Britannia a Near Life-Size, Togate Bust from Chichester, West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Applications for Selsey Parish

Planning Applications for Selsey Parish – Weeks 23,24 & 25 Week 23 SY/20/01100/DOM Rossall 2 Chichester Way Selsey PO20 0PJ Rear single storey extension to square the rear of the building, to create a utility room to the rear of the kitchen https://publicaccess.chichester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=Q9LWGJERIR400 SY/20/01110/FUL Mr Paul Kiff Police House 27 Chichester Road Selsey PO20 0NB Demolition of existing vacant dwelling, attached office building and 2 no. blocks of 6 no. garages and the construction of 4 no. dwellings and 8 no. parking spaces https://publicaccess.chichester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=Q9NQDNERISK00 SY/20/01227/DOM Mr And Mrs S Bow 120 Gainsborough Drive Selsey Chichester West Sussex Two storey side and single storey rear extension https://publicaccess.chichester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=QAKIHUER0UX00 Week 24 SY/20/01212/DOM Mr And Mrs Turner 1 Orpen Place Selsey Chichester West Sussex Proposed conservatory to north elevation. https://publicaccess.chichester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=QADO1RER0SR00 SY/20/01243/PLD Mr Raymond Martin Gates At South East End Of Park Road Selsey West Sussex Proposed lawful development installation of traffic calming gate, less than 1m high and associated hinged support and closing posts. https://publicaccess.chichester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=QAMIU1ER0YN00 Week 25 SY/20/01213/LBC Mr Nicholas Rose West Street House 32 West Street Selsey PO20 9AB Remove front flint/stone/brick wall and replace with restored wall using existing and recycled materials. -

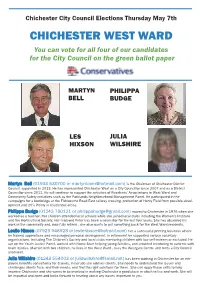

Chichester West Ward

Chichester City Council Elections Thursday May 7th CHICHESTER WEST WARD You can vote for all four of our candidates for the City Council on the green ballot paper MARTYN PHILIPPA BELL BUDGE LES JULIA HIXSON WILSHIRE Martyn Bell (01903 530700 or [email protected]) is the Chairman of Chichester District Council, appointed in 2013. He has represented Chichester West as a City Councillor since 2007 and as a District Councillor since 2011. He will continue to support the activities of Residents’ Associations in West Ward and Community Safety initiatives such as the Parklands Neighbourhood Management Panel. He participated in the campaigns for a footbridge at the Fishbourne Road East railway crossing, protection of Henty Field from possible devel- opment and 20’s Plenty in residential areas. Philippa Budge (01243 780121 or [email protected]) moved to Chichester in 1976 when she worked as a teacher. Her children attended local schools while she joined local clubs including the Women’s Institute and the Horticultural Society. Her husband Peter has been a councillor for the last four years. She has observed his work in the community and, now fully retired , she also wants to put something back for the West Ward residents. Leslie Hixson (07923 948928 or [email protected]) ran a successful printing business where he trained apprentices and encouraged personal development. In retirement he supported various voluntary organisations, including The Children’s Society and local clubs mentoring children with low self-esteem or excluded. He sat on the Youth Justice Panel, worked with Home Start helping young families, and provided mentoring to patients with brain injuries. -

Parish: Chichester Ward: Chichester North CC/16/03119/ADV Proposal

Parish: Ward: Chichester Chichester North CC/16/03119/ADV Proposal 4 no. non-illuminated sponsorship signs and 4 no. non-illuminated plaques on planter. Site Priory Park, Priory Lane, Chichester, West Sussex Map Ref (E) 486295 (N) 105108 Applicant Chichester District Council RECOMMENDATION TO PERMIT Note: Do not scale from map. For information only. Reproduced NOT TO from the Ordnance Survey Mapping with the permission of the SCALE controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Crown Copyright. License No. 100018803 1.0 Reason for Committee Referral: Applicant is Chichester District Council 2.0 The Proposal 2.1 The proposal is to add a sponsorship sign to each of the 2 ‘welcome/entrance’ signs to the park; a sponsorship sign to each of the 2 ‘play area’ signs and 4 sponsorship signs to each side of the planter by the Guildhall within the Park. The measurements of the proposed signs are as follows: Sign 1 (x2) Total height of existing sign; 1920mm. Proposed sponsorship sign; 150mm (h) x 120mm (wide). Sign 2 (x2) Total height of existing sign; 1775mm Proposed sponsorship sign; 100mm (h) x 580mm (wide) Sign 3 (x4) Four sponsorship signs to be displayed centrally on four sides of an existing planter. They would measure 350mm (wide) x 200mm (high). The materials for the advertisements would include metal panels with vinyl. 3.0 The Site and Surroundings The application site is located within the heart of the city centre and comprises a historic public park within the Chichester conservation area. The park has many mature trees that are protected by preservation orders. -

Chichester District Council

Chichester District Council Planning Committee Wednesday 02 October 2019 Report of the Director Of Planning and Environment Services Schedule of Planning Appeals, Court and Policy Matters Between 16-Aug-2019 and 16- Sep-2019 This report updates Planning Committee members on current appeals and other matters. It would be of assistance if specific questions on individual cases could be directed to officers in advance of the meeting. Note for public viewing via Chichester District Council web siteTo read each file in detail, including the full appeal decision when it is issued, click on the reference number (NB certain enforcement cases are not open for public inspection, but you will be able to see the key papers via the automatic link to the Planning Inspectorate). * - Committee level decision. 1. NEW APPEALS (Lodged) Reference/Procedure Proposal 19/00350/LBC Hardings Farm Selsey Road Donnington Chichester West Donnington Parish Sussex PO20 7PU - Replacement of 8 no. windows to North, East and South Elevations (like for like). Case Officer: Maria Tomlinson Written Representation 18/00187/CONMHC Fisher Granary Fisher Lane South Mundham Chichester North Mundham Parish West Sussex PO20 1ND - Appeal against NM/29 Case Officer: Tara Lang Written Representation 18/00100/CONCOU Northshore Yacht Limited The Street Itchenor Chichester West Itchenor Parish West Sussex PO20 7AY - Appeal against WI/16 Case Officer: Steven Pattie Written Representation 19/00405/FUL Fisher Granary Fisher Lane South Mundham PO20 1ND - North Mundham Parish Use of land for the stationing of a caravan for use as a holiday let. Case Officer: Caitlin Boddy Written Representation 19/00046/CONCOU Kellys Farm Bell Lane Birdham Chichester West Sussex Birdham Parish PO20 7HY – Appeal against BI/46 Case Officer: Steven Pattie Written Representation 2. -

The West Sussex (Electoral Changes) Order 2016

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2016 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The West Sussex (Electoral Changes) Order 2016 Made - - - - Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2), (3), (4) and (5) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009(a) (“the Act”), the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated August 2016 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the county of West Sussex. The Commission has decided to give effect to those recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before each House of Parliament, a period of forty days has expired since the day on which it was laid and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act. Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the West Sussex (Electoral Changes) Order 2016. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after the day on which this Order is made. (3) Article 3 comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary, or relating, to the election of councillors, on the day after the day on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in England and Wales(c) in 2017. -

NOTICE of ELECTION CHICHESTER DISTRICT COUNCIL 2 MAY 2019 1 Elections Are to Be Held of Councillors for the Following Wards

NOTICE OF ELECTION CHICHESTER DISTRICT COUNCIL 2 MAY 2019 1 Elections are to be held of Councillors for the following Wards :- Ward Number of Councillors to be elected CHICHESTER CENTRAL 1 CHICHESTER EAST 2 CHICHESTER NORTH 2 CHICHESTER SOUTH 2 CHICHESTER WEST 2 EASEBOURNE (Parishes of Easebourne, Heyshott and Lodsworth) 1 FERNHURST (Parishes of Fernhurst, Lurgashall, Linch, Linchmere and Milland) 2 FITTLEWORTH (Parishes of Barlavington, Bignor, Bury, Duncton, East Lavington, 1 Fittleworth, Graffham, Stopham and Sutton) GOODWOOD (Parishes of Boxgrove, Eartham, East Dean, Singleton, Upwaltham, West Dean 1 and Westhampnett) HARBOUR VILLAGES (Parishes of Appledram, Bosham, Chidham, Donnington and 3 Fishbourne) HARTING (Parishes of Elsted & Treyford, Harting, Nyewood, Rogate and Trotton) 1 LAVANT (Parishes of Funtington and Lavant) 1 LOXWOOD (Parishes of Ebernoe, Kirdford, Loxwood, Northchapel, Plaistow & Ifold and 2 Wisborough Green) MIDHURST (Parishes of Bepton, Cocking, Midhurst, Stedham with Iping (Iping Ward), 2 Stedham with Iping (Stedham Ward), West Lavington and Woolbedding with Redford) NORTH MUNDHAM AND TANGMERE (Parishes of Hunston, Tangmere, North Mundham and 2 Oving) PETWORTH (Parishes of Petworth and Tillington) 1 SELSEY SOUTH (Parish of Selsey South Ward) 2 SIDDLESHAM WITH SELSEY NORTH (Parishes of Siddlesham and Selsey North Ward) 2 SOUTHBOURNE (Parish of Southbourne) 2 THE WITTERINGS (Parishes of Birdham, Earnley, East Wittering, Itchenor and West 3 Wittering) WESTBOURNE (Parishes of Compton, Marden, Stoughton and Westbourne) 1 2. Nomination papers may be obtained from the Elections Office at East Pallant House, Chichester, and must be delivered there on any day after the date of this notice but not later than 4PM on Wednesday, 3 APRIL 2019. -

Chichester East Ward

NOTICE OF ELECTION Election of a District Councillor to fill a casual vacancy in the Chichester East Ward. Number of Councillors Ward to be elected Chichester East One 1. Forms of nomination for the Election may be obtained at East Pallant House, 1 East Pallant, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 1TY from the Returning Officer who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer, East Pallant House, 1 East Pallant, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 1TY on any day after the date of this notice but no later than 4pm on Thursday, 27 May 2021. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday, 24 June 2021 from 7.00am to 10.00pm. 4. Applications to register to vote must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by midnight on Tuesday 8 June 2021. Applications can be made online: https://www.gov.uk/register-to- vote. 5. Applications to vote by emergency proxy at this election must be on the grounds of physical incapacity or for work or because you have been told you need to self isolate. The physical incapacity must have occurred after 5pm on Wednesday 16 June 2021. To apply on the grounds of work/service, the person must have become aware that they cannot go to the polling station in person after 5pm on Wednesday 16 June 2021. 6. Applications to register to vote by post or proxy should be made to the Electoral Registration Officer at Chichester District Council, East Pallant House, 1 East Pallant, Chichester, West Sussex, -

Dutch Cottage, Itchenor, Chichester West Sussex

Itchenor, Chichester, West Sussex todansteehancock.com 01243 523723 Dutch Cottage, Itchenor, Chichester West Sussex Located just yards from the Itchenor Sailing Club, Dutch Cottage is ideal for sailing enthusiasts, offering a rare opportunity to acquire a detached home (2,074 sq ft), fully renovated to an exacting standard, with an emphasis on space and light sitting room | dining room | kitchen/breakfast room | study | family room | utility room | cloakroom | entrance hall 4 double bedrooms (1 en suite) | bathroom | garden | garden storage | off street parking Distances & Transport: Itchenor Sailing Club: 65 metres | West Wittering: 2 miles | Chichester: 6 miles Southampton Airport: 37 miles | Gatwick Airport: 53 miles | Central London: 74 miles Description: Situation: Occupying a stunning harbour village setting, Dutch This highly regarded and sought after harbour side village Cottage is ideally situated for ease of access to the water has a thriving sailing club and a multitude of moorings for and sailing club (approx. 65m distant). Recently renovated boats and yachts, subject to availability. The village has a throughout and extended this surprisingly spacious home beautiful church, village hall and, just around the corner, offers flexible living accommodation over two floors with the popular Ship Inn public house. Much of the surrounding an emphasis on space and light. A particular feature is countryside is designated an Area of Outstanding Natural the principal open-plan reception space to the rear with Beauty and the Chichester Harbour Conservancy ensures full width sliding doors to the garden, underfloor heating, that the character of the area is preserved. The Cathedral feature fireplace and kitchen with modern appliances and City of Chichester lies some 7½ miles to the north and plenty of storage. -

About West Sussex

Introduction About West Sussex Geography Environment 6 Geography of the county 29 Sustainability 30 Carbon emissions This edition of West Sussex Life Demographics 31 Renewable energy 9 Population 33 Energy consumption has four sections, three of which 10 Projected population 35 Fuel poverty are aligned with the three core 12 Population density 37 Waste disposal 13 Population change 39 Composition of waste priorities in the Future West 14 Country of birth, ethnicity 41 Mineral extraction Sussex Plan: and refugees 43 Natural environment 15 Religion and language 16 Marital status Health and wellbeing • Giving children the best 17 Internal migration 46 Physical activity 47 Obesity start in life Voting and elections 48 Drugs and alcohol • Championing the local 18 2015 General Election 50 Smoking 19 2016 EU Referendum 51 Sexual health economy 20 District councils 53 Statutory homelessness • Independent for longer in 21 West Sussex County 56 Rough sleepers Council 57 Mental health later life 59 Learning disabilities Transport 60 Personal wellbeing 23 Railways This first section contains 24 Road network and traffic Community safety information on a variety of flows 61 Recorded crime Sussex West About 25 Road casualties and bus 64 Restorative Justice subjects that are relevant to the transport 66 Domestic abuse county’s population as a whole. 26 National Transport Survey 69 Sexual offences 27 Highways enquiries 72 Hate incidents and crime 28 Cycle paths 74 Fire and rescue Section Contents [email protected] West Sussex County Council -

S106 Financial Covenant Details

S106 Appendix 4 - New agreements 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 Ward App No Address Signed Obligation Type Amount Flat Farm , Broad Road, Hambrook, Bosham 16/04148/FUL Chidham, PO18 8RF 31/08/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 1,991.00 Bosham 17/01783/FUL 32 Williams Road, Bosham, PO18 8JS 11/08/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 181.00 The Oaks , Main Road, Bosham, PO18 Bosham 17/01800/FUL 8PH 23/11/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 181.00 Jutland House , Kiln Drive, Hambrook, Bosham 17/02254/FUL PO18 8FJ 12/12/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 1,448.00 Building North Of 1 , Chidham Lane, Bosham 17/02650/FUL Chidham, PO18 8TL 07/12/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 181.00 79 Oving Road, Chichester, West Sussex, Chichester East 17/00763/FUL PO19 7EW 06/06/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 181.00 Land North Of 1 To 4, Riverside, Chichester East 17/02248/FUL Chichester, West Sussex 07/02/2018 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 724.00 Chichester Graylingwell Hospital , College Lane, North 14/01018/OUT Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 6PQ 21/03/2018 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 7,783.00 Chichester Graylingwell Hospital , College Lane, North 14/01018/OUT Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 6PQ 21/03/2018 Waste & Recycling 900.00 Chichester 18 Lavant Road, Chichester, West Sussex, North 16/03484/FUL PO19 5RG 26/07/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 362.00 Chichester 3 The Boardwalk, Northgate, Chichester, North 17/00974/FUL West Sussex 13/10/2017 Recreation Disturbance Chichester 905.00 Chichester Lever House , Lavant -

Parking Zone Allocations: Wards in District Or Borough

Hillside Buckingham Manor Peverel Cokeham Southlands St. Nicolas Mash Barn St. Mary's Southwick Green Eastbrook Marine Widewater Churchill Legend Zone 1 (1) Zone 2 (4) Zone 3 (2) Zone 4 (7) Zone 5 (0) Reproduced from or based upon 2019 Ordnance Survey mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO © Crown Copyright reserved. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to Regional Parking Zone Allocation: Adur District - Appendix C-1 prosecution or civil proceedings West Sussex County Council Licence No. 100023447 1:30,000 ± Arundel & Walberton Angmering & Findon Barnham Ferring Courtwick with Toddington Brookfield Yapton East Preston Felpham East River Beach Rustington West Bersted Rustington East Middleton-on-Sea Hotham Pevensey Orchard Felpham West Pagham Marine Aldwick East Aldwick West Legend Zone 1 (2) Zone 2 (13) Zone 3 (0) Zone 4 (8) Zone 5 (0) Reproduced from or based upon 2019 Ordnance Survey mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO © Crown Copyright reserved. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to Regional Parking Zone Allocation: Arun District - Appendix C-2 prosecution or civil proceedings West Sussex County Council Licence No. 100023447 1:80,000 ± Fernhurst Loxwood Petworth Easebourne Harting Midhurst Fittleworth Westbourne Goodwood Lavant Chichester North Chichester West Chichester East Chichester Central Chichester South Southbourne Harbour Villages North Mundham & Tangmere The Witterings Sidlesham with Selsey North Legend Selsey South Zone 1 (13) Zone 2 (3) Zone 3 (2) Zone 4 (0) Zone 5 (3) Reproduced from or based upon 2019 Ordnance Survey mapping with permission of the Controller of HMSO © Crown Copyright reserved. Regional Parking Zone Allocation Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings West Sussex County Council Licence No. -

Corporate Plan 2018-2021

Corporate Plan 2018-21 www.chichester.gov.uk/corporateplan Our Vision Our Objectives Chichester District: a place where businesses can flourish; where Improve the provision of and access to suitable housing communities are active and happy; where residents and visitors can find • Increase the supply of suitable housing in the right location. fulfilling cultural, leisure and sporting activities; and where a good quality • Ensure housing is used effectively and is fit for purpose. of life is open to all. • Provide support for those that need it. Our Priorities Support our communities • Improve the provision of and access to suitable housing. • Provide support to communities and individuals who are vulnerable. • Support our communities. • Work together to help people feel safe. • Manage our built and natural environments to promote and maintain • Help our communities to be healthy and active. a positive sense of place. • Improve and support the local economy to enable appropriate Manage our built and natural environments to promote local growth. and maintain a positive sense of place • Manage the Council’s finances prudently and effectively. • Promote quality development and recognise the importance of the natural environment. • Encourage sustainable living. • Maintain clean, pleasant and safe public places. • Support the provision of essential infrastructure. • Help improve our City, Towns and Local Centres’ accessibility and attractiveness. Improve and support the local economy to enable appropriate local growth • Promote commercial activity and economic growth. • Promote Chichester District as a leading visitor and cultural destination. • Promote the City, Towns and Local Centres as vibrant places to do business. Manage the Council’s finances prudently and effectively Corporate Plan 2018-21 • Ensure the prudent use of the Council’s resources.