Above the Falls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost in Coos

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

Tsunami Inundation Map for Coos

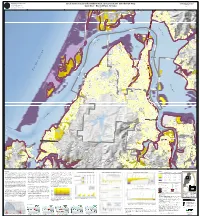

G E O L O G Y F A N O D STATE OF OREGON T Tsunami Inundation Map Coos-05 N M I E N DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES M E T R R A Tsunami Inundation Maps for Coos Bay - North Bend, A www. OregonGeology.org L Local Source (Cascadia Subduction Zone) Tsunami Inundation Map P I E Coos County, Oregon N D D Larry Givens, Governing Board Chair U N S O T Vicki S. McConnell, Director and State Geologist G R E Plate 1 I R E S O Don WT. Lewis, Assistant Director Coos Bay - North Bend, Oregon Rachel R. Lyles Smith, Project Operations Manager 2012 1937 Ian P. Madin, Chief Scientist 124°20'0"W 124°18'0"W 124°16'0"W 124°14'0"W 124°12'0"W L N TRANS-PACIFIC LN I C I F C A R O B I N R D - P 43°26'0"N S N D A R R T E V O C N N N L A D D OV E R W O J 100 S W A L L O W R D E A ! S T B A Y R D North Bay RFPD M Jordan A L L A R D L N Cove 43°26'0"N ¤£101 R O S E M T N L N 100 C o o 25 City of North Bend "7 s E . C . R D B "5 M C C L U R G L N 200 a 100 y 25 EAST BAY RD y L N E E City of North Bend S a R U O B C City of Coos Bay G O L F D s F E R R Y R o ¤£101 E V C A A o City of Coos Bay R L S O R R N P 25 H O R T S I S 100 M C N L I N A R I O North W R Pony E S P V E E A O Bend A I R R ! L P 100 T Fire N O Slough W R SHERMAN AVE T W E I L A V N Y Y A B 200 L O O P C O L O R A D O A V E O O D City of North Bend A R B AY S T O M L A O P C L E L E A F F S T F L O R I D A A V E M A P L E S T H AY E S S T A R T H U R S T J O H N S O N S T M O N TA N A A V E D C O N N E C T I C U T A V E T R S ¤£101 L L W E D A X A M E MCPHERSON AVE H U N I O N A V E L -

Coos Bay BCS Number: 47-8

Coos Bay BCS number: 47-8 ***NOTE: The completion of this site description is still in progress by our Primary Contact (listed below). However, if you would like to contribute additional information to this description, please contact the Klamath Bird Observatory at [email protected]. Site description author(s) Jennifer Powers Danielle Morris, Research and Monitoring Team, Klamath Bird Observatory Primary contact for this site Mike Graybill, South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve Manager. Telephone: 541-888-5558 ext. 24, e-mail: [email protected]. Site location (UTM) Datum: NAD83, Zone: 10, Easting: 394143, Northing: 4802686 General description The Coos Bay estuary covers 54 square miles of open channels and tide flats located near the towns of the Coos Bay and North Bend on the southern Oregon coast. The estuary ranges between a mile and a mile and a half wide. A 42 ft. deep, sixteen-mile long ship channel is maintained from the harbor entrance to the Port of Coos Bay. Numerous slough systems and freshwater channels flow into Coos Bay. The narrow estuary is maintained at its mouth by two rock jetties extending from North Spit on the north and Coos Head on the south. From the harbor entrance the main channel bears northward past the communities of Charleston, Barview and Empire, then east around the city of North Bend, and south past downtown Coos Bay. At Coos Bay the channel bears east to the mouth of the Coos River. About two miles upstream the river divides into the Millicoma River on the left and the South Fork of the Coos River on the right. -

AN INVENTORY of MARITIME ANTIQUES and RELICS of the COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS of a SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST by Gail E. Curtis Or

AN INVENTORY OF MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS OF THE COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS OF A SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST By Gail E. Curtis Oregon Institute of Marine Biology Summer, 1975 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ,INTRODUCTION 1 - EXPLANATIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS 6 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE INVENTORIED COLLECTIONS 7 MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS 17 BOAT NAME PLATES 28 HALF MODELS 29 MARITIME LITERATURE 31 MARITIME MAPS, CHARTS, AND DRAWINGS 35 MARITIME PHOTOGRAPHS 39 LIFE SAVING STATION General History 75 LIFES SAVINGS CREW, STATION AND EQUIPMENT PHOTOGRAPHS.. 76 CAPE ARAGO LIGHTHOUSE PHOTOGRAPHS 78 JETTY CONSTRUCTIONS PHOTOGRAPHS BO EARLY MARSHFIELD PHOTOGRAPHS 83 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Victor West 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 92 DISTRIBUTION LIST 93 INTRODUCTION Coos Bay has always been tied to the sea. From the rich estuarys earliest settlement in the 1830s, its lines of supply Ind communication have been with the sea rather than the hinter- land across the Coast Range Mountains. Even as late as 1915 when the railroad came to southwestern Dregon, the sea, the bay, and the rivers of the Coos Bay region represented the main forms of coastwise trade with California and the inter-community trade from the farms and lumber camps of the interior to the urban market areas of Marshfield (Coos Bay) and later North Bend. In some respects,modern Coos Bay remains even more tied to the sea than in the past. Emerging as a major port of international trade, mainly through the export of its forest products, Coos Bays leaders recognize their communitys future fortune lies with the sea, for a form of transportation, an important food supply, and a desirable periphery for a living environment. -

Bandon Hatchery

BANDON HATCHERY PROGRAM MANAGEMENT PLAN 2020 Bandon Hatchery (Beaver Creek, Big Creek Pond, Blossom, Charleston, Cunningham Creek, Coquille, Eel Creek, Ferry Creek, Hodges, Laverne Park, Millicoma Pond, Morgan Creek, Noble Creek, Saunders, Sevenmile Creek, Tenmile and Woodward Creek Acclimation Sites) INTRODUCTION Bandon Hatchery is located one mile east of the City of Bandon. The site is at an elevation of approximately 98 feet above sea level, at latitude 43.1161 and longitude -124.3842. Total land area is 32.7 acres. The hatchery water supply is obtained from two sources: Ferry Creek and Geiger Creek. Water from both sources is supplied by gravity. Starting on October 13, 2017, 3.5 cfs was transferred to the hatchery in which 2.5 was dedicated for fish production and 1 cfs for instream rights. This now gives the hatchery a combined total of 5.5 cfs. The facility is staffed with 3.0 FTE's. Rearing Facilities at Bandon Hatchery Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Number Total Construction Type Length Width Depth Volume Units Volume Material Age Condition Comment (ft) (ft) (ft) (ft3) (ft3) Adult Holding Pond 80 20 3.25 5200 1 5200 concrete 1950 poor spawning building built over first 20' of pond Raceway 120 20 3.5 8400 1 8400 concrete 1950 fair Raceway 110 20 3.67 8074 1 8074 concrete 1950 fair Raceway 50 20 5.5 5500 1 5500 concrete 1937 poor used for settling pond for vacuum sludge Raceway 45 15 2.5 1688 1 1688 concrete 1950 good Raceway 100 20 3.5 7000 1 7000 concrete 1950 poor used as acclimation ponds Raceways 100 20 3.5 7000 2 14000 concrete 1958 good Troughs 16 3.2 2 102 2 205 concrete 1958 fair Troughs 16.75’ 2.2 3 110.55 2 221.1 fiberglass 2018 excellent Troughs 16 2.5 1.33 53 4 213 fiberglass 1991 good Vertical incubators 448 2003 excellent 28 stacks of 16 trays PURPOSE Bandon Hatchery was constructed in 1925 and facility operations are funded by the State of Oregon. -

Middle Fork Coquille Watershed Analysis Was Because of Riparian Reserve Density Management Treatments Proposed in the Slater Rocks EA

WATERSHED ANALYSIS MIDDLE FORK COQUILLE ANALYTICAL WATERSHED Version 1.1 Bureau of Land Management Coos Bay District Myrtlewood Resource Area October 2007 Approved by: ___________________________________ Myrtlewood Area Manager Note to reader: The reason for the second version (version 1.1) of the Middle Fork Coquille Watershed Analysis was because of Riparian Reserve density management treatments proposed in the Slater Rocks EA. Density management in Riparian Reserves was added to this Watershed Analysis as Issue 10: Density Management Treatments within Riparian Reserves. TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary......................................................................1 Introduction.................................................................5 Description of the Middle Fork Coquille Analytical Watershed.................7 Table 1. Land Ownership, basin area, and stream miles.......................7 Beneficial Uses/Values.......................................................8 Land Allocations.............................................................9 Table 2. BLM Land Allocations..............................................12 Fig. 1: Location of Coquille River in Oregon...............................13 Fig. 2: Coquille River Basin with Key Watersheds...........................14 Issues Evaluated in the Analysis............................................15 Issue 1: Native Fish Stocks................................................15 Issue 2: Riparian Condition................................................18 Issue 3: Aquatic Habitat...................................................21 -

The Coquille River Basin, Southwestern Oregon

Preliminary Assessment of Channel Stability and Bed-Material Transport in the Coquille River Basin, Southwestern Oregon By Krista L. Jones, Jim E. O’Connor, Mackenzie K. Keith, Joseph F. Mangano, and J. Rose Wallick Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Oregon Department of State Lands Open-File Report 2012–1064 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: South Fork Coquille River in the Broadbent Reach (Photograph by Krista L. Jones, U.S. Geological Survey, July 2010.) Preliminary Assessment of Channel Stability and Bed-Material Transport in the Coquille River Basin, Southwestern Oregon By Krista L. Jones, Jim E. O’Connor, Mackenzie K. Keith, Joseph F. Mangano, and J. Rose Wallick Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Oregon Department of State Lands Open-File Report 2012–1064 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.govFor more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Jones, K.L., O’Connor, J.E., Keith, M.K., Mangano, J.F., and Wallick, J.R., 2012, Preliminary assessment of channel stability and bed-material transport in the Coquille River basin, southwestern Oregon: U.S. -

State Waterway Navigability Determination

BODY OF WATER & LOCATION NAV CG NON-NAV CG REMARKS yellow highlight = apply to USCG for permit up to RM stipulated Alsea Bay, OR X Estuary of Pacific Ocean. Alsea River, OR X Flows into Alsea Bay, Waldport, OR. Navigable to mile 13. Ash Creek, OR X Tributary of Willamette River at Independence, OR. Barrett Slough, OR X Tributary of Lewis and Clark River. Bayou St. John, OR X Court decision, 1935 AMC 594, 10 Mile Lake, Coos County, OR. Bear Creek (Coos County), OR X Tributary of Coquille River (tidal at mile 0.5) Beaver Creek, OR X Tributary of Nestucca River. Beaver Slough, OR X See Clatskanie River. Big Creek (Lane County), OR X At U.S. 101 bridge (tidal). Big Creek (Lincoln County), OR X Flows into Pacific Ocean. Big Creek Slough, OR X Upstream end at Knappa, OR (tidal). At site of Birch Creek (Sparks) Bridge on Canyon Road near Birch Creek, OR X Pendleton, OR. Side channel of Yaquina River. 3 mi. downstream from Toledo, Blind Slough, OR X OR (tidal). Tributary of Knappa Slough. 10 mi. upstream from Astoria, OR Blind Slough/ Gnat Creek, OR X (tidal at mile 2.0). Boone Slough, OR X Tributary of Yaquina River between Newport and Toledo, OR. Side channel of Willamette River. 3 miles upstream from Booneville Channel, OR X Corvallis, OR. Boulder Creek, OR X 7 miles N of Lake Quinalt. Side channel of Columbia River. 5 miles N of Clatskanie, OR Bradbury Slough, OR X (tidal). Brownlee Reservoir, ID /OR X See Snake River. Also known as South Channel. -

Coos River Paddling

OREGON SOUTH COAST COOS RIVER PADDLING The spirit of Oregon South Coast flows through its waterways, sharing Fed by more than two dozen freshwater tributaries and spread over nearly common characteristics, offering similar bounties, yet each one distinct. 20 square miles, Coos Bay is the largest estuary on the Oregon South Coast, Whether finding their sources high in the Cascades, like the Umpqua and offering a variety of year round paddling opportunities. Ride the tides up Rogue, or rising from the rugged Coast Range, like the Coos, Coquille and sloughs and inlets, launch expeditions along the working waterfronts and Chetco, the rivers play a vital role, from wildlife and fish habitat to early- around bay islands, or explore the peaceful reaches of Sough National day transportation corridor and sport-fishing destination. For local tribes, Estuarine Research Reserve, the nation’s first protected estuary. “everything was about the river,” and this profound connection is still very Estuaries are protected embayments where rivers meet the sea. They support much a part of their culture. Today the rivers also enjoy a growing popularity a fascinating tapestry of life – from worms, clams and other tiny creatures with paddlers who have discovered these little-visited gems of Oregon South buried deep in the mud, to multitudes of young fish and crabs, to dozens of Coast. species of resident and migratory birds. Parts of Rogue and Chetco are federally-designated Wild and Scenic Rivers, In addition to its many natural attractions, the area has a rich and colorful and the Umpqua, Coos and Coquille flow into wide-ranging estuaries as they history, with fascinating remnants of the early pioneer days, as well as traces of near the sea, with inlets, sloughs, channels and quiet back waters to explore. -

Winter Steelhead Fishing in Oregon's Umpqua, Coos and Coquille Rivers

Winter Steelhead Fishing in Oregonʼs Umpqua, Coos and Coquille Rivers 4/22/18, 1242 AM Custom Search BestFishingInAmerica.com Share Best Fishing in Oregon Home Winter Steelhead on the South-Central Best of Oregon Coast: Coos, Coquille and Umpqua Oregon Map Rivers About Us Southwestern Oregon’s rivers are known for excellent fishing for winter steelhead, a rainbow trout that fattens in the ocean like a salmon before returning to rivers from late fall through winter to spawn. Photo courtesy of Big K Ranch's Guide Service The following rivers (listed north to south) are the best spots in Douglas and Coos counties in the Oregon Shop New Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Southwest Zone. For Yamaha Sport rivers at the southern end of this zone, see Best Winter Boats Steelhead Fishing on Oregon’s South Coast. Also, for a look at some of the lesser-known and smaller winter steelhead fisheries in the zone, including some with wild fish harvest, try: Small Winter Steelhead Streams in Southwest Oregon. Umpqua River The Umpqua has plenty of fishing options – from huge You might also like these articles: salmon, sturgeon and striped bass to feisty smallmouth bass and shad. It also has tons of steelhead that run almost Best Winter Steelhead Fishing on the every month of the year. Rogue and Southern Oregon Coast Best Fishing in Oregon's Southwest Zone (Umpqua and Coos Bay Area) The mainstem can produce huge catches, as in 2006-07 Best Fishing in Oregon's Southwest Zone when nearly 4,200 fish were harvested. The previous few (Rogue and South Coast Rivers) Best Summer Steelhead Fishing on the seasons saw retention above 2,300, according to ODFW Oregon Coast catch records, but then fishing was pretty tough for a few years. -

Some Recent Physical Changes of the Oregon Coast

rOREGON STATE UNIVERS TY LIBRARIES IIIIII 111IIIII1 IIII III 12 0002098016 65458 .8 05 cop .3 FINAL RE PORT (Report on an investigation carried out under Contract Nonr-2771 (04), Project NR 388-062, between the University of Oregon and the Office of Naval Research, U. S. Department of the Navy.) Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted for any purpose of the United States Government. SOME RECENT PHYSICAL CHANGES OF THE OREGON COAST by Samuel N. Dicken assisted by Carl L. Johannessen and Bill Hanneson Department of Geography University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon November 15, 1961 Reprinted in the public interest by the EugeneRegister-Guard and the Lane County Geographical Society,Inc., April, 1976. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The subject of coastal changes is of interest to many people living on or near the Oregon coast and, as a result, numerous interviews, only a few of which can be acknowledged, furnished much information not otherwise available. Valuable assistance came from persons concerned professionally with some aspect of coastal change. The staff of the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Portland District, was most helpful, especially H. A. Kidby of the Rivers and Harbors Section, Lloyd Ruff of the Geology Section, Mr. Charles Oros of the Photogrammetry Office and Dorothy McKean, Librarian. Mr. E. Olson of the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey located copies of old charts and other materials.Ralph Mason of the Oregon State Department of Geology and Mineral Industriescon- tributed notes on Ecola Park and other areas. Robert L. Brown and the staff of the U. S. Soil Conservation Service furnished photographs andspec- ific information on vegetation changes of the dunes.Park Snavely of the U. -

Coos County, Oregon, Is Located in the South- Western Part of the State on the Pacific Slope

COOS COUNTY OREGON ITS RESOURCES, INDUSTRIES AND OPPORTUNITIES COOS COUNTY SCENES Silver Falls, Coos River 2. Gasoline Craft on Coos River. 3. Golden Falls, Coos River. 4. Scene on Coos Bay Watron Roau. PUBLICATION AUTHORIZED BY (oos County Chamber of Commerce and the County Court FOR DISTRIBUTION AT THE Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition 1909 PRESS OP COOS BAY HARBOR. NORTH BEND. OREGON GASOLINE BOATS 1. A Pleasure Jaunt up Coos River. 2. A Passenger Boai. 3. The Wil- helmina. Bancton to Coos Bay. 4. The Bonita" on Her Regular Run 5 The "Eagle" Making 12 Knots. COOS COUINTY ITS RESOURCES AND INDUSTRIES OOS COUNTY, Oregon, is a part of the United States which C offers especially good inducements to those who live in other localities and are seeking a place to settle on the great Pacific coast, the country's sunset land of plenty and promise. Oregon is known as a state of opportunity but in no part will there be found more chances than in Coos county. There is room for many industries and thousands of people and there is much development to be done. The developers will reap the benefit. Whether mechanic, farmer, investor or business man, the opportunity for the newcomer exists because the county is rich in natural resources, because the time has come for the development of what nature has endowed, because the point has been reached where the more rapid growth will come and because of the destiny of Coos county to be one of the important points of the western coast. Favorable Location.