Fourth Annual Italian Madrigal Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

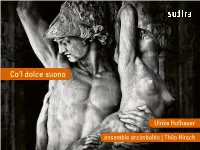

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Trecento Cacce and the Entrance of the Second Voice

1 MIT Student Trecento Cacce and the Entrance of the Second Voice Most school children today know the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and could probably even explain how to sing it as a canon. Canons did not start off accessible to all young children, however. Thomas Marrocco explains that the early canons, cacce, were not for all people “for the music was too refined, too florid, and rhythmically intricate, to be sung with any degree of competence by provincial or itinerant musicians.”1 The challenge in composing a caccia is trying to create a melody that works as a canon. Canons today (think of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” Pachelbel's “Canon in D,” or “Frère Jacques”) are characterized by phrases which are four or eight beats long, and thus the second voice in modern popular canons enters after either four or eight beats. One might hypothesize that trecento cacce follow a similar pattern with the second voice entering after the first voice's four or eight breves, or at least after the first complete phrase. This is not the case. The factors which determine the entrance of the second voice in trecento cacce are very different from the factors which influence that entrance in modern canons. In trecento cacce, the entrance of the second voice generally occurs after the first voice has sung a lengthy melismatic line which descends down a fifth from its initial pitch. The interval between the two voices at the point where the second voice enters is generally a fifth, and this is usually just before the end of the textual phrase in the first voice so that the phrases do not line up. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Multiple Choice

Unit 4: Renaissance Practice Test 1. The Renaissance may be described as an age of A. the “rebirth” of human creativity B. curiosity and individualism C. exploration and adventure D. all of the above 2. The dominant intellectual movement of the Renaissance was called A. paganism B. feudalism C. classicism D. humanism 3. The intellectual movement called humanism A. treated the Madonna as a childlike unearthly creature B. focused on human life and its accomplishments C. condemned any remnant of pagan antiquity D. focused on the afterlife in heaven and hell 4. The Renaissance in music occurred between A. 1000 and 1150 B. 1150 and 1450 C. 1450 and 1600 D. 1600 and 1750 5. Which of the following statements is not true of the Renaissance? A. Musical activity gradually shifted from the church to the court. B. The Catholic church was even more powerful in the Renaissance than during the Middle Ages. C. Every educated person was expected to be trained in music. D. Education was considered a status symbol by aristocrats and the upper middle class. 6. Many prominent Renaissance composers, who held important posts all over Europe, came from an area known at that time as A. England B. Spain C. Flanders D. Scandinavia 7. Which of the following statements is not true of Renaissance music? A. The Renaissance period is sometimes called “the golden age” of a cappella choral music because the music did not need instrumental accompaniment. B. The texture of Renaissance music is chiefly polyphonic. C. Instrumental music became more important than vocal music during the Renaissance. -

Madrigal, Lauda, and Local Style in Trecento Florence

Madrigal, Lauda, and Local Style in Trecento Florence BLAKE McD. WILSON I T he flowering of vernacular traditions in the arts of fourteenth-century Italy, as well as the phenomenal vitality of Italian music in later centuries, tempts us to scan the trecento for the earliest signs of distinctly Italianate styles of music. But while the 137 cultivation of indigenous poetic genres of madrigal and caccia, ac- corded polyphonic settings, seems to reflect Dante's exaltation of Italian vernacular poetry, the music itself presents us with a more culturally refracted view. At the chronological extremes of the four- teenth century, musical developments in trecento Italy appear to have been shaped by the more international traditions and tastes associated with courtly and scholastic milieux, which often combined to form a conduit for the influence of French artistic polyphony. During the latter third of the century both forces gained strength in Florentine society, and corresponding shifts among Italian patrons favored the importation of French literary and musical culture.' The cultivation of the polyphonic ballata after ca. 1370 by Landini and his contem- poraries was coupled with the adoption of three-part texture from French secular music, and the appropriation of certain French nota- tional procedures that facilitated a greater emphasis on syncopation, Volume XV * Number 2 * Spring 1997 The Journal of Musicology ? 1997 by the Regents of the University of California On the shift in patronage and musical style during the late trecento, see Michael P. Long, "Francesco Landini and the Florentine Cultural Elite," Early Music History 3 (1983), 83-99, and James Haar, Essays on Italian Poetry and Music in the Renaissance, 1350-1600 (Berkeley, CA, 1986), 22-36. -

Opera Origins

OPERA ORIGINS l)y ERt^^A LOUISE BOLAN B. A. , Ottawa University, 1952 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Departirient of Kusic KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1968 _o Approved l^:. ih*-^ .-_-c^ LiacZ Major I^ofesst^ ii /^^ - . BG^' table of contents Page ^^^ INTRODUCTIOII • Chapter I. THE FOK^'S OF MUSICAL DRM^A BEFORE 1594 1 LITURGICAL DRill^^A 1 MYSTERIES 3 SECUL.AR DR/U'lATIC MUSIC 5 6 Masche):ata , Masque , and Ballet Intei-ir.edio " Madrigal Forras H Pastoral e Drama • 12 II. THE EMERGENCE OF OPERA THROUGH THE ZiWM^k 15 - 17 . MONODY THE GREEK WAY DAFNE 25 EURIDICE 27 MOKTETORDI AND ORFEO 31 ACKT>IOV.?LEDGl'ni;NT 33 BIBLICGRAPHI 34 INTRODUCTION In trying to reconstruct and assess the main features of any historical event, it is difficiilt to find the starting point. The history of opera is no exception. We find varying degrees of impor- tance given certain events by different v/riters. We find va-iters who see the music and drama combination of the Middle Ages and the Renais- sance as seeds of opera, and others feeling there is no significant connection. Ho\rever, in the inindo of the members of the "Florentine Caraerata," long since recognized as the originators of opera, there v;as no doubt as to the origin of their idea. Creek trsigedy, as they under- stood it, was the sole basis of their experiments. And yet, little is knovm of the part music really played in Greek drama, the one extant example being a very short mutilated fragment of imison melody from a chorus of Euripides' Orestes (^^08 b.c), and even this was not knovm to the early opera composers. -

Revisiting the Origins of the Italian Madrigal Using Machine Learning

Revisiting the Origins of the Italian Madrigal (with machine learning) Julie E. Cumming Cory McKay Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference Maynooth, Ireland, July 6, 2018 1 The origins of the madrigal Current consensus • The madrigal emerges as a new genre of Italian-texted vocal music in the 1520s • The Italian-texted works by Verdelot are madrigals • It originated in Florence (and Rome?) in the 1520s But where did it come from? • The frottola (Einstein 1949) • The chanson and motet (Fenlon and Haar 1988) • Florentine song: carnival song, and improvised solo song (A. Cummings 2004) 2 Finding the origins: what happened before Verdelot? • Verdelot arrived in Florence in 1521 • Earliest sources of the madrigal New focus: Florence, 1515-1522 Music Printsbefore Verdelot Thanks to I. Fenlon, J. Haar, and A. Cummings Naming of Genres: Canzona in 1520s; Madrigale 1530 Prints (in or near Rome) • Pisano, Musica sopra le Canzone del petrarcha (partbooks, Petrucci, Fossombrone, 1520) (all Madrigals) • Motetti e Canzone I (partbooks, Rome, 1520) • Libro primo de la croce, choirbook, c. 1522 (surviving copy, later ed., Rome, Pasoti & Dorico, 1526) • Mix of frottole, villotte, and madrigals 4 Music MSS before Verdelot Thanks to I. Fenlon, J. Haar, and A. Cummings Florentine Manuscripts (all from Florence) • Florence, Basevi 2440, choirbook, c. 1515-22; 2 sections: • music with multiple stanzas of text (frottole) • through-composed works (madrigals & villotte) • Florence, BNC 164-167, partbooks, c. 1520-22 (4 sections) • Florence 164 or F 164 henceforth 5 My hypothesis The madrigal was deliberately created as a • high-style genre of secular music • that emulates the style of the motet Why? • Musical sources • Texts • Musical style • Cultural context (not today) 6 What do sources tell us? Madrigals are the first secular genre to be treated like Latin-texted motets in prints and manuscripts Copied and printed in partbooks (previously used only for Masses and motets) • Motetti e Canzone I (Rome, 1520), partbooks • Florence 164 (c. -

ACET Junior Academies'

ACET Junior Academies’ Scheme of Work for music Year 5 Unit 1.1: A Musical Masque About this unit: This unit of work is linked to the History scheme of work HT 1.1 Post 1066 Study: The Tudors. It is a starting point for exploration into Tudor music. In it children will begin to learn about Tudor Dance music, in particular the Pavan as a popular Tudor dance. Children will identify its characteristic musical features and rhythms before attempting to dance the Pavan and performing their own Pavan melody over a drone accompaniment. Children will then move on to learn about traditional Tudor musical instruments before exploring Tudor songs and madrigal-style songs with a ‘fa, la, la, la’ refrain. Where they will compose their own lyrics to a madrigal melody. Fanfares are explored briefly before children work towards putting on a Tudor style banquet/concert combining elements of all the musical learning in to a class performance. Unit structure National Curriculum objectives: This unit is structured around six sequential music enquiries: 1. What is a Pavan? Links to previous and future National Curriculum 2. How do we perform a Pavan? units/objectives 3. What do Tudor instruments sound like? KS2 4. What is a Madrigal? ● Listen with attention to detail and recall sound with 5. What is a Fanfare? increasing aural memory. BBC Ten Pieces 6. A musical masque – banquet/concert. ● Appreciate and understand a wide range of high-quality live and recorded music drawn from different traditions and from great composers and musicians. ● Play and perform in solo ensemble contexts, using their voices and playing musical instruments with increasing accuracy, fluency, control and expression. -

Une Jeune Pucelle 3’43 Se Chante Sur « Une Jeune Fillette »

menu tracklist texte en français text in english textes chantés / lyrics AU SAINCT NAU 1 Procession Conditor alme syderum 2’40 2 Procession Conditor le jour de Noel 1’20 Se chante sur « Conditor alme syderum » 3 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°4 sur Conditor alme syderum 1’48 (Orgue seul) 4 Jean Mouton - Noe noe psallite noe 3’21 5 Jacques Arcadelt - Missa Noe noe, Kyrie 8’06 Alterné avec le Kyrie « le jour de noël », qui se chante sur Kyrie fons bonitatis 6 Clément Janequin - Il estoyt une fillette 3’01 Se chante sur « Il estoit une fillette » 7 Anonyme/Christianus de Hollande Plaisir n’ay plus que vivre en desconfort 4’03 Se chante sur « Plaisir n’ay plus » 8 Claudin de Sermizy Dison Nau à pleine teste 3’27 Se chante sur « Il est jour, dist l’alouette » 9 Claudin de Sermizy - Au bois de deuil 3’49 Se chante sur « Au joly boys » 10 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°31 sur Une jeune fillette 1’48 (Orgue seul) 3 11 Loyset Pieton O beata infantia 8’20 12 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°30 sur Une jeune fillette 1’37 (Orgue seul) 13 Eustache Du Caurroy Une jeune pucelle 3’43 Se chante sur « Une jeune fillette » 14 Guillaume Costeley - Allons gay bergiere 1’37 15 Claudin de Sermizy L’on sonne une cloche 3’35 Se chante sur « Harri bourriquet » 16 Anonyme - O gras tondus 1’42 17 Claudin de Sermizy Vous perdez temps heretiques infames 2’16 Se chante sur « Vous perdez temps de me dire mal d’elle » 18 Claude Goudimel Esprit divins, chantons dans la nuit sainte 2’16 Se chante sur « Estans assis aux rives aquatiques » (Ps.