APP202712: an Application to Release the Horsetail Weevil (Grypus Equiseti) As a Biological Control Agent for Field Horsetail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green-Tree Retention and Controlled Burning in Restoration and Conservation of Beetle Diversity in Boreal Forests

Dissertationes Forestales 21 Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Esko Hyvärinen Faculty of Forestry University of Joensuu Academic dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu, for public criticism in auditorium C2 of the University of Joensuu, Yliopistonkatu 4, Joensuu, on 9th June 2006, at 12 o’clock noon. 2 Title: Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Author: Esko Hyvärinen Dissertationes Forestales 21 Supervisors: Prof. Jari Kouki, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Docent Petri Martikainen, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Pre-examiners: Docent Jyrki Muona, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Zoological Museum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Docent Tomas Roslin, Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Division of Population Biology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Prof. Bengt Gunnar Jonsson, Department of Natural Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden ISSN 1795-7389 ISBN-13: 978-951-651-130-9 (PDF) ISBN-10: 951-651-130-9 (PDF) Paper copy printed: Joensuun yliopistopaino, 2006 Publishers: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Finnish Forest Research Institute Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu Editorial Office: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Unioninkatu 40A, 00170 Helsinki, Finland http://www.metla.fi/dissertationes 3 Hyvärinen, Esko 2006. Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests. University of Joensuu, Faculty of Forestry. ABSTRACT The main aim of this thesis was to demonstrate the effects of green-tree retention and controlled burning on beetles (Coleoptera) in order to provide information applicable to the restoration and conservation of beetle species diversity in boreal forests. -

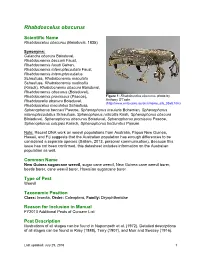

Rhabdoscelus Obscurus

Rhabdoscelus obscurus Scientific Name Rhabdoscelus obscurus (Boisduval, 1835) Synonyms: Calandra obscura Boisduval, Rhabdocnemis beccarii Faust, Rhabdocnemis fausti Gahan, Rhabdocnemis interruptecostata Faust, Rhabdocnemis interruptocostatus Schaufuss, Rhabdocnemis maculata Schaufuss, Rhabdocnemis nudicollis (Kirsch), Rhabdocnemis obscura Boisduval, Rhabdocnemis obscurus (Boisduval), Rhabdocnemis promissus (Pascoe), Figure 1: Rhabdoscelus obscurus, photo by Rhabdoscelis obscura Boisduval, Anthony O'Toole (http://www.ento.csiro.au/aicn/name_s/b_3568.htm) Rhabdoscelus maculatus Schaufuss, Sphenophorus beccarii Pascoe, Sphenophorus insularis Boheman, Sphenophorus interruptecostatus Schaufuss, Sphenophorus nidicollis Kirsh, Sphenophorus obscura BIoisduval, Sphenophorus obscurus Boisduval, Sphenophorus promissus Pascoe, Sphenophorus sulcipes Karsch, Sphenophorus tincturatus Pascoe Note: Recent DNA work on weevil populations from Australia, Papua New Guinea, Hawaii, and Fiji suggests that the Australian population has enough differences to be considered a separate species (Sallam, 2013, personal communication). Because this issue has not been confirmed, this datasheet includes information on the Australian population as well. Common Name New Guinea sugarcane weevil, sugar cane weevil, New Guinea cane weevil borer, beetle borer, cane weevil borer, Hawaiian sugarcane borer Type of Pest Weevil Taxonomic Position Class: Insecta, Order: Coleoptera, Family: Dryophthoridae Reason for Inclusion in Manual FY2013 Additional Pests of Concern List Pest Description Illustrations of all stages can be found in Napompeth et al. (1972). Detailed descriptions of all stages can be found in Riley (1888), Terry (1907), and Muir and Swezey (1916). Last updated: July 29, 2016 1 This species is highly variable in morphology, color, and host preference (reviewed in Giblin-Davis, 2001). 1 Eggs: The eggs of R. obscurus are 1 to 2 mm (approx. /16 in) in length, ivory white in color, and slightly curved (USDA, 1967). -

The Curculionoidea of the Maltese Islands (Central Mediterranean) (Coleoptera)

BULLETIN OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALTA (2010) Vol. 3 : 55-143 The Curculionoidea of the Maltese Islands (Central Mediterranean) (Coleoptera) David MIFSUD1 & Enzo COLONNELLI2 ABSTRACT. The Curculionoidea of the families Anthribidae, Rhynchitidae, Apionidae, Nanophyidae, Brachyceridae, Curculionidae, Erirhinidae, Raymondionymidae, Dryophthoridae and Scolytidae from the Maltese islands are reviewed. A total of 182 species are included, of which the following 51 species represent new records for this archipelago: Araecerus fasciculatus and Noxius curtirostris in Anthribidae; Protapion interjectum and Taeniapion rufulum in Apionidae; Corimalia centromaculata and C. tamarisci in Nanophyidae; Amaurorhinus bewickianus, A. sp. nr. paganettii, Brachypera fallax, B. lunata, B. zoilus, Ceutorhynchus leprieuri, Charagmus gressorius, Coniatus tamarisci, Coniocleonus pseudobliquus, Conorhynchus brevirostris, Cosmobaris alboseriata, C. scolopacea, Derelomus chamaeropis, Echinodera sp. nr. variegata, Hypera sp. nr. tenuirostris, Hypurus bertrandi, Larinus scolymi, Leptolepurus meridionalis, Limobius mixtus, Lixus brevirostris, L. punctiventris, L. vilis, Naupactus cervinus, Otiorhynchus armatus, O. liguricus, Rhamphus oxyacanthae, Rhinusa antirrhini, R. herbarum, R. moroderi, Sharpia rubida, Sibinia femoralis, Smicronyx albosquamosus, S. brevicornis, S. rufipennis, Stenocarus ruficornis, Styphloderes exsculptus, Trichosirocalus centrimacula, Tychius argentatus, T. bicolor, T. pauperculus and T. pusillus in Curculionidae; Sitophilus zeamais and -

Fossil History of Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) from the Paleogene

geosciences Review Fossil History of Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) from the Paleogene Andrei A. Legalov 1,2 1 Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ulitsa Frunze, 11, 630091 Novosibirsk, Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia; [email protected]; Tel.: +7-9139471413 2 Biological Institute, Tomsk State University, Lenin Ave, 36, 634050 Tomsk, Tomsk Oblast, Russia Received: 23 June 2020; Accepted: 4 September 2020; Published: 6 September 2020 Abstract: Currently, some 564 species of Curculionoidea from nine families (Nemonychidae—4, Anthribidae—33, Ithyceridae—3, Belidae—9, Rhynchitidae—41, Attelabidae—3, Brentidae—47, Curculionidae—384, Platypodidae—2, Scolytidae—37) are known from the Paleogene. Twenty-seven species are found in the Paleocene, 442 in the Eocene and 94 in the Oligocene. The greatest diversity of Curculionoidea is described from the Eocene of Europe and North America. The richest faunas are known from Eocene localities, Florissant (177 species), Baltic amber (124 species) and Green River formation (75 species). The family Curculionidae dominates in all Paleogene localities. Weevil species associated with herbaceous vegetation are present in most localities since the middle Paleocene. A list of Curculionoidea species and their distribution by location is presented. Keywords: Coleoptera; Curculionoidea; fossil weevil; faunal structure; Paleocene; Eocene; Oligocene 1. Introduction Research into the biodiversity of the past is very important for understanding the development of life on our planet. Insects are one of the Main components of both extinct and recent ecosystems. Coleoptera occupied a special place in the terrestrial animal biotas of the Mesozoic and Cenozoics, as they are characterized by not only great diversity but also by their ecological specialization. -

Metacommunities and Biodiversity Patterns in Mediterranean Temporary Ponds: the Role of Pond Size, Network Connectivity and Dispersal Mode

METACOMMUNITIES AND BIODIVERSITY PATTERNS IN MEDITERRANEAN TEMPORARY PONDS: THE ROLE OF POND SIZE, NETWORK CONNECTIVITY AND DISPERSAL MODE Irene Tornero Pinilla Per citar o enllaçar aquest document: Para citar o enlazar este documento: Use this url to cite or link to this publication: http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/670096 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement- NoComercial Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence DOCTORAL THESIS Metacommunities and biodiversity patterns in Mediterranean temporary ponds: the role of pond size, network connectivity and dispersal mode Irene Tornero Pinilla 2020 DOCTORAL THESIS Metacommunities and biodiversity patterns in Mediterranean temporary ponds: the role of pond size, network connectivity and dispersal mode IRENE TORNERO PINILLA 2020 DOCTORAL PROGRAMME IN WATER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SUPERVISED BY DR DANI BOIX MASAFRET DR STÉPHANIE GASCÓN GARCIA Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements to obtain the Degree of Doctor at the University of Girona Dr Dani Boix Masafret and Dr Stéphanie Gascón Garcia, from the University of Girona, DECLARE: That the thesis entitled Metacommunities and biodiversity patterns in Mediterranean temporary ponds: the role of pond size, network connectivity and dispersal mode submitted by Irene Tornero Pinilla to obtain a doctoral degree has been completed under our supervision. In witness thereof, we hereby sign this document. Dr Dani Boix Masafret Dr Stéphanie Gascón Garcia Girona, 22nd November 2019 A mi familia Caminante, son tus huellas el camino y nada más; Caminante, no hay camino, se hace camino al andar. -

Arthropods in Linear Elements

Arthropods in linear elements Occurrence, behaviour and conservation management Thesis committee Thesis supervisor: Prof. dr. Karlè V. Sýkora Professor of Ecological Construction and Management of Infrastructure Nature Conservation and Plant Ecology Group Wageningen University Thesis co‐supervisor: Dr. ir. André P. Schaffers Scientific researcher Nature Conservation and Plant Ecology Group Wageningen University Other members: Prof. dr. Dries Bonte Ghent University, Belgium Prof. dr. Hans Van Dyck Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium Prof. dr. Paul F.M. Opdam Wageningen University Prof. dr. Menno Schilthuizen University of Groningen This research was conducted under the auspices of SENSE (School for the Socio‐Economic and Natural Sciences of the Environment) Arthropods in linear elements Occurrence, behaviour and conservation management Jinze Noordijk Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Doctorate Board to be defended in public on Tuesday 3 November 2009 at 1.30 PM in the Aula Noordijk J (2009) Arthropods in linear elements – occurrence, behaviour and conservation management Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen NL with references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978‐90‐8585‐492‐0 C’est une prairie au petit jour, quelque part sur la Terre. Caché sous cette prairie s’étend un monde démesuré, grand comme une planète. Les herbes folles s’y transforment en jungles impénétrables, les cailloux deviennent montagnes et le plus modeste trou d’eau prend les dimensions d’un océan. Nuridsany C & Pérennou M 1996. -

Biodiversity Information Report 27/06/2014

Biodiversity Information Report 27/06/2014 MBB reference: 1060-MEAS Site: South of Whiston Merseyside BioBank, The Local Biodiversity Estate Barn, Court Hey Park Roby Road, Liverpool Records Centre L16 3NA for North Merseyside Tel: 0151 737 4150 [email protected] Your Ref: NA MBB Ref: 1060-MEAS Date: 27/06/2014 Your contact: Roz king MBB Contact: Ben Deed Merseyside BioBank biodiversity information report These are the results of your data request relating to an area at South of Whiston defined by a buffer of 1000 metres around a site described by a boundary you supplied to us (at SJ476902). You have been supplied with the following: • records of protected taxa that intersect the search area • records of BAP taxa that intersect the search area • records of Red Listed taxa that intersect the search area • records of other ‘notable’ taxa that intersect the search area • records of WCA schedule 9 taxa (including ‘invasive plants’) that intersect the search area • a map showing the location of monad and tetrad references that overlap the search area • a list of all designated sites that intersect your search area • citations, where available, for intersecting Local Wildlife Sites • a list of other sites of interest (e.g. Ancient Woodlands) that intersect your search area • a map showing such sites • a list of all BAP habitats which intersect the search area • a map showing BAP habitats • a summary of the area for all available mapped Phase 1 and/or NVC habitats found within 500m of your site • a map showing such habitats Merseyside BioBank (MBB) is the Local Records Centre (LRC) for North Merseyside. -

Marine Insects

UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography Technical Report Title Marine Insects Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pm1485b Author Cheng, Lanna Publication Date 1976 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Marine Insects Edited by LannaCheng Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, La Jolla, Calif. 92093, U.S.A. NORTH-HOLLANDPUBLISHINGCOMPANAY, AMSTERDAM- OXFORD AMERICANELSEVIERPUBLISHINGCOMPANY , NEWYORK © North-Holland Publishing Company - 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior permission of the copyright owner. North-Holland ISBN: 0 7204 0581 5 American Elsevier ISBN: 0444 11213 8 PUBLISHERS: NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY - AMSTERDAM NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY LTD. - OXFORD SOLEDISTRIBUTORSFORTHEU.S.A.ANDCANADA: AMERICAN ELSEVIER PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC . 52 VANDERBILT AVENUE, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10017 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Marine insects. Includes indexes. 1. Insects, Marine. I. Cheng, Lanna. QL463.M25 595.700902 76-17123 ISBN 0-444-11213-8 Preface In a book of this kind, it would be difficult to achieve a uniform treatment for each of the groups of insects discussed. The contents of each chapter generally reflect the special interests of the contributors. Some have presented a detailed taxonomic review of the families concerned; some have referred the readers to standard taxonomic works, in view of the breadth and complexity of the subject concerned, and have concentrated on ecological or physiological aspects; others have chosen to review insects of a specific set of habitats. -

Kalser Dorfertal, Osttirol)

Nationalpark Hohe Tauern Tag der Artenvielfalt 2007 (Kalser Dorfertal, Osttirol) Patrick Gros Wolfgang Dämon Christine Medicus © Patrick Gros - Juli 2007 2007 2 3 Nationalpark Hohe Tauern Tag der Artenvielfalt 2007 (Kalser Dorfertal, Osttirol) Endbericht über die Ergebnisse und Diskussion der erhobenen Daten auf der Basis der Biodiversitätsdatenbank des Nationalparks Hohe Tauern Patrick Gros Wolfgang Dämon Christine Medicus unter Mitarbeit von Heribert Köckinger, Andreas Maletzky, Christian Schröck, Oliver Stöhr, Claudia Taurer-Zeiner, Roman Türk 2007 Gefördert aus Nationalparkmitteln des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft sowie der Länder Salzburg, Kärnten und Tirol. Herausgeber: Haus der Natur Museum für darstellende und angewandte Naturkunde Museumsplatz 5 A-5020 Salzburg, Österreich Auftraggeber: Verein Sekretariat Nationalparkrat Hohe Tauern Kirchplatz 2 A-9971 Matrei in Osttirol, Österreich Zitiervorschlag: GROS, P., DÄMON, W. und MEDICUS C. (2007): Nationalpark Hohe Tauern - Tag der Artenvielfalt 2007 (Kalser Dorfertal, Osttirol). Unveröffentlichter Endbericht im Auftrag des Nationalparks Hohe Tauern. Haus der Natur, Salzburg: 66 Seiten. 4 Inhalt Zusammenfassung ....................................................................................... 5 Einleitung ...................................................................................................... 6 Untersuchungsgebiet .................................................................................... 8 Ergebnis – Übersicht -

ZOOTAXA 63: 1-37 (2002) ISSN 1175-5326 (Print Edition) ZOOTAXA 63 Copyright © 2002 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (Online Edition)

ZOOTAXA 63: 1-37 (2002) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 63 Copyright © 2002 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Addenda and corrigenda to ‘A World Catalogue of Families and Genera of Curculionoidea (Insecta: Coleoptera)’ MIGUEL A. ALONSO-ZARAZAGA1 & CHRISTOPHER.H.C. LYAL2 1Depto. de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2; E-28006 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Omissions from and corrections to Alonso Zarazaga & Lyal (1999) are given. The following 19 valid taxa described before 2000 were absent and are now included: Brarus Kuschel, 1997 in Nem- onychidae, Brachycorynus, Habroxenus, Neoxenus, Sicanthus and Trigonorhinini (all of Valentine, 1999 in Anthribidae), Gobicar Gratshev & Zherikhin, 1999 in Eccoptarthridae, Neoicaris Hoff- mann, 1968 in Erirhinidae, Baezia Alonso-Zarazaga & García, 1999, Ecezius Thompson, 1982, Hirtegrius Colonnelli, 1999, Kyklioacalles Stueben, 1999, Neasphalmus Nakane, 1963, Neomrocz- kowskiella Kania, 1999, Notegrius Colonnelli, 1999, Onyxacalles Stueben, 1999, Oreochorus Zaslavskij & Korotyaev, 1998, Perigasteromimus Colonnelli, 1999, Pseudoglyptobaris Thompson, 1982 and Strophocodes Pelletier, 1999 in Curculionidae. A new replacement name is proposed in Attelabidae: Riedeliops Alonso-Zarazaga & Lyal (subgenus of Euops Schoenherr, 1839) nom. nov. for Charops Riedel, 1998 (non Holmgren, 1858). New synonymies are: Basitropini Lacordaire, 1866 (= Eugonini Lacordaire, 1866, syn. nov.) in Anthribidae; Haplorhynchites (Haplorhynchites) Voss, 1924 (= Aphlorhynchites Sawada, 1993, syn. nov., removed from synonymy with Teretrio- rhynchites) in Rhynchitidae; Belorhynchus Berthold, 1827 (= Belopherus Schoenherr, 1833, syn. nov.) and Arrhenodini Lacordaire, 1866 (= Belorhynchini Lacordaire, 1866, syn. -

(Insecta, Coleoptera) В Фауне Арктики. Сообщение 1

ЗООЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ЖУРНАЛ, 2014, том 93, № 1, с. 7–44 ЭКОЛОГИЯ И ЗООГЕОГРАФИЯ УДК 595.76 ОТРЯД ЖЕСТКОКРЫЛЫХ (INSECTA, COLEOPTERA) В ФАУНЕ АРКТИКИ. СООБЩЕНИЕ 1. СОСТАВ ФАУНЫ © 2014 г. Ю. И. Чернов1, О. Л. Макарова1, Л. Д. Пенев2, О. А. Хрулёва1 1 Институт проблем экологии и эволюции им. А.Н. Северцова РАН, Москва 119071, Россия e(mail: [email protected] e(mail: oa([email protected] 2 Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, София, Болгария e(mail: [email protected] Поступила в редакцию 01.09.2013 г. Жесткокрылые, крупнейший отряд насекомых, в условиях Арктики уступают двукрылым первен ство в полноте освоения среды. На долю Coleoptera приходится около 13% энтомофауны тундровой зоны, однако несколько семейств жуков сохраняют в высоких широтах значительное видовое раз нообразие и существенную ценотическую роль. В этом сообщении мы даем обзор циркумполярной колеоптерофауны Арктики. На основе оригинальных данных, литературных сведений и фондовых коллекционных материалов с использованием экстраполяций и аналогий отмечены особенности таксономического и экологического разнообразия подотрядов, серий и семейств Coleoptera, про анализированы широтнозональное распределение и северные пределы распространения видов, специфика адаптаций и ценотических связей. Ключевые слова: Арктика, жуки, природная зональность, видовое разнообразие, ареал, адаптации. DOI: 10.7868/S004451341401005X Жесткокрылые (Coleoptera) – самый крупный основных широтных трендов параметров их раз отряд насекомых, включающий почти 386500 ви нообразия. дов (Slipinski et al., 2011). На его долю приходится Накопленные к настоящему времени данные почти 40% видов класса. Доминирование этого свидетельствуют о том, что в фауне Арктики на отряда в энтомофауне наиболее отчетливо в теп долю жесткокрылых приходится около 13% видо лых поясах, в тропиках и субтропиках. В умерен вого богатства насекомых, в северной полосе ном поясе жесткокрылые составляют треть видо тундровой зоны их доля снижается до 4%, а в по вого богатства насекомых. -

Glasgow's Water Beetles

The Glasgow Naturalist (online 2012) Volume 25, Part 4. Urban biodiversity: Successes and Challenges Urban Biodiversity: Successes and Challenges: Glasgow’s water beetles Garth N. Foster The Aquatic Coleoptera Conservation Trust, 3 Eglinton Terrace, Ayr KA7 1JJ E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION the list of 101 species recorded from 1990 onwards. Water beetles are a well-recorded freshwater group in However several water beetles specialising in pond Britain despite lacking the charisma of dragonflies and habitats have become established in the Glasgow area the angling interest of mayflies and the like. The over a similar period. conference on urban biodiversity held by the Glasgow Natural History Society in October 2010 provided the The following examples of some species in decline and stimulus to assess their status in the area. some on the increase serve to illustrate the range of habitats that can be occupied. Water beetles cannot be precisely excised from beetles Noterus clavicornis (De Geer) This species is usually as a whole. Coleoptera are divided into two major referred to as “The Large Noterus” because the name groups, the Adephaga and the Polyphaga. Within the clavicornis has also been applied to the smaller, Adephaga the name “Hydradephaga” has been coined flightless N. crassicornis (Müller), which is very rare to distinguish diving beetles and related species from in Scotland. The earliest Scottish record is a little the ground beetles in the Carabidae. This works fairly uncertain but by 1946 N. clavicornis was in the garden well so long as one ignores the fact that many ground of the greatest proponent of water beetles, Frank beetles are confined to aquatic emergent vegetation or Balfour-Browne, in Dumfriesshire and it was first to the water’s edge.