CS 61C: Great Ideas in Computer Architecture Dependability: Parity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIC Serial Communication Modules

PIC Serial Communication Modules Synchronous Serial Port (SSP Module) {clock signal is required} - Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) - Inter Integrated Circuit (IIC -> I2C) Serial Interface Asynchronous Communication Modules (clock signal is not required) - Universal Asynchronous Receiver Transmitter (UART) UART • A Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter (UART) is used for serial communications – usually via a cable. • The UART generates signals with the same timing as the RS-232 standard used by the Personal Computer’s COM ports. • The UART input/output uses 0V for logic 0 and 5V for logic 1. • The RS-232 standard (and the COM port) use +12V for logic 0 and –12V for logic 1. • To convert between these voltages levels we need an additional integrated circuit (such as Maxim’s MAX232). Parts of an RS-232 Frame • A frame transmits a single character and is in general composed of: 1) A start bit (always logic 0) 2) Data bits (5, 6, 7, or 8 of them) 3) A parity bit (optional, even or odd parity) 4) A stop bit (always logic 1) RS232 Level Converter PIC & MAX232 Connection UART Timing Accuracy • Since the transmitter and receiver keep track of time independently between clock recovery synchronization points, the combined inaccuracy of the transmitter and receiver’s clocks can not be too large. • For RS-232 communication, this combined inaccuracy is about 5%. • Usually, an RC oscillator is too inaccurate and a crystal is required. UART Bit Time and Baud Rate • The bit time (units of time) is the time from the start of one serial data bit value to the start of another. -

What the Heck Is RS-232 Anyway…

Tech Note What the heck is RS-232 anyway… It just occurred to me that there is an entire generation of technicians in the work force that did not grow up in the days of the TRS-80 and Commodore 64 PC. Rather, they were brought up on broadband and Wi-Fi. To them that funny looking 9-Pin connector that we old folks cut our teeth on is a mystery full of uncertainty and doubt – with a little bit of fear mixed in for good measure. In this paper, I hope to dispel some of the mystery and give you the essentials of RS-232. What is it? At one time, RS-232 / EIA-232 was the most widely used communication standard on the planet. It was defined and redefined many times. The “EIA” stands for “Electronic Industries Association” and the “RS” stands for “Recommended Standard.” That being the case, it was always rather loose. The physical characteristics of the hardware include both a 25 pin and 9 pin D sub connector. RS- 232 is capable of operating at data rates up to 20 Kbps and can push data about 50 ft. The absolute maximum data rate is difficult to nail down due the differences in the transmission line and cable length. It is possible to operate at some pretty high data rates if the distance is short. The voltage levels are defined as a range from -12 to +12 volts. RS-232 is also single ended. This means that a single electrical signal is compared to a common signal (ground) to determine binary logic states. -

Design and Its Application of Microprocessor

Design and Its application of Microprocessor The 8088 And 8086 Microprocessors: Programming, Interfacing, Software, Hardware And Applications Suk-Ju Kang Dong-A University [email protected] 1 Chapter 9. Memory Devices, Circuits, and Subsystem Design 2 In This Chapter, … 9.1 Program and Data Storage 9.2 Read-Only Memory 9.3 Random Access Read/Write Memories 9.4 Parity, the Parity Bit, and Parity- Checker/Generator Circuit 9.5 FLASH Memory 9.6 Wait-State Circuitry 9.7 8088/8086 Microcomputer System Memory Circuitry 3 Program and Data Storage The memory unit of a microcomputer is partitioned into a primary storage section and secondary storage section 4 Program and Data Storage The basic input/output system (BIOS) are programs held in ROM. ◦ They are called firmware because of their permanent nature ◦ The typical size of a BIOS ROM used in a PC today is 256 Kbytes Programs are normally read in from the secondary memory storage device, stored in the program storage part of memory, and then run 5 Read-Only Memory ROM, PROM, and EPROM ◦ Mask-programmable read-only memory (ROM) ◦ One-time-programmable read-only memory (PROM) ◦ Erasable read-only memory (EPROM) 6 Read-Only Memory Block diagram of a read-only memory Address bus ◦ Data bus ◦ Control bus Chip enable (CE) Output enable (OE) 7 Read-Only Memory Read operation 8 Random Access Read/Write Memories The memory section of a microcomputer system is normally formed from both read-only memories and random access read/write memories (RAM) RAM is different from ROM in two ways: ◦ Data stored in RAM is not permanent in nature RAM is normally used to store temporary data and application programs for execution ◦ RAM is volatile If power is removed from RAM, the stored data are lost 9 Random Access Read/Write Memories Static and dynamic RAMs ◦ For a static RAM (SRAM), data remain valid as long as the power supply is not turned off. -

Mass-Storage

Mass-Storage ICS332 - Fall 2017 Operating Systems Henri Casanova ([email protected]) Magnetic Disks ! Magnetic disks (a.k.a. “hard drives”) are (still) the most common secondary storage devices today ! They are “messy” " Errors, bad blocks, missed seeks, moving parts ! And yet, the data they hold is critical ! The OS used to hide all the “messiness” from higher-level software " Programs shouldn’t have to know anything about the way the disk is built ! This has been done increasingly with help from the hardware " i.e., the disk controller ! What do hard drives look like? Hard Drive Structure Hard Drive access Access ! A hard drive requires a lot of information for an access " Platter #, sector #, track #, etc. ! Hard drives today are more complicated than the simple picture " e.g., sectors of different sizes to deal with varying densities and radial speeds with respect to the distance to the spindle ! Nowadays, hard drives comply with standard interfaces " EIDE, ATA, SATA, USB, Fiber Channel, SCSI ! The hard drives, in these interfaces, is seen as an array of logical blocks (512 bytes) ! The device, in hardware, does the translation between the block # and the platter #, sector #, track #, etc. ! This is good: " The kernel code to access the disk is straightforward " The controller can do a lot of work, e.g., transparently hiding bad blocks ! The cost is that some cool optimizations that the kernel could perhaps do are not possible, since all its hidden from it Hard Drive Performance ! We’ve said many times that hard drives are slow ! -

Transmission Media

Part 2 – Data Communication Reliability and Channel Coding Gail Hopkins Part 2 – Data Communication Introduction Types of error that can occur during transmission Techniques used to control errors 1 Part 2 – Data Communication Transmission Errors Much of the complexity of networks arises from susceptibility to interference that can cause: transmitted data to be lost or changed random data to appear Single-bit errors versus burst errors Errors also caused by equipment failures or equipment operating below standard Small errors in transmission are harder to detect than complete failures! Part 2 – Data Communication Categories of Error Interference E.g. EM radiation from other devices Distortion Physical systems distort signals Wires have capacitance and inductance – blocks signals at some frequencies Attenuation Weakening of signal with distance 2 Part 2 – Data Communication Tradeoffs with Error Detection/Correction Error detection adds overhead Designers need to decide whether to use error detection or not Consider a single bit error Not important for image transmission Could be hugely important for a bank transfer! Part 2 – Data Communication Errors and their Causes Type of Error Description Single Bit Error Single bit in a block of bits is changed. All other bits in the block are unchanged. Often due to very short- duration interference. Burst Error Multiple bits in a block of bits are changed. Often due to longer-duration interference. Erasure (Ambiguity) The signal that arrives at a receiver is ambiguous – i.e. doesn’t clearly correspond to either a logical 1 or logical 0. Can result from distortion or interference. From Comer, 2009 3 Part 2 – Data Communication Handling Channel Errors Channel coding – two schemes: Forward Error Correction (FEC) mechanisms Add additional information to the data to allow the receiver to check if it is correct Allow receiver to detect when an error has occurred, which bits have changed and compute correct values (some techniques). -

Technical Guide Blackpearl

eqw Spectra Logic’s BlackPearl® NAS Technical Guide Simple, Affordable, Flexible Data Storage Abstract The extended lifespan of data has led to previously unimagined complexities, regulation, use cases, and migration planning scenarios. To address the difficulties stemming from data growth, including minimizing errors that can be introduced as data migrates over the network and across storage technologies, a new kind of mid-tier, secondary storage is required that focuses not only on the cost required to store massive data, but also on protecting that data. September 2019 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 BlackPearl NAS – Solution Snapshot ............................................................................................................. 5 Data Growth Rates ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Flexible NAS Storage to Meet Data’s Mid-Life Demands ............................................................................ 11 Purpose-Built Storage for Mid-Tier Data .................................................................................................... 11 Disk Technologies ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Drive Types ................................................................................................................................................. -

Data-Integrity

Fundamentals of Data Representation: Error checking and correction When you send data across the internet or even from your USB to a computer you are sending millions upon millions of ones and zeros. What would happen if one of them got corrupted? Think of this situation: You are buying a new game from an online retailer and put £40 into the payment box. You click on send and the number 40 is sent to your bank stored in a byte: 00101000. Now imagine if the second most significant bit got corrupted on its way to the bank, and the bank received the following: 01101000. You'd be paying £104 for that game! Error Checking and Correction stops things like this happening. There are many ways to detect and correct corrupted data, we are going to learn two. Parity bits Sometime when you see ASCII code it only appears to have 7 bits. Surely they should be using a byte to represent a character, after all that would mean they could represent more characters than the measily 128 they can currently store (Note there is extended ASCII that uses the 8th bit as well but we don't need to cover that here). The eigth bit is used as a parity bit to detect that the data you have been sent is correct. It will not be able to tell you which digit is wrong, so it isn't corrective. There are two types of parity odd and even. If you think back to primary school you would have learnt about odd and even numbers, hold that thought, we are going to need it. -

Application Notes

Application Note - Magnetic Stripe Reader prefers the parity to be checked by the MPU and not the Interfacing the Card Reader to a USART then parity must be set to Disabled and word Microprocessor size must be set to 7 bits. When reading Track 2 or Track 3, parity must be set to OFF. This is because data The Mag-Tek Card Reader may be interfaced to a characters encoded on these two tracks are in 5 bit microprocessor unit (MPU) in a number of ways. words, including parity. The USART is limited to a Selection of the most suitable method will depend on the minimum word size of 5 bits only when parity is OFF. In system requirements and the MPU capabilities. The two this case, the USART treats the parity bit just like any most common methods are: other data bit, and the MPU should check for correct 1. Single-bit input programming. parity on each character. 2. USART (Universal Synchronous/Asynchronous Receiver - Transmitter such as NEC 82C51). In operation, the USART remains inactive until it recognizes the Start Sentinel character. Then it Single - Bit Input Programming becomes active and collects the data characters, frames This method of interface does not require any external the data, and presents it to the MPU. (In some chip to implement serial data communication between applications, this may not be suitable for reliable Start the Card Reader and an MPU. This function is done Sentinel detection; see the Detecting Start Sentinel through a software program that allows the MPU to discussion below.) transmit and receive data. -

Detecting and Correcting Bit Errors

Detecting and Correcting Bit Errors COS 463: Wireless Networks Lecture 8 Kyle Jamieson Bit errors on links • Links in a network go through hostile environments – Both wired, and wireless: Scattering Diffraction Reflection – Consequently, errors will occur on links – Today: How can we detect and correct these errors? • There is limited capacity available on any link – Tradeoff between link utilization & amount of error control 2 Today 1. Error control codes – Encoding and decoding fundamentals – Measuring a code’s error correcting power – Measuring a code’s overhead – Practical error control codes • Parity check, Hamming block code 2. Error detection codes – Cyclic redundancy check (CRC) 3 Where is error control coding used? • The techniques we’ll discuss today are pervasive throughout the internetworking stack Application • Based on theory, but broadly applicable in practice, in other areas: Transport – Hard disk drives Network – Optical media (CD, DVD, & c.) Link – Satellite, mobile communications Physical • In 463, we cover the “tip of the iceberg” in the Internetworking stack 4 Error control in the Internet stack • Transport layer – Internet Checksum (IC) over TCP/UDP header, data IC TCP payload TCP header 5 Error control in the Internet stack • Transport layer – Internet Checksum (IC) over TCP/UDP header, data IC TCP payload TCP header • Network layer (L3) – IC over IP header only IC IP payload IP header 6 Error control in the Internet stack • Transport layer – Internet Checksum (IC) over TCP/UDP header, data IC TCP payload TCP header -

Error Detection

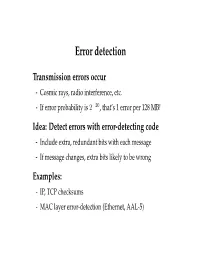

Error detection ² Transmission errors occur - Cosmic rays, radio interference, etc. - If error probability is 2¡20, that's 1 error per 128 MB! ² Idea: Detect errors with error-detecting code - Include extra, redundant bits with each message - If message changes, extra bits likely to be wrong ² Examples: - IP, TCP checksums - MAC layer error-detection (Ethernet, AAL-5) Parity ² Simplest scheme: Parity - For each 7-bits transmitted, transmit an 8th parity bit - Even parity means total number of 1 bits even - Odd parity means total number of 1 bits odd ² Detects any single-bit error (good) ² Only detects odd # of bit errors (not so good) ² Common errors not caught - E.g., error induces bunch of zeros, valid even parity ² Can we somehow have multiple parity bits? Background: Finite field notation ² Let Z2 designate field of integers modulo 2 - Two elements are 0 and 1, so an element is a bit - Can perform addition and multiplication, just reduce mod 2 - Example: 1 ¢ 1 = 1, 1 + 1 = 2 mod 2 = 0 ² Let Z2[x] be polynomials w. coefficients in Z2 n n¡1 - I.e., a0x + a1x + ¢ ¢ ¢ + an¡1x + an for ai 2 Z2 = f0; 1g - Each ai is a bit, so can represent polynomial compactly ² We can multiply, add, subtract polynomials - Example 1: (x + 1)(x + 1) = x2 + x + x + 1 = x2 + 1 (recall 1 + 1 ´ 0 (mod 2), so (1 + 1)x = 0) - Example 2: (x3 + x2 + 1) + (x2 + x) = x3 + x + 1 - Note addition & subtraction are both just XOR Hamming codes ² Idea: Use multiple parity bits over subsets of input - Will allow you to detect multiple errors - Technique is used by ECC memory -

Error Detection an Error Occurs When a Bit Is Altered Between

Error Detection ¾ An error occurs when a bit is altered between transmission and reception ¾ Single bit errors z only one bit altered z caused by white noise ¾ Burst errors z contiguous sequence of B bits in which first last and any number of intermediate bits in error z caused by impulse noise or by fading in wireless z effect greater at higher data rates Sources of Noise and Prevention Error Detection ¾ will have errors ¾ detect using error-detecting code (principle of redundancy) ¾ added by transmitter and recalculated and checked by receiver ¾ still chance of undetected error Error Detection Techniques • Parity checks • Longitudinal Redundancy Checking (LRC) • Polynomial checking – Checksum – Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) Parity Check • Oldest and simplest • Doesn’t catch all errors – If two (or an even number of) bits have been transmitted in error at the same time, the parity check appears to be correct – Detects about 50% of errors To be sent: Letter V in 7-bit ASCII: 0110101 Longitudinal Redundancy Checking (LRC) • Adds an additional character (instead of a bit) – Block Check Character (BCC) to each block of data – Determined like parity but, but counting longitudinally through the message (as well as vertically) • Major improvement over parity checking – 98% error detection rate for burst errors ( > 10 bits) – Less capable of detecting single bit errors Example: Determine the VRC and LRC for the following encoded message: THE_CAT. Use odd parity for the VRC and even parity for the LRC. Character T H E sp C A T LRC Hex 54 48 45 20 43 41 54 2F b0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 b1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 b2 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 b3 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 b4 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 b5 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 b6 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 Parity bit b7 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 (VRC) The LRC is 00101111 in binary (2F) which is the character (/). -

Modern RAID Technology

Modern RAID Technology RAID Primer A Configuration Guide Excellence in Controllers Modern RAID Technology RAID Primer A Configuration Guide 6th Edition © Copyright 1997-2003 ICP vortex Computersysteme GmbH Konrad-Zuse-Str. 9 D-74172 Neckarsulm - Germany About this RAID Primer This RAID Primer is intended as a guide to help the reader determine which PCISCSI disk array controller and which RAID level are appropriate for a given system configuration. Various configurations are presented, which will give the reader a wide variety of options. By increasing the reader’s understanding of RAID configurations, and the many enhancements to system efficiency that RAID provides, we are removing the mystery that surrounds RAID. If there are questions or further information is needed, please contact: ICP vortex Computersysteme GmbH, Phone: +4971329620800 or 900, Fax: +4971329620200 5 6 Introduction What is RAID? 8 Part I RAID Levels How are the Drives Organized? 9 RAID 0 or Data Striping 9 RAID 1 or Drive Mirroring / Drive Duplexing 9 RAID 2 or Hamming System 10 RAID 3 or Byte Striping with Parity Drive 10 RAID 4 or Block Striping with Parity Drive 11 RAID 5 or Block Striping with Striped Parity 12 RAID 10 or Mirrored Striping Array 12 Part II Typical Configuration Examples 13 1. NT or Unix* Workstation 13 2. Fast Workstation Working with Large Files 14 3. Small NetWare* Server (36 GB) 14 4. Small Windows* NT or Unix* Server (36 GB) 16 Add more Capacity 17 5. Mid size NetWare* File Server (72 GB) 18 Add Capacity to the Mid size NetWare* File Server 19 Adding Speed and Redundancy to the Server 20 6.