A Methodological Approach to the Identification of Duck and Goose Remains from Archaeological Sites with an Application to Roman Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Systematic Position of the Ring-Necked Duck

460 Hollister, Ring-necked Duck. [o"t. into consideration the evanescence of the diagnostic markings, and the inaccessibility of the coastal marshes where the bird breeds, together with the fact that the few ornithologists who seem to have visited them were generally armed only with cameras, it is perhaps not so odd after all. In assembling the data upon which these notes are based, besides those already mentioned, to whom I am particularly indebted, my thanks are due to Messrs. Stanley C. Arthur, O. Bangs, Howarth S. Boyle, William Brewster, Jonathan Dwight, J. H. Flemming, Harry C. Oberholser, Wilfred H. Osgood, T. S. Palmer, H. S. Swarth, P. A. Taverner, W. E. Clyde Todd, and John E. Thayer. THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE RING-NECKED DUCK. BY N. HOLLISTER. The group of fuliguline Ducks now called Marila in the American ' Ornithologists' Union Check-List ' has had its full share of nomen- clatorial shifts and changes, and many schemes have been proposed for its division into genera or subgenera. It has always seemed to me that the question of the number and rank of the named super- specific sections within this group is of little importance in com- parison to the error involved in the sequence given the species in the ' Check-List,' where the Canvasback is placed between the Redhead and the Scaups, and the Ring-necked Duck is put at the end of the series in the typical subgenus Marila. From a study of the literature of American Ducks it is evident that the belief prevails that the Ring-necked Duck (Marila col- laris) is a Scaup, very closely related to the Greater and Lesser Bluebills (Marila marila and M. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

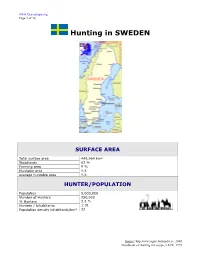

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Notes on Scaup X Tufted Duck Hybrids by Bryan L

Notes on Scaup x Tufted Duck hybrids By Bryan L. Sage (Plates 6 and 7b) SINCE THE LENGTHY controversy over the 'Lesser Scaup' problem, which was finally settled by Perrins (1961), most field ornithologists have been alive to the occasional occurrence of hybrid ducks. Hybrids of various parentages are very frequent in the Anatidae, both in captivity and to an unknown but possibly quite considerable extent in the wild. In addition to individuals of wild origin, many of the hybrids bred in captivity are left full-winged and frequently take to a feral existence. The most aggravating aspect of the whole problem to the field worker is the almost total lack of descriptions and illustrations of these hybrids in the normal identification books. The object of this short paper, therefore, is to give as much information as possible about two hybrids, one drake and one duck, bred in captivity from a male Scaup {Aythya marila) and a female Tufted Duck {A. fuliguld), to compare them with other recorded hybrids between these two species, and to see what conclusions can be reached about the field-characters of this cross. The emphasis is very much on the drake, partly because I am now fortunate enough to have the skin as a study specimen and partly because most of the other records refer to males; in any case, females would be very difficult to identify in the field. PLUMAGE DESCRIPTION OF A MALE SCAUP X TUFTED DUCK HYBRID This drake hybrid and the female discussed later on were, as already mentioned, the progeny of a male Scaup and a female Tufted Duck. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION THE ROLE OF DOMESTIC DUCKS IN THE MAINTENANCE AND SPREAD OF AVIAN INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN INDONESIA Submitted by Kristy L. Pabilonia Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Richard Bowen Tawfik Aboellail Doreene Hyatt Anthony Knight ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF DOMESTIC DUCKS IN THE MAINTENANCE AND SPREAD OF AVIAN INFLUENZA VIRUSES IN INDONESIA Wild waterfowl and aquatic birds serve as the natural reservoir host for influenza A viruses. As the reservoir, wild waterfowl play an important role in the persistence and transmission of influenza viruses among bird populations and to other mammalian species. In many Asian countries, domestic ducks are raised for meat and egg production. Some of these domestic ducks are ranged on rice paddies or post-harvest rice fields. The ducks provide service to the rice fields by fertilizing the field with feces and aerating the field by swimming and walking through the ground cover. Additionally, the ducks serve as a form of insect control through their natural grazing behaviors. The role that domestic ducks play in the ecology of influenza viruses is poorly understood. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus (HPAI H5N1) originated in Guangdong Province, China in 1996, which was followed by global dissemination of the virus that began in 2003. This virus is unprecedented in geographical spread, economic consequences and public health significance. At the present time, HPAI H5N1 virus is endemic six countries, including Indonesia. Indonesia has experienced the highest incidence of human infections with HPAI H5N1 virus and one of the highest case fatality rates. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Further Notes on the Tufted Duck in St. James's Park, London

FURTHER NOTES ON THE TUFTED DUCK IN ST. JAMES'S PARK, LONDON By E. H. GILLHAM INTRODUCTION THIS PAPER on Tufted Duck (Ay thy a fuligula) in St. James's Park deals primarily with observations for 1956 and 1957. In addition, however, certain information gained during the previous three years, 1953-55, is summarized for the first time with the comparable details for 1956-57, and the general picture of events outlined in a previous paper (Gillham, 1957) is brought up to date. As in previous years, observations were made between late April and early October as follows : — On 90 days (twice in a day on 24) in the 140-day period 18th May-sth October 1956. On 128 days (twice in a day on 39) in the 171-day period 23rd April-ioth October 1957. During both breeding-seasons visits were regular, averaging on 4 days out of 7 in 1956 and on 5 days out of 7 in 1957. Daily counts, and the close scrutiny of birds at the various feeding points, as outlined previously (Gillham, op. cit.), were continued throughout both years. For almost the entire 1957 breeding-season, the construction of two widely-spaced parallel dams, with a drained pit between for bridge-building, divided' the lake into two separate waters. This was of great assistance to counting and observation for, apart from the movement or attempted movement of several newly-hatched Tufted broods from one portion to the other, there was no other passage of families or of independent ducklings between the Horse Guards end and Palace end lakes. -

TUFTED DUCK Aythya Fuligula Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional Winterer Monotypic

TUFTED DUCK Aythya fuligula non-breeding visitor, occasional winterer monotypic Tufted Ducks breed across the n. Palearctic and winter S to n. Africa, India, and the Philippine Is (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1952, Cramp and Simmons 1977). They are regular vagrants to N America (AOU 1998, CBRC 2007) and rare winter visitors to the Hawaiian Islands, with records rather equally distributed between the Northwestern and Southeastern Islands. Records also occur from throughout Micronesia E to the Marshall Is (Clapp 1990), and possibly Wake Atoll (Rauzon et al. 2008). In contrast to the two scaup species and Ring-necked Duck, there is little evidence that individual Tufted Ducks return to Hawaii for consecutive winters, although two adults at Kuilima STP, O'ahu in 2010-2011 could have been among the 5 there in 2009-2010. Most records of Tufted Ducks from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are from Midway, where 10 specimens were collected between 1959 and 1980 (USNM; Fisher 1960, Clapp and Woodward 1968, Engilis et al. 2004) and 8 additional birds were observed in 1963-2002 (e.g., Fisher 1965; HRBP 0345, 1262-1264). At least 7 present during the winter of 1963 (Clapp and Woodward 1968) represents the high count. Other records from the Northwest Islands are from Kure (5, 1963-2011; e.g., USNM 493448, 497908; HRBP 6703-6704) and French Frigate (1, 17-19 Nov 1984; HRBP 0572-0574, 0792). The earliest fall arrival was recorded 25 Oct (1965, Midway) and of several that wintered on Midway in 1995-2002, the latest individual remained until early Apr (2000). -

Proteomic Analysis of 1-D Sarcoplasmic Protein Profiles of Pekin Duck Embryos’ Pectoralis Muscle As Influenced by Incubation Temperature

Proteomic analysis of 1-D Sarcoplasmic Protein Profiles of Pekin Duck Embryos’ Pectoralis Muscle as Influenced by Incubation Temperature THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Yang Cheng Graduate Program in Animal Sciences The Ohio State University 2014 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Michael Lilburn, Advisor Dr. MacDonald Wick Dr. William Pope Copyrighted by Yang Cheng 2014 Abstract The objective of this study was to identify sarcoplasmic proteins responsive to incubation temperature in Pekin duck embryos. Previous studies reported that a 1-degree Celsius increase in incubation temperature during the first 10 days can accelerate embryonic development and this study was designed to identify the effects of early incubation temperature on embryonic myogenesis. Pekin duck eggs were incubated at 37.5 ͦC or 38.5 ͦC for the first ten days and subsequently transferred to 37.5 ͦC for the rest of incubation (ED 11-28). The embryonic pectoralis muscle (PM) was collected at ED12, 18, 25 and hatch and sarcoplasmic proteins were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Gels were digitized into TotalLabTM to acquire the mean band percentage (MBP) of bands. The body weight (BW) of embryos and pectoralis muscle weight (PMW) of the Pekin duck embryos were analyzed in SAS 9.3. An acceleration in BW at ED12 in the 38.5 ͦC treatment was observed but not at later ages. MIXED model is performed to determine bands responding significantly to incubation temperature. Three proteins/bands are determined to significantly respond to temperature. -

SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Aythya Fuligula

SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET Aythya fuligula English name: Scientific name: Tufted duck Aythya fuligula Taxonomical group: Species authority: Class: Aves Linnaeus, 1758 Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Subspecies, Variations, Synonyms: – Generation length: 5 years Past and current threats (Habitats Directive Future threats (Habitats Directive article 17 article 17 codes): Other threat factors (declining codes): Other threat factors (declining colonies of colonies of L. ridibundus; J03.01), Tourism L. ridibundus; J03.01), Tourism (G01, G02), Alien (disturbance; G01, G02), Alien species (I01), species (I01), Competition and predation (I02), Competition and predation (I02), Hunting Hunting (F03.01), Bycatch (F03.02.05), Oil spills (F03.01), Bycatch (F03.02.05), Oil spills (H03.01) (H03.01) IUCN Criteria: HELCOM Red List NT A2ab Category: Near Threatened Global / European IUCN Red List Category Annex I EU Birds Directive-no LC / LC Annex II EU Birds Directive-II A Red List status in HELCOM countries: Denmark: LC, Estonia: LC, Finland: VU, Germany: * (*Not threatened), Latvia: –, Lithuania: –, Poland: – , Russia: –, Sweden: LC Range description and general trends The tufted duck is a widespread breeder across much of Europe. The European population counts >730 000 bp. Although the species was stable or increased in much of its range during 1990–2000, there were declines in north-eastern Europe, including the north-eastern Baltic Sea. Aythya fuligula. Photo by Lutz Ritzel. Distribution and status in the Baltic Sea region The size of the breeding population is much smaller in the western Baltic Sea area than in the north- eastern parts of the region. The Swedish population has been stable both in short-term and long-term (Ottvall et al. -

Welfare Assessment for Captive Anseriformes: a Guide for Practitioners and Animal Keepers

animals Article Welfare Assessment for Captive Anseriformes: A Guide for Practitioners and Animal Keepers Paul Rose 1,2,* and Michelle O’Brien 2 1 Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour, Psychology, Washington Singer, University of Exeter, Perry Road, Exeter EX4 4QG, UK 2 Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge Wetland Centre, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 May 2020; Accepted: 1 July 2020; Published: 3 July 2020 Simple Summary: Zoological collections are constantly working to find new ways of improving their standards of care for the animals they keep. Many species kept in zoos are also found in private animal collections. The knowledge gained from studying these zoo-housed populations can also benefit private animal keepers and their animals. Waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans) are examples of species commonly kept in zoos, and in private establishments, that have received little attention when it comes to understanding their core needs in captivity. Measuring welfare (how the animal is coping with the environment that it is in) is one way of understanding whether a bird’s needs are being met by the care provided to it. This paper provides a method for measuring the welfare of waterfowl that can be applied to zoo-housed birds as well as to those in private facilities. The output of such a welfare measurement method can be used to show where animal care is good (and should be continued at a high standard) and to identify areas where animal care is not meeting the bird’s needs and hence should be altered or enhanced to be more suitable for the birds being kept. -

Raising Ducks

, . , RAISING DUCKS UNITED STATES FARMERS' PREPARED BY DEPARTMENT OF BULLETIN SCIENCE AND G AGRICULTURE NUMBER 2215 EDUCATION ADMINISTRATION CONTENTS Breeds _________ ______ _____ ____________ ______ ____ _ PAOli I ~eat b~8 ______ ___ ____ ___ _____ __ _______ __ _ _ I Egg-producingbreeds ______________________ __ __ 3 Breeding stock. ___ ____ ___ _____ _____________ ______ _ 4 Selection of breeders. _______ __________ ___ ____ _ _ 4 Breeder (acilities ___ _____ ___ ____ __ ______ __ ____ _ _ 4 EggXli~ucuon---- --- - - ---- --- -- --- --- -------- 5 HaD g eggs __ ____________________ __ ___ _____ _ 5 Incubation __ ___ __ _______ _____ ___ _______ _______ ____ 6 Artificial incuba.tion __ _____ __ . _. ___ • ______ .. __ . __ 6 Natural incubation. ____ __ • __ ____ _ . ___ ___._ . __ _ 8 Brooding and rearing __ __ ____ ______ _____ ____ __ ___ __ _ NuUition _______________ ____ _____ ____________ __ __ _ 8 10 ~arketing ____ _______________ __ ________ __ __ ______ _ II Diseases ______ ___ ______ ___ ____ ___ _____ __ __• __ ___ __ 13 lasued Mareh 1966 Slightly revi8ed AllgU/It 1969 W!l!!hington, D,C, Approved for reprinting September 1976 For ~ale by tho SU()(lrintondont of Doeumenlli, U.S, Government Printing Office Wa!hlnlton, O.C.!lru02 Stock No. 001-000-00070-6 11 RAISING DUCKS By William J. Ash, Department ot Biology, St. T..uwren(!c Uni\'crsity, Canton, N.Y. 13617' The number of ducks raised an are marketed through supply nually for meat in the United States houses and retail grocery outlets.