Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration Chronology of Waterfowl in the Southern High Plains of Texas

Migration Chronology of Waterfowl in the Southern High Plains of Texas LAURA BAAR1,2, RAYMOND S. MATLACK1,3, WILLIAM P. JOHNSON4 AND RAYMOND B. BARRON1 1Department of Life, Earth and Environmental Sciences, West Texas A&M University, Box 60808, Canyon, TX 79016-0001 2Current address: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, P.O.Box 226, Karnack, TX 75661 3Corresponding author; Internet: [email protected] 4Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, P.O. Box 659, Canyon, TX 79015 Abstract.—Migration chronology was quantified for 15 waterfowl species on 58 playa wetlands in the Southern High Plains of Texas from February 2004 through April 2006. Abundance of each species was estimated on playas once every two weeks during the nonbreeding season (16 August to 30 April); presence of ice was also recorded. Dabbling ducks were most common (N = 250,668) and most tended to exhibit either a bimodal migration pattern (lower abundance in winter than during fall and spring passage) or a unimodal pattern (one defined peak). Abun- dance of the most common dabbling ducks was skewed toward late winter and spring. Most species of diving ducks (N = 15,128) tended to exhibit irregular migration patterns. Canada Geese (both Branta canadensis and B. hutchinsii, N = 15,347) had an abundance pattern that gradually increased, peaking in midwinter, and then decreased, which is typical for a terminal wintering area. Ice was most common on playas during the first half of December, which coincided with the lowest winter abundance in dabbling ducks. Data from this study will support management ef- forts focused on playa wetlands, including the development of population goals and habitat objectives that span the entire non-breeding season. -

Supplementary Material

Aythya ferina (Common Pochard) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 6 Sources of reported national population data p. 9 Species factsheet bibliography p. 17 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Aythya ferina (Common Pochard) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population trend4 -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Aythyini (Pochards) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Aythyini (Pochards)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 13. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Aythyini (Pochards) Drawing on preceding page: Canvasback (Schonwetter, 1960) to 1,360 g (Ali & Ripley, Pink-headed Duck 1968). Eggs: 44 x 41 mm, white, 45 g. Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham) 1790 Identification and field marks. Length 24" (60 em). Other vernacular names. None in general English Adult males have a bright pink head, which is use. Rosenkopfente (German); canard a tete rose slightly tufted behind, the color extending down the (French); pato de cabeza rosada (Spanish). hind neck, while the foreneck, breast, underparts, and upperparts are brownish black, except for some Subspecies and range. No subspecies recognized. Ex pale pinkish markings on the mantle, scapulars, and tinct; previously resident in northern India, prob breast. -

The Systematic Position of the Ring-Necked Duck

460 Hollister, Ring-necked Duck. [o"t. into consideration the evanescence of the diagnostic markings, and the inaccessibility of the coastal marshes where the bird breeds, together with the fact that the few ornithologists who seem to have visited them were generally armed only with cameras, it is perhaps not so odd after all. In assembling the data upon which these notes are based, besides those already mentioned, to whom I am particularly indebted, my thanks are due to Messrs. Stanley C. Arthur, O. Bangs, Howarth S. Boyle, William Brewster, Jonathan Dwight, J. H. Flemming, Harry C. Oberholser, Wilfred H. Osgood, T. S. Palmer, H. S. Swarth, P. A. Taverner, W. E. Clyde Todd, and John E. Thayer. THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE RING-NECKED DUCK. BY N. HOLLISTER. The group of fuliguline Ducks now called Marila in the American ' Ornithologists' Union Check-List ' has had its full share of nomen- clatorial shifts and changes, and many schemes have been proposed for its division into genera or subgenera. It has always seemed to me that the question of the number and rank of the named super- specific sections within this group is of little importance in com- parison to the error involved in the sequence given the species in the ' Check-List,' where the Canvasback is placed between the Redhead and the Scaups, and the Ring-necked Duck is put at the end of the series in the typical subgenus Marila. From a study of the literature of American Ducks it is evident that the belief prevails that the Ring-necked Duck (Marila col- laris) is a Scaup, very closely related to the Greater and Lesser Bluebills (Marila marila and M. -

New Zealand Birds and Vineyards of the South Island 16Th April to 24Th April 2023 (9 Days)

New Zealand Birds and Vineyards of the South Island 16th April to 24th April 2023 (9 days) Tui on Motuara Island, Marlborough Sound by Erik Forsyth RBL New Zealand – Birds & Wine Itinerary 2 New Zealand supports a host of unusual endemic land birds and a rich assemblage of marine birds and mammals. Starting in Christchurch, we head to Arthur’s Pass where we will be hiking through pristine Red Beech forest surrounded by breath-taking glacier-lined mountains, where Pipipi (Brown Creeper) Rifleman and the massive Kea can be found before we embark on another pelagic adventure into the fantastic upwelling off Kaikoura, searching for an abundance of albatrosses, shearwaters and petrels. Our last port of call is Picton where a chartered boat tour will take us through the Marlborough Sound to Motuara Bird Sanctuary, where the dazzling South Island Saddleback, Yellow-crowned Parakeet and New Zealand Robin will no doubt entertain us, With excellent lodging, vineyards, wines and meals, awe- inspiring scenery and fantastically friendly “Kiwis”, this is sure to be a tour of a lifetime! THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Christchurch Day 2 Christchurch to Arthur’s Pass Day 3 Arthur’s Pass area Day 4 Arthur’s Pass to Kaikoura Day 5 Kaikoura area Day 6 Kaikoura to Picton Day 7 Picton area Day 8 Picton to Christchurch Day 9 Departure RBL New Zealand – Birds & Wine Itinerary 3 TOUR ROUTE MAP… THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Christchurch. After breakfast we will visit Lake Ellesmere. This large lake supports a variety of ducks and geese and we will visit several sites to search for Australasian Shoveler, Grey Teal, Mallard, Canada Geese, Eurasian Coot and the endemic New Zealand Scaup. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

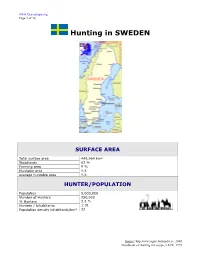

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Utilization of Hydrilla Verticillata by Wintering Waterfowl on the Tidal Potomac River

UTILIZATION OF HYDRILLA VERTICILLATA BY WINTERING WATERFOWL ON THE TIDAL POTOMAC RIVER by Jeffrey A. Browning Advisor: Dr. Albert Manville Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Johns Hopkins University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Johns Hopkins University May 2008 ABSTRACT Submersed aquatic vegetation (SAV) communities in the tidal Potomac River were decimated during the 20th century by multiple environmental and anthropogenic factors. With the major declines of SAV communities, waterfowl populations have declined greatly as well (Hindman 1989). Hydrilla verticillata, an introduced submersed aquatic plant, was first discovered in the tidal Potomac River in 1982 (Steward et al. 1984). One hundred nine waterfowl were collected from the tidal Potomac River and its tributaries during the 2007-2008 Virginian and Maryland waterfowl hunting seasons. The esophagi and gizzards were dissected and analyzed to determine the utilization of H. verticillata by wintering waterfowl. Only 2 duck species, Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) and Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis), consumed small amounts of H. verticillata, 2.52% and 0.20% aggregate percentage of esophageal content, respectively. An inverse relationship between H. verticillata and gastropod consumption was observed as the season progressed. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Albert Manville for his guidance and input during this research. Dr. Manville helped me reach decisions and get past certain obstacles. I would also like to thank Dr. Matthew Perry and Mr. Peter Osenton at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center for advice and consultation during the design of this study and analysis of the data. -

Temporal Changes in the Sex Ratio of the Common Pochard Aythya Ferina Compared to Four Other Duck Species at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK

140 Temporal changes in the sex ratio of the Common Pochard Aythya ferina compared to four other duck species at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK RUSSELL T. FREW1,*, KANE BRIDES1, TOM CLARE2, LAURI MACLEAN1, DOMINIC RIGBY3, CHRISTOPHER G. TOMLINSON2 & KEVIN A. WOOD1 1Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK. 2Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Martin Mere, Fish Lane, Burscough, Lancashire L40 0TA, UK. 3Conservation Contracts Northwest Ltd. Horwich, Bolton, Lancashire BL6 7AX, UK. *Correspondence author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Duck populations tend to have male-biased adult sex ratios (ASRs). Changes in ASR reflect species demographic rates; increasingly male-biased populations are at risk of decline when the bias results from falling female survival. European and North African Common Pochard Aythya ferina numbers have declined since the 1990s and show increasing male bias, based on samples from two discrete points in time. However, lack of sex ratio (SR) data for common duck species inhibits assessing the pattern of change in the intervening period. Here, we describe changes in annual SR during winters 1991/92–2005/06 for five duck species (Common Pochard, Gadwall Mareca strepera, Northern Pintail Anas acuta, Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata and Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula) at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK. Pochard, Pintail, Tufted Duck and Shoveler showed significantly male-biased SRs, with the male bias increasing in Pochard and Shoveler, exhibiting a weak decrease in Pintail, and with no significant trend recorded for Tufted Duck or Gadwall. The increasing male-biased Pochard SR at Martin Mere contrasts with the stable trend for Britain, suggesting that site trends may not reflect those at the national level. -

Red-Breasted Goose

Urgent preliminary assessment of ornithological data relevant to spread of Avian Influenza in Europe Ward Hagemeijer Wetlands International Commissioned by DG Environment to Wetlands International and Euring Data needs for risk assessment: ornithology (virology) Quantified risk assessment: Research and Monitoring programme A. Birds as a vector 1.Quantified bird migration information: satellite telemetry, ringing data analysis, count data analysis 2.Quantified frequency of occurrence of virus in wild birds: surveillance 3.Ecology of virus in wild birds: virological research on wild birds B. Impact on wild bird populations Different components of the project Activities to be undertaken: • identification of Higher Risk Species (HRS) • analysis of their migration routes (ringing and count data) • identification of concentration and mixing sites • rapid assessment planning for wetland sites Analysis of higher risk species Identification of HRS on basis of: • occurence of LPAI viruses • ecology and behaviour • contact risk with poultry • numbers within EU In collaboration with David Stroud and Rowena Langston Occurrence of LPAI in wild birds species Results 1999 – 2004 Erasmus University Netherlands Species N Tested N PCR+ (%) N Egg + Mallard 6822 489 (7.2) 267 Eurasian Wigeon 1470 22 (1.5) 4 Common Teal 670 18 (2.7) 4 Northern Pintail 135 4 (3.0) 1 Northern Shoveler 90 1 (1.1) 1 Shelduck, Eider, Gadwall, Tufted, Garganey 238 0 (0.0) 0 Greater White-fronted Goose 1696 19 (1.1) 5 Greylag Goose 303 8 (2.6) 4 Brent, Barnacle, Bean, Egyptian, Canada, Pink-f 1202 0 (0.0) 0 Black-headed Gull 993 10 (1.0) 6 Common, Herring, Black-backed, Kittiwake 1976 0 (0.0) 0 Guillemot 698 3 (0.4) 1 Other birds 10909 0 0 + + + 27204 574 (2.1) 295 Selection of taxonomic groups • Anseriformes and Charadriiformes, • Migratory • Occurring in Europe.