Torah Musings Digests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daat Torah (PDF)

Daat Torah Rabbi Alfred Cohen Daat Torah is a concept of supreme importance whose specific parameters remain elusive. Loosely explained, it refers to an ideology which teaches that the advice given by great Torah scholars must be followed by Jews committed to Torah observance, inasmuch as these opinions are imbued with Torah insights.1 Although the term Daat Torah is frequently invoked to buttress a given opinion or position, it is difficult to find agreement on what is actually included in the phrase. And although quite a few articles have been written about it, both pro and con, many appear to be remarkably lacking in objectivity and lax in their approach to the truth. Often they are based on secondary source and feature inflamma- tory language or an unflatttering tone; they are polemics rather than scholarship, with faulty conclusions arising from failure to check into what really was said or written by the great sages of earlier generations.2 1. Among those who have tackled the topic, see Lawrence Kaplan ("Daas Torah: A Modern Conception of Rabbinic Authority", pp. 1-60), in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, published by Jason Aronson, Inc., as part of the Orthodox Forum series which also cites numerous other sources in its footnotes; Rabbi Berel Wein, writing in the Jewish Observer, October 1994; Rabbi Avi Shafran, writing in the Jewish Observer, Dec. 1986, p.12; Jewish Observer, December 1977; Techumin VIII and XI. 2. As an example of the opinion that there either is no such thing now as Daat Torah which Jews committed to Torah are obliged to heed or, even if there is, that it has a very limited authority, see the long essay by Lawrence Kaplan in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, cited in the previous footnote. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC 2019-20 – HISTORICAL, MEDICAL and HALAKHIC PERSPECTIVES Second Edition Rabbi Prof

THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC RABBI PROF. AVRAHAM STEINBERG, MD THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC 2019-20 – HISTORICAL, MEDICAL AND HALAKHIC PERSPECTIVES Second Edition Rabbi Prof. Avraham Steinberg, MD Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Historical Background 3 a. Pandemics in the past b. The Coronavirus pandemic 3. Medical Background 5 4. Specific rulings and Halakhot 7 a. General behavior and the obligation to listen to the government and experts during a plague b. Defining plague c. Prayers, fasts and charity d. Self-endangerment of the healthcare providers – doctors, nurses, lab personnel, technicians e. Self-endangerment for experimental treatment and discovering a vaccine f. Prayer with a minyan, nesiyat kapayim, Torah reading, yeshivot g. Ha'gomel Blessing h. Shabbat and festivals i. Passover j. Sefirat Ha'omer k. Rosh Hashanah l. Yom Kippur m. Purim n. Immersion in the mikvah o. Immersion of utensils p. Visiting the sick q. Circumcision r. Marriage s. Burial t. Mourning 5. Triage in treating coronavirus patients during severe shortage 32 a. Introduction b. Determining triage priority in various situations when there are insufficient resources I am greatly indebted to Rabbi Dr. Jason Weiner for the English translation & to Dr. Lazar Friedman for his editorial work. 1 THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC RABBI PROF. AVRAHAM STEINBERG, MD c. Halakhic sources on determining lifesaving triage d. Halakhic guidelines on determining priority 6. Miscellaneous 40 7. Conclusion 41 1. Introduction In the modern era, the coronavirus1 pandemic2 has been the most shocking pandemic to the entire world, including experts and scientists, since the Spanish influenza pandemic 100 years ago.3 In recent decades many scientists have arrogantly claimed that in the modern and technologically advanced world there will be no more global pandemics of this sort. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

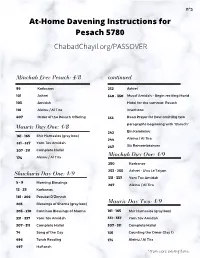

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Torah Weekly

ב ס ״ ד Torah All the Mitzvos in Ki Teitzei concludes with the material world, it is confronted obligation to remember “what by challenges that may require Weekly Parshat Ki Teitzei Amalek did to you on the road, it to engage in battle. Seventy-four of the Torah’s on your way out of Egypt. For there are two aspects to August 15-21 2021 613 commandments (mitzvot) material existence. Our world 7 Elul – 13 Elul, 5781 are in the Parshah of Ki Teitzei. was created because G-d Torah Reading: These include the laws of the “desired a dwelling in the lower Ki Teitzei: Deuteronomy 21:10 - beautiful captive, the War and Peace: Will a worlds,” i.e., the physical 26:19 inheritance rights of the Haftarah: Dove Grow Claws? universe can serve as a dwelling Isaiah 54:1-54:10 firstborn, the wayward and for G-d, a place where His rebellious son, burial and Every day, we conclude essence is revealed. But as the dignity of the dead, returning a the Shemoneh Esreh prayers by term “lower worlds” implies, PARSHAT Ki Teitzei praising G-d “who blesses His lost object, sending away the G-d’s existence is not readily We have Jewish mother bird before taking her people Israel with peace.” And apparent in our environment. when describing the Calendars. If you young, the duty to erect a safety On the contrary, the material would like one, fence around the roof of one’s blessings G-d will bestow upon nature of the world appears to please send us a home, and the various forms of us if we follow His will, our preclude holiness. -

Pandemic Passover 2.0 Answer to This Question

Food for homeless – page 2 Challah for survivors – page 3 Mikvah Shoshana never closed – page 8 Moving Rabbis – page 10 March 17, 2021 / Nisan 4, 5781 Volume 56, Issue 7 See Marking one year Passover of pandemic life Events March 16, 2020, marks the day that our schools and buildings closed last year, and our lives were and drastically changed by the reality of COVID-19 reaching Oregon. As Resources the soundtrack of the musical “Rent” put it: ~ pages Congregation Beth Israel clergy meet via Zoom using “525,600 minutes, how 6-7 CBI Passover Zoom backgrounds, a collection of which do you measure a year?” can be downloaded at bethisrael-pdx.org/passover. Living according to the Jewish calendar provides us with one Pandemic Passover 2.0 answer to this question. BY DEBORAH MOON who live far away. We measure our year by Passover will be the first major Congregation Shaarie Torah Exec- completing the full cycle Jewish holiday that will be celebrated utive Director Jemi Kostiner Mansfield of holidays and Jewish for the second time under pandemic noticed the same advantage: “Families rituals. Time and our restrictions. and friends from out of town can come need for our community Since Pesach is traditionally home- together on a virtual platform, people and these rituals haven’t stopped in this year, even based, it is perhaps the easiest Jewish who normally wouldn’t be around the though so many of our usual ways of marking these holiday to adapt to our new landscape. seder table.” holy moments have been interrupted. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Radicalization of the Settlers' Youth: Hebron As a Hub for Jewish Extremism

© 2014, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 69-85 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) Radicalization of the Settlers’ Youth: Hebron as a Hub for Jewish Extremism Geneviève Boucher Boudreau University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract: The city of Hebron has been a hub for radicalization and terrorism throughout the modern history of Israel. This paper examines the past trends of radicalization and terrorism in Hebron and explains why it is still a present and rising ideology within the Jewish communities and organization such as the Hilltop Youth movement. The research first presents the transmission of social memory through memorials and symbolism of the Hebron hills area and then presents the impact of Meir Kahana’s movement. As observed, Hebron slowly grew and spread its population and philosophy to the then new settlement of Kiryat Arba. An exceptionally strong ideology of an extreme form of Judaism grew out of those two small towns. As analyzed—based on an exhaustive ethnographic fieldwork and bibliographic research—this form of fundamentalism and national-religious point of view gave birth to a new uprising of violence and radicalism amongst the settler youth organizations such as the Hilltop Youth movement. Keywords: Judaism; Radicalization; Settlers; Terrorism; West Bank Geneviève Boucher Boudreau 70 Résumé: Dès le début de l’histoire moderne de l’État d’Israël, les villes d’Hébron et Kiryat Arba sont devenues une plaque tournante pour la radicalisation et le terrorisme en Cisjordanie. Cette recherche examine cette tendance, explique pourquoi elle est toujours d’actualité ainsi qu’à la hausse au sein de ces communautés juives. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Cincinnati Torah הרות

בס"ד • A PROJECT OF THE CINCINNATI COMMUNITY KOLLEL • CINCYKOLLEL.ORG תורה מסינסי Cincinnati Torah Vol. VI, No. XXXVIII Eikev A LESSON FROM A TIMELY HALACHA THE PARASHA RABBI YITZCHOK PREIS RABBI CHAIM HEINEMANN OUR PARASHA INCLUDES THE BIBLICAL MITZVAH human nature and how each of these mitzvahs A common question that comes up during to thank Hashem after eating a satisfying is designed to protect us from a potential hu- bein hazmanim and summer break is meal—the blessings we typically refer to as man failing. whether it is appropriate to remove one’s bentching or Birkat Hamazon. A spiritual hazard looms immediately fol- tallis katan (or tzitzis) while playing sports or The Talmud suggests that, logically, if we lowing a satisfying meal. Prior to eating, while engaging in strenuous activities that make are obligated to bless Hashem after eating, hungry, it easy to sense our dependency on one hot and sweaty. kal vachomer (all the more so), we should be our Provider. But once satisfying that hunger, While it is true that neither Biblical nor expected to recite a bracha before eating. After our attitude can shift. We run the risk of Rabbinic law obligates one to wear a all, someone who is famished is more acutely becoming self-assured, confident in our own tallis katan at all times, it has become the aware of the need for food and more appre- sustenance, and potentially dismissive of the accepted custom that every male wears a ciative that Hashem has made it available to True Source of satiation. Bentching protects tallis katan all day long. -

Prager-Shabbat-Morning-Siddur.Pdf

r1'13~'~tp~ N~:-t ~'!~ Ntf1~P 1~n: CW? '?¥ '~i?? 1~~T~~ 1~~~ '~~:} 'tZJ... :-ttli3i.. -·. n,~~- . - .... ... For the sake of the union of the Holy One Blessed Be He, and the Shekhinah I am prepared to take upon myself the mitzvah You Shall Love Your Fellow Person as Yourself V'ahavta l'rey-acha kamocha and by this merit I open my mouth. .I ....................... ·· ./.· ~ I The P'nai Or Shabbat Morning Siddur Second Edition Completed, with Heaven's Aid, during the final days of the count of the Orner, 5769. "Prayer can be electric and alive! Prayer can touch the soul, burst forth a creative celebration of the spirit and open deep wells of gratitude, longing and praise. Prayer can connect us to our Living Source and to each other, enfolding us in love and praise, wonder and gratitude, awe and thankfulness. Jewish prayer in its essence is soul dialogue and calls us into relationship within and beyond. Through the power of words and melodies both ancient and new, we venture into realms of deep emotion and find longing, sorrow ,joy, hope, wholeness, connection and peace. When guided by skilled leaders of prayer and ritual, our complacency is challenged. We break through outworn assumptions about God and ourselves, and emerge refreshed and inspired to meet the challenges OUr lives offer." (-from the DLTI brochure, by Rabbis Marcia Prager and Shawn Israel Zevit) This Siddur was created as a vehicle to explore how traditional and novel approaches to Jewish prayer can blend, so that the experience of Jewish prayer can be renewed, revitalized and deepened. -

The Laws and Customs of Mourning

COMFORTING THE MOURNERS The Laws and Customs of Mourning Compiled by Rabbi Zalman Manela Table Of Contents A Letter of Consolation ................................................................................................................................. 2 Before the Burial ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Burial Preparations ....................................................................................................................................... 5 The Funeral ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Honoring the Deceased................................................................................................................................. 6 Burial ............................................................................................................................................................. 6 After the Burial .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Tearing the Garments ................................................................................................................................... 7 The First Meal ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Praying and Saying Kaddish