Baja California, Then and Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overall Finish Results 189 Entries Inaugural Lucenra SCORE Baja

Inaugural Lucenra SCORE Baja 400 Page 1 of 5 Ensenada Printed: 11/12/2019 8:53 pm * Penalty Applied September 21, 2019 Overall Finish Results 189 Entries Place Racer City, State Nbr Class Pos. Brand Laps Elapsed Group: A 1 Ryan Arciero Huntington Beach, CA 32 SCORE Trophy Truck 1 HEF 1 08:26:31.918 2 Andy Mc Millin San Diego, CA 31 SCORE Trophy Truck * 2 CHV 1 08:28:08.863 3 Tavo Vildosola Mexicali, BC 21 SCORE Trophy Truck * 3 CTM 1 08:28:55.694 4 Justin Lofton Brawley, CA 41 SCORE Trophy Truck 4 FOR 1 08:30:14.965 5 Alan Ampudia Ensenada, BC 10 SCORE Trophy Truck * 5 FOR 1 08:30:47.564 6 Cameron Steele San Clemente, CA 16 SCORE Trophy Truck 6 GEI 1 08:30:50.372 7 B. J. Baldwin Las Vegas, NV 97 SCORE Trophy Truck * 7 TOY 1 08:31:25.754 8 Justin Morgan El Cajon, CA 1X Pro Moto Unlimited 1 HON 1 08:32:29.892 9 Santiago Creel Mexico City, MX 66X Pro Moto Unlimited 2 KTM 1 08:32:36.032 10 Chris Miller Rancho Santa Fe, CA 40 SCORE Trophy Truck * 8 TOY 1 08:33:20.350 11 Ricky Jonson Lake Elsinore, CA 6 SCORE Trophy Truck 9 MAS 1 08:35:30.957 12 Bobby Pecoy Anaheim, CA 14 SCORE Trophy Truck 10 FOR 1 08:35:57.490 13 Bryce Menzies Las Vegas, NV 7 SCORE Trophy Truck 11 FOR 1 08:39:35.123 14 Luke Mc Millin El Cajon, CA 83 SCORE Trophy Truck 12 FOR 1 08:40:17.860 15 Mike Walser Comfort, TX 89 SCORE Trophy Truck 13 MAS 1 08:43:02.295 16 Robby Gordon Orange, CA 77 SCORE Trophy Truck * 14 CHV 1 08:44:07.231 17 Dave Taylor Page, AZ 26 SCORE Trophy Truck * 15 FOR 1 08:44:22.550 18 Troy Herbst Huntington Beach, CA 54 SCORE Trophy Truck 16 HEF 1 08:45:44.371 -

Comisi6n Estatal De Servicios P0blicos De Tijuana

COMISI6N ESTATAL DE SERVICIOS P0BLICOS DE TIJUANA Jullo2008 www.cuidoelagua.or 1- www.cespt.gob.mxg INDICE 1.- ANTECEDENTES CESPT (Cobertura de Agua y Eficiencia) 2.- EL AGUA COMO PROMOTOR DE DESARROLLO 3.- PROBLEMÁTICA BINACIONAL 4.- CERO DESCARGAS 5.- PROYECTO MORADO Y CERCA 6.- METAS CESPT 2013 1.-ANTECEDENTES CESPT I www.cespt.gob.mx ANTECEDENTES CESPT • Empresa descentralizada del Gobierno del estado encargada del servicio de agua potable y alcantarillado para las ciudades de Tijuana y Playas de Rosarito. • Más de 500,000 conexiones. • 1,764 empleados. • 7 Distritos de operación y mantenimiento. • 13 Centros de atención foráneos y 5 cajeros automáticos. • 3 Plantas potabilizadoras. • 13 plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales operadas por CESPT y una planta de tratamiento operada por los Estados unidos. • Arranque de una nueva planta de tratamiento de aguas residuales (Monte de los Olivos). • 90 % del suministro de agua proviene del Río Colorado (250 Kms de distancia y 1060 mts de altura) Cobertura de Agua y Eficiencia 50 46 43.9 41.9 42.2 42.2 40 41 40.1 38.9 38.2 CR EDIT 33.5 JA O P 31.5 PON LAN ES MAE 30 B STR ID 25 NA O, -BA 26.4 27.3 %-2 DB NO 2% ANK- 3 B 25.5 25.2 24.2 EPA 5%- RA 26.1 20% 25% S 24.8 23.5 20 21.7 21.5 19 . 2 19 18 . 8 18.5 10 0 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 CRECIMIENTO DE LA POBLACIÓN Eficiencia Física desde 1990 hasta 2009 1990 to 2009 58.1 % hasta 81.5 % 773,327 - 1,664,339 hab (115.3%) Promedio Anual 6.4 % COMUNICADO Fitch Rating• conflnna Ia callflc:aciOn de A+(mex) de Ia ComlsiOn Estatal de Servlclos P&lbllcos de Tijuana (CESPT) N.L. -

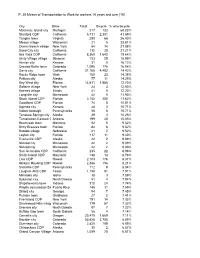

Copy of Censusdata

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

Arkansas V. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership Under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Frierson [email protected]

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 1997 | Issue 1 Article 16 Arkansas v. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Frierson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Recommended Citation Frierson, Katheryn Kim () "Arkansas v. Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership under the Clean Water Act," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1997: Iss. 1, Article 16. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1997/iss1/16 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arkansas v Oklahoma: Restoring the Notion of Partnership Under the Clean Water Act Katheryn Kim Friersont The long history of interstate water pollution disputes traces the steady rise of federal regulatory power in the area of environ- mental policy, culminating in the passage of the Clean Water Act Amendments of 1972.1 Arkansas v Oklahoma2 is the third and latest Supreme Court decision involving interstate water pol- lution since the passage of the 1972 amendments. By all ac- counts, Arkansas is wholly consistent with the Court's prior decisions. In Milwaukee v Illinois3 and InternationalPaper Co. v Ouellette,4 the Court held that the Clean Water Act ("CWA") preempted all traditional common law and state law remedies. Consequently, states lost much of their traditional authority to direct water pollution policies. Despite the claim that the CWA intended "a regulatory 'partnership' between the Federal Govern- ment and the source State", Milwaukee and InternationalPaper placed states in a subordinate position to the federal govern- t B.A. -

Transboundary Issues and Solutions in the San Diego/Tijuana Border

Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2 Why Do We Need to Re-think the Border Now? 6 3. Re-Defining the Border 7 4. Trans-Border Residents 9 5. Trans-National Residents 12 6. San Diego-Tijuana’s Comparative Advantages and Challenges 15 7. Identifying San Diego-Tijuana's Shared Regional Assets 18 8. Trans-Boundary Issues •Regional Planning 20 •Education 23 •Health 26 •Human Services 29 •Environment 32 •Arts & Culture 35 8. Building a Common Future: Promoting Binational Civic Participation & Building Social Capital in the San Diego-Tijuana Region 38 9. Taking the First Step: A Collective Binational Call for Civic Action 42 10. San Diego-Tijuana At a Glance 43 11. Definitions 44 12. San Diego-Tijuana Regional Map Inside Back Cover Copyright 2004, International Community Foundation, All rights reserved International Community Foundation 3 Executive Summary Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Over the years, the border has divided the people of San Diego Blurred Borders highlights the similarities, the inter-connections County and the municipality of Tijuana over a wide range of differ- and the challenges that San Diego and Tijuana share, addressing ences attributed to language, culture, national security, public the wide range of community based issues in what has become the safety and a host of other cross border issues ranging from human largest binational metropolitan area in North America. Of particu- migration to the environment. The ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality has lar interest is how the proximity of the border impacts the lives and become more pervasive following the tragedy of September 11, livelihoods of poor and under-served communities in both San 2001 with San Diegans focusing greater attention on terrorism and Diego County and the municipality of Tijuana as well as what can homeland security and the need to re-think immigration policy in be done to address their growing needs. -

John Lawrence of Saguache

COLORADO I : 'ACAS ~ A " '" ··:// ,,, : ' r •oun ~ r--R' -0 - 6'- A N-C -0 -_l___----, 0R A N 0 ) ••oc. ~~ GAR"<eo (S"M?-- The Town Boom in Las Animas and Baca Counties Morris F. Taylor was professor of history at Trinidad State Junior College until his death in 1979. Well known for his contribution to the historical scholarship of Colorado and New Mexico, he won two certificates of commendation for his writings from the American Asso ciation for State and Local History and the 1974 LeRoy R. Hafen Award for the best article in The Colorado Maga zine. His two major books are First Mail West: Stage Lines on the Santa Fe Trail (1971) and 0. P. McMains and the Maxwell Land Grant Conflict (1979). He held a mas ter's degree from Cornell University and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the Univer sity of Colorado in 1969. 112 THE COLORADO MAGAZINE 55/2 and 3 1978 Las Animas and Baca Counties 113 In the late 1880s southeastern Colorado experienced boom condi Town Company. Probably named for Two Buttes, a prominent land tions that were short-Jived. Several years of unusually good rainfall mark in that flat country, the place was abandoned the next year, most over much of the Great Plains had aroused unquestioning hopes and of the people moving to a new town, Minneapolis, which had a more speculative greeds, bringing on land rushes and urban developments attractive site not far away.5 In November of that year the incorpora that were the first steps toward the dust bowls of the twentieth century .1 tion papers of the Clyde Land and Town Company, signed by men Similar to the many land development schemes in the West today that from Kansas and Rhode Island and Las Animas County in Colorado, are unplanned, quick-profit enterprises, land rushes and town promo were filed with the Las Animas County clerk. -

Diagnóstico Socioambiental Para El Programa Del Manejo Integral Del Agua De La Cuenca Del Río Tijuana

Diagnóstico socioambiental para el Programa del Manejo Integral del Agua de la Cuenca del Río Tijuana Diagnóstico socioambiental para el Programa del Manejo Integral del Agua de la Cuenca del Río Tijuana Elaborado por: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte Coordinador Carlos A. de la Parra Rentería Colaboradores Mayra Patricia Melgar López Alfonso Camberos Urbina Tijuana, Baja California, 15 de marzo de 2017. i TABLA DE CONTENIDO PARTE I. MARCO DE REFERENCIA .......................................................... 1 UBICACIÓN, DELIMITACIÓN Y DESCRIPCIÓN GENERAL DE LA REGIÓN ................................................................. 1 La Cuenca del Río Tijuana .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Antecedentes Históricos .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Localización ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Descripción de los municipios y el condado que integran la CRT ..................................................................................... 5 Características físicas ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 POBLACIÓN EN LA CRT ...................................................................................................................................... -

AILA New Mexico/Oklahoma/Texas CHAPTER GRANT/FUNDING REQUEST CHECKLIST

AILA New Mexico/Oklahoma/Texas CHAPTER GRANT/FUNDING REQUEST CHECKLIST The AILA Texas/New Mexico/Oklahoma Chapter Grant/Funding Request Application process consists of the following components, which should be submitted in the order listed below. This checklist is provided to help ensure a complete proposal. It does not need to be submitted with the proposal. Section I: Cover Letter (one page) [Required] Include the purpose of the grant request and a brief description of how funds will be used by your organization. Section II: Grant/Funding Request Form [Required] Complete the 2-page template provided. Section III: Narrative [Optional] You may include a 2-page narrative regarding your organization, those being served & basis for funding request. To assist you in preparing your narrative, we are providing you with some topics to cover in your submission: Narrative Questions 1. Organization Background 2. Goals 3. Current Programs 4. Board/Governance: Number of Board Members 5. Staffing &Volunteers 6. Supervision & Planning Section IV: Attachments [Optional] In order to review your grant request, you may submit any or all of the following attachments: Financial Attachments 1. Organization budget 2. Year-end financial statements, audit and Sources of Income Table 3. Major contributors 4. In-kind contributions Other Attachments 1. Proof of IRS federal tax-exempt status, dated within the last five years 2. Annual Report or Independent Audit, if available; evaluation results (optional); the organization’s most recent evaluation results, relevant to this request. Timeline/Deadlines: A completed application must be received by the AILA Texas/New Mexico/Oklahoma Chapter Donations Committee Chair Jodi Goodwin at the address listed below by no later than February 1 for the year funding is requested. -

SAN Francisco and the 1911 BAJA CALIFORNIA REBELLION

THE DIVIDED CALIFORNIAS: SAN FRANcIsco AND THE 1911 BAJA CALIFORNIA REBELLION Jeffrey David Mitchell HE study of the 1911 Rebellion in Baja California del Norte, a Mexican Tpeninsula on the Pacific Coast best known to Americans for the region’s enclave ofexpatriates, locates an event from the early twentieth century that provides a glimpse into how a nation’s social, political, and economic patterns affect another nation. In this case, the rebellion reflects the dynamics of interdependence between Mexico and the United States. Concentrated attention reveals attempts by labor, busi ness, and political groups in both nations to form alliances, but who found themselves eventually ensnared by events in their own nation. The failure to close ranks with one another illuminates the true power of national ambitions and the fitful experiences of potential transnational alliances. With an eye on the larger picture, the rebellion stands as much more than a moment in time when American California was ascendant over Mexican California, or when disturbances in Mexico affected the United States. Through newspaper reports, the statements of labor organiza tions, and the general consensus of national politicians, a study of the 1911 Rebellion can attempt to give all of the above perspectives. An examination of these sources, read by people interested in a conflict far from their homes, presents a picture of how San Francisco’s labor organizations supported social change and justice. They did so in their home city, and throughout the state. In their fight against business leaders, they even addressed the collusion between capital and imperial ism in other countries, such as Mexico. -

Directorio De Oficinas De Recaudación

PUNTOS DE ATENCION A CONTRIBUYENTES La Secretaría de Finanzas y Administración tiene sitios de atención y servicios a contribuyentes y a ciudadanos en todo el territorio del estado y están clasificados de la siguiente manera: 21 Oficinas de recaudación 3 Centros Integrales de Servicios ubicados en: Plaza Galerías, en La Paz Plaza del Sur en Camino Real, en La Paz. Plaza Tamaral en Cabo San Lucas Estos Centros tienen el valor agregado de operar de 8:00 a 16:00 horas de lunes a viernes y los sábados de 10:00 a 14:00 horas, dándole una opción más al contribuyente que no puede acudir entre semana a realizar sus trámites. 4 Módulos de atención ubicados en las instalaciones de las Direcciones de Seguridad y Tránsito Municipal de La Paz, San José del Cabo, Cabo San Lucas y Ciudad Constitución. 10 kioscos de Servicios Electrónicos, ubicados en La Paz, Cabo San Lucas, San José del Cabo y en Ciudad Constitución, los kioscos ofrecen un servicio de siete días a la semana, todo el año, en un horario de 8:00 a 22:00 horas, lo que permite atender en sus días de descanso o en horas inhábiles a aquello contribuyentes que trabajan. Son 9 los servicios que prestan nuestras Oficinas Recaudadoras y Centros Integrales de Servicios: 1. Inscripción en el Registro Estatal de Contribuyentes, 2. Recepción de Pagos de Derechos de Control Vehicular, 3 y 4. Pagos de Impuestos Sobre Nóminas y de Hospedaje, 5. En Materia de Premios y Sorteos, 6. De derechos por servicios prestados por dependencias del ejecutivo, 7. -

Alaska Airlines Files Application to Fly Los Angeles-Havana, Cuba Airline Seeks Governmental Approval to Serve Cuban Capital with Daily Nonstop Service

Alaska Airlines Files Application to Fly Los Angeles-Havana, Cuba Airline seeks governmental approval to serve Cuban capital with daily nonstop service SEATTLE — Alaska Airlines today filed an application with the U.S. Department of Transportation seeking approval to fly two dailynonstop flights from its Latin America gateway of Los Angeles to Havana, Cuba. The Los Angeles metro area has the largest Cuban-American population in the Western United States. “Together with our 14 global partner airlines, Alaska Airlines offers more than 110 nonstop destinations from Los Angeles. As the largest West Coast-based airline, we’re well positioned to offer our customers convenient access to one of the Caribbean’s most popular destinations,” said John Kirby, Alaska Airlines vice president of capacity planning. Citing Alaska's expansive West Coast route structure and low fares, Kirby said Alaska is excited for the opportunity to offer commercial service from the United States to Havana for the first time in over 50 years. With nearly three decades of international service from Los Angeles, Alaska Airlines offers nonstop service to nine destinations in Latin America with the most peak season flights from Los Angeles to popular Mexican resort destinations including Mazatlán, Cabo San Lucas and Puerto Vallarta. Alaska Airlines’ two daytime flights will be attractive to local Los Angeles business, leisure and Cuban American customers, andprovide convenient connecting options for fliers traveling to and from large West Coast cities like Anchorage, Alaska, Portland, Oregon and Seattle. In its application, Alaska is seeking to operate two daily nonstop flights to Havana using a Boeing 737-900ER, which carries 181 passengers in a two-class configuration. -

Cross Border Survey

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents T ABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents. i List of Tables . iii List of Figures. iv Introduction. 1 Motivation for Study . 1 Overview of Methodology . 1 Organization of Report. 3 Acknowledgments . 3 Disclaimer . 3 About True North . 3 Key Findings . 4 Cross-border trips originate close to the border in México.. 4 Trip destinations in the U.S. cluster close to the border. 4 Shopping is the most common reason for crossing the border. 4 The average crosser visits multiple destinations in the U.S. and for a mix of reasons. 4 Most U.S. destinations are reached by driving alone or in a carpool. 5 The typical U.S. visit lasts less than one day. 5 Proximity to the border also shapes U.S. resident trips to México. 5 U.S. residents generally visit México to socialize. 5 The average México visit lasts two days.. 6 Interest in using the Otay Mesa East tolled border crossing was conditioned by several factors. 6 The current study findings are similar to the 2010 study findings . 6 México Resident: U.S. Trip Details. 8 Trip Origin in México . 8 Primary Destination in United States. 10 Primary U.S. Trip Purpose . 10 Duration of U.S. Visit . 12 Miles traveled in U.S. 13 Number of Destinations in the U.S.. 14 Time of Stops in U.S. 14 Duration of Stops in U.S. 18 Location of Destinations in San Diego County. 21 Purpose of Stops in San Diego County . 28 Mode of Travel in San Diego County .