animals 2. The RSPCA have found no evidence to suggest that greyhounds as a breed pose any greater risk than other dog breeds 3. Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania are the only Australian states still with this law. All other states (VIC, NSW, QLD, ACT, NT) have removed this law 4. The view supported by veterinary behaviourists is that the behaviour of a particular dog should be based on that individual dogs attributes not its breed 5. As a breed, greyhounds are known for their generally friendly and gentle disposition, even despite their upbringing in the racing industry 6. -

Suicides, Assisted Suicides And'mercy Killings': Would

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Del Villar, Katrine, Willmott, Lindy,& White, Ben (2020) Suicides, Assisted Suicides and ’Mercy Killings’: Would Voluntary Assisted Dying Prevent these ’Bad Deaths’? Monash University Law Review, 46(2). (In Press) This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/199576/ c Monash University Press This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. SUICIDES, ASSISTED SUICIDES AND ‘MERCY KILLINGS’: WOULD VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING PREVENT THESE ‘BAD DEATHS’? Katrine Del Villar, Lindy Willmott and Ben White1 This article may be cited as: (2020) 46(2) Monash University Law Review (forthcoming) Abstract Voluntary assisted dying (VAD) has recently been legalised in Victoria, and legalisation is being considered in other Australian States. -

Mr Shane Love; Mr Zak Kirkup; Ms Emily Hamilton; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Mr Simon Millman; Mr Ben Wyatt

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 16 May 2019] p3575b-3596a Mrs Robyn Clarke; Mr Shane Love; Mr Zak Kirkup; Ms Emily Hamilton; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Mr Simon Millman; Mr Ben Wyatt APPROPRIATION (RECURRENT 2019–20) BILL 2019 APPROPRIATION (CAPITAL 2019–20) BILL 2019 Second Reading — Cognate Debate Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MRS R.M.J. CLARKE (Murray–Wellington) [3.33 pm]: I would like to lead off from where I finished before the lunch break. Across my electorate are beautiful and environmentally important waterways. The protection of these waterways is so important to the local community and the environment, and we are ensuring that the fragile environment receives the support that it needs. Funds of $1.2 million have already been invested in protecting the Peel–Harvey estuary, as well as $10.5 million for the establishment and management of the Preston River to Ocean and Leschenault Regional Parks programs. Protecting the unique biodiversity of the Peel and the south west is essential to the livelihood of the areas and to tourism. This funding will ensure that local waterways can be enjoyed for years to come. Agriculture is a major industry throughout my electorate. It is being supported through an additional $131.5 million in funding to help grow our export markets and create long-term jobs. This includes just under $40 million towards boosting biosecurity defences, Asian market success, and grains research and development support programs. These programs, alongside the ongoing WA Open for Business program, deliver essential backing to regional economies. Providing assistance to open up new export opportunities within agricultural industries creates ongoing jobs for people in the regions and allows local small businesses to achieve growth that may have previously been unattainable. -

Mcgowan Government Cabinet Hon Mark Mcgowan MLA

McGowan Government Cabinet Hon Mark McGowan MLA Premier; Treasurer; Minister for Public Sector Management; Federal-State Relations Hon Roger Cook MLA Deputy Premier; Minister for Health; Medical Research; State Development, Jobs and Trade; Science Hon Sue Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training; Leader of the Legislative Council Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Minister for Mental Health; Aboriginal Affairs; Industrial Relations; Deputy Leader of the Legislative Council Hon Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development; Agriculture and Food; Hydrogen Industry Hon David Templeman MLA Minister for Tourism; Culture and the Arts; Heritage; Leader of the House Hon John Quigley MLA Attorney General; Minister for Electoral Affairs Hon Paul Papalia MLA Minister for Police; Road Safety; Defence Industry; Veterans Issues Hon Bill Johnston MLA Minister for Mines and Petroleum; Energy; Corrective Services Hon Rita Saffioti MLA Minister for Transport; Planning; Ports Hon Dr Tony Buti MLA Minister for Finance; Lands; Sport and Recreation; Citizenship and Multicultural Interests Hon Simone McGurk MLA Minister for Child Protection; Women's Interests; Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence; Community Services Hon Dave Kelly MLA Minister for Water; Forestry; Youth Hon Amber-Jade Sanderson Minister for Environment; Climate Action; Commerce MLA Hon John Carey MLA Minister for Housing; Local Government Hon Don Punch MLA Minister for Disability Services; Fisheries; Innovation and ICT; Seniors and Ageing Hon Reece Whitby MLA Minister for Emergency -

WA State Election 2017

PARLIAMENTAR~RARY ~ WESTERN AUSTRALIA 2017 Western Australian State Election Analysis of Results Election Papers Series No. 1I2017 PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN AUSTRALIAN STATE ELECTION 2017 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS by Antony Green for the Western Australian Parliamentary Library and Information Services Election Papers Series No. 1/2017 2017 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, Western Australian Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the Western Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Australian Parliamentary Library. Western Australian Parliamentary Library Parliament House Harvest Terrace Perth WA 6000 ISBN 9780987596994 May 2017 Related Publications • 2015 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2015. • Western Australian State Election 2013 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2013. • 2011 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2011. • Western Australian State Election 2008 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2009. • 2007 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2007 • Western Australian State Election 2005 - Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2005. • 2003 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2003. -

Greyhounds Date: Wednesday, 17 July 2019 11:59:26 PM

From: To: Cat&DogReview Subject: End forced muzzling of greyhounds Date: Wednesday, 17 July 2019 11:59:26 PM As a breed, greyhounds are some of the sweetest dogs on earth. The RSPCA and leading veterinarians agree that it’s time for state law to stop discriminating against greyhounds. Given the high “wastage” (kill) rate of ex-racing dogs Down Under, everything should be done to promote adoption, including letting people see just how wonderful these dogs are. PLEASE amend the Dog Act to remove misguided, breed-specific language requiring greyhound muzzling. Thank You/ From: To: Cat&DogReview Date: Wednesday, 17 July 2019 11:58:51 PM Please stop muzzling retired greyhounds they don't deserve this kind.of treatment. Thought better of your country From: To: Cat&DogReview Subject: Muzzling of Greyhounds Date: Wednesday, 17 July 2019 11:58:32 PM Please stop the practice of muzzling the Greyhounds. They are sweet, intelligent dogs that go through enough abuse, and don’t need to be treated so cruelly. Thank you! Sent from my iPhone From: To: Cat&DogReview Date: Wednesday, 17 July 2019 11:58:15 PM Stop muzzling adopted greyhounds. Didn't they suffer enough racing? It is really disgusting what people do to animals all over the world and how the governments allow it. It is very disturbing that you won't let these beautiful animals enjoy their lives. Please end this persecution now. They are not vicious and should not have to wear muzzles when they finally have a loving home. Thank you for doing the right thing. -

P675a-687A Mr David Templeman; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Mr Sean L'estrange; Mr Dean Nalder

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 25 May 2017] p675a-687a Mr David Templeman; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Mr Dean Nalder ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MR D.A. TEMPLEMAN (Mandurah — Leader of the House) [2.54 pm]: Before the break I had reported to the house about the naming of the new Mandurah bridge. I now conclude my remarks. The SPEAKER: I give the call to the member for Jandakot. [Applause.] MR Y. MUBARAKAI (Jandakot) [2.54 pm]: Mr Speaker, thank you, and please let me congratulate you on your election to the position of Speaker of this house. I would like to begin by acknowledging the Whadjuk Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, and pay my respects to their elders past, present, and future. To Mark McGowan, Premier of Western Australia and proud leader of the Western Australian Labor Party, I say thank you and congratulations! It was your clear vision for this state, and your strong leadership and tireless efforts that led to the formation of this new government in emphatic style, and I am honoured to be part of a team that will roll up its sleeves and work to deliver that vision for all Western Australians. I would also like to acknowledge Hon Sue Ellery as the first female Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council, and Hon Kate Doust, who has been elected as the first female President of the Legislative Council. Congratulations. This is a win for diversity and equality! I look around this chamber today, and I know that I am amongst an unprecedented number of new members, each of whom I would like to congratulate, along with my colleagues who have been returned for another term and are now in government.