Revisiting Shakespeare's Lost Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

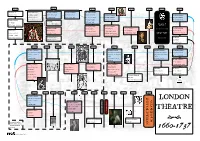

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

A Christian Hero at Drury Lane

DL Layout NEW_Layout 1 05/04/2013 10:03 Page 129 9 A Christian Hero at Drury Lane hen Christopher Rich was kicked out of Drury Lane, everyone assumed that would be the end of his troublesome Wcareer in the London theatre. Rich, however, was a man who seemed to be constitutionally incapable of even contemplating defeat, so when he realised that his time at Drury Lane was at an end, he turned his attention to the theatre that was now standing empty in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. From as far back as 1708, when things were getting rocky, Rich had been paying rent on the Lincoln’s Inn Fields building, which had been unused since Betterton took his company to the Haymarket in 1705. With Drury Lane now occupied by his enemies, Rich began what was virtually a reconstruction of the old tennis court to turn it into a serious rival to his former theatre. ere was one huge problem: although he held both patents issued by Charles II, he had been silenced, so even if he had a theatre, he couldn’t put on plays. However, with a new monarch on the throne and a new Lord Chamberlain in office, he thought he would try again, and he got one of his well-connected investors in the Lincoln’s Inn Fields project to speak to the King. George I probably knew little and cared less about Rich’s management of Drury Lane, and simply said that, when he used to visit London as a young 129 DL Layout NEW_Layout 1 05/04/2013 10:03 Page 130 THE OTHER NATIONAL THEATRE man, there were two theatres, and he didn’t see why there shouldn’t be two theatres again. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS DURING THE STRUGGLE FOR CONTROL OF THE LONDON THEATRE, 1695-1710 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Jay Edw ard Oney, B.A., M.A. -

Ballad Opera in England: Its Songs, Contributors, and Influence

BALLAD OPERA IN ENGLAND: ITS SONGS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND INFLUENCE Julie Bumpus A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 7, 2010 Committee: Vincent Corrigan, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Vincent Corrigan, Advisor The ballad opera was a popular genre of stage entertainment in England that flourished roughly from 1728 (beginning with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera) to 1760. Gay's original intention for the genre was to satirize not only the upper crust of British society, but also to mock the “excesses” of Italian opera, which had slowly been infiltrating the concert life of Britain. The Beggar's Opera and its successors were to be the answer to foreign opera on British soil: a truly nationalistic genre that essentially was a play (building on a long-standing tradition of English drama) with popular music interspersed throughout. My thesis explores the ways in which ballad operas were constructed, what meanings the songs may have held for playwrights and audiences, and what influence the genre had in England and abroad. The thesis begins with a general survey of the origins of ballad opera, covering theater music during the Commonwealth, Restoration theatre, the influence of Italian Opera in England, and The Beggar’s Opera. Next is a section on the playwrights and composers of ballad opera. The playwrights discussed are John Gay, Henry Fielding, and Colley Cibber. Purcell and Handel are used as examples of composers of source material and Mr. Seedo and Pepusch as composers and arrangers of ballad opera music. -

Pregnancy and Performance on the British Stage in the Long Eighteenth Century, 1689-1807

“Carrying All Before Her:” Pregnancy and Performance on the British Stage in the Long Eighteenth Century, 1689-1807 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chelsea Phillips, MFA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Lesley Ferris, Advisor; Dr. Jennifer Schlueter; Dr. Stratos Constantinidis; Dr. David Brewer Copyright by Chelsea Lenn Phillips 2015 ABSTRACT Though bracketed by centuries of greater social restrictions, the long eighteenth century stands as a moment in time when women enjoyed a considerable measure of agency and social acceptance during pregnancy. In part, this social acceptance rose along with birth rates: the average woman living in the eighteenth century gave birth to between four and eight children in her lifetime. As women spent more of their adult lives pregnant, and as childbearing came to be considered less in the light of ritual and more in the light of natural phenomenon, social acceptance of pregnant women and their bodies increased. In this same century, an important shift was occurring in the professional British theatre. The eighteenth century saw a rise in the respectability of acting as a profession generally, and of the celebrity stage actress in particular. Respectability does not mean passivity, however—theatre historian Robert Hume describes the history of commercial theatre in eighteenth century London as a “vivid story of ongoing competition, sometimes fierce, even destructive competition.”1 Theatrical managers deployed their most popular performers and entertainments strategically, altering the company’s repertory to take advantage of popular trends, illness or scandal in their competition, or to capitalize on rivalries. -

John Larpent Plays

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1h4n985c No online items John Larpent Plays Processed by Dougald MacMillan in 1939; supplementary encoding and revision by Diann Benti in January 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2000 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. John Larpent Plays mssLA 1-2503 1 Overview of the Collection Title: John Larpent Plays Dates (inclusive): 1737-1824 Collection Number: mssLA 1-2503 Creator: Larpent, John, 1741-1824. Extent: 2,503 pieces. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of official manuscript copies of plays submitted for licensing in Great Britain between 1737 and 1824 that were in the possession of John Larpent (1741-1824), the examiner of plays, at the time of his death in 1824. The collection includes 2,399 identified plays as well as an additional 104 unidentified pieces including addresses, prologues, epilogues, etc. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

The Re-Creation of Early English Pantomime

Bill Tuck, Experiments in the reconstruction of early 18th century English pantomime, Mummers Unconvention, Bath, 2011. Experiments in the reconstruction of early 18th century English pantomime Introduction It has long been recognized that the story of Perseus and Andromeda closely matches the folk-tale of St George and the Dragon. In both, our hero slays a monster to free the King of Egypt’s (or Ethiopia’s) daughter, who has been chained to a rock as a sacrificial offering to the beast. The grateful King then grants our hero her hand in marriage. What is more difficult to show is any direct link between the Greek Myth and the Mummers’ Play (in all its various guises). It is generally held that the earliest text of a folk-play performance is from 1780, the earliest chapbook text from the middle decades of the eighteenth century, while the earliest reliable description of a performance resembling the modern folk-play takes us back only as far as 17371. One possible connection that has yet to be explored is through the English pantomime tradition that originated on the London stage in the early 18th century, but migrated from there to provincial fairs and other performance spaces later in the century. The pantomime of Perseus and Andromeda was one of the most successful shows of this period (with several hundred performances between 1730 and 1780). Furthermore, at fairs, pantomime performances were often to be found in association with quack medicine sellers, who employed commedia characters as front-men for their operations. This may be one plausible origin for the ‘doctor’ character of the folk-play. -

The Chinese Festival and the Eighteenth-Century London Audience

The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 2.1.December 2008.31‐52. The Chinese Festival and the Eighteenth-Century London Audience Hsin-yun Ou ABSTRACT To illustrate the political, social and commercial significance of David Garrick’s Drury Lane theatre, this essay investigates the riot at The Chinese Festival (1755) and explores three major factors that merged to result in the ballet riot: first, English national animosity against France during the Seven Years’ War; second, English class warfare between the aristocratic fans of exoticism and the jingoistic mob; and third, Drury Lane Theatre’s competition not only with Covent Garden Theatre but also with the King’s Theatre. All these factors entangle with one another to influence the spectatorship and cultural production mode in eighteenth-century London theatres. From the perspective of cultural studies, this paper analyzes the theatre records and historical material to demonstrate that, in the case of the 1755 theatre riot, English patriotism was employed as a strategy for class struggle and theatre rivalry. KEY WORDS: the eighteenth century, London theatre, David Garrick, patriotism, class, spectatorship * Received: January 4, 2007; Accepted: November 19, 2007 Hsin-yun Ou, Assistant Professor, Department of Western Languages & Literature, National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] 32 The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 2.1.December 2008 David Garrick, the famous eighteenth-century English actor-manager, suffered from the greatest disaster in his career in November 1755. To reproduce the great spectacle of the French ballet Les Fêtes chinoises in London, Garrick engaged the choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre and the French designer Louis-René Boquet to stage The Chinese Festival at Drury Lane in November 1755. -

Colley Cibber - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Colley Cibber - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Colley Cibber(6 November 1671 – 11 December 1757) Colley Cibber was an English actor-manager, playwright and Poet Laureate. His colourful memoir Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber (1740) describes his life in a personal, anecdotal and even rambling style. He wrote 25 plays for his own company at Drury Lane, half of which were adapted from various sources, which led <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/robert-lowe/">Robert Lowe</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/alexander-pope/">Alexander Pope</a>, among others, to criticise his "miserable mutilation" of "crucified Molière [and] hapless Shakespeare". He regarded himself as first and foremost an actor and had great popular success in comical fop parts, while as a tragic actor he was persistent but much ridiculed. Cibber's brash, extroverted personality did not sit well with his contemporaries, and he was frequently accused of tasteless theatrical productions, shady business methods, and a social and political opportunism that was thought to have gained him the laureateship over far better poets. He rose to ignominious fame when he became the chief target, the head Dunce, of Alexander Pope's satirical poem Dunciad. Cibber's poetical work was derided in his time, and has been remembered only for being poor. His importance in British theatre history rests on his being one of the first in a long line of actor-managers, on the interest of two of his comedies as documents of evolving early 18th-century taste and ideology, and on the value of his autobiography as a historical source. -

Proquest Dissertations

THE FORTUNES OF KING LEAR IN LONDON BETWEEN 1681 AND 1838: â chronological account of its adaptors, actors and editors, and of the links between them. Penelope Hicks University College London Ph.D ProQuest Number: U642864 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642864 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis examines three interwoven strands in the dramatic and editorial history of King Lear between 1681 and 1838. One strand is the history of the adaptations which held the London stage during these years; the second is the changing styles of acting over the same period; the third is the work of the editors as they attempted to establish the Shakespearean text. This triple focus enables me to explore the paradoxical dominance of the adaptations at a time which saw both the text being edited for the first time and the rise of bardolatry. The three aspects of the fortunes ofKing Lear are linked in a number of ways, and I trace these connections as the editors, adaptors and actors concentrated on their own separate concerns. -

Slavery and the British Country House

Slavery and the British Country House Edited by Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann Slavery and the � British Country House � Edited by Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann Published by English Heritage, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH www.english-heritage.org.uk English Heritage is the Government’s lead body for the historic environment. © Individual authors 2013 The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and not necessarily those of English Heritage. Figures 2.2, 2.5, 2.6, 3.2, 3.16 and 12.9 are all based on Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100024900. First published 2013 ISBN 978 1 84802 064 1 Product code 51552 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. � The right of the authors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. � All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Application for the reproduction of images should be made to English Heritage. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and we apologise in advance for any unintentional omissions, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition of this book. For more information about images from the English Heritage Archive, contact Archives Services Team, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH; telephone (01793) 414600.