Winter Cropping in Ficus Tinctoria: an Alternative Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Check List of Wild Angiosperms of Bhagwan Mahavir (Molem

Check List 9(2): 186–207, 2013 © 2013 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Check List of Wild Angiosperms of Bhagwan Mahavir PECIES S OF Mandar Nilkanth Datar 1* and P. Lakshminarasimhan 2 ISTS L (Molem) National Park, Goa, India *1 CorrespondingAgharkar Research author Institute, E-mail: G. [email protected] G. Agarkar Road, Pune - 411 004. Maharashtra, India. 2 Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India, P. O. Botanic Garden, Howrah - 711 103. West Bengal, India. Abstract: Bhagwan Mahavir (Molem) National Park, the only National park in Goa, was evaluated for it’s diversity of Angiosperms. A total number of 721 wild species belonging to 119 families were documented from this protected area of which 126 are endemics. A checklist of these species is provided here. Introduction in the National Park are Laterite and Deccan trap Basalt Protected areas are most important in many ways for (Naik, 1995). Soil in most places of the National Park area conservation of biodiversity. Worldwide there are 102,102 is laterite of high and low level type formed by natural Protected Areas covering 18.8 million km2 metamorphosis and degradation of undulation rocks. network of 660 Protected Areas including 99 National Minerals like bauxite, iron and manganese are obtained Parks, 514 Wildlife Sanctuaries, 43 Conservation. India Reserves has a from these soils. The general climate of the area is tropical and 4 Community Reserves covering a total of 158,373 km2 with high percentage of humidity throughout the year. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 503 the Vascular Plants Of

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 503 THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS BY NANCY VANDER VELDE ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, D.C., U.S.A. AUGUST 2003 Uliga Figure 1. Majuro Atoll THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF MAJURO ATOLL, REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS ABSTRACT Majuro Atoll has been a center of activity for the Marshall Islands since 1944 and is now the major population center and port of entry for the country. Previous to the accompanying study, no thorough documentation has been made of the vascular plants of Majuro Atoll. There were only reports that were either part of much larger discussions on the entire Micronesian region or the Marshall Islands as a whole, and were of a very limited scope. Previous reports by Fosberg, Sachet & Oliver (1979, 1982, 1987) presented only 115 vascular plants on Majuro Atoll. In this study, 563 vascular plants have been recorded on Majuro. INTRODUCTION The accompanying report presents a complete flora of Majuro Atoll, which has never been done before. It includes a listing of all species, notation as to origin (i.e. indigenous, aboriginal introduction, recent introduction), as well as the original range of each. The major synonyms are also listed. For almost all, English common names are presented. Marshallese names are given, where these were found, and spelled according to the current spelling system, aside from limitations in diacritic markings. A brief notation of location is given for many of the species. The entire list of 563 plants is provided to give the people a means of gaining a better understanding of the nature of the plants of Majuro Atoll. -

Weiblen, G.D. 2002 How to Be a Fig Wasp. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 47:299

25 Oct 2001 17:34 AR ar147-11.tex ar147-11.sgm ARv2(2001/05/10) P1: GJB Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002. 47:299–330 Copyright c 2002 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved ! HOW TO BE A FIG WASP George D. Weiblen University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Biology, St. Paul, Minnesota 55108; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words Agaonidae, coevolution, cospeciation, parasitism, pollination ■ Abstract In the two decades since Janzen described how to be a fig, more than 200 papers have appeared on fig wasps (Agaonidae) and their host plants (Ficus spp., Moraceae). Fig pollination is now widely regarded as a model system for the study of coevolved mutualism, and earlier reviews have focused on the evolution of resource conflicts between pollinating fig wasps, their hosts, and their parasites. Fig wasps have also been a focus of research on sex ratio evolution, the evolution of virulence, coevolu- tion, population genetics, host-parasitoid interactions, community ecology, historical biogeography, and conservation biology. This new synthesis of fig wasp research at- tempts to integrate recent contributions with the older literature and to promote research on diverse topics ranging from behavioral ecology to molecular evolution. CONTENTS INTRODUCING FIG WASPS ...........................................300 FIG WASP ECOLOGY .................................................302 Pollination Ecology ..................................................303 Host Specificity .....................................................304 Host Utilization .....................................................305 -

I Is the Sunda-Sahul Floristic Exchange Ongoing?

Is the Sunda-Sahul floristic exchange ongoing? A study of distributions, functional traits, climate and landscape genomics to investigate the invasion in Australian rainforests By Jia-Yee Samantha Yap Bachelor of Biotechnology Hons. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation i Abstract Australian rainforests are of mixed biogeographical histories, resulting from the collision between Sahul (Australia) and Sunda shelves that led to extensive immigration of rainforest lineages with Sunda ancestry to Australia. Although comprehensive fossil records and molecular phylogenies distinguish between the Sunda and Sahul floristic elements, species distributions, functional traits or landscape dynamics have not been used to distinguish between the two elements in the Australian rainforest flora. The overall aim of this study was to investigate both Sunda and Sahul components in the Australian rainforest flora by (1) exploring their continental-wide distributional patterns and observing how functional characteristics and environmental preferences determine these patterns, (2) investigating continental-wide genomic diversities and distances of multiple species and measuring local species accumulation rates across multiple sites to observe whether past biotic exchange left detectable and consistent patterns in the rainforest flora, (3) coupling genomic data and species distribution models of lineages of known Sunda and Sahul ancestry to examine landscape-level dynamics and habitat preferences to relate to the impact of historical processes. First, the continental distributions of rainforest woody representatives that could be ascribed to Sahul (795 species) and Sunda origins (604 species) and their dispersal and persistence characteristics and key functional characteristics (leaf size, fruit size, wood density and maximum height at maturity) of were compared. -

The Vascular Plants of the Horne and Wallis Islands' HAROLD ST

The Vascular Plants of the Horne and Wallis Islands' HAROLD ST. JOHN2 AND ALBERT C. SMITHs ABSTRACT: Recent botanical collections by H. S. McKee and Douglas E. Yen, together with the few available records from published papers, have been collated into a checklist of the known vascular plants of the Horne and Wallis Islands. Of 248 species here listed, 170 appear to be indigenous. Many of these are widespread, but 45 of them are limited to the Fijian Region (New Hebrides to Samoa) . Of the four known endemic species, Elatostema yenii St. John and Peperomia fllttmaensis St. John are herewith proposed as new, and a new combination in the fern genus Tbelypteris, by G. Brownlie, is included. THE HORNE AND WALLIS ISLANDS, forming Alofi, and Uvea, and it seems pertinent to bring the French Protectorat des Iles Wallis et Futuna, together the available data on the vascular plants lie to the northeast of Fiji, due west of Samoa, of the area. In the present treatment all the and due east of Rotuma. The Horne Islands in specimens obtained by McKee and Yen are clude Futuna (with about 25 square miles) and cited, and we also include as many Burrows Alofi (with about 11 square miles) , lying some specimens as could be located in the herbarium 150 miles northeast of Vanua Levu and about of the Bishop Museum. We have also listed 100 miles southwest of Uvea. Both Futuna and several species for which no herbarium vouch Alofi are high islands with fringing coral reefs; ers are at hand. These latter records are included the former attains an elevation of about 760 m on the basis of apparently reliable reports of in Mt. -

The Occurrence of Fig Wasps in the Fruits of Female Gynodioecious Fig

Acta Oecologica 46 (2013) 33e38 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Acta Oecologica journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actoec Original article The occurrence of fig wasps in the fruits of female gynodioecious fig trees Tao Wu a,c, Derek W. Dunn b, Hao-Yuan Hu a, Li-Ming Niu a, Jin-Hua Xiao a, Xian-Li Pan c, Gui Feng a, Yue-Guan Fu d, Da-Wei Huang a,e,* a Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China b School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, UK c College of Environment and Plant Protection, Hainan University, Danzhou, Hainan 571737, China d Environment and Plant Protection Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Danzhou, Hainan 571737, China e College of Plant Protection, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, Shandong 271018, China article info abstract Article history: Fig trees are pollinated by wasp mutualists, whose larvae consume some of the plant’s ovaries. Many fig Received 15 December 2011 species (350þ) are gynodioecious, whereby pollinators generally develop in the figs of ‘male’ trees and Accepted 29 October 2012 seeds generally in the ‘females.’ Pollinators usually cannot reproduce in ‘female’ figs at all because their Available online 28 November 2012 ovipositors cannot penetrate the long flower styles to gall the ovaries. Many non-pollinating fig wasp (NPFW) species also only reproduce in figs. These wasps can be either phytophagous gallers or parasites Keywords: of other wasps. The lack of pollinators in female figs may thus constrain or benefit different NPFWs Non-pollinating figwasp through host absence or relaxed competition. -

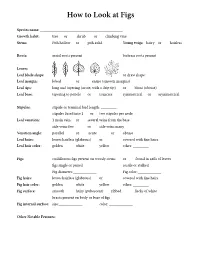

How to Look at Figs

How to Look at Figs Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub or climbing vine Stems: Pith hollow or pith solid Young twigs: hairy or hairless Roots: aerial roots present buttress roots present Leaves Leaf blade shape: or draw shape: Leaf margin: lobed or entire (smooth margins) Leaf tips: long and tapering (acute, with a drip tip) or blunt (obtuse) Leaf base: tapering to petiole or truncate symmetrical or asymmetrical Stipules: stipule or terminal bud length: ________ stipules fused into 1 or two stipules per node Leaf venation: 1 main vein or several veins from the base side veins few or side veins many Venation angle: parallel or acute or obtuse Leaf hairs: leaves hairless (glabrous) or covered with fne hairs Leaf hair color: golden white yellow other: ________ Figs cauliforous fgs present on woody stems or found in axils of leaves fgs single or paired sessile or stalked Fig diameter:____________ Fig color:____________ Fig hairs: leaves hairless (glabrous) or covered with fne hairs Fig hair color: golden white yellow other: ________ Fig surface: smooth hairy (pubescent) ribbed fecks of white bracts present on body or base of fgs Fig internal surface: size:____________ color: ____________ Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Ficus Family: Moraceae Genus Ficus = ~850 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 1059. 1753 Subgenera and examples of commonly grown species: Subgenus Ficus (~350 species) Africa, Asia, Australasia, Mediterranean Mostly gynodioecious, no bracts among the fowers, free standing trees and shrubs, cauliforous or not, pollination passive Ficus carica L. – common fg Ficus deltoidea Jack – mistletoe fg Subgenus Sycidium (~100 species) Africa, Asia, Australasia Mostly gynodioecious, no bracts among the fowers, free standing trees and shrubs, cauliforous or not, pollination passive Ficus coronata Spin - creek sandpaper fg Ficus fraseri Miq. -

Ericaceae in Malesia: Vicariance Biogeography, Terrane Tectonics and Ecology

311 Ericaceae in Malesia: vicariance biogeography, terrane tectonics and ecology Michael Heads Abstract Heads, Michael (Science Faculty, University of Goroka, PO Box 1078, Goroka, Papua New Guinea. Current address: Biology Department, University of the South Pacific, P.O. Box 1168, Suva, Fiji. Email: [email protected]) 2003. Ericaceae in Malesia: vicariance biogeography, terrane tectonics and ecology. Telopea 10(1): 311–449. The Ericaceae are cosmopolitan but the main clades have well-marked centres of diversity and endemism in different parts of the world. Erica and its relatives, the heaths, are mainly in South Africa, while their sister group, Rhododendron and relatives, has centres of diversity in N Burma/SW China and New Guinea, giving an Indian Ocean affinity. The Vaccinioideae are largely Pacific-based, and epacrids are mainly in Australasia. The different centres, and trans-Indian, trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic Ocean disjunctions all indicate origin by vicariance. The different main massings are reflected in the different distributions of the subfamilies within Malesia. With respect to plant architecture, in Rhododendron inflorescence bracts and leaves are very different. Erica and relatives with the ‘ericoid’ habit have similar leaves and bracts, and the individual plants may be homologous with inflorescences of Rhododendron. Furthermore, in the ericoids the ‘inflorescence-plant’ has also been largely sterilised, leaving shoots with mainly just bracts, and flowers restricted to distal parts of the shoot. The epacrids are also ‘inflorescence-plants’ with foliage comprised of ‘bracts’, but their sister group, the Vaccinioideae, have dimorphic foliage (leaves and bracts). In Malesian Ericaceae, the four large genera and the family as a whole have most species in the 1500–2000 m altitudinal belt, lower than is often thought and within the range of sweet potato cultivation. -

MORACEAE Genera Other Than FICUS (C.C

Flora Malesiana, Series I, Volume 17 / Part 1 (2006) 1–152 MORACEAE GENera OTHer THAN FICUS (C.C. Berg, E.J.H. Corner† & F.M. Jarrett)1 FOREWORD The following treatments of Artocarpus, Hullettia, Parartocarpus, and Prainea are based on the monograph by Jarrett (1959–1960) and on the treatments she made for this Flora in cooperation with Dr. M. Jacobs in the 1970s. These included some new Artocarpus species described in 1975 and the re-instatement of A. peltata. Artocarpus lanceifolius subsp. clementis was reduced to the species, in A. nitidus the subspe- cies borneensis and griffithii were reduced to varieties and the subspecies humilis and lingnanensis included in var. nitidus. The varieties of A. vrieseanus were no longer recognised. More new Malesian species of Parartocarpus were described by Corner (1976), Go (1998), and in Artocarpus by Kochummen (1998). A manuscript with the treatment of the other genera was submitted by Corner in 1972. Numerous changes to the taxonomy, descriptions, and keys have been made to the original manuscripts, for which the present first author is fully responsible. References: Corner, E.J.H., A new species of Parartocarpus Baillon (Moraceae). Gard. Bull. Singa- pore 28 (1976) 183–190. — Go, R., A new species of Parartocarpus (Moraceae) from Sabah. Sandaka- nia 12 (1998) 1–5. — Jarrett, F.M., Studies in Artocarpus and allied genera I–V. J. Arnold Arbor. 50 (1959) 1–37, 113–155, 298–368; 51 (1960) 73–140, 320–340. — Jarrett, F.M., Four new Artocarpus species from Indo-Malesia (Moraceae). Blumea 22 (1975) 409–410. — Kochummen, K.M., New species and varieties of Moraceae from Malaysia. -

Tropical Plant List F

Tropical Plant List F Pages loading too slowly! Click here to transfer to a less intensively visual version of this Online Catalogue for faster browsing! Homepage Online Catalog Plants in Limited Supply Garden Arts Gallery Fine Arts Gallery Site Map Show your discount. Plan for your Fall/Winter Click Here to Go to the next set of Plants in this alphabetical list of Tropical Plants! A selection of TROPICALS, some in very limited supply, covering the letter "F" This page contains the following plant groups: Fatshedera (Tree Ivy), Felicia (Vining Blue Daisy), Ficus (Fig Tree), Fittonia (Nerve Plant), Fortunella, Fosterella, Fuchsia. http://www.glasshouseworks.com/trop-f.html (1 of 22) [12/20/2009 9:50:04 PM] Tropical Plant List F You can use our new Shopping Cart by filling in the number of plants needed below and clicking on the "Order Now" button anywhere on our catalogue pages to the left of the plant entry. Our new Shopping Cart is the easiest way to order. After you have ordered your last selection, just follow the directions on the Shopping Cart page. You can order this way from any of our catalogue pages, wherever you see the "Order Now" button. If the Shopping Cart does not work, just click the "Fill In the Online Orderform" button above. 40501 FATSHEDERA LIZEI PIA ARAL HP PRICE: $4.75 "Curly Tree Ivy" Also often called "Botanical Wonder: for it is a hybrid of Aralia and Hedera. Star-shaped leaves deeply fluted (sometimes listed as F. undulata) on erect semi-woody stems. Tolerates considerable chill. -

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India

RESEARCH Vol. 21, Issue 68, 2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE ISSN 2319–5746 EISSN 2319–5754 Species Floristic Diversity and Analysis of South Andaman Islands (South Andaman District), Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India Mudavath Chennakesavulu Naik1, Lal Ji Singh1, Ganeshaiah KN2 1Botanical Survey of India, Andaman & Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair-744102, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India 2Dept of Forestry and Environmental Sciences, School of Ecology and Conservation, G.K.V.K, UASB, Bangalore-560065, India Corresponding author: Botanical Survey of India, Andaman & Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair-744102, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India Email: [email protected] Article History Received: 01 October 2020 Accepted: 17 November 2020 Published: November 2020 Citation Mudavath Chennakesavulu Naik, Lal Ji Singh, Ganeshaiah KN. Floristic Diversity and Analysis of South Andaman Islands (South Andaman District), Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India. Species, 2020, 21(68), 343-409 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. ABSTRACT After 7 years of intensive explorations during 2013-2020 in South Andaman Islands, we recorded a total of 1376 wild and naturalized vascular plant taxa representing 1364 species belonging to 701 genera and 153 families, of which 95% of the taxa are based on primary collections. Of the 319 endemic species of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 111 species are located in South Andaman Islands and 35 of them strict endemics to this region. 343 Page Key words: Vascular Plant Diversity, Floristic Analysis, Endemcity. © 2020 Discovery Publication. All Rights Reserved. www.discoveryjournals.org OPEN ACCESS RESEARCH ARTICLE 1.