Conϐlict Studies Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sub-Centre Status of Balangir District

SUB-CENTRE STATUS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT Sl No. Name of the Block Name of the CHC Name of Sector Name of PHC(N) Sl No. Name of Subcenter 1 Agalpur 1 Agalpur MC 2 2 Babupali 3 3 Nagaon 4 4 Rengali 5 5 Rinbachan 6 Salebhata Salebhata PHC(N) 6 Badtika 7 7 Bakti CHC 8 AGALPUR 8 Bendra Agalpur 9 9 Salebhata 10 10 Kutasingha 11 Roth Roth PHC(N) 11 Bharsuja 12 Dudka PHC(N) 12 Duduka 13 13 Jharnipali 14 14 Roth 15 15 Uparbahal 1 Sindhekela 16 Alanda 2 Sindhekela 17 Arsatula 3 Sindhekela 18 Sindhekela MC 4 Sindhekela 19 Dedgaon 5 Bangomunda Bangomunda PHC(N) 20 Bangomunda 6 Bangomunda Bhalumunda PHC(N) 21 Bhalumunda 7 Bangomunda Belpara PHC(N) 22 Khaira CHC 8 BANGOMUNDA Bangomunda 23 Khujenbahal Sindhekela 9 Chandotora 24 Batharla 10 Chandotora 25 Bhuslad 11 Chandotora 26 Chandutara 12 Chandotora 27 Tureikela 13 Chulifunka 28 Biripali 14 Chulifunka Chuliphunka PHC(N) 29 Chuliphunka 15 Chulifunka 30 Jharial 16 Chulifunka 31 Munda padar 1 Gambhari 32 Bagdor 2 Gambhari 33 Ghagurli 3 Gambhari Gambhari OH 34 Ghambhari 4 Gambhari 35 Kandhenjhula 5 Belpada 36 Belpara MC 6 Belpada 37 Dunguripali 7 Belpada 38 Kapani 8 Belpada 39 Nunhad 9 Mandal 40 Khairmal CHC 10 BELPARA Mandal Khalipathar PHC(N) 41 Khalipatar Belpara 11 Mandal 42 Madhyapur 12 Mandal Mandal PHC(N) 43 Mandal 13 Mandal 44 Dhumabhata 14 Mandal Sulekela PHC(N) 45 Sulekela 15 Salandi 46 Bahabal 16 Salandi 47 Banmal 17 Salandi 48 Salandi 18 Salandi 49 Sarmuhan 19 Salandi 50 Kanut 1 Chudapali 51 Barapudugia 2 Chudapali Bhundimuhan PHC(N) 52 Bhundimuhan 3 Chudapali 53 Chudapali MC 4 Chudapali 54 -

Maternal Mortality in Orissa: an Epidemiological Study My

a!Ç9wb

Y Report (Dsr) of Balangir District, Odisha

Page | 1 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF BALANGIR DISTRICT, ODISHA. FOR ROAD METAL/BUILDING STONE/BLACK STONE (FOR PLANNING & EXPLOITATION OF MINOR MINERAL RESOURCES) ODISHA BALANGIR As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi dated 25th July 2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (MoEF & CC) COLLECTORATE BALANGIR Page | 2 CONTENT CH. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. NO. Preamble 4-5 1 Introduction 1.1 Location and Geographical Area 6-9 1.2 Administrative Units 9-10 1.3 Connectivity 10-13 2 Overview of Mining Activity in the District 13 3 General Profile of the District 3.1 Demography 14 4 Geology of the District 4.1 Physiography & Geomorphology 15-22 4.2 Soil 22-23 4.3 Mineral Resources. 23-24 5 Drainage of Irrigation Pattern 5.1 River System 25 6 Land Utilization Pattern in the District 6.1 Forest and non forest land. 26-27 6.2 Agricultural land. 27 6.3 Horticultural land. 27 7 Surface Water and Ground Water Scenario of the District 7.1 Hydrogeology. 28 7.2 Depth to water level. 28-30 7.3 Ground Water Quality. 30 7.4 Ground Water Development. 31 7.5 Ground water related issues & problems. 31 7.6 Mass Awareness Campaign on Water Management 31 Training Programme by CGWB 7.7 Area Notified By CGWB/SGWA 31 7.8 Recommendations 32 8 Rainfall of the District and Climate Condition 8.1 Month Wise rainfall. 32-33 8.2 Climate. 33-34 9 Details of Mining Lease in the District 9.1 List of Mines in operation in the District 34 Page | 4 PREAMBLE Balangir is a city and municipality, the headquarters of Balangir district in the state of Odisha, India. -

Town and Village Directory, Bolangir, Part-A, Series-16, Orissa

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1971 SERIES 16 ORISSA PART X DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOO~ PART A-TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY BOLANGIR B. TRIPATHI of- the Indian Administrative Service Director Df Census Operations, Orissa CENSUS OF INDIA, 1971 DISTRICT CENSUS HA-NDBOOK PART A-TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY BOLA_NGIR PREFACE The District Census Handbook first introduced.as an ancillary to 1951 Census appeared as a State. Government publication in a more elaborate and ambitious form in 1961 Census. It was divided into 3 parts: Part] gave a narrative account of each District; Part 1I contained various Census Tables and a ~eries of Primary Census data relating to each village and town ; and Part III presented certain administrative statistics obtained from Government Departments. These parts further enriched by inclusion of maps of the district and of police stations within the district were together -brought out in ODe volume. The Handbook, for each one of the 13 Districts of the State was acknowledged to be highly useful. 2. But the purpose and utility of this valuable compilation somewhat suffered on account of the time lag that intervened between the conclusion of Census and the publication of the Handbook. The delay was unavoidable in the sense that the Handbook-complete with all the constituent parts brought together in one volume had necessarily<to wait till after completion of the processing and tabulation of Gensus data and collection and compilation of a large array of administrative and other statistics. 3. With the object of cutting out the delay, and also_ to making each volume handy and not-too-bulky it has been decided to bring out the 1971 District Census Handbook in three parts separately with the data becoming available from stage to stage as briefly indicated below : Part A-This part will incorporate the Town Directory and the Village Directory for each district. -

40423-053: Due Diligence of Ongoing Projects in Assam, Chhattisgarh

Due Diligence Report on Social Safeguards April 2015 IND: Rural Connectivity Investment Program – Project 3 Due Diligence of Ongoing Projects in Assam, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and West Bengal under Project 1 and Project 2 (Loan 2881-IND) and (Ln 3065-IND) Prepared by Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 March 2015) Currency unit – Indian rupees (INR/Rs) Rs1.00 = $ 0.016 $1.00 = Rs 62.5096 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADB : Asian Development Bank APs : Affected Persons BPL : Below Poverty Line CD : Cross Drainage DM : District Magistrate EA : Executing Agency EAF : Environment Assessment Framework ECOP : Environmental Codes of Practice FFA : Framework Financing Agreement GOI : Government of India GRC : Grievances Redressal Committee IA : Implementing Agency IEE : Initial Environmental Examination MFF : Multi-Project Financing Facility MORD : Ministry of Rural Development MOU : Memorandum of Understanding NC : Not Connected NGO : Non-Government Organization NRRDA : National Rural Road Development Agency NREGP : National Rural Employment Guarantee Program PIU : Project Implementation Unit PIC : Project Implementation Consultants PFR : Periodic Finance Request PMGSY : Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana RCIP : Rural Connectivity Investment Programme ROW : Right-of-Way RRP : Report and Recommendation of the President RRSIP II : Rural Roads Sector II Investment Program SRRDA : State Rural Road Development Agency ST : Scheduled Tribes TA : Technical Assistance TOR : Terms of Reference TSC : Technical Support Consultants UG : Upgradation WHH : Women Headed Households GLOSSARY Affected Persons (APs): Affected persons are people (households) who stand to lose, as a consequence of a project, all or part of their physical and non-physical assets, irrespective of legal or ownership titles. -

Environmental Monitoring Report

Environmental Monitoring Report Semiannual Monitoring Report April – September 2017 July 2018 IND: Railway Sector Investment Program Prepared by Ministry of Railways for the Government of India and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Indian Government Ministry of Railways Asian Development Bank Multitranche Financing Facility No. 0060-IND Loan No. 2793-IND, 3108-IND Railway Sector Investment Program Track Doubling and Electrification on Critical Routes Environmental Monitoring Report Semi Annual Report: April 2017 – September 2017 Egis Rail – Egis India Environmental Safeguards Monitoring Report No. 9 September 2017 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Background ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Railway Sector Investment Programme and Multi Tranche Financing Facility ...................... 3 1.2 Active contracts -

ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No

OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION :ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No:-458(syllabus)/ Date19.07.2017 In pursuance of the Notification No-19724/SME, Dated-28.09.2016 of the Govt. of Odisha, School & Mass Education Deptt. & Letter No-1038/Plg, Dated-19.06.2017 of the State Project Director, OMSM/RMSA, the Vocational Education Course under RMSA at Secondary School Level in Trades i.e. 1.IT & ITES, 2.Travel & Tourism & 3.Retail will continue as such in Class-IX for the Academic session-2017-18 and 4.BFS (In place of B.F.S.I) , 5.Beauty & Wellness and 6. Health Care will be introduced newly in Class-IX(Level- I ) for the Academic Session- 2017-18 as compulsory subject in the following 208(old) & 106(new) selected Schools (Subject mentioned against each).The above subjects shall be the alternative of the existing 3rd language subjects . The students may Opt. either one of the Third Languages or Vocational subject as per their choice. The period of distribution shall be as that of Third Language Subjects i.e. 04 period per week so as to complete 200 hours of course of Level-I . The course curriculum shall be at par with the curriculum offered by PSSCIVE, Bhopal . List of 314 schools (208 + 106) approved under Vocational Education (2017-18) under RMSA . 208 (Old Schools) Sl. Name of the Approval Name of Schools UDISE Code Trade 1 Trade 2 No. District Phase PANCHAGARH BIJAY K. HS, 1 ANGUL 21150303103 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism BANARPAL 2 ANGUL CHHENDIPADA High School 21150405104 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 3 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR High School 21150606501 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism MAHENDRA High School, 4 ANGUL 21151001201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism ATHAMALLIK 5 ANGUL MAHATAB High School 21150718201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 6 ANGUL PABITRA MOHAN High School 21150516502 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 7 ANGUL JUBARAJ High School 21151101303 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 8 ANGUL Anugul High School 21150902201 Phase I IT/ITeS 9 BALANGIR GOVT. -

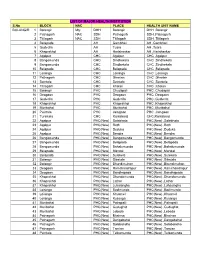

LIST of MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTION S.No BLOCK NAC

LIST OF MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTION S.No BLOCK NAC PLACE HEALTH UNIT NAME BOLANGIR 1 Bolangir Mty DHH Bolangir DHH ,Bolangir 2 Patnagarh NAC SDH Patnagarh SDH ,Patnagarh 3 Titilagarh NAC SDH Titilagarh SDH ,Titilagarh 4 Belapada AH Gambhari AH ,Gambhari 5 Gudvella AH Tusra AH ,Tusra 6 Khaprakhol AH Harishankar AH ,Harishankar 7 Agalpur CHC Agalpur CHC ,Agalpur 8 Bangomunda CHC Sindhekela CHC ,Sindhekela 9 Bangomunda CHC Sindhekela CHC ,Sindhekela 10 Belapada CHC Belapada CHC ,Belapada 11 Loisinga CHC Loisinga CHC ,Loisinga 12 Patnagarh CHC Gharian CHC ,Gharian 13 Saintala CHC Saintala CHC ,Saintala 14 Titilagarh CHC Kholan CHC ,Kholan 15 Bolangir PHC Chudapali PHC ,Chudapali 16 Deogaon PHC Deogaon PHC ,Deogaon 17 Gudvella PHC Gudvella PHC ,Gudvella 18 Khaprakhol PHC Khaprakhol PHC ,Khaprakhol 19 Muribahal PHC Muribahal PHC ,Muribahal 20 Puintala PHC Jamgaon PHC ,Jamgaon 21 Tureikela CHC Kantabanji CHC,Kantabanji 22 Agalpur PHC(New) Salebhata PHC(New) ,Salebhata 23 Agalpur PHC(New) Roth PHC(New) ,Roth 24 Agalpur PHC(New) Duduka PHC(New) ,Duduka 25 Agalpur PHC(New) Bendra PHC(New) ,Bendra 26 Bangomunda PHC(New) Bangomunda PHC(New) ,Bangomunda 27 Bangomunda PHC(New) Belapada PHC(New) ,Belapada 28 Bangomunda PHC(New) Bahalumunda PHC(New) ,Bahalumunda 29 Belapada PHC(New) Mandal PHC(New) ,Mandal 30 Belapada PHC(New) Sulekela PHC(New) ,Sulekela 31 Bolangir PHC(New) Sibatala PHC(New) ,Sibatala 32 Bolangir PHC(New) Bhundimuhan PHC(New) ,Bhundimuhan 33 Deogaon PHC(New) Ramchandrapur PHC(New) ,Ramchandrapur 34 Deogaon PHC(New) Bandhapada PHC(New) -

Government of Odisha Panchayat Samiti, Agalpur

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA PANCHA Y A T S A M I T I , AGALPUR DISTRICT: BOLANGIR, ODISHA - 767061 DRAFT TENDER SCHEDULE Name of Work: Const. of RCC Culvert at Guhiramunda to Rengali road Value of Work: Rs.5,87,978.00 ( Rupees Five Lakhs Eighty Seven Thousand Nine hundred Seventy Eight Only) Head of Account : BIJUKBK(State Sector) 2015-16 Block Dev. Officer, Agalpur P a g e | 1 APPROVED TENDER SCHEDULE TENDER CALL NOTICE NO: - 01/APR/2016-17 of Panchayat Samiti, Agalpur Name of Work: Const. of RCC culvert at Guhiramunda to Rengali road. Value of Work (Amount put to tender) : Rs.5,87,978.00 /- Head of Account: : BIJUKBK(State Sector) 2015-16 E.M.D. required : Rs. 6,000/- Class of contractor : “D” & “C” Cost of tender paper including 5%VAT : Rs. 4,200/- Period of completion : 3 Calendar months Last date of sale of tender paper : Dt. 26/04/2016 up to 1.00 PM Last date of receipt of tender paper : Dt.26/04/2016 up to 1.00 PM Date & time of opening of tender paper : Dt.27/04/2016 at 11.30 AM The tender documents contain 24 (Twenty Four) pages only. Block Dev. Officer RECORD OF SALE OF TENDER DOCUMENTS CONTRACTOR Block Dev. Officer, Agalpur P a g e | 2 Name of Work : : Const. of RCC Culvert at Guhiramunda to Rengali road. 1. Tender Call Notice No : TENDER CALL NOTICE NO:- 01/APR/2016-17 of Panchayat Samiti, Agalpur 2. Name, class & address of the Contractor : ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _______________ 3. -

Bolangir, Odisha - 767061

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA PANCHAYAT SAMITI, AGALPUR DISTRICT: BOLANGIR, ODISHA - 767061 TENDER SCHEDULE Name of Work: Const. of BDO Quarter(1no) & staff quarter (2Nos) at Agalpur Block Premises. Value of Work: Rs 31,22,822(Rupees Thirty one Lakhs Twenty two Thousand eight hundred twenty two Only) Head of Account : 4th SFC(2018-19) Block Dev. Officer, Agalpur Page | 1 APPROVED TENDER SCHEDULE TENDER CALL NOTICE NO: - 01/APR/2018-19 of Panchayat Samiti, Agalpur Name of Work: Const. of BDO Quarter(1No) & Staff Quarter (2Nos) at Agalpur Block Premises Value of Work (Amount put to tender) : Rs.31,22,822/- th Head of Account: : 4 SFC(2018-19) E.M.D. required : Rs. 31,300/- Class of contractor : “C” & “B” Cost of tender paper : Rs. 6,000/- Period of completion : 12 Calendar months Last date of sale of tender paper : Dt. 13.03.2019 up to 1.00 PM Last date of receipt of tender paper : Dt.13.03.2019 up to 2.00 PM Date & time of opening of tender paper : Dt.13.03.2019 at 3.30 PM The tender documents contain 25 (Twenty five) pages only. Block Dev. Officer CONTRACTOR Block Dev. Officer, Agalpur Page | 2 RECORD OF SALE OF TENDER DOCUMENTS Name of Work : : Const. of BDO quarter(1No)& staff quarter(2Nos) at Block Premises 1. Tender Call Notice No : TENDER CALL NOTICE NO:- 01/APR/2018-19 of Panchayat Samiti, Agalpur 2. Name, class & address of the Contractor : ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _______________ 3. Registering Authority with validity period. : _______________________________________ 5. Date of application : ________________________________________ 6. -

Agro-Economic Research Centre

DROUGHTDROUGHT VULNERABILITY,VULNERABILITY, COPINGCOPING CAPACITYCAPACITY ANDAND RESIDUALRESIDUAL RISK:EVIDENCERISK:EVIDENCE FROMFROM BOLANGIRBOLANGIR DISTRICTDISTRICT ININ ODISHAODISHA Dr Mrutyunjay Swain Research Officer (Economics) Agro-Economic Research Centre Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat, India IntroductionIntroduction Understanding Drought Vulnerability and Risk The complex process of climate change affects the vulnerable populations, livelihoods and different sectors through a rise in frequency and intensity of CINDs (IPCC, 2007). Drought is the most complex and least understood among all CINDs, affecting more people than any other hazards. Drought Planning and Mitigation One of the main aspects of any drought mitigation and planning is the ‘vulnerability assessment’ (Wilhelmi et al 2002). Vulnerability assessment requires the identification of who and what are most vulnerable and why. 2 Objectives • To analyze the observed impacts of the climate change and recurrent droughts in Bolangir district of Orissa. • To assess the nature and determinants of drought risk and vulnerability experienced by selected blocks of drought prone study region. • To critically examine the relative influence of different socioeconomic and biophysical factors to the levels of drought vulnerability in the study region. • To suggest some policy measures to reduce the extent of drought vulnerability and risk in the study region.3 DataData andand MethodologyMethodology Multistage Sampling Method First stage: Bolangir district was -

Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan

Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan: Towards Agricultural Development in Aspirational Districts Editors Kalyan Sundar Das Shyamal Kumar Mondal Suddhasuchi Das Sati Shankar Singh ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute Kolkata Indian Council of Agricultural Research Bhumi Vihar Complex, Block- GB, Sector-III Salt Lake, Kolkata- 700097 (West Bengal) ICAR-ATARI KOLKATA Citation Das K S, Mondal S K, Das S and Singh S S. 2020.Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan: Towards agricultural development in Aspirational Districts. ICAR- Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute Kolkata, West Bengal, India, pp: 1-126. Compiled and Edited by Dr. K. S. Das Dr. S. K. Mondal Dr. S. Das Dr. S. S. Singh Contributed by KVK Bolangir, Odisha KVK Dhenkanal, Odisha KVK Gajapati, Odisha KVK Kalahandi, Odisha KVK Kandhamal, Odisha KVK Koraput, Odisha KVK Malkangiri, Odisha KVK Nabarangpur, Odisha KVK Nuapada, Odisha KVK Rayagada, Odisha Technical Assistance by Mr. S. Khutia, DEO, ICAR-ATARI Kolkata Published by Dr. S. S. Singh Director, ICAR-ATARI Kolkata Printed at Semaphore Technologies Pvt. Ltd., 3, Gokul Baral Street, Kolkata-700012, #+91-9836873211 Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan Hkkjrh; d`f”k vuqla/kku ifj”kn d`f”k vuqla/kku Hkou&1] iwlk] ubZfnYyh 110 012 INDIAN COUNCIL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH Krishi Anusandhan Bhawan, Pusa, New Delhi – 110 012 Ph.:91-11-25843277 (O), Fax : 91-11-25842968 Mk- v’kksd dqekj flag E-mail: [email protected] mi-egkfuns’kd (d`f”k izlkj) Dr. A.K. Singh Deputy Director General (Agricultural Extension) Message It gives me immense pleasure to learn that ICAR-Agricultural Technology Application Research Institute, Kolkata has come up with a compilation of various multi-faceted agricultural activities undertaken during Krishi Kalyan Abhiyan (1st June 2018 to 15th April 2019).