Lucan's Bellum Ciuile and the Epic Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Antaeus the Conqueror Antaeus Is an Ancient Greek Mythological Person

Page 1 of 7 Yarra Valley Anglican Church – Sunday 24th May, 2020 Romans 8:31-39 God is for us, Therefore… All Things Work For Our Good Rev Matthew Smith 1. Antaeus the Conqueror Antaeus is an Ancient Greek Mythological person. He was the giant son of Poseidon, god of the Sea, And Gaia, god of the Earth. Antaeus was a legendary wrestler. He challenged everyone who passed by his area to a wrestling match. And he never lost; he was invincible, Antaeus conquered all. But there’s a secret to why he always won his wrestling matches. Antaeus drew strength from his mother, the earth. As long as he was in contact with the earth, he drew power. So think about: In Greek wrestling, like the Olympic sport, The goal is to force your opponents to the ground, Pinning them to the earth. But when Antaeus is pinned to the earth, His strength returns and grows, Enabling him to overcome his opponent. Now let’s be clear: This is myth. Fiction. Not historical truth. Greek Myth is very different to the Christian Gospel. Jesus Christ is not myth, not fiction. His life, his death, his resurrection, his ascension. It’s all a matter of historical record. We believe the Gospel because it’s all true. But while the story of Antaeus is a myth, It offers us an interesting illustration. Antaeus was the all-conquering wrestler. And Paul tells Christians in Romans 8: We are more than conquerors. 2. God is For Us Today we conclude our series on Romans ch.8. -

The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen

Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Howard Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen This dissertation analyzes the three main protagonists of Lucan’s Bellum Civile through their attempts to utilize, resist, or match a pattern of action which I call the “formula.” Most evident in Caesar, the formula is a cycle of alternating states of energy that allows him to gain a decisive edge over his opponents by granting him the ability of perpetual regeneration. However, a similar dynamic is also found in rivers, which thus prove to be formidable adversaries of Caesar in their own right. Although neither Pompey nor Cato is able to draw on the Caesarian formula successfully, Lucan eventually associates them with the river-derived variant, thus granting them a measure of resistance (if only in the non-physical realm). By tracing the development of the formula throughout the epic, the dissertation provides a deeper understanding of the importance of natural forces in Lucan’s poem as well as the presence of an underlying drive that unites its fractured world. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................ vi Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium*

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium* MELINDA SZEKELY Pliny the Elder writes the following about the king of Taprobane1 in the sixth book of his Natural History: "eligi regem a populo senecta clementiaque, liberos non ha- bentem, et, si postea gignat, abdicari, ne fiat hereditarium regnum."2 This account es- caped the attention of the majority of scholars who studied Pliny in spite of the fact that this sentence raises three interesting and debated questions: the election of the king, deposal of the king and the heredity of the monarchy. The issue con- cerning the account of Taprobane is that Pliny here - unlike other reports on the East - does not only use the works of former Greek and Roman authors, but he also makes a note of the account of the envoys from Ceylon arriving in Rome in the first century A. D. in his work.3 We cannot exclude the possibility that Pliny himself met the envoys though this assumption is not verifiable.4 First let us consider whether the form of rule described by Pliny really existed in Taprobane. We have several sources dealing with India indicating that the idea of that old and gentle king depicted in Pliny's sentence seems to be just the oppo- * The study was supported by OTKA grant No. T13034550. 1 Ancient name of Sri Lanka (until 1972, Ceylon). 2 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 89. Pliny, Natural History, Cambridge-London 1989, [19421], with an English translation by H. Rackham. 3 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 85-91. Concerning the Singhalese envoys cf. -

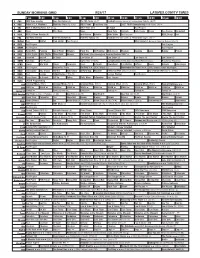

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

PRIMITIVE POLITICS: LUCAN and PETRONIUS Martha Malamud in Roman Literature, Politics and Morality Are Not Distinct Categories

CHAPTER TWELVE PRIMITIVE POLITICS: LUCAN AND PETRONIUS Martha Malamud In Roman literature, politics and morality are not distinct categories: both are implicated in the construction and maintenance of structures of power. Roman virtues are the basis of the res publica, the body politic. In what follows, I take “politics” in a broad sense: “public or social ethics, that branch of moral philosophy dealing with the state or social organism as a whole.”1 As Edwards puts it, “issues which for many in the pres- ent day might be ‘political’ or ‘economic’ were moral ones for Roman writers, in that they linked them to the failure of individuals to control themselves.”2 What follows is a case study of how Lucan and Petronius deploy a pair of motifs popular in Roman moralizing discourse (primi- tive hospitality, as exemplifi ed by the simple meal, and primitive archi- tecture) in ways that refl ect on the politics of early imperial Rome. Embedded in the moralizing tradition is the notion of decline. Roman virtue is always situated in the past, and visions of the primitive, such as the rustic meal and the primitive hut, evoke comparisons with a corrupted present. These themes are present in Roman literature from an early period. Already by the third century bce, there is a growing preoccupation with a decline in ethical standards attributed to luxury and tied to the expansion of Roman power and changes in Rome’s political structure. Anxiety focused around luxurious foods, clothing, art, and architecture. As Purcell observes of Roman views of their own food history, “[d]iet-history is a subdivision of that much larger way of conceptualizing passing time, the history of moral decline and recovery; indeed, it is a way of indexing that history,”3 and one can say the same of architecture-history. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Getting to Know Martial

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82822-2 - Martial’s Rome: Empire and the Ideology of Epigram Victoria Rimell Excerpt More information introduction Getting to know Martial tu causa es, lector amice, mihi, qui legis et tota cantas mea carmina Roma. Ep. ..– Think back. It’s the mid-nineties. We are on the brink of a new century, and are living and breathing the ‘New Age’ people have been preaching about since the eighties. Thanks to more efficient communication, and the regularising machine of empire, the world seems to have got smaller, and more and more provincials are gravitating towards the sprawling, crowded metropolis, all manically networking to win the same few jobs (they all want to be ‘socialites’, or ‘artists’). Many of us are richer and more mobile than ever, but arguably have less freedom. Modern life is a struggle, it seems – it’s dog eat dog in the urban jungle, and those who can’t keep up the pace soon become victims (actually, being a ‘victim’ is the in thing). ‘Reality’ is the hottest show in town: we’re done with drama and fantasy, as amateur theatrics and seeing people actually suffer is such a blast (as well as being a really ‘ironic’ creative experiment). This is a culture that has long realised Warhol’s prophecy, where everyone wants their bite of the fame cherry, but where fame itself is a dirty shadow of what it used to be. The young recall nothing but peace, yet fierce wars still bristle at the world’s edges, and even as the concrete keeps rising, a smog of instability and malaise lingers. -

LUCAN's CHARACTERIZATION of CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH By

LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY (Under the Direction of Thomas Biggs) ABSTRACT This thesis examines Caesar’s three extended battle exhortations in Lucan’s Bellum Civile (1.299-351, 5.319-364, 7.250-329) and the speeches that accompany them in an effort to discover patterns in the character’s speech. Lucan did not seem to develop a specific Caesarian style of speech, but he does make an effort to show the changing relationship between the General and his soldiers in the three scenes analyzed. The troops, initially under the spell of madness that pervades the poem, rebel. Caesar, through speech, is able to bring them into line. Caesar caters to the soldiers’ interests and egos and crafts his speeches in order to keep his army working together. INDEX WORDS: Lucan, Caesar, Bellum Civile, Pharsalia, Cohortatio, Battle Exhortation, Latin Literature LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY B.A., The College of Wooster, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth Talbot Neely All Rights Reserved LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY Major Professor: Thomas Biggs Committee: Christine Albright John Nicholson Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

May 16, 2012 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 16, 2012 • VOL. 23, NO. 2 $1.25 Congratulations to Ice Pool Winner KLONDIKE Mandy Johnson. SUN Breakup Comes Early this Year Joyce Caley and Glenda Bolt hold up the Ice Pool Clock for everyone to see. See story on page 3. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue SOVA Graduation 18 Andy Plays the Blues 21 The Happy Wanderer 22 Summer 2012 Year Five had a very close group of The autoharp is just one of Andy Paul Marcotte takes a tumble. students. Cohen's many instruments. Store Hours See & Do in Dawson 2 AYC Coverage 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 DCMF Profile 19 Kids' Corner 26 Uffish Thoughts 4 TV Guide 12-16 Just Al's Opinion 20 Classifieds 27 Problems at Parks 5 RSS Student Awards 17 Highland Games Profiles 24 City of Dawson 28 P2 WEDNESDAY, May 16, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to close. More live entertainment in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 SEE AND DO p.m.The toDowntown 8:30 p.m. Hotel LIVE MUSIC: - in DAWSON now: Barnacle Bob is now playing in the Sourdough Saloon ev eryThe Thursday, Eldorado Friday Hotel and Saturday from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may Food Service Hours: 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., seven days a week. Check out need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To our Daily Lunch Specials. -

Pliny's "Vesuvius" Narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20)

Edinburgh Research Explorer Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20) Citation for published version: Berry, D 2008, Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20). in F Cairns (ed.), Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar . vol. 13, Francis Cairns Publications Ltd, pp. 297-313. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Published In: Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar Publisher Rights Statement: ©Berry, D. (2008). Letters from an advocate: Pliny's "Vesuvius" narratives (Epistles 6.16, 6.20). In F. Cairns (Ed.), Papers of the Langford Latin Seminar . (pp. 297-313). Francis Cairns Publications Ltd. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 LETTERS FROM AN ADVOCATE: Pliny’s ‘Vesuvius’ Narratives (Epp. 6.16, 6.20)* D.H. BERRY University of Edinburgh To us in the modern era, the most memorable letters of Pliny the Younger are Epp. 6.16 and 6.20, addressed to Cornelius Tacitus. -

C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts Of

Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. Evans http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=17141, The University of Michigan Press C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts of Ancient Rome o the distinguished Giovanni Lucio of Trau, Raffaello Fabretti, son of T Gaspare, of Urbino, sends greetings. 1. introduction Thanks to your interest in my behalf, the things I wrote to you earlier about the aqueducts I observed around the Anio River do not at all dis- please me. You have in›uenced my diligence by your expressions of praise, both in your own name and in the names of your most learned friends (whom you also have in very large number). As a result, I feel that I am much more eager to pursue the investigation set forth on this subject; I would already have completed it had the abundance of waters from heaven not shown itself opposed to my own watery task. But you should not think that I have been completely idle: indeed, although I was not able to approach for a second time the sources of the Marcia and Claudia, at some distance from me, and not able therefore to follow up my ideas by surer rea- soning, not uselessly, perhaps, will I show you that I have been engaged in the more immediate neighborhood of that aqueduct introduced by Pope Sixtus and called the Acqua Felice from his own name before his ponti‹- 19 Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013).