Evaluating the Attractiveness and Effectiveness of Artificial Coral Reefs As a Recreational Ecosystem Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. I NOV20 2017

or UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE / National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration * i. I NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE Southeast Regional Office 4rES O LQi 3U Ie1U SOU St. Petersburg, Florida 33701-5505 http://sero.nmfs.noaa.gov F/SER3 1: NMB SER-2015- 17616 NOV20 2017 Mr. Donald W. Kinard Chief, Regulatory Division U.S. Army Corps of Engineers P.O. Box 4970 Jacksonville, Florida 32232-0019 Ref.: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville District’s Programmatic Biological Opinion (JAXBO) Dear Mr. Kinard: Enclosed is the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS’s) Programmatic Biological Opinion (Opinion) based on our review of the impacts associated with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE’s) Jacksonville District’s authorization of 10 categories of minor in-water activities within Florida and the U.S. Caribbean (Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands). The Opinion analyzes the effects from 10 categories of minor in-water activities occurring in Florida and the U.S. Caribbean on sea turtles (loggerhead, leatherback, Kemp’s ridley, hawksbill, and green); smalitooth sawfish; Nassau grouper; scalloped hammerhead shark, Johnson’s seagrass; sturgeon (Gulf, shortnose, and Atlantic); corals (elkhom, staghorn, boulder star, mountainous star, lobed star, rough cactus, and pillar); whales (North Atlantic right whale, sei, blue, fin, and sperm); and designated critical habitat for Johnson’s seagrass; smalltooth sawfish; sturgeon (Gulf and Atlantic); sea turtles (green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead); North Atlantic right whale; and elkhorn and staghorn corals in accordance with Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act. We also analyzed effects on the proposed Bryde’s whale. -

A Numerical Assessment of Artificial Reef Pass Wave-Induced Currents As a Renewable Energy Source

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article A Numerical Assessment of Artificial Reef Pass Wave-Induced Currents as a Renewable Energy Source Damien Sous 1,2 1 Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO), Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, IRD, Université de Toulon, 13288 La Garde, France; [email protected]; Tel.: +33-(0)4-9114-2109 2 Univ Pau & Pays Adour/E2S UPPA, Chaire HPC-Waves, Laboratoire des Sciences de l’Ingénieur Appliquées à la Méchanique et au Génie Electrique - Fédération IPRA, EA4581, 64600 Anglet, France Received: 21 July 2019; Accepted: 19 August 2019; Published: 22 August 2019 Abstract: The present study aims to estimate the potential of artificial reef pass as a renewable source of energy. The overall idea is to mimic the functioning of natural reef–lagoon systems in which the cross-reef pressure gradient induced by wave breaking is able to drive an outward flow through the pass. The objective is to estimate the feasibility of a positive energy breakwater, combining the usual wave-sheltering function of immersed breakwater together with the production of renewable energy by turbines. A series of numerical simulations is performed using a depth-averaged model to understand the effects of each geometrical reef parameter on the reef–lagoon hydrodynamics. A synthetic wave and tide climate is then imposed to estimate the potential power production. An annual production between 50 and 70 MWh is estimated. Keywords: artificial reef; positive energy breakwater; numerical simulation; turbines 1. Introduction Low-lying nearshore areas host a significant and increasing population. Under the combined actions of sea level rise [1], modified storm patterns [2], and increasing urbanization, these regions will face growing risks of submersion, inundation, and erosion [3–6]. -

Harbor Protection Through Construction of Artificial Submerged Reefs

Harbor Protection through Construction of Artificial Submerged Reefs Amarjit Singh, Vallam Sundar, Enrique Alvarez, Roberto Porro, Michael Foley (www.hawaii.gov) 2 Outline • Background of Artificial Reefs • Multi-Purpose Artificial Submerged Reefs (MPASRs) ▫ Coastline Protection ▫ Harbor Protection • MPASR Concept for Kahului Harbor, Maui ▫ Situation ▫ Proposed Solution • Summary 3 Background First documented First specifically Artificial reefs in First artificial reef Artificial reefs in artificial reefs in designed artificial Hawaii– concrete/tire in Hawaii Hawaii – concrete Z- U.S. reefs in U.S. modules modules 1830’s 1961 1970’s 1985-1991 1991- Present • Uses • Materials ▫ Create Marine Habitat ▫ Rocks; Shells ▫ Enhance Fishing ▫ Trees ▫ Recreational Diving Sites ▫ Concrete Debris ▫ Surfing Enhancement ▫ Ships; Car bodies ▫ Coastal Protection ▫ Designed concrete modules ▫ Geosynthetic Materials 4 Multi-Purpose Artificial Submerged Reefs (MPASRs) Specifically designed artificial reef which can provide: • Coastline Protection or Harbor Protection ▫ Can help restore natural beach dynamics by preventing erosion ▫ Can reduce wave energy transmitted to harbor entrances • Marine Habitat Enhancement ▫ Can provide environment for coral growth and habitat fish and other marine species. ▫ Coral can be transplanted to initiate/accelerate coral growth • Recreational Uses ▫ Surfing enhancement: can provide surfable breaking waves where none exist ▫ Diving/Snorkeling: can provide site for recreational diving and snorkeling 5 MPASRs as Coastal Protection Wave Transmission: MPASRs can reduce wave energy transmitted to shoreline. Kt = Ht/Hi K = H /H t t i Breakwater K = wave transmission t Seabed coefficient, (Pilarczyk 2003) Ht= transmitted wave height shoreward of structure Hi = incident wave height seaward of structure. 6 MPASRs as Coastal Protection • Wave Refraction: MPASR causes wave refraction around the reef, focusing wave energy in a different direction. -

Review of Reef Effects of Offshore Wind Farm Strucurse and Potential for Enhancement and Mitigation

REVIEW OF REEF EFFECTS OF OFFSHORE WIND FARM STRUCTURES AND POTENTIAL FOR ENHANCEMENT AND MITIGATION JANUARY 2008 IN ASSOCIATION WITH Review of the reef effects of offshore wind farm structures and potential for enhancement and mitigation Report to the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform PML Applications Ltd in association with Scottish Association of Marine Sciences (SAMS) Contract No : RFCA/005/00029P This report may be cited as follows: Linley E.A.S., Wilding T.A., Black K., Hawkins A.J.S. and Mangi S. (2007). Review of the reef effects of offshore wind farm structures and their potential for enhancement and mitigation. Report from PML Applications Ltd and the Scottish Association for Marine Science to the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR), Contract No: RFCA/005/0029P Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The Review of Reef Effects of Offshore Wind Farm Structures and Potential for Enhancement and Mitigation was prepared by PML Applications Ltd and the Scottish Association for Marine Science. This project was undertaken as part of the UK Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR) offshore wind energy research programme, and managed on behalf of BERR by Hartley Anderson Ltd. We are particularly indebted to John Hartley and other members of the Research Advisory Group for their advice and guidance throughout the production of this report, and to Keith Hiscock and Antony Jensen who also provided detailed comment on early drafts. Numerous individuals have also contributed their advice, particularly in identifying data resources to assist with the analysis. We are particularly indebted to Angela Wratten, Chris Jenner, Tim Smyth, Mark Trimmer, Francis Bunker, Gero Vella, Robert Thornhill, Julie Drew, Adrian Maddocks, Robert Lillie, Tony Nott, Ben Barton, David Fletcher, John Leballeur, Laurie Ayling and Stephen Lockwood – who in the course of passing on information also contributed their ideas and thoughts. -

An Experimental Investigation of Turbulence Features Induced by Typical Artificial M-Shaped Unit Reefs

applied sciences Article An Experimental Investigation of Turbulence Features Induced by Typical Artificial M-Shaped Unit Reefs Anping Shu 1,*, Jiping Qin 1, Matteo Rubinato 2 , Tao Sun 1, Mengyao Wang 3, Shu Wang 1 , Le Wang 4 , Jiapin Zhu 1 and Fuyang Zhu 5 1 School of Environment, Key Laboratory of Water and Sediment Sciences of MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China; [email protected] (J.Q.); [email protected] (T.S.); [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (J.Z.) 2 School of Energy, Construction and Environment & Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Coventry University, Coventry CV1 5FB, UK; [email protected] 3 Beijing Water Resources Dispatching Center, Beijing 100038, China; [email protected] 4 School of Water Resources and Hydropower Engineering, North China Electric Power University, Beijing 102206, China; [email protected] 5 Power China Zhong Nan Engineering Corporation Limited, Changsha 410014, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-135-0117-6507 Abstract: Artificial reefs are considered to have the function of repairing and improving the coastal habitat and increasing the fishery production, which are mainly achieved by changing the regional hydrodynamic conditions. The characteristics of flow turbulence structure are an important part of the regional hydrodynamic characteristics. Different methods are used to evaluate the performance of artificial reefs according to their shape and the purpose for which the reef was built. For this study, the M-shaped unit reefs, which are to be put into the area of Liaodong Bay, were selected as the Citation: Shu, A.; Qin, J.; Rubinato, research object and have never been fully investigated before. -

Using Artificial-Reef Knowledge to Enhance the Ecological Function of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Implications for Fish A

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Review Using Artificial-Reef Knowledge to Enhance the Ecological Function of Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Implications for Fish Abundance and Diversity Maria Glarou 1,2,* , Martina Zrust 1 and Jon C. Svendsen 1 1 DTU Aqua, Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Kemitorvet, Building 202, 2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (J.C.S.) 2 Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, Svante Arrhenius väg 20 A (or F), 114 18 Stockholm, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-50174014 Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 5 May 2020; Published: 8 May 2020 Abstract: As the development of large-scale offshore wind farms (OWFs) amplifies due to technological progress and a growing demand for renewable energy,associated footprints on the seabed are becoming increasingly common within soft-bottom environments. A large part of the footprint is the scour protection, often consisting of rocks that are positioned on the seabed to prevent erosion. As such, scour protection may resemble a marine rocky reef and could have important ecosystem functions. While acknowledging that OWFs disrupt the marine environment, the aim of this systematic review was to examine the effects of scour protection on fish assemblages, relate them to the effects of designated artificial reefs (ARs) and, ultimately, reveal how future scour protection may be tailored to support abundance and diversity of marine species. The results revealed frequent increases in abundances of species associated with hard substrata after the establishment of artificial structures (i.e., both OWFs and ARs) in the marine environment. -

Guide to Fishing and Diving New Jersey Reefs

A GUIDE TO THIRD EDITION FISHING AND DIVING NEW JERSEY REEFS Revised and Updated DGPS charts of NJ’s 17 reef network sites, including 3 new sites Over 4,000 patch reefs deployed A GUIDE TO FISHING AND DIVING NEW JERSEY REEFS Prepared by: Jennifer Resciniti Chris Handel Chris FitzSimmons Hugh Carberry Edited by: Stacey Reap New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of Fish and Wildlife Bureau of Marine Fisheries Reef Program Third Edition: Revised and Updated Cover Photos: Top: Sinking of Joan LaRie III on the Axel Carlson Reef. Lower left: Deploying a prefabricated reef ball. Lower right: Bill Figley (Ret. NJ Reef Coordinator) holding a black sea bass. Acknowledgements The accomplishments of New Jersey's Reef Program over the past 25 years would not have been possible with out the cooperative efforts of many government agencies, companies, organizations, and a countless number of individuals. Their contributions to the program have included financial and material donations and a variety of services and information. Many sponsors are listed in the Reef Coordinate section of this book. The success of the state-run program is in large part due to their contributions. New Jersey Reef Program Administration State of New Jersey Jon S. Corzine, Governor Department of Environmental Protection Mark N. Mauriello, Acting Commissioner John S. Watson, Deputy Commissioner Amy S. Cradic, Assistant Commissioner Division of Fish and Wildlife David Chanda, Director Thomas McCloy, Marine Fisheries Administrator Brandon Muffley, Chief, Marine Fisheries Hugh Carberry, Reef Program Coordinator Participating Agencies The following agencies have worked together to make New Jersey's Reef Program a success: FEDERAL COUNTY U.S. -

Shipwrecks As Reefs: Biological Surveys

Education Shipwrecks as Reefs: Biological Surveys Grade Level • Grade 6 – 8 Timeframe • 45 – 90 minutes Materials • 20ft Measured rope or measuring tape (x2) Activity Summary • Cut-outs of fish species and The focus of this lesson is to highlight the use of shipwrecks as artificial reefs. benthic species Students will conduct a mock biological survey of fish populations using • 2ft x 2ft square frames (e.g. practiced methods of visual census transects and stationary quadrats. Students rulers taped together) will apply and practice data sampling, collection, and analysis techniques. • Clipboards Students will make observations of similarities and differences between surveys • Student sheets and then make informed conclusions based on the data. Key Words Learning Objectives • Artificial Reef Students will be able to: • Biological Survey • Define artificial reefs and describe their environmental and economic impact • Transect Line • Demonstrate data sampling and collection techniques • Quadrat • Illustrate graphical representations of data • Biodiversity • Compare surveys based on similar and different factors, determining the effects of the factors on population and diversity http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/education Vocabulary QUADRAT – reference square that defines a sample area; BIOLOGICAL SURVEY – observation and data collection of used for less mobile/stationary species organic populations BIODIVERSITY – diversity of organic life within an TRANSECT LINE – reference line that runs the length of a environment sample area ARTIFICIAL REEF – a reef that has developed on a man- BENTHIC – collection of organisms living on the bottom of made object, such as a shipwreck lake, river, or ocean Background Information • Cut out the pictures of Fish Species and During World War II, many battles were fought on Benthic Species foreign shores. -

1 Strategic Environmental Assessment

Strategic Environmental Assessment - SEA5 Technical Report for Department of Trade & Industry NORTHERN NORTH SEA SHELLFISH AND FISHERIES Prepared by: Colin J Chapman Bloomfield Milltimber Aberdeenshire AB13 0EQ 1 NORTHERN NORTH SEA SHELLFISH AND FISHERIES Prepared by: Colin J Chapman Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................... 10 2. Shellfish resources..................................................................................... 10 2.1 Fishery data ........................................................................................ 10 2.2 Crustacean species 2.2.1 Norway lobster, Nephrops norvegicus (L.).............................. 11 2.2.2 European lobster, Homarus gammarus (L.)............................. 16 2.2.3 Edible crab, Cancer pagurus (L.)............................................. 20 2.2.4 Velvet swimming crab, Necora puber (L.) .............................. 23 2.2.5 Shore crab, Carcinus maenus (L.)............................................ 25 2.2.6 Pink shrimp, Pandalus borealis Kroyer................................... 26 2.2.7 Other species ............................................................................ 28 2.3 Bivalve molluscs 2.3.1 Scallop, Pecten maximus (L.)................................................... 29 2.3.2 Queen scallop, Aequipecten opercularis (L.)........................... 32 2.3.3 Cockle, -

View Enlarged Reef

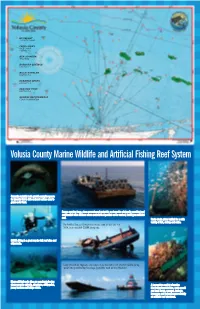

ED KELLEY COUNTY CHAIR FRED LOWRY VICE-CHAIR DISTRICT 5 BEN JOHNSON AT-LARGE BARBARA GIRTMAN DISTRICT 1 BILLIE WHEELER DISTRICT 2 DEBORAH DENYS DISTRICT 3 HEATHER POST DISTRICT 4 GEORGE RECKTENWALD COUNTY MANAGER Volusia County Marine Wildlife and Artificial Fishing Reef System Concrete material reefs provide complex spaces for juvenile sh to hide and reef surface area to graze on for food. Barges carrying large, clean concrete reef materials are towed to a federally permitted reef construction sites offshore where material is deposited on the seabed, forming an articial reef. Reefs create prime habitat for a wide variety of sh, shrimp and crabs. The Antilles Star, a 165-foot steel vessel sunk at Reef Site 4 in 2004, is an excellent SCUBA diving site. SCUBA diving is a great way to visit reef sites and shipwrecks. Large steel ships, tugboats and barges make wonderful reef sites for SCUBA diving, spearshing and trolling for pelagic gamesh, such as King Mackerel. Many articial reefs sites are constructed using clean concrete culverts, structures, utility poles, A tremendous variety of marine jersey barriers and bridge rubble. bio-fouling invertebrates, such as soft and hard corals, sponges, tunicate, bryozoans and barnacles grow directly on articial reef structures. Many species of remarkable marine tropical fish inhabit the artificial reef sites. Volusia County Marine Wildlife Habitat and Artificial Fishing Reef Site Coordinates Volusia County currently maintains 15 federally permitted marine habitat and artificial reef construction areas located on the continental shelf offshore Ponce de Leon Inlet. Reef habitat construction areas 1 through 13 are 5,000ft x 5,000ft square with multiple reef habitat sites located within and spaced approximately 300ft to 500ft apart. -

Coral Reef Restoration

CORAL REEF RESTORATION AS A STRATEGY TO IMPROVE ECOSYSTEM SERVICES A guide to coral restoration methods Copyright Suggested Citation Additional Support © 2020 United Nations Hein MY1,2, McLeod IM2, Shaver EC3, This project was also supported by Environment Programme Vardi T4, Pioch S5, Boström-Einarsson the Australian Government’s National L2,6, Ahmed M7, Grimsditch G7(2020) Environmental Science Program This publication may be reproduced Coral Reef Restoration as a strategy Tropical Water Quality Hub (NESP in whole or in part and in any form for to improve ecosystem services – TWQ) funding to Ian McLeod, Margaux educational or non-profit services A guide to coral restoration methods. Hein, and Lisa Boström-Einarsson. without special permission from United Nations Environment Program, the copyright holder, provided Nairobi, Kenya. Acknowledgement acknowledgement of the source is made. United Nations Environment 1 Marine Ecosystem Restoration (MER) We would like to express our gratitude Programme would appreciate receiving Research and Consulting, Monaco to the following experts for supporting this report through the provision of a copy of any publication that uses this 2 TropWATER, James Cook University, publication as a source. text, case studies, photos, external peer Australia review and guidance: Amanda Brigdale, No use of this publication may be made 3 The Nature Conservancy, USA Anastazia Banaszak, Agnes LePort, for resale or any other commercial Tory Chase, Tom Moore, Tadashi 4 ECS for NOAA Fisheries, USA purpose whatsoever without prior Kimura, members of the ICRI Ad-Hoc permission in writing from the United 5 University Montpellier 3 Paul Valery, Committee on coral reef restoration, Nations Environment Programme. -

Book Layout.Indd

CONTENTS Executive Summary v Chapter 1 1-1 Introduction Chapter 2 2-1 The Ecological Role of Oil and Gas Production Platforms and Natural Outcrops on Fishes in A Brief History of Oil Development in Southern California Southern and Central California: A Synthesis of Information Chapter 3 3-1 A Review of Biological and Oceanographic Surveys: Results and Analyses OCS Study MMS 2003-032 Disclaimer Chapter 4 4-1 This research was conducted under a cooperative agree- A Guide to Ecological and Political Issues Surrounding Oil Platform Decommissioning in California Milton S. Love ment (Agreement 1445-CA09-95-0836) between the U. S. Chapter 5 5-1 Donna M. Schroeder Geological Survey (Biological Resources Division) and the Research and Monitoring Recommendations Mary M. Nishimoto University of California, Santa Barbara. This report was re- viewed and approved for publication by the BRD. Approval Acknowledgements and Personal Communications 5-3 Marine Science Institute does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views References R-1 University of California and policies of the BRD or MMS, nor does mention of trade Tables T-1 Santa Barbara, CA, 93106 names or commercial products constitute endorsement or Appendices email address (for M. Love): [email protected] recommendation for use. www.id.ucsb.edu/lovelab Appendix 1 A-1 Report Availability Appendix 2 A-11 June 2003 Available for viewing and in PDF at: www.id.ucsb.edu/lovelab Appendix 3 A-13 Prepared under Cooperative Agreement #1445-CA09- Appendix 4 A-29 95-0836 between the Biological Resources Division, U. S. Reprints available at: Geological Survey, and the Marine Science Institute, Uni- Milton Love versity of California, Santa Barbara, in cooperation with Marine Science Institute the Minerals Management Service, Pacific OCS Region.