Contemporary Challenges for Vatican II's Theology of the Laity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contenidos #71: 7 Al 25 De Abril De 2014

DIRECTORIO Contenidos #71: 7 al 25 de abril de 2014 DIRECCIÓN ESPECIAL: CANONIZACIÓN DE JUAN XXIII Y JUAN PABLO II .......................... 5 Observatorio Eclesial 1. Juan XXIII y Juan Pablo II: canonización de dos modelos de iglesia irreconciliables ... 5 2. Canonizaciones 2014: un abordaje no católico: Leopoldo Cervantes-Ortiz ................ 6 3. Canonización de Juan Pablo II prevista para este mes aún encuentra resistencias .... 9 CONSEJO EDITORIAL 4. Pide el Observatorio Eclesial al Papa detener la canonización de Wojtyla ............... 10 Gabriela Juárez Palacios 5. Navarro Valls asegura que JPII "fue informado" del proceso contra Maciel ............. 10 Marisa Noriega 6. África rinde homenaje a Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII .................................................... 11 José Guadalupe Sánchez Suárez 7. Roma gastará 8 millones de euros en la canonización de Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII . 13 8. El cardenal Martini cuestionó la canonización de Juan Pablo II ................................ 13 9. Papa Francisco hará Santo a un cómplice de pederastas, Athié ............................... 14 DISTRIBUCIÓN 10. Los santos, intercesores en boga en la Iglesia Católica ............................................. 15 Observatorio Eclesial 11. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 15 http://observatorioeclesial.wordpress.com 12. Marcial Maciel, ¿la 'piedra en el zapato' para canonizar a Juan Pablo II? ................. 16 13. Piden replantear canonización de Juan Pablo II pues sí supo de Maciel ................... 18 SUSCRIPCIONES 14. Juan Pablo II conocía la investigación del Vaticano contra Maciel: exportavoz ........ 18 [email protected] 15. Juan XXIII, ¡más que simple beato! ............................................................................ 19 16. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 22 Alas es un boletín semanal que recopila la información hemerográfica 17. -

The Development of Sacrosanctum Concilium Part 2 Or, How to Grok

The development of Sacrosanctum Concilium Part 2 - a presentation by Seán O’Seasnáin on becoming familiar with Vatican II and the Liturgy with a focus on Chapter 4 of What Happened at Vatican II by John W. O’Malley The Lines Are Drawn - The First Period (1962) or, How to grok Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) while avoiding moonbats and wingnuts from the vantage point of a young Irish friar in formation at the time of Vatican II The four aggiornamento modernization principles identified by John W. O’Malley p140f 1) ressourcement 2) adaptation 3) episcopal collegiality and 4) active participation (Ch.4 of What Happened at Vatican II) are correctly described by O’Malley as fundamental and traditional principles. In a harsh and pedantic review of What Happened at Vatican II the late Richard John Neuhaus, on one hand gives O’Malley back-handed compliments for his balanced analysis, and in the next sentence rushes in to castigate him with misleading accusations of presenting the ‘discontinuity’ perspective of the council. Neuhaus writes dismissively: “What Happened at Vatican II is a 372-page brief for the party of novelty and discontinuity. Its author comes very close to saying explicitly what is frequently implied: that the innovationists practiced subterfuge, and they got away with it” [10]. I would have to credit Neuhaus with providing a reminder here of how appropriate the ‘moonbat’ and ‘wingnut’ designations are when it comes to critiques of Vatican II and the liturgy. He writes: “In the decades following the council, many liberals made no secret of their belief that aggiornamento was a mandate for radical change, even revolution. -

Individual Confession Bishops Asked to Avoid Abuses of Generai Absolution by Agostino Bono VATICAN CITY (NC) - Pope John Paul II Has Told U.S

The Denver Catholfc R j^tster JUNE 8, 1988 VOL. LXIV NO. 23 Colorado’s Largest Weekly 28 PAGES 25 CENTS Individual Confession Bishops asked to avoid abuses of generai absolution By Agostino Bono VATICAN CITY (NC) - Pope John Paul II has told U.S. bishops to promote greater individual Confession and to avoid abuses of general absolution. The sacrament of Penance is in crisis in many parts of the world because of “unwarranted interpretations’’ of the requirements for general absolution, he told a group of U.S. bishops May 31. The renewal process envisioned by the Second Vati can Council requires “the practice of integral and individual Confession of sins,’’ he added. The Pope said national bishops’ conferences must continuously promote better understanding of the re quirements for general absolution contained in canon law, the church’s legal code. “Sporadic efforts are not enough to overcome the crisis,’’ he said. Not criticizing U.S. One U.S. bishop who attended the papal meeting said the Pope was not criticizing U.S. practices but reiterating general principles. “I welcomed it," said Archbishop Thomas C. Kelly of Louisville, Ky. “It was encouragement to foster the sacrament of Penance.” The Pope spoke to 20 bishops from Louisiana, Ken tucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama and the Archdiocese for the Military Services. They were at the Vatican for their “ad limina ” Photo by Mark Beede visits, required of diocesan heads every five years to Charity Chase report on the status of their dioceses. General absolution takes place when a priest grants Proper tension on a sweatband is important or than 2,350 runners traversed the three-plus-mlle absolution from sin to a number of people at the same runners might iose their concentration. -

"Catholic Church, Where Are You Going?" a Conference. That It Not Lose Its Way

"Catholic Church, Where Are You Going?" A Conference. That It Not Lose Its Way Dm, 20/03/2018 URL article: http://magister.blogautore.espresso.repubblica.it/2018/03/20/catholic-church-whe … > Italiano > English > Español > Français > All the articles of Settimo Cielo in English * It is confirmed. Next April 7, the Saturday of Easter Week, a very special conference will be held in Rome. The intention of which will be to show the Catholic Church the way to go, after the uncertain journey of the first five years of the pontificate of Pope Francis. The reckoning of this five-year period, in fact, is rather critical, to judge from the title of the conference: “Catholic Church, where are you going?” And even more so if one looks at the subtitle: “Only a blind man can deny that in the Church there is great confusion.” This is taken from a statement of Cardinal Carlo Caffarra (1938-2017), not forgotten as an endorser, together with other cardinals, of those “dubia” submitted in 2016 to Pope Francis for the purpose of bringing clarity on the most controversial points of his magisterium, but which he has left without a response. In a Church seen as being set adrift, the key question that the conference will confront will be precisely that of redefining the leadership roles of the “people of God,” the characteristics and limitations of the authority of the pope and the bishops, the forms of consultation of the faithful in matters of doctrine. 1 These are questions that were thoroughly explored, in his time, by a great cardinal who is often cited both by progressives and by conservatives in support of their respective theses, Blessed John Henry Newman. -

POPE Benedict XVI's Resignation Has Sparked Calls For

[POPE Benedict XVI's resignation has sparked calls for his successor to come from Africa, home to the world's fastest-growing population and the front line of key issues facing the Roman Catholic Church. Around 15 per cent of the world's 1. 2 billion Catholics live in Africa and the per centage has expanded significantly in recent years in comparison to other parts of the world. Much of the Catholic Church's recent growth has come in the developing world, with the most rapid expansions in Africa and Southeast Asia. Names such as Ghana's Peter Turkson and Nigerian John Onaiyekan have been mentioned as potential papal material, as has Francis Arinze, also from Nigeria and considered a possibility when Benedict was elected, but who is now 80. ] BURUNDI : RWANDA : Protests in Rwanda Over Genocide Acquittals February 11, 2013 /(AP)/abcnews. go. com KIGALI, Rwanda Hundreds of Rwandans on Monday marched to the offices of the United Nations tribunal set up to try key cases related to Rwanda's 1994 genocide to protest the court's decision to acquit two former cabinet ministers accused of masterminding killings. The protesters, bearing placards denouncing the Arusha, Tanzania-based International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda (ICTR), mainly constituted of survivors of the genocide, youths and students who accused the tribunal of denying justice to genocide victims. "The international community failed in their response to protect the Tutsi from being killed and now it is failing to provide justice to survivors," one of the banners read. More than 500,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed during Rwanda's 1994 genocide. -

SPC FF USM Winter 2012 Page 1

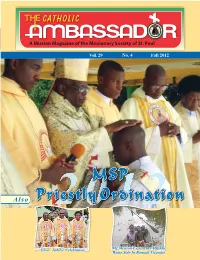

A Mission Magazine of the Missionary Society of St. Paul Vol.l 29 No. 4 Fall 2012 St. Francis Intercede for Peace in Nigeria and the World 2 VOL. 29 NO. 4 THE CATHOLIC AMBASSADOR Message from the Acting Superior Very Rev. Fr Paul Ofoha, MSP henever I think of an expression the unknown is appropriate, but it can be to qualify the current wave of transformed by faith when we turn to God. W insecurity in Nigeria and in other parts of the world, I always recall Psalm These experiences could lead to despair but if 28.8: “The Lord is the strength of his people”. true Christian spirit is applied and the events Despite all the bomb attacks and incidences of offered to God with all sense of rectitude, it kidnapping which have caused insecurity and could result in humility and a deeper fear, God is always with us, our refuge and gratitude for God's love. In our powerlessness strength. We do not pretend to "demonstrate" we can best experience God's love for us, and God's existence in the midst of insecurity; we our need for God's ready embrace. Let us simply try to find out where God is in all these reflect on our attitude towards God in those are conquerors because of him that loved us” troubles. This is because with faith and trust in difficult and frustrating moments of our lives. (Rom 8:35,37) exhorts St Paul. He further God, we can surmount all our present fears. For this is the time for Christians to bear affirms, “For I am sure, that neither death, nor witness in faith and hope that God still exists life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor If we remain faithful to our Lord in time of and that He is still there for us. -

The Virtue of Penance in the United States, 1955-1975

THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Maria Christina Morrow UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2013 THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Chair _______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member Mary Ann Spearin Chair in Catholic Theology _______________________________________ Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ Jana M. Bennett, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________________ William C. Mattison, III, Ph.D. Committee Member iii ABSTRACT THE VIRTUE OF PENANCE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1955-1975 Name: Morrow, Maria Christina University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation examines the conception of sin and the practice of penance among Catholics in the United States from 1955 to 1975. It begins with a brief historical account of sin and penance in Christian history, indicating the long tradition of performing penitential acts in response to the identification of one’s self as a sinner. The dissertation then considers the Thomistic account of sin and the response of penance, which is understood both as a sacrament (which destroys the sin) and as a virtue (the acts of which constitute the matter of the sacrament but also extend to include non-sacramental acts). This serves to provide a framework for understanding the way Catholics in the United States identified sin and sought to amend for it by use of the sacrament of penance as well as non-sacramental penitential acts of the virtue of penance. -

YVES CONGAR's THEOLOGY of LAITY and MINISTRIES and ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION in the UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to Th

YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Alan D. Mostrom UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2018 YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Timothy R. Gabrielli, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader, Seton Hill University ___________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Alan D. Mostrom All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. Yves Congar’s theology of the laity and ministries is unified on the basis of his adaptation of Christ’s triplex munera to the laity and his specification of ministry as one aspect of the laity’s participation in Christ’s triplex munera. The seminal insight of Congar’s adaptation of the triplex munera is illumined by situating his work within his historical and ecclesiological context. The U.S. reception of Congar’s work on the laity and ministries, however, evinces that Congar’s principle insight has received a mixed reception by Catholic theologians in the United States due to their own historical context as well as their specific constructive theological concerns over the laity’s secularity, or the priority given to lay ministry over the notion of a laity. -

Medina County Woman Hopes Cold Murder Case Will Heat Up

DAILY NZ P A G E 1A C O L O R P U B D A T E 04-10-05 O P E R A T O R SBLACKWELL DATE / / TIME : State Edition www.MySanAntonio.com THE VOICE OF SOUTH TEXAS SINCE 1865 $1.50 ROYALS HITCHED WITHOUT A HITCH Medina County woman hopes fter 33 star-crossed cold murder case will heat up Aand often unhappy years, Bexar sheriff’s unit now green binder that holds her fon- Christina Hasler, 8, were found dest memories and worst night- dead in their mobile home in through other looking into deaths. mares. Southwest Bexar County five years marriages, public D She began typing: ago on March 28. March 18 “MARCH 2005, the fifth year an- would’ve been Christina’s 13th scorn and familial BY MARIANO CASTILLO niversary of my kids’ deaths. The birthday. dismay, Britain’s EXPRESS-NEWS STAFF WRITER pain gets worse as time passes, The pair were beaten and Nea- you feel so very desperate. WHAT gley stabbed, and both had been Prince Charles and Past sundown, in an isolated CAN I DO TO FIND THIS MUR- dead for several days before they the Duchess of house atop a hill in northeastern DERER? Does no one care?” were discovered in their home Medina County, Anna Jean Hasler The page would go inside the near the Medina County line. Cornwall — the pulled her wheelchair up to the binder, a collection of photos and The investigation garnered more former Camilla kitchen table and placed her fin- writings that chronicle the lives attention in Medina County than gertips on the keys of an electric and unsolved double homicide of in Bexar, and after a year and a TOBY MELVILLE/ASSOCIATED PRESS Parker Bowles — typewriter. -

PRESENTATION of the COMMUNIQUÉS of the GENERAL CHAPTER 1. from January

[Translated from Original Spanish] Thy Kingdom Come! PRESENTATION OF THE COMMUNIQUÉS OF THE GENERAL CHAPTER 1. From January 8th through February 25th, 2014, the Extraordinary General Chapter of the Legion of Christ took place in Rome. His Eminence, Cardinal Velasio De Paolis, CS, and his two counselors, Fr. Gianfranco Ghirlanda, SJ, and Fr. Agostino Montan, CSI, presided. Sixty- one chapter fathers participated, 19 ex officio and 42 elected by the nine territories of the congregation and the centers of Rome. 2. This Extraordinary General Chapter marks the end of the journey of in-depth revision that the congregation has travelled since the apostolic visitation, which took place during 2009- 2010, and the naming of a Pontifical Delegate in the summer of 2010. Our principal tasks in the Chapter, as Pope Benedict XVI1 indicated and as Pope Francis confirmed2, were to revise the Constitutions and to elect a new central government for the congregation. 3. In the first days, in light of the reports that the Pontifical Delegate and the pro-General Director submitted, we focused on analyzing the life of the Congregation since the ordinary General Chapter that took place in 2005. One of the outcomes of the intense exchange of ideas that took place in those days was the communiqué that the Chapter approved on January 20th, 2014, about the journey of renewal of the Congregation. This same day, the elections of the new central government took place. Once the election had been confirmed and the Holy See made the two nominations that it had reserved to itself, the elections of Fr. -

Pope Says Pastors Must 'Serve, Not Use' Laypeople

Pope says pastors must ‘serve, not use’ laypeople By Cindy Wooden Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY – Clericalism is a danger to the Catholic Church not only because on a practical level it undermines the role of laity in society, but because theologically it “tends to diminish and undervalue the baptismal grace” of all believers, whether they are lay or clergy, Pope Francis said. “No one is baptized a priest or bishop,” the pope said in a letter to Cardinal Marc Ouellet, prefect of the Congregation for Bishops and president of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America. The fundamental consecration of all Christians occurs at baptism and is what unites all Christians in the call to holiness and witness. In the letter, released at the Vatican April 26, Pope Francis said he wanted to ensure that a discussion begun with members of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America March 4 “does not fall into a void.” The topic of the March discussion, he said, was on the public role of the laity in the life of the people of Latin America. In the letter, Pope Francis said that in lay Catholics’ work for the good of society and for justice, “it is not the pastor who must tell the layperson what to do and say, he already knows this and better than we do.” “It is illogical and even impossible to think that we, as pastors, should have a monopoly on the solutions for the multiple challenges that contemporary life presents,” he said. “On the contrary, we must stand alongside our people, accompany them in their search and stimulate their imagination in responding to current problems.” Pastors are not conceding anything to the laity by recognizing their role and potential in bringing the Gospel to the world; the laity are just as much members of “holy, faithful people of God” as the clergy, the pope said. -

St. Vincent De Paul Parish School

St.St. VincentVincent dede PaulPaul ParishParish WorshipWorship •• ServeServe •• GrowGrow SeptemberMarch 0905, , 20172018 Twenty-third Sunday1st in Sunday Ordinary of LentTime As Mass was ending last Sunday evening, the sun was reflecting the beauty of our stained glass window over our Easter candle. 30525 8th Avenue South, Federal Way, WA 98003 (253) 839-2320 www.stvincentparish.org Lay Ministry M Who are we? The responsibilities and rights of the laity to E participate in the work and mission of the Church Mission are based on Scripture and tradition, formulated in Church teachings – especially those from the S Inspired by the Holy Spirit Second Vatican Council. Decree on the and empowered by the Sacraments, Apostolate of the Laity, Apostolicam Actuositatem, S our diverse community and it has two central points: first, lay people are worships, serves and grows called to be saints; second, lay people are called A in the love and knowledge of Jesus. directly by Christ to take part in the apostolate, in the mission of the Church. The laity are called to Vision bring the Catholic Church's presence to areas that G would not respond to the institutional church. We are a growing Catholic community The laity can help evangelize in the world, lead the E united and passionate world to a state of grace, and carry out charity and in deepening and sharing social works. (And you thought the job of a priest our relationship with Jesus Christ was difficult!) Apostolicam Actuositatem calls on through justice, love, and compassion. the laity to serve active roles in their churches, F families, communities, nations, and in the world.