Suicides, Assisted Suicides And'mercy Killings': Would

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No 85 — Thursday 26 November 2020 1 The House met in accordance with the terms of the resolution on 24 November 2020 — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 PETITION — The Clerk announced that the following petition had been lodged for presentation: Reinstate Warneet Jetties by 2021 — Requesting that Parks Victoria reinstate the entire Warneet North Jetty and the southern end of the Warneet South Jetty to a safe and usable condition by 1 January 2021, bearing 860 signatures (Mr Burgess). Ordered to be tabled. 3 PETITION — REINSTATE WARNEET JETTIES BY 2021 — Motion made and question — That the petition presented by the Member for Hastings be taken into consideration tomorrow (Mr Smith, Warrandyte) — put and agreed to. 4 DOCUMENTS TABLED UNDER ACTS OF PARLIAMENT — The Clerk tabled the following documents under Acts of Parliament: Cenitex — Report 2019–20 Gambling Regulation Act 2003 — Review of Part 6A of the Point of Consumption Tax on wagering and betting Local Jobs First — Report 2019–20 Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 — No Jab No Play 2020 review under s 149A. 5 MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR — Recommending an appropriation for the purposes of the State Taxation Acts Amendment Bill 2020. 6 ENVIRONMENT AND PLANNING STANDING COMMITTEE — The Speaker announced that he had received the resignation of Mr Cheeseman from the Environment and Planning Standing Committee, effective from 25 November 2020. 2 Legislative Assembly of Victoria -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 47, 48 and 49 No 47 — Tuesday 26 November 2019 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 GREAT OCEAN ROAD AND ENVIRONS PROTECTION BILL 2019 — Ms D’Ambrosio obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to recognise the importance of the landscapes and seascapes along the Great Ocean Road to the economic prosperity and liveability of Victoria and as one living and integrated natural entity for the purposes of protecting the region, to establish a Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority to which various land management responsibilities are to be transferred and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 4 ROAD SAFETY AND OTHER LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2019 — Ms Neville obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Road Safety Act 1986 to provide for immediate licence or permit suspensions in certain cases and to make consequential and related amendments to that Act and to make minor amendments to the Sentencing Act 1991 and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 GENDER EQUALITY BILL 2019 — Ms Williams obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to require the public sector, Councils and universities to promote gender equality, to take positive action towards achieving gender equality, to establish the Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. -

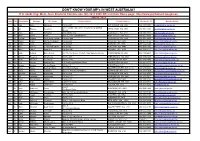

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

6 April to 15 May 2017 Letter From

Issue 89 6 April to 15 May 2017 Letter from CanberrSaving you time for nine years. a Cold Autumn Edition • 18 C (free speech and similar). • Keating and others on Housing • A not-strong energy system, grid and all • Gas and cattle • Sally McManus In This Issue • More on free speech • Housing. Housing • Hawke Beer Letter From Canberra // Issue 90 Letter from Saving you time for nine years. CanberrA monthly digest of news from around Australia. a Saving you time; now in its ninth year. About Us CONTENTS Media .....................................................10 Affairs of State 43 Richmond Terrace Editorial ....................................................3 IT ............................................................10 Richmond, Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Governance ..............................................3 Immigration ...........................................10 P +61 408 033 110 [email protected] The Budget ................................................3 Justice .....................................................10 www.affairs.com.au Party Happenings .................................. 4 Housing ..................................................10 Letter From Canberra is a monthly public affairs bulletin, a simple précis, distilling and Industrial Relations and Employment . 5 Welfare ................................................... 11 interpreting public policy and government decisions, which affect business oppor- Business, Economy, Manufacturing and Transport ............................................... -

Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 www.leadlm.org.au 03 5442 6047 [email protected] CONTENTS Chair's Report 1. Treasurer's Report 2. Executive Officer's Report 3. Audited Financial 4. Statements Report on Activities 24. CHAIR’S REPORT I am delighted to present LEAD Loddon Murray’s Annual Report for the year ended December 31, 2018. This year marked our 21st Birthday. 21 Years of continuous investment in developing leaders was and is continually worth celebrating. We secured a grant from the Australian Government’s Building Better Region’s Fund and delivered a one-day Regional Leaders Convention and 21st Birthday Gala Dinner, in place of our long-standing Vision of the Region Dinner. We were thrilled to be able to extend the Vision of the Region into a day long conversation, taking a deep dive into our region’s future economy, global relationships, technology infrastructure and services and environmental management and to ask- what’s the lens for leaders here? We plan to build on the success of this format in 2019. Change like last year has been a major theme for us all in community leadership, irrespective of which sector or role we serve in, change is continual and constant for us all as humans, not just as leaders. LEAD Loddon Murray proudly took residence in our own office space last year which has provided a strong base for our team and board to work from. In 2018, the Board of Management and Team wished Jo Cahill a happy farewell as she went on leave in preparation to have her first baby Isabelle and we welcomed in Jude Hannah as incoming LMCLP Program Manager. -

APR 2017-07 Winter Cover FA.Indd

Printer to adjust spine as necessary Australasian Parliamentary Review Parliamentary Australasian Australasian Parliamentary Review JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP Editor Colleen Lewis Fifty Shades of Grey(hounds) AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 Federal and WA Elections Off Shore, Out of Reach? • VOL 32 NO 32 1 VOL AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 • VOL 32 NO 1 • RRP $A35 AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (ASPG) AND THE AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW (APR) APR is the official journal of ASPG which was formed in 1978 for the purpose of encouraging and stimulating research, writing and teaching about parliamentary institutions in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific Membership of the Australasian Study of (see back page for Notes to Contributors to the journal and details of AGPS membership, which includes a subscription to APR). To know more about the ASPG, including its Executive membership and its Chapters, Parliament Group go to www.aspg.org.au Australasian Parliamentary Review Membership Editor: Dr Colleen Lewis, [email protected] The ASPG provides an outstanding opportunity to establish links with others in the parliamentary community. Membership includes: Editorial Board • Subscription to the ASPG Journal Australasian Parliamentary Review; Dr Peter Aimer, University of Auckland Dr Stephen Redenbach, Parliament of Victoria • Concessional rates for the ASPG Conference; and Jennifer Aldred, Public and Regulatory Policy Consultant Dr Paul Reynolds, Parliament of Queensland • Participation in local Chapter events. Dr David Clune, University of Sydney Kirsten Robinson, Parliament of Western Australia Dr Ken Coghill, Monash University Kevin Rozzoli, University of Sydney Rates for membership Prof. Brian Costar, Swinburne University of Technology Prof. -

Mr Yaz Mubarakai, MLA (Member for Jandakot)

PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INAUGURAL SPEECH Mr Yaz Mubarakai, MLA (Member for Jandakot) Legislative Assembly Address-in-Reply Thursday, 25 May 2017 Reprinted from Hansard Legislative Assembly Thursday, 25 May 2017 ____________ ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 18 May on the following motion moved by Ms J.J. Shaw — That the following Address-in-Reply to Her Excellency’s speech be agreed to — To Her Excellency the Honourable Kerry Sanderson, AC, Governor of the State of Western Australia. May it please Your Excellency — We, the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of the State of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express loyalty to our Most Gracious Sovereign and to thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to address to Parliament. INTRODUCTION MR Y. MUBARAKAI (Jandakot) [2.54 pm]: Mr Speaker, thank you, and please let me congratulate you on your election to the position of Speaker of this house. I would like to begin by acknowledging the Whadjuk Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, and pay my respects to their elders past, present, and future. To Mark McGowan, Premier of Western Australia and proud leader of the Western Australian Labor Party, I say thank you and congratulations! It was your clear vision for this state, and your strong leadership and tireless efforts that led to the formation of this new government in emphatic style, and I am honoured to be part of a team that will roll up its sleeves and work to deliver that vision for all Western Australians. -

Western Australia Ministry List 2021

Western Australia Ministry List 2021 Minister Portfolio Hon. Mark McGowan MLA Premier Treasurer Minister for Public Sector Management Minister for Federal-State Relations Hon. Roger Cook MLA Deputy Premier Minister for Health Minister for Medical Research Minister for State Development, Jobs and Trade Minister for Science Hon. Sue Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Stephen Dawson MLC Minister for Mental Health Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Industrial Relations Deputy Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development Minister for Agriculture and Food Minister Assisting the Minister for State Development for Hydrogen Hon. David Templeman MLA Minister for Tourism Minister for Culture and the Arts Minister for Heritage Leader of the House Hon. John Quigley MLA Attorney General Minister for Electoral Affairs Minister Portfolio Hon. Paul Papalia MLA Minister for Police Minister for Road Safety Minister for Defence Industry Minister for Veterans’ Issues Hon. Bill Johnston MLA Minister for Mines and Petroleum Minister for Energy Minister for Corrective Services Hon. Rita Saffioti MLA Minister for Transport Minister for Planning Minister for Ports Hon. Dr Tony Buti MLA Minister for Finance Minister for Lands Minister for Sport and Recreation Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Interests Hon. Simone McGurk MLA Minister for Child Protection Minister for Women’s Interests Minister for Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence Minister for Community Services Hon. Dave Kelly MLA Minister for Water Minister for Forestry Minister for Youth Hon. Amber-Jade Sanderson Minister for Environment MLA Minister for Climate Action Minister for Commerce Hon. -

Greyhounds - Namely That Similar to the Recent Changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW

From: Subject: I support an end to compulsory greyhound muzzling Date: Sunday, 28 July 2019 10:52:22 PM Dear Peter Rundle MP, cc: Cat and Dog statutory review I would like to express my support for the complete removal of the section 33(1) of the Dog Act 1976 in relation to companion pet greyhounds - namely that similar to the recent changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW. I believe companion greyhounds should be allowed to go muzzle free in public without the requirement to complete a training programme. I have owned my own greyhound for two years and find the muzzle is not needed or necessary in actual fact I’ve seen other dog breeds aggressively attacking. I support the removal of this law for companion pet greyhounds for the following reasons: 1. Greyhounds are kept as pets in countries all over the world muzzle free and there has been no increased incidence of greyhound dog bites to people, other dogs or animals 2. The RSPCA have found no evidence to suggest that greyhounds as a breed pose any greater risk than other dog breeds 3. Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania are the only Australian states still with this law. All other states (VIC, NSW, QLD, ACT, NT) have removed this law 4. The view supported by veterinary behaviourists is that the behaviour of a particular dog should be based on that individual dogs attributes not its breed 5. As a breed, greyhounds are known for their generally friendly and gentle disposition, even despite their upbringing in the racing industry 6. -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National