Uni> Licroriims Intemdtkxvil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Officiel N°2020-59

N° 59 Dimanche 16 Safar 1442 59ème ANNEE Correspondant au 4 octobre 2020 JJOOUURRNNAALL OOFFFFIICCIIEELL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX - LOIS ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE) Algérie ETRANGER DIRECTION ET REDACTION Tunisie SECRETARIAT GENERAL ABONNEMENT Maroc (Pays autres DU GOUVERNEMENT ANNUEL Libye que le Maghreb) WWW.JORADP.DZ Mauritanie Abonnement et publicité: 1 An 1 An IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE Les Vergers, Bir-Mourad Raïs, BP 376 ALGER-GARE Edition originale................................... 1090,00 D.A 2675,00 D.A Tél : 021.54.35..06 à 09 Fax : 021.54.35.12 Edition originale et sa traduction.... 2180,00 D.A 5350,00 D.A C.C.P. 3200-50 Clé 68 ALGER (Frais d'expédition en sus) BADR : Rib 00 300 060000201930048 ETRANGER : (Compte devises) BADR : 003 00 060000014720242 Edition originale, le numéro : 14,00 dinars. Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 28,00 dinars. Numéros des années antérieures : suivant barème. Les tables sont fournies gratuitement aux abonnés. Prière de joindre la dernière bande pour renouvellement, réclamation, et changement d'adresse. Tarif des insertions : 60,00 dinars la ligne 16 Safar 1442 2 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE N° 59 4 octobre 2020 SOMMAIRE DECRETS Décret exécutif n° 20-274 du 11 Safar 1442 correspondant au 29 septembre 2020 modifiant et complétant le décret exécutif n° 96-459 du 7 Chaâbane 1417 correspondant au 18 décembre 1996 fixant les règles applicables aux -

Multivariate Analysis to Assess the Quality of Irrigation Water in a Semi-Arid Region of North West of Algeria : Case of Ghrib Dam

Multivariate Analysis to Assess the Quality of Irrigation Water in a Semi-Arid Region of North West of Algeria : Case of Ghrib Dam FAIZA HALLOUZ ( [email protected] ) Universite de Khemis Miliana, LGEE, ENSH, BLIDA https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6644-5756 Mohamed Meddi Ecole Nationale Superieure de l'Hydraulique Salaheddine Ali Rahmani University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene: Universite des Sciences et de la Technologie Houari Boumediene Research Article Keywords: Ghrib dam, IWQI, SAR, physical and chemical parameters, pollution, water, irrigation. Posted Date: June 15th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-206444/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/20 Abstract Dams are critical to agriculture, industry, and the needs of humans and wildlife. This study evaluates the water quality of the Ghrib dam in north west of Algeria, using Irrigation Water Quality Index (IWQI), sodium absorption rates (SAR) and multivariate statistical methods (Clustering and principal component − analysis). The study concerns the analysis of physical and chemical parameters (pH, EC, O2, TUR, Ca, Mg, HCO3, Na, K, BOD, DCO, Cl , PO4, SO3. NH4 et NO3) which were measured at twelve selected points along the dam over 8 periods (dry and wet periods) using standard methods. Irrigation Water Quality Index values in the dam were found to be between 41 and 59, according to classications for different water uses, values below 60 indicate that water is of poor quality for irrigation and treatment is recommended to make dam water more suitable for irrigation. -

Liste Des Medecins Specialists

LISTE DES MEDECINS SPECIALISTS N° NOM PRENOM SPECIALITE ADRESSE ACTUELLE COMMUNE 1 MATOUK MOHAMED MEDECINE INTERNE 130 LOGTS LSP BT14 PORTE 122 BAGHLIA 2 DAFAL NADIA OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE EL LOUZ VILLA N° 24 BENI AMRANE 3 HATEM AMEL GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE CHAALAL MED LOT 02 1ERE ETAGE BENI AMRANE 4 BERKANE FOUAD PEDIATRIE RUE BOUIRI BOUALELM BT 01 N°02 BOR DJ MENAIEL 5 AL SABEGH MOHAMED NIDAL UROLOGIE RUE KHETAB AMAR , BT 03 , 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 6 ALLAB OMAR OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE 250 LOGTS, BT N ,CAGE 01 , N° 237 BORDJ MENAIEL 7 AMNACHE OMAR PSYCHIATRIE CITE 96 LOGTS , BT 03 BORDJ MENAIEL 8 BENMOUSSA HOCINE OPHTALMOLOGIE CITE MADAOUI ALI , BT 08, 1ER ETAGE BORDJ MENAIEL 9 BERRAZOUANE YOUCEF RADIOLOGIE CITE ELHORIA ,LOGTS N°03 BORDJ MENAIEL 10 BOUCHEKIR BADIA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE CITE DES 250 LOGTS, N° 04 BORDJ MENAIEL 11 BOUDJELLAL MOHAMMED OUALI GASTRO ENTEROLOGIE CITE DES 92 LOGTS, BT 03, N° 01 BORDJ MENAIEL 12 BOUDJELLAL HAMID OPHTALMOLOGIE BORDJ MENAIEL BORDJ MENAIEL 13 BOUHAMADOUCHE HAMIDA GYNECOLOGIE OBSTETRIQUE RUE AKROUM ABDELKADER BORDJ MENAIEL 14 CHIBANI EPS BOUDJELLI CHAFIKA MEDECINE INTERNE ZONE URBAINE II LOT 55 BORDJ MENAIEL 15 DERRRIDJ HENNI RADIOLOGIE COPPERATIVE IMMOBILIERE EL MAGHREB ALARABI BORDJ MENAIEL 16 DJEMATENE AISSA PNEUMO- PHTISIOLOGIE CITE 24 LOGTS BTB8 N°12 BORDJ MENAIEL 17 GOURARI NOURREDDINE MEDECINE INTERNE RUE MADAOUI ALI ECOLE BACHIR EL IBRAHIMI BT 02 BORDJ MENAIEL 18 HANNACHI YOUCEF ORL CITE DES 250 LOGTS BT 31 BORDJ MENAIEL 19 HUSSAIN ASMA MEDECINE INTERNE 78 RUE KHETTAB AMAR BORDJ MENAIEL 20 -

Liste Chirurgiens-Dentistes – Wilaya De Boumerdes

LISTE CHIRURGIENS-DENTISTES – WILAYA DE BOUMERDES N° NOM PRENOM ADRESSE ACTUELLE COMMUNE DAIRA 1 AMARA DAHBIA CITE NOUVELLE N°27 HAMADI KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 2 AISSAOUI HASSIBA RUE ZIANE LOUNES N°04 2EME ETAGE BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 3 ASSAS SADEK HAI ALLILIGUIA N° 34 BIS BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 4 ABIB KAHINA MANEL CITE DES 850 LOGTS BT 16 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 5 ABBOU EPS GOURARI FERIEL HAI EL MOKHFI LOT N° 02 PORTE N° 01 OULED HADADJ BOUDOUAOU 6 ADJRID ASMA HAI 20 AOUT LOT N°181 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 7 ADJRID HANA COP- IMMOB EL AZHAR BT 22 1ER ETAGE A DROITE BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 9 AZZOUZ HOURIA CITE 11 DECEMBRE 1960 BT 06 N°04 BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 10 AZZEDDINE HOURIA LOTISSEMENT II VILLA N°213 BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 11 ALLOUCHE MOULOUD RUE ABANE RAMDANE DELLYS DELLYS 12 AOUANE NEE MOHAD SALIHA OULED HADADJ OULED HADADJ BOUDOUAOU 13 ALLOUNE DJAMEL CITE 850 LOGTS BT 37 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU 14 ACHLAF AHCENE 4, RUE ALI KHOUDJA N°1A TIDJELABINE BOUMERDES 15 ARAB AMINA CITE DES 200 LOGTS BT B1 CAGE B N°03 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 16 AIT AMEUR EPSE ARIB NACERA CITE DES 850 LOGTS BT 16 N°02 BOUDOUAOU BOUDOUAOU KARIMA AICHAOUI HASSIBA RUE ZIANE LOUNES N°04 2EME ETAGE BORDJ-MENAIEL BORDJ-MENAIEL 17 ARGOUB KENZA CITE DES 82 LOGTS BT A N°05 ISSER ISSER 18 ALOUACHE NORA CITE 919 LOGTS BT 20 N°10S TIDJELABINE BOUMERDES 19 BERRABAH HICHAM CITE 20 AOUT BT J N°92 BOUMERDES BOUMERDES 20 BRADAI KHALIDA 20 RUE FAHAM DJILLALI KHEMIS EL KHECHNA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA 21 BENINAL LYNDA CITE 200 LOGTS 70 BIS N°02 OULED MOUSSA KHEMIS EL KHECHNA -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 7419-AL Algeria Agriculture:A New Opportunityfor Growth Public Disclosure Authorized April5, 1990 AgricultureOperations Division CountryDepartment II Europe,Middle Eastand North Africa RegionalOffice FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the WorldBank This documenthas a restricteddistribution and may be usedby recipients only in the performanceof their official dut;es.Its contents may not otherwise be disclosedwithout World Bankauthorization. CURRENCY AND EQUIVALENT UNITS Currency Unit Algerian Dinar (DA) US$1.00 DA 7.5 (1989 average) DA 1.00 US$0.13 (1989 average) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS APF - Accession A la Propri6t6 Fonciere BADR - Banque de l'Agricultureet du D6veloppementRural CCLS - Cooperativesdes Cer6ales et des Legumes Secs DAS - bomaines Agricoles Socialistes EAC/EAI - ExploitationsAgricoles Collectives/ ExploitationsAgricoles Individuelles EEC - European Economic Community INRAA - InstitutNational de la Recherche Agronomiqued'Alg6rie LSI - Large Scale Irrigation ME - Minist6re de 1'Equipement OER - Official Exchange Rate OAIC - Office Alg6rien Inter-professionneldes C6r6ales O&M - Operation and Maintenance OPI - Offices des P6rimetresd'Irrigation. SER - Shadow Exchange Rate SSI - Small Scale Irrigation UNDP - United Nations DevelopmentProgram FOR OFfICLALUSE ONLY ALGERIA AGRICULTURE:A NEW OPPORTUNXTY FOR GROWTH Table of Contents Page Number EXECUTIVE-SUMMARY ..... i PART I. ALGERIAN AGRICULTURE: THE PAST IN PERSPECTIVEAND POTENTIAL FOR GK3WTH I. BACKGROUND ..... 1 A. General Economic Framework . 1 B. AgriculturalOverview . 2 II. PAST AGRICUTURAL PERFORMANCE . 8 A. Introduction ..... 8 B. Level of Food Self-Sufficiency . 9 C. Yields ............. ..... 10 D. The Dual Nature of the Agricultural Sector . .11 III. SOURCES OF PAST GROWTH.14 A. Overview . .14 B. Changes in Area Cultivated . -

The Sand Filterers

1 The sand filterers Majnoun, the passionate lover of Leila, wandering in the desert, was seen one day filtering sand in his hands. “What are you looking for?” He was asked. “I am looking for Leila.” “How can you expect to find such a pure pearl like Leila in this dust?” “I look for Leila everywhere”, replied Majnoun, “hoping to find her one day, somewhere.” Farid Eddin Attar, as reported by Emile Dermenghem, Spiritual Masters’ Collection. 2 Introduction Whatever judgment passed in the future on Mostefa Ben Boulaid, Bachir Chihani or Adjel Adjoul, a place in the mythical Algerian revolution will be devoted to them. Many controversies will arise concerning the nature of this place. As for me, I only hope to be faithful to their truth. To achieve this, I think time has come to unveil the history of the Aures- Nememcha insurrection and rid it of its slag, reaching deep in its genuine reality which makes it fascinating. The events told here go from November 1st, 1954 to June 1959. They depict rather normal facts, sometimes mean, often grandiose, and men who discover their humanity and whose everyday life in the bush is scrutinized as if by a scanner. As it is known, it is not easy to revive part of contemporary History, particularly the one concerning the Aures Nememcha insurrection of November 1954. I have started gleaning testimonies in 1969, leaving aside those dealing with propaganda or exonerating partiality. I have confronted facts and witnesses, through an unyielding search for truth, bearing in mind that each witness, consciously or not, is victim of his own implication. -

Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change on the Agriculture Sector in the Southern Mediterranean: FORESEEN DEVELOPMENTS and POLICY MEASURES

Assessment of the impacts of Climate Change on the Agriculture Sector in the Southern Mediterranean: FORESEEN DEVELOPMENTS AND POLICY MEASURES Follow the UfM Secretariat on: ufmsecretariat @UfMSecretariat union-for-the-mediterranean February 2019 Authors: Matto Bocci and Thanos Smanis with support of Noureddine Gaaloul. The study was funded under the EU Facility to support policy dialogue on Integrated Maritime Policy / Climate Change. A DGNEAR project led by Atkins together with Pescares Italia Srl, GIZ and SML. 2 | Assessment of the impacts of Climate Change on the Agriculture Sector in the Southern Mediterranean Contents Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Setting the stage for this study ..................................................................................................................... 7 Scope and objectives of the study ............................................................................................................ 7 Background and challenges ...................................................................................................................... 8 Methodological overview ......................................................................................................................... 9 Contents of the chapters in this study ...................................................................................................... 9 Climate Change impacts on Agriculture -

Aba Nombre Circonscriptions Électoralcs Et Composition En Communes De Siéges & Pourvoir

25ame ANNEE. — N° 44 Mercredi 29 octobre 1986 Ay\j SI AS gal ABAN bic SeMo, ObVel , - TUNIGIE ABONNEMENT ANNUEL ‘ALGERIE MAROC ETRANGER DIRECTION ET REDACTION: MAURITANIE SECRETARIAT GENERAL Abonnements et publicité : Edition originale .. .. .. .. .. 100 D.A. 150 DA. Edition originale IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE et satraduction........ .. 200 D.A. 300 DA. 7 9 et 13 Av. A. Benbarek — ALGER (frais d'expédition | tg}, ; 65-18-15 a 17 — C.C.P. 3200-50 ALGER en sus) Edition originale, le numéro : 2,50 dinars ; Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 5 dinars. — Numéros des années antérleures : suivant baréme. Les tables sont fourntes gratul »ment aux abonnés. Priére dé joindre les derniéres bandes . pour renouveliement et réclamation. Changement d'adresse : ajouter 3 dinars. Tarif des insertions : 20 dinars la ligne JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX LOIS, ORDONNANCES ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, CIRCULAIRES, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANGAISE) SOMMAIRE DECRETS des ceuvres sociales au ministére de fa protection sociale, p. 1230. Décret n° 86-265 du 28 octobre 1986 déterminant les circonscriptions électorales et le nombre de Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux siéges & pourvoir pour l’élection a l’Assemblée fonctions du directeur des constructions au populaire nationale, p. 1217. , ministére de la formation professionnelle et du travail, p. 1230. DECISIONS INDIVIDUELLES Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux fonctions du directeur général da la planification Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux et de. la gestion industrielle au ministére de fonctions du directeur de la sécurité sociale et lindustrie lourde,.p. -

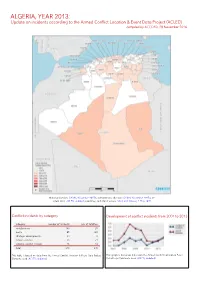

ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016

ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 28 November 2016 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2004 to 2013 category number of incidents sum of fatalities riots/protests 149 25 battle 85 282 strategic developments 34 0 remote violence 26 21 violence against civilians 16 12 total 310 340 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). ALGERIA, YEAR 2013: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 28 NOVEMBER 2016 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Adrar, 27 incidents killing 62 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Adrar, Bordj Badji Mokhtar, Ouaina, Sbaa, Tanezrouft, Tanezrouft Desert, Timiaouine, Timimoun. In Alger, 56 incidents killing 8 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Algiers, Bab El Oued, Baraki, Kouba, Said Hamdine. -

Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications

TTeerrrroorriissmm iinn NNoorrtthh AAffrriiccaa && tthhee SSaahheell iinn 22001122:: GGlloobbaall RReeaacchh && IImmpplliiccaattiioonnss Yonah Alexander SSppeecciiaall UUppddaattee RReeppoorrtt FEBRUAR Y 2013 Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Yonah Alexander Director, Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, and Senior Fellow, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies February 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Yonah Alexander. Published by the International Center for Terrorism Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced, stored or distributed without the prior written consent of the copyright holder. Manufactured in the United States of America INTER-UNIVERSITY CENTER FO R TERRORISM STUDIES Potomac Institute For Policy Studies 901 North Stuart Street Suite 200 Arlington, VA 22203 E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 703-525-0770 [email protected] www.potomacinstitute.org Terrorism in North Africa and the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach and Implications Terrorism in North Africa & the Sahel in 2012: Global Reach & Implications Table of Contents MAP-GRAPHIC: NEW TERRORISM HOTSPOT ........................................................ 2 PREFACE: TERRORISM IN NORTH AFRICA & THE SAHEL .................................... 3 PREFACE ........................................................................................................ 3 MAP-CHART: TERRORIST ATTACKS IN REGION SINCE 9/11 ....................... 3 SELECTED RECOMMENDATIONS -

Bréves De Boumerdes

Bréves de Boumerdes Don de trois centres de formation destinés aux sinistrés Les sociétés étrangères Anadarko (USA) et Maerks (Danemark), spécialisées respectivement dans l’exploitation pétrolière et le transport maritime des marchandises, ont fait un don au profit des élèves sinistrés qui n’ont pas pu poursuivre leur cycle scolaire normalement, en implantant au niveau des sites des chalets situés à Boudouaou et Corso trois centres de formation professionnelle. Ces centres, qui ont déjà ouvert leurs portes, offrent aux élèves sinistrés des cours de couture, coiffure, broderie. Le financement de ce projet, assuré par les deux entreprises étrangères susmentionnées, a été évalué à cinq milliards de centimes. 16 422 familles nécessiteuses recensées Les services de la direction de la solidarité de la wilaya de Boumerdès ont recensé au cours du mois sacré de ramadan 16 422 familles nécessiteuses. ces dernières ont bénéficié chaque jour du traditionnel couffin de ramadan. Pour ce qui est des repas chauds, les autorités locales ont ouvert dix restaurants de la rahma, qui ont assuré quotidiennement quelques 2 400 repas chauds aux passants et aux gens démunis de la région. Les élèves de Haouch El-Mokhfi en danger Aussi paradoxal que cela puisse paraître, une petite ruelle en piste et sans trottoir menant directement au CEM Haouch El-Mokhfi d’Ouled Heddadj dans la wilaya de Boumerdès est squattée par des particuliers, propriétaires d’engins poids lourds. En effet, des semi-remorques, des camions et même des bus bloquent chaque matin et durant toute la journée l’entrée principale du CEM, mettant ainsi en danger la vie de centaines d’élèves scolarisés dans cette école. -

LES MAMMIFERES SAUVAGES D'algerie Répartition Et Biologie

LES MAMMIFERES SAUVAGES D’ALGERIE Répartition et Biologie de la Conservation Mourad Ahmim To cite this version: Mourad Ahmim. LES MAMMIFERES SAUVAGES D’ALGERIE Répartition et Biologie de la Con- servation. Les Editions du Net, 2019, 978-2312068961. hal-02375326 HAL Id: hal-02375326 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02375326 Submitted on 22 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LES MAMMIFERES SAUVAGES D’ALGERIE Répartition et Biologie de la Conservation Par Mourad AHMIM SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPITRE 1 – METHODES DE TRAVAIL 1.1. Présentation de l’Algérie 3 1.2. Géographie physique de l’Algérie 3 1.2.1. Le Sahara 3 1.2.2. L’Algérie occidentale 4 1.2.3. L’Algérie orientale 4 1.3. Origine des données et présentation du catalogue 5 1.4. Critères utilisés pour la systématique 6 1.4.1. Mensurations crâniennes 6 1.4.2. Mensurations corporelles 6 1.5. Présentation du catalogue 6 1.6. Critères de classification pour la conservation 7 1.7. Catégories de la liste rouge 7 CHAPITRE 2 –EVOLUTION DES CONNAISSANCES SUR LES MAMMIFERES D’ALGERIE 2.1.