St. Patrick's College Maynooth the PROSPECTS of INTERFAITH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contenidos #71: 7 Al 25 De Abril De 2014

DIRECTORIO Contenidos #71: 7 al 25 de abril de 2014 DIRECCIÓN ESPECIAL: CANONIZACIÓN DE JUAN XXIII Y JUAN PABLO II .......................... 5 Observatorio Eclesial 1. Juan XXIII y Juan Pablo II: canonización de dos modelos de iglesia irreconciliables ... 5 2. Canonizaciones 2014: un abordaje no católico: Leopoldo Cervantes-Ortiz ................ 6 3. Canonización de Juan Pablo II prevista para este mes aún encuentra resistencias .... 9 CONSEJO EDITORIAL 4. Pide el Observatorio Eclesial al Papa detener la canonización de Wojtyla ............... 10 Gabriela Juárez Palacios 5. Navarro Valls asegura que JPII "fue informado" del proceso contra Maciel ............. 10 Marisa Noriega 6. África rinde homenaje a Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII .................................................... 11 José Guadalupe Sánchez Suárez 7. Roma gastará 8 millones de euros en la canonización de Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII . 13 8. El cardenal Martini cuestionó la canonización de Juan Pablo II ................................ 13 9. Papa Francisco hará Santo a un cómplice de pederastas, Athié ............................... 14 DISTRIBUCIÓN 10. Los santos, intercesores en boga en la Iglesia Católica ............................................. 15 Observatorio Eclesial 11. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 15 http://observatorioeclesial.wordpress.com 12. Marcial Maciel, ¿la 'piedra en el zapato' para canonizar a Juan Pablo II? ................. 16 13. Piden replantear canonización de Juan Pablo II pues sí supo de Maciel ................... 18 SUSCRIPCIONES 14. Juan Pablo II conocía la investigación del Vaticano contra Maciel: exportavoz ........ 18 [email protected] 15. Juan XXIII, ¡más que simple beato! ............................................................................ 19 16. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 22 Alas es un boletín semanal que recopila la información hemerográfica 17. -

POPE Benedict XVI's Resignation Has Sparked Calls For

[POPE Benedict XVI's resignation has sparked calls for his successor to come from Africa, home to the world's fastest-growing population and the front line of key issues facing the Roman Catholic Church. Around 15 per cent of the world's 1. 2 billion Catholics live in Africa and the per centage has expanded significantly in recent years in comparison to other parts of the world. Much of the Catholic Church's recent growth has come in the developing world, with the most rapid expansions in Africa and Southeast Asia. Names such as Ghana's Peter Turkson and Nigerian John Onaiyekan have been mentioned as potential papal material, as has Francis Arinze, also from Nigeria and considered a possibility when Benedict was elected, but who is now 80. ] BURUNDI : RWANDA : Protests in Rwanda Over Genocide Acquittals February 11, 2013 /(AP)/abcnews. go. com KIGALI, Rwanda Hundreds of Rwandans on Monday marched to the offices of the United Nations tribunal set up to try key cases related to Rwanda's 1994 genocide to protest the court's decision to acquit two former cabinet ministers accused of masterminding killings. The protesters, bearing placards denouncing the Arusha, Tanzania-based International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda (ICTR), mainly constituted of survivors of the genocide, youths and students who accused the tribunal of denying justice to genocide victims. "The international community failed in their response to protect the Tutsi from being killed and now it is failing to provide justice to survivors," one of the banners read. More than 500,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed during Rwanda's 1994 genocide. -

SPC FF USM Winter 2012 Page 1

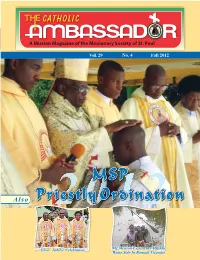

A Mission Magazine of the Missionary Society of St. Paul Vol.l 29 No. 4 Fall 2012 St. Francis Intercede for Peace in Nigeria and the World 2 VOL. 29 NO. 4 THE CATHOLIC AMBASSADOR Message from the Acting Superior Very Rev. Fr Paul Ofoha, MSP henever I think of an expression the unknown is appropriate, but it can be to qualify the current wave of transformed by faith when we turn to God. W insecurity in Nigeria and in other parts of the world, I always recall Psalm These experiences could lead to despair but if 28.8: “The Lord is the strength of his people”. true Christian spirit is applied and the events Despite all the bomb attacks and incidences of offered to God with all sense of rectitude, it kidnapping which have caused insecurity and could result in humility and a deeper fear, God is always with us, our refuge and gratitude for God's love. In our powerlessness strength. We do not pretend to "demonstrate" we can best experience God's love for us, and God's existence in the midst of insecurity; we our need for God's ready embrace. Let us simply try to find out where God is in all these reflect on our attitude towards God in those are conquerors because of him that loved us” troubles. This is because with faith and trust in difficult and frustrating moments of our lives. (Rom 8:35,37) exhorts St Paul. He further God, we can surmount all our present fears. For this is the time for Christians to bear affirms, “For I am sure, that neither death, nor witness in faith and hope that God still exists life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor If we remain faithful to our Lord in time of and that He is still there for us. -

Senate Committee Report

THE 7TH SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION REPORT OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION ON A BILL FOR AN ACT TO FURTHER ALTER THE PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 1999 AND FOR OTHER MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH, 2013 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria referred the following Constitution alterations bills to the Committee for further legislative action after the debate on their general principles and second reading passage: 1. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.107), Second Reading – Wednesday 14th March, 2012 2. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.136), Second Reading – Thursday, 14th October, 2012 3. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.139), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 4. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.158), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 5. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.162), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 6. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.168), Second Reading – Thursday 1 | P a g e 4th October, 2012 7. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.226), Second Reading – 20th February, 2013 8. Ministerial (Nominees Bill), 2013 (SB.108), Second Reading – Wednesday, 13th March, 2013 1.1 MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Sen. Ike Ekweremadu - Chairman 2. Sen. Victor Ndoma-Egba - Member 3. Sen. Bello Hayatu Gwarzo - “ 4. Sen. Uche Chukwumerije - “ 5. Sen. Abdul Ahmed Ningi - “ 6. Sen. Solomon Ganiyu - “ 7. Sen. George Akume - “ 8. Sen. Abu Ibrahim - “ 9. Sen. Ahmed Rufa’i Sani - “ 10. Sen. Ayoola H. Agboola - “ 11. Sen. Umaru Dahiru - “ 12. Sen. James E. -

Event Report | June 18, 2013 Prepared by Continental Project Affairs Associates (Cpaa)

EVENT REPORT | JUNE 18, 2013 PREPARED BY CONTINENTAL PROJECT AFFAIRS ASSOCIATES (CPAA) Theme: ‘‘Internet Governance for Empowerment, National Integration, and Security through Multi-stakeholders’ Engagement’’ Goal: Harmonization of National Multi-Stakeholders Positions based on the Global IGF framework covering: Digital Inclusion and Integration; Building Trust, Confidence, & Assurance on the Internet; Policy and Regulatory Model for the Internet; Encouraging Local Research on Internet Development in Nigeria; Addressing Infrastructural Challenges in the Cashless Society; and Emerging IssuesOrganizers and Way: Forward ~ 1 ~ NIGF 2013 REPORT CERTIFICATION We hereby certify that the 2013 edition of Nigeria Internet Governance Forum organized by Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), National Information, Technology Development Agency (NITDA), Nigerian Internet Registration Association (NiRA) in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Communication Technology did take place at the Shehu Musa Yar’adua Centre Abuja on the June 18, 2013. The report of the NIGF 2013 as captured in this document to the best of our knowledge, presents the actual proceedings, observations, delegate areas of concerns, and suggestions which are harmonized in the final work on the communiqué. To the best of our knowledge, the NIGF 2013 was a successful event with a record number of over Six Hundred delegates, 100 percent above the official 300 delegates participation forecast, 100 percent above the NIGF 2012 delegates population, with broader spectrum of internet -

Roman Catholic Leadership And/In Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I

Roman Catholic Leadership and/in Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International II. History of Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace Global Movement III. Milestones in the RfP - Vatican/Holy See Joint Journeys IV. Regional Spotlights - Common Purpose and Engagement between RfP mission and Catholic Leadership I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International WORLD COUNCIL H.E. Cardinal Charles Bo, Archbishop of Yangon, Myanmar; President, Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conference H.E. Cardinal Blasé J. Cupich, Archbishop of Chicago, United States H.E. Cardinal Dieudonné Nzapalainga, Archbishop of Bangui, Central African Republic H.E. Philippe Cardinal Ouédraogo, Archbishop of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; President, Symposium of African and Madagascar Bishops’ Conference (SECAM) H.E. Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples Ms. Maria Lia Zervino, President General, World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations, Argentina HONORARY PRESIDENTS H.E. Cardinal John Onaiyekan, Archbishop Emeritus of Abuja, Nigeria; Co-Chair, African Council of Religious Leaders-RfP H.E. Cardinal Vinko Puljić, Archbishop of Vrhbosna, Bosnia-Herzegovina Emmaus Maria Voce, President, Movimento Dei Focolari, Italy 777 United Nations Plaza | New York, NY 10017 USA | Tel: 212 687-2163 | www.rfp.org 1 | P a g e LEADERSHIP H.E. Cardinal Raymundo Damasceno Assis, Archbishop Emeritus of Aparecida, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Moderator, Religions for Peace-Latin America and Caribbean Council of Religious Leaders Rev. Sr. Agatha Ogochukwu Chikelue, Nun of the Daughters of Mary Mother of Mercy; Co- Chair Nigerian & African Women of Faith Network; Executive Director Cardinal Onaiyekan Foundation for Peace (COFP) II. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Conference Booklet

Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development Peace 2-3 February 2017 | Casina Pio IV | Vatican City Peacebuilding through active nonviolence is the natural and necessary complement to the Church’s continuing efforts to limit the use of force by the application of moral norms; she does so by her participation in the work of international “ institutions and through the competent contribution made by so many Christians to the drafting of legislation at all levels. Jesus himself offers a “manual” for this strategy of peacemaking in the Sermon on the Mount. The eight Beatitudes (cf. Mt 5:3-10) provide a portrait of the person we could describe as blessed, good and authentic. Blessed are the meek, Jesus tells us, the merciful and the peacemakers, those who are pure in heart, and those who hunger and thirst for justice. Nonviolence: a Style of Politics for Peace, Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for the Celebration of the Fiftieth World Day of Peace, 1 January” 2017 2 Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development | Peace The Importance of Peace he purpose of this meeting is to answer the other technological advances. And the socio-cultural question posed by Pope Benedict XVI to the landscape is being reshaped by an explosive growth in T representatives of the world’s religions gathered information and communications technology, and by in Assisi to pray for peace: “What is the state of peace the revolution in social norms and morals that define today?” Accordingly, Ethics in Action will reflect on how an individualistic society rooted in the technocratic to achieve the tranquillitas ordinis (the tranquility of paradigm, at the expense of notions such as virtue, the order), as Saint Augustine denoted peace (De Civitate common good, and social justice. -

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

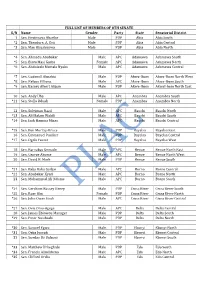

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

Face up to Anti-Catholicism

No 5495 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLICwww.sconews.co.uk NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday November 30 2012 | £1 SCIAF FUNDING BOOST CELEBRATING ST ANDREW’S DAY WITH A SMILE OR TWO MALAWI PROJECTS run by the charity receive nearly £500,000 from the Scottish Government Page 7 Archbishop Philip Tartaglia of Glasgow joined staff and pupils of the city’s St Andrew’s Secondary School on Monday to celebrate a feast day Mass for the school’s patron saint. In anticipation of the feast day, today, Gerry Lyons, St Andrew’s headteacher, and the school community were delighted to welcome Archbishop Tartaglia and priests of the archdiocese —including Fr Joseph Sullivan, school chaplain and a former pupil at the school, and Fr Mark Morris, also a former pupil—for the celebrations. The archbishop, making his first visit to a Glasgow secondary school since his inauguration in September, blessed St Andrew’s new oratory and also launched the school’s charities’ campaign PIC: PAUL McSHERRY Face up to anti-Catholicism ST ANDREW’S CONFERENCE IArchbishop Tartaglia says the Scottish Government must endeavour to tackle the problem By Ian Dunn Catholic community of Scotland “I think the vast majority of clergy remains steadfast in faith, joyful in and laity in this country have developed ARCHBISHOP Philip Tartaglia of hope and fully committed to being part very thick skins,” he said. “The vast Glasgow has said that the Scottish of Scottish society.” majority of crimes against Catholics are Government is refusing to face up never reported.” to the brutal nature of anti-Catholi- Failing Catholics cism in Scotland, as new Crown Peter Kearney, director of the Scottish Problem worsening Office statistics show an increase in Catholic Media Office, said the rise in Dave Scott of the charity Nil by Mouth attacks on Catholics. -

Contemporary Challenges for Vatican II's Theology of the Laity

Contemporary Challenges for Vatican II’s Theology of the Laity: The Nigerian Church Experience by Francis C. Ezenezi A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Regis College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College © Copyright by Francis C. Ezenezi 2015 Contemporary Challenges for Vatican II’s Theology of the Laity: The Nigerian Church Experience Francis C. Ezenezi Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2015 Abstract Vatican II stipulates that the laity by virtue of their baptism are constitutive members of the Church and should play their role in the mission of the whole Christian faithful in the Church and the world. More than fifty years since the beginning of the Council, the Church in Nigeria is still struggling to understand itself as well as to discern the identity, the role and participation of the lay Christian faithful in the mission of the Church. This thesis explores and analyzes the strengths and limitations of the current dominant ecclesiology of the Roman Catholic Church in Nigeria, and constructively suggests various means of overcoming some of these deficiencies. It will proffer and argue that the contemporary challenges which Vatican II’s theology of the laity faces today in the Nigerian Roman Catholic Church call for a Church that is not only participatory, but also prophetic as well as a Church that engages and is constantly in solidarity with the people of God. -

Lessons from Nigeria's 2011 Elections

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°81 Abuja/Dakar/Brussels, 15 September 2011 Lessons from Nigeria’s 2011 Elections democracy and overall political health. The eve of the elec- I. OVERVIEW tions was marked by a blend of cautious optimism and foreboding. Attahiru Jega, INEC chair, and his team won With the April 2011 general elections, Nigeria may have plaudits for instituting important reforms, including to the taken steps towards reversing the degeneration of its pre- voting procedure; the introduction of the idea of commu- vious elections, but the work is not finished. Despite some nity mandate protection to prevent malpractice; and the progress, early and intensive preparations for the 2015 prosecution and sentencing of officials, including the elections need to start now. Voter registration need not be electoral body’s own staff, for electoral offences. There as chaotic and expensive as it was this year if done on a were also grounds for pessimism: the upsurge of violence continual basis. Far-reaching technical and administrative in several states, encouraged by politicians and their sup- reforms of, and by, the Independent National Electoral porters who feared defeat; an ambiguous and confusing Commission (INEC), notably internal restructuring and legal framework for the elections; and a flawed voter reg- constituency delineation, should be undertaken and ac- istration exercise, with poorly functioning biometric scans, companied by broad political and economic reforms that that resulted in an inflated voters roll. make the state more relevant to citizens and help guaran- tee an electoral and democratic future. The deadly post- Few, however, predicted the violence that erupted in some presidential election violence in the North and bomb blasts Northern states following the announcement of the presi- by the Islamic fundamentalist Boko Haram sect since dential results.