Cambodia 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Oman HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

Technical Notes

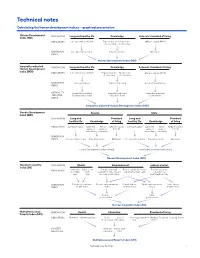

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

The Human Development Index

32 ADOPTION The Human Development Index – a better indicator for success? When faced with the complexity of the Sustainable Development Goals, we need a digestible, precise way of measuring progress By Hayley Lashmar, to a country’s wealth, or even GDP per framework swells in complexity – with 17 United Nations Association – UK capita, which tells us something about an goals, 169 targets and even more indicators individual’s means but nothing about their – there is also a need for a simple way to roduced by the UN Development life outcomes. measure progress. Over a 15-year timeframe, Programme in 1990, the firstHuman Of course, the HDI has its limitations. the HDI will do a better job than GDP of PDevelopment Report outlined a new It omits several factors that can have a capturing what progress is being achieved. approach to development, focused on people significant influence on quality of life, such It reflects a more nuanced understanding and their opportunities rather than economic as environmental degradation. Industrial of human development while being simple growth alone. The Human Development pollution and deforestation, for example, enough to remain inclusive: unlike other Index (HDI) was introduced as a way to can lead to complex health problems more complex indices, the HDI is based on quantify this approach. Nearly 30 years (e.g. lymphatic filariasis) or mental health data that is likely to have been collected in later, the Sustainable Development Goals conditions that do not necessarily have an many countries for a number of years. have rekindled discussions on how we impact on mortality rates but which can Despite this, most countries still use measure progress. -

Human Development Report 2016

Human Development Report 2016 Human Development for Everyone Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Human Development Report 2016 | Human Development for Everyone for Development Human | Report 2016 Development Human The 2016 Human Development Report is the latest in the series of global Human Development Reports published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) since 1990 as independent, analytically and empirically grounded discussions of major development issues, trends and policies. Additional resources related to the 2016 Human Development Report can be found online at http://hdr.undp.org, including digital versions of the Report and translations of the overview in more than 20 languages, an interactive web version of the Report, a set of background papers and think pieces commissioned for the Report, interactive maps and databases of human development indicators, full explanations of the sources and methodologies used in the Report’s composite indices, country profiles and other background materials as well as previous global, regional and national Human Development Reports. The 2016 Report and the best of Human Development Report Office content, including publications, data, HDI rankings and related information can also be accessed on Apple iOS and Human Development AndroidReport smartphones2016 via a new and easy to use mobile app. Human Development for Everyone The cover reflects the basic message that human development is for everyone—in the human development journey no one can be left out. Using an abstract approach, the cover conveys three fundamental points. First, the upward moving waves in blue and whites represent the road ahead that humanity has to cover to ensure universal human development. -

A Proposal for a Modified Human Development Index

A proposal for a modified Human Development Index María Andreina Salas-Bourgoin ABSTRACT The Human Development Index (HDI) is an indicator designed to track the development of countries in respect of three dimensions of development: health, education and income. Since it was first published in 1990, great efforts have been made to improveHDI , which, as has been stressed on numerous occasions, cannot be seen as a definitive measure of development. This paper includes a reflection on what constitutes human development, the pillars underpinning it and two new dimensions that should be incorporated into HDI (employment and political freedoms) for it to better express progress in development. This document will also present, in addition to the modifiedHDI , detailed instructions for its calculation and an annex including modified HDI scores for 117 countries. KEYWORDS Human development, measurement, undp, economic indicators, social indicators, statistical methodology, statistical data JEL CLASSIFICATION I31, I32, I39 AUTHOR María Andreina Salas-Bourgoin is a full-time assistant professor at the Institute of Geography and Natural Resource Conservation of the University of Los Andes, Merida, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. [email protected] 30 CEPAL REVIEW 112 • APRIL 2014 I Introduction The Human Development Index (hdi) is an aggregated Therefore, with a view to fuelling further debate on these indicator, designed by the United Nations Development issues, a proposal has been made for a modified hdi, Programme (undp) to track progress in the -

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2016 Human Development for Everyone

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2016 Human Development for Everyone Statistical annex Readers guide 193 Statistical tables Human development composite indices 1 Human Development Index and its components 198 2 Human Development Index trends, 1990–2015 202 3 Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index 206 4 Gender Development Index 210 5 Gender Inequality Index 214 6 Multidimensional Poverty Index: developing countries 218 Human development indicators 7 Population trends 222 8 Health outcomes 226 9 Education achievements 230 10 National income and composition of resources 234 11 Work and employment 238 12 Human security 242 13 International integration 246 14 Supplementary indicators: perceptions of well-being 250 15 Status of fundamental human rights treaties 254 Human development dashboards 1 Life-course gender gap 259 2 Sustainable development 264 Regions 269 Statistical references 270 Statistical annex | 191 Readers guide The 17 statistical tables in this annex provide an overview of Comparisons over time and across editions key aspects of human development. The first six tables contain of the Report the family of composite human development indices and their components estimated by the Human Development Report Because national and international agencies continually Office (HDRO). The remaining tables present a broader set of improve their data series, the data — including the HDI values indicators related to human development. The two dashboards and ranks — presented in this Report are not comparable to introduce partial groupings of countries according to their those published in earlier editions. For HDI comparability performance on each indicator. across years and countries see table 2, which presents trends Unless otherwise noted, tables use data available to the using consistent data. -

Human Security GN

United Nations Development Programme Human Development Report e National Human Development Report Series NHDR Occasional Paper 3 Conict Prevention Thematic Guidance Note 3 By Marc-André Franche with Michi Ebata United Nations Development Programme National Human Development Report Unit/HDRO Bureau for Conflict Prevention and Recovery Conflict Prevention NHDR Thematic Guidance Note* August 2004 * By Marc-André Franche with contributions from Pablo Ruiz, Ana Cutter, Arkadi Toritsyn, Sarah Burd-Sharps Devanand Ramiah, Dirk Boberg, Michi Ebata, Céline Moyroud, Francesca Cook, Misaki Watanabe, Moncef Ghrib, Natasha Loayza and Sharmila Kurukulasuriya and Noha Aboueldahab Table of Contents: Introduction: Part 1: Conceptual note A. Conflict and Conflict Prevention What do we mean by conflict and conflict prevention? Conflict Analysis The need to integrate conflict prevention in development B. Human Security: C. Key elements of a conceptual fra mework for NHDRs on conflict a nd conflict prevention 1. The impact of violent conflict on human development (VC → HD) 2. The enlargement of people’s choices as a conflict prevention and violence reduction strategy (HD → VC) Part 2: Guidance note for NHDRs on conflict and conflict prevention A. Selecting conflict and conflict prevention as a theme B. The importance of an inclusive and participatory process C. Essential steps to elaborate an NHDR on conflict prevention 1. Identify and analyze the conflict according to its “human” weight 2. Establish the impact of violent conflict on human security and human development i. Human security: ii. Other components of human development: iii. Human Development Index: iv. Vulnerable groups: 3. Prioritize and analyze threats and causes of conflict according to their “human” weight 4. -

The Capabilities Approach, Millennium Development Goals, and Human Development Index

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies Josef Korbel School of International Studies Summer 2012 An Assessment of Human Development in Uganda: The Capabilities Approach, Millennium Development Goals, and Human Development Index Jordan Farrar University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/advancedintlstudies Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jordan Farrar, “An Assessment of Human Development in Uganda: The Capabilities Approach, Millennium Development Goals, and Human Development Index,” Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies 4 (Summer 2012): 74-101 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. An Assessment of Human Development in Uganda: The Capabilities Approach, Millennium Development Goals, and Human Development Index This article is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/advancedintlstudies/8 An Assessment of Human Development in Uganda THE CAPABILITIES APPROACH, MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS, AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX JORDAN FARRAR University of Denver Ph.D. Candidate, Social Work The Millennium Development Goals, grounded in Martha Nussbaum and Amaryta Sen’s Capabilities Approach and manifested through the Human Development Index, represent the contemporary means aimed at improving the overall quality of life for the people of the world. Currently Uganda is making substantial progress to achieve poverty reduction, increase overall health and ensure universal primary education. -

Human Development Report Woman to Lead the Organisation

Chapter 2 Helen Clark became the The real wealth of nations: Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Lessons from the in April 2009, and is the first Human Development Report woman to lead the organisation. She is also the Chair of the Helen Clark United Nations Development Group, a committee consisting of the heads of all United Nations funds, programmes and departments working on development issues. th Prior to her appointment Helen Clark takes the opportunity of the 50 with UNDP, Ms Clark served as anniversary of the OECD Development Assistance Prime Minister of New Zealand, Committee (DAC) to explore the human development serving three successive terms progress over the past decade, as well as challenges (1999-2008). She engaged widely in of the 21st century. She bases her analysis on a rich policy development and advocacy source of insights, the annual Human Development across the international, economic, social and cultural spheres. Report, produced by the United Nations Development Under her leadership, New Zealand Programme (UNDP) on issues as diverse as gender, achieved significant economic growth, water, human rights, climate change and migration. low levels of unemployment and high She notes that people today are, on average, healthier, levels of investment in education and more educated and wealthier than ever before. health, and in the well-being While the income divide has generally worsened, gaps of families and older citizens. Ms Clark advocated strongly for in health and education outcomes between developed New Zealand’s comprehensive and developing countries have narrowed. programme on sustainability Looking ahead, it remains vital that all partners in and tackling the problems of climate change. -

Gender Development Index

TABLE 4 Gender Development Index SDG 3 SDG 4.3 SDG 4.4 SDG 8.5 Estimated gross national Gender Development Index Human Development Index Life expectancy at birth Expected years of schooling Mean years of schooling income per capitaa Value (years) (years) (years) (2017 PPP $) Value Groupb Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male HDI RANK 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019 2019c 2019c 2019c 2019c 2019 2019 Very high human development 1 Norway 0.990 1 0.949 0.959 84.4 80.4 18.8 d 17.4 13.0 12.8 58,548 74,280 2 Ireland 0.981 1 0.943 0.961 83.9 80.7 18.8 d 18.6 d 12.9 12.4 55,540 81,401 e 2 Switzerland 0.968 2 0.934 0.965 85.6 81.9 16.2 16.4 12.7 13.6 57,840 81,137 e 4 Hong Kong, China (SAR) 0.972 2 0.933 0.959 87.7 82.0 17.1 16.8 11.9 12.7 45,961 82,993 e 4 Iceland 0.969 2 0.933 0.963 84.5 81.5 20.2 d 18.0 d 12.6 f 13.0 f 46,413 62,883 6 Germany 0.972 2 0.933 0.960 83.7 78.9 16.9 17.0 13.9 14.4 45,277 65,599 7 Sweden 0.983 1 0.936 0.953 84.6 81.0 20.4 d 18.6 d 12.7 12.4 47,709 61,287 8 Australia 0.976 1 0.932 0.955 85.4 81.5 22.4 d 21.5 d 12.8 f 12.7 f 39,287 56,954 8 Netherlands 0.966 2 0.926 0.960 84.0 80.6 18.8 d 18.2 d 12.2 12.7 46,815 68,685 10 Denmark 0.983 1 0.931 0.948 82.9 78.9 19.6 d 18.3 d 12.8 f 12.4 f 49,296 68,134 11 Finland 0.990 1 0.932 0.942 84.7 79.1 20.2 d 18.6 d 13.0 12.6 40,759 56,485 11 Singapore 0.985 1 0.931 0.945 85.7 81.5 16.7 16.3 11.2 12.1 71,387 103,421 e 13 United Kingdom 0.970 2 0.916 0.944 83.0 79.6 18.0 17.0 13.2 13.2 33,323 59,135 14 Belgium 0.974 2 0.918 0.943 83.9 79.3 20.7 d 18.8 d 11.9 g 12.2 g 41,948 62,427 14 New Zealand 0.964 2 0.912 0.946 84.0 80.6 19.7 d 17.9 12.7 f 12.9 f 31,233 50,693 16 Canada 0.986 1 0.922 0.935 84.4 80.4 16.7 15.7 13.4 f 13.3 f 39,459 57,734 17 United States 0.994 1 0.922 0.928 81.4 76.3 16.9 15.7 13.5 13.4 50,590 77,338 e 18 Austria 0.964 2 0.903 0.937 83.9 79.2 16.4 15.8 12.2 f 12.9 f 39,386 73,528 19 Israel 0.973 2 0.904 0.929 84.5 81.3 16.8 15.6 13.1 13.0 29,665 50,819 19 Japan 0.978 1 0.906 0.927 87.7 81.5 15.2 15.3 13.1 h 12.6 h 30,584 55,869 19 Liechtenstein . -

Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 – Statistical Update

Human Development Indices and Indicators | 2018 Statistical Update Statistical 2018 | Indicators and Indices Development Human Summary Human Development Indices and Indicators 2018 Statistical Update The cover reflects human development progress over 1990–2017 in terms of Human Development Index (HDI) values and the number of people in the four human development categories. In the figure each slice’s innermost band represents the population in that human development category, and the height of the slice reflects its HDI value. The cover reflects that even though the global population increased from 5 billion to 7.5 billion between 1990 and 2017, the number of people in low human development fell from 3 billion to 926 million—or from 60 percent of the global population to 12 percent—and that the number of people in high and very high human development more than tripled, from 1.2 billion to 3.8 billion—or from 24 percent of the global population to 51 percent. ent elopm Ve dev ry h an igh m hu hu Hum m w an D an o ev d L elo e pm ve 0.8 en lo 94 t I p nd m 0.504 e e x n v a t lu e 6 m 1.439 b 92 n pe o p l e M 2017 2 e . 7 d 3 i n u 3 HDI b m b n 9 7 h 0.645 .3 u 2 m a n d e t v n e e lo m p p m lo e 0.757 e n v t e d an um h gh Hi Copyright @ 2018 By the United Nations Development Programme 1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017 USA All rights reserved.