Is There Really an Aspectual Se in Spanish?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Verbs in Relation to Verb Complementation 11-69

1168 Complementation of verbs and adjectives Verbs in relation to verb complementation 11-69 They may be either copular (clause pattern SVC), or complex transitive verbs, or monotransitive verbs with a noun phrase object), we can give only (clause pattern SVOC): a sample of common verbs. In any case, it should be borne in mind that the list of verbs conforming to a given pattern is difficult to specífy exactly: there SVC: break even, plead guilty, Iie 101V are many differences between one variety of English and another in respect SVOC: cut N short, work N loose, rub N dry of individual verbs, and many cases of marginal acceptability. Sometimes the idiom contains additional elements, such as an infinitive (play hard to gel) or a preposition (ride roughshod over ...). Note The term 'valency' (or 'valencc') is sometimes used, instead of complementation, ror the way in (The 'N' aboye indicates a direct object in the case oftransitive examples.) which a verb determines the kinds and number of elements that can accompany it in the clause. Valency, however, incIudes the subject 01' the clause, which is excluded (unless extraposed) from (b) VERB-VERB COMBINATIONS complementation. In these idiomatic constructions (ef 3.49-51, 16.52), the second verb is nonfinite, and may be either an infinitive: Verbs in intransitive function 16.19 Where no eomplementation oecurs, the verb is said to have an INTRANSITIVE make do with, make (N) do, let (N) go, let (N) be use. Three types of verb may be mentioned in this category: or a participle, with or without a following preposition: (l) 'PURE' INTRANSITIVE VERas, which do not take an object at aH (or at put paid to, get rid oJ, have done with least do so only very rarely): leave N standing, send N paeking, knock N fiying, get going John has arrived. -

Ditransitive Constructions Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig (Germany) 23-25 November 2007

Conference on Ditransitive Constructions Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig (Germany) 23-25 November 2007 Abstracts On “Dimonotransitive” Structures in English Carmen Aguilera Carnerero University of Granada Ditransitive structures have been prototypically defined as those combinations of a ditransitive verb with an indirect object and a direct object. However, although in the prototypical ditransitive construction in English, both objects are present, there is often omission of one of the constituentes, usually the indirect object. The absence of the indirect object has been justified on the basis of the irrelevance of its specification or the possibility of recovering it from the context. The absence of the direct object, on the other hand, is not so common and only occur with a restricted number of verbs (e.g. pay, show or tell).This type of sentences have been called “dimonotransitives” by Nelson, Wallis and Aarts (2002) and the sole presence in the syntactic structure arises some interesting questions we want to clarify in this article, such as: (a) the degree of syntactic and semantic obligatoriness of indirect objects and certain ditransitive verbs (b) the syntactic behaviour of indirect objects in absence of the direct object, in other words, does the Oi take over some of the properties of typical direct objects as Huddleston and Pullum suggest? (c) The semantic and pragmatic interpretations of the missing element. To carry out our analysis, we will adopt a corpus –based approach and especifically we will use the International Corpus of English (ICE) for the most frequent ditransitive verbs (Mukherjee 2005) and the British National Corpus (BNC) for the not so frequent verbs. -

Transitive Verb

Transitive verb This article needs additional citations for verification. Learn more A transitive verb is a verb that accepts one or more objects. This contrasts with intransitive verbs, which do not have objects. Transitivity is traditionally thought a global property of a clause, by which activity is transferred from an agent to a patient.[1] Transitive verbs can be classified by the number of objects they require. Verbs that accept only two arguments, a subject and a single direct object, are monotransitive. Verbs that accept two objects, a direct object and an indirect object, are ditransitive,[2] or less commonly bitransitive.[3] An example of a ditransitive verb in English is the verb to give, which may feature a subject, an indirect object, and a direct object: John gave Mary the book. Verbs that take three objects are tritransitive.[4] In English a tritransitive verb features an indirect object, a direct object, and a prepositional phrase – as in I'll trade you this bicycle for your binoculars – or else a clause that behaves like an argument – as in I bet you a pound that he has forgotten.[5] Not all descriptive grammars recognize tritransitive verbs.[6] A clause with a prepositional phrase that expresses a meaning similar to that usually expressed by an object may be called pseudo-transitive. For example, the Indonesian sentences Dia masuk sekolah ("He attended school") and Dia masuk ke sekolah ("He went into the school") have the same verb (masuk "enter"), but the first sentence has a direct object while the second has a prepositional phrase in its place.[7] A clause with a direct object plus a prepositional phrase may be called pseudo-ditransitive, as in the Lakhota sentence Haŋpíkčeka kiŋ lená wé-čage ("I made those moccasins for him").[8] Such constructions are sometimes called complex transitive. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

The Relationship Between Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in English Language

NOTION NOTION Volume 01, Number 02, November 2019 p. 62-67 The Relationship between Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in English Language Teddy Fiktorius SMA Bina Mulia Pontianak, Kalimantan Barat, Indonesia [email protected] Article Info ABSTRACT Article History In the current research, the researcher employs descriptive method (library Article Received research) to elaborate on the relationship and differentiation between the 17th August 2019 English language transitive and intransitive verbs. The first parts explore the Article Reviewed theoretical framework of the relationship and differentiation equipped with 9th September 2019 various sentences samples. The next part discusses the implications for English Article Accepted language teachers in coping with some grammatical confusion. Finally, some 11 October 2019 solutions as well as recommendations are proposed. Keywords transitive verbs intransitive verbs grammatical confusion I. INTRODUCTION misleading sentences that lose its exact meaning. Verbs can be so tricky that even the best grammar Students, particularly the speakers of other languages, students might be often confounded by the difference often have difficulty determining which verbs require between transitive and intransitive verbs. The an object, and which do not. When students confuse confusion with the use of the transitive and transitive and intransitive verbs, the sentences they intransitive verbs can be resolved as a grammar point construct both orally and in written may be becomes clear with an understanding of objects. incomplete. When using a dictionary to look up verbs, we may This current paper is written to provide us with have been puzzled by the abbreviations vi (intransitive better insights into the difference of transitive and verb) and vt (transitive verb). -

A Verb Expresses Action Or a State of Being. Verbs Are Classified in 3 Ways

Verbs A verb expresses action or a state of being. Verbs are classified in 3 ways: As helping or main verbs As action or linking verbs As transitive or intransitive verbs 1. Main Verbs and Helping Verbs A helping verb may be separated from the main verb. A verb phrase consists of one main verb and one or more helping verbs. Examples I am reading Gulliver’s Travels. We should have been listening instead of talking. Did she paint the house? Commonly Used Helping Verbs Forms of BE A modal is an auxiliary am, is, are, was, were, verb that is used to be, being, been express an attitude toward the action or state of being of the Forms of HAVE main verb. have, having, has, had MODALS can, could, may, might, Forms of DO must, ought, shall, do, does, did should, will, would Not and the contraction of n’t are never part of a verb phrase Instead, they are adverbs telling to what extent. We did not hear you. We didn’t hear you. 2. Action Verbs and Linking Verbs An action verb expresses either physical or mental activity. A linking verb connects the subject to a word or word group that identifies or describes the subject. Such a word group is called a subject complement. Commonly Used Linking Verbs Forms of Be be were shall have been should be being shall be will have been would be am will be can be could be is has been may be should have been are have been might be would have been was had been must be could have been Other Linking Verbs appear feel look seem sound taste become grow remain smell stay turn Depending on how these words are used in a sentence, they can be classified as linking or action verbs. -

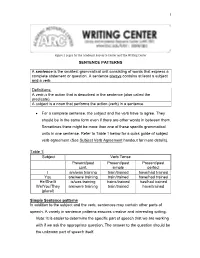

1 SENTENCE PATTERNS a Sentence Is the Smallest Grammatical Unit

1 Figure 1 Logos for the Academic Resource Center and The Writing Center SENTENCE PATTERNS A sentence is the smallest grammatical unit consisting of words that express a complete statement or question. A sentence always contains at least a subject and a verb. Definitions: A verb is the action that is described in the sentence (also called the predicate). A subject is a noun that performs the action (verb) in a sentence. • For a complete sentence, the subject and the verb have to agree. They should be in the same form even if there are other words in between them. Sometimes there might be more than one of these specific grammatical units in one sentence. Refer to Table 1 below for a quick guide of subject verb agreement (See Subject Verb Agreement handout for more details). Table 1 Subject Verb Tense Present/past Present/past Present/past cont. simple perfect I am/was training train/trained have/had trained You are/were training train/trained have/had trained He/She/It is/was training trains/trained has/had trained We/You/They are/were training train/trained have/trained (plural) Simple Sentence patterns In addition to the subject and the verb, sentences may contain other parts of speech. A variety in sentence patterns ensures creative and interesting writing. Note: It is easier to determine the specific part of speech that we are working with if we ask the appropriate question. The answer to the question should be the unknown part of speech itself. 2 The six major simple sentence patterns are as follows. -

Transitive & Intransitive Verbs

Transitive & Intransitive verbs Name__________________________________________________________________ Period________ There are two kinds of action verbs: transitive and intransitive. A transitive verb has a direct object. EXAMPLE: Columbus discovered America. An intransitive verb does not need an object to complete its meaning. EXAMPLES: The wind howled. He is afraid. Underline the predicate twice, and classify it as transitive or intransitive in the blank space. Find the direct object(s) in each transitive sentence and circle it. 1. Leroy paid the extremely high cellular phone bill as my birthday present. TRANSITIVE_____ 2. Ornithology is the study of various types of birds. ___________________________ 3. Move those big purple blocks that are in my way, now! ___________________________ 4. Everyone listened carefully to the talkative teacher. ___________________________ 5. The tired workers wore special uniforms to work at the concert. ___________________________ 6. We built a barbecue pit in our backyard to celebrate my birthday. ___________________________ 7. What is the name of this hanging picture? ___________________________ 8. He lives in Germany by a beautiful sparkling lake. ___________________________ 9. Who elected the principal of Campbell High School? ___________________________ 10. We walked into the brand new school for the first time. ___________________________ 11. We send many good customers to them to buy weave. ___________________________ 12. London is the foggy capital city of Great Britain. ___________________________ 13. Frank drew many excellent cartoons to make fun of his math teacher. ___________________________ 14. We study hard for the Spanish tests in Mrs. Torres’s class. ___________________________ 15. The frightened children cried loudly when they saw the monster in the closet. ___________________________ 16. Lora made this awesome poster for her project in Mr. -

Parts of Speech Overview Verb, Adverb, Preposition, Conjunction, Interjection

NL_EOL_SE08_P1_C03_096-123.qxd 8/7/07 9:10 AM Page 96 CHAPTER Parts of Speech Overview Verb, Adverb, Preposition, Conjunction, Interjection Diagnostic Preview A. Identifying Different Parts of Speech Identify each italicized word or word group in the following HELP sentences as a verb, an adverb, a preposition, or a conjunction. For Keep in mind each verb, indicate whether it is an action verb or a linking verb. that correlative EXAMPLE 1. You probably know that Christopher Columbus was a conjunctions can be made famous explorer, but do you know anything of his up of more than one word. personal life? 1. but—conjunction; of—preposition 1. I have discovered some interesting facts about Christopher Columbus. 2. He was born into a hard-working Italian family and learned how to sail as a boy. 3. He became, in fact, not only a master sailor but also a map maker. 4. Although he had barely any formal education, he studied both Portuguese and Spanish. 5. The writings of ancient scholars about astronomy and geog- raphy especially interested him. 96 Chapter 3 Parts of Speech Overview NL_EOL_SE08_P1_C03_096-123.qxd 8/7/07 9:10 AM Page 97 3 6. Columbus apparently also had keen powers of observation. a 7. These served him well on his expeditions. 8. On his voyages to find a sea route to the East Indies, Columbus was a determined, optimistic leader. 9. He let neither doubters nor hardships interfere with his plans. 10. Many people mistakenly think that Columbus was poor when he died in 1506, but he was actually quite wealthy. -

Associated Motion with Deictic Directionals: a Comparative Overview Aicha Belkadi [email protected]

SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics Vol. 17 (2015): 49-76 Associated motion with deictic directionals: A comparative overview Aicha Belkadi [email protected] 1. Introduction This paper focusses on deictic directionals and their rarely discussed function as markers of Associated Motion (henceforth AM). AM is a term generally used to refer to a category of verbal affixes exhibited by a number of indigenous Australian, North American and South American languages, whose function is to indicate that the event encoded by a verb is framed with respect to a motion co-event (Koch, 1984; Wilkins, 2005; Guillaume, 2009 amongst others). The most characteristic systems of AM involve complex paradigms, where affixes are each paired with specific and quite sophisticated types of motion. Specifications may encode information about the direction and orientation of the motion event, a defined temporal relation with the verb’s event, and particular aspectual notions. The examples below from the Australian languages Mparntwe Arrernte and Adnyamathanha illustrate some of the possibilities. (1) Mparntwe Arrernte (Australia: Wilkins, 2006) angk-artn.alpe-ke speak-QUICK:DO&GO.BACK-pc ‘Quickly spoke and then went back.’ (2) Adnyamathanha (Australia, Tunbridge, 1988) yarta veni witi-nali-angg-alu ground very pierce-CONT.COMING(sic)-PERF-3SG.ERG ‘It (a piece of iron hanging down from a truck) poked into the ground all the way (to here).’ The affix -artn- in (1) marks that the event of speaking, lexicalised by the verb, is followed by a motion of the subject directed away from the deictic anchor. In addition, it also provides some information about the speed in which this event enfolds. -

The Most Typical Ditransitive Verb? a Counterexample from Ainu (Oral Or Poster)

Is ‘GIVE’ the most typical ditransitive verb? A counterexample from Ainu (oral or poster) A ditransitive construction is defined as one consisting of an underived (ditransitive) verb, an agent argument (A), a recipient argument (R), and a theme argument (T); three-argument constructions containing participants with other semantic roles are not regarded as ditransitive (Mal’chukov et al, forthcoming). Much of the research on ditransitive constructions has been focused on the properties of the verb ‘give’ (e.g., Haspelmath 2005) which is often regarded as by far the most typical ditransitive verb because of its high formal and semantic transitivity (Kittilä 2006). I will discuss a case from the moribund Southern Hokkaido dialects of Ainu which might present a counterexample to Kittilä’s (2006: 604) Universal 1: “If a language has only one ditransitive trivalent verb (on the basis of any feature of formal transitivity), then that verb is ‘give’”. Ainu, a genetic isolate, is polysynthetic, agglutinating, predominantly head-marking with SV/AOV constituent order; morphological expression of arguments is tripartite. Arguments do not inflect for case: S, A and O are distinguished by their relative position in sentence structure and by obligatory verbal cross-referencing; obliques are marked by postpositions. The difference between intransitive and transitive verbs is clear-cut since they employ different verbal cross-referencing. Monotransitive and ditransitive verbs (the latter being conceived here as any three-argument verbs) are differentiated only by the number of unmarked objects. Ainu possesses a double-object construction as the only possible ditransitive type, since there is no morphosyntactic distinction between the two objects with respect to alignment properties (1b).1.