Kurds – “External” and “Internal” in Syria, Khaibun’S Organization and “Arab Security Belt” (Security Belt Forces)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45 the RESURRECTION of SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS by Ro

THE RESURRECTION OF SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS By Rodi Hevian* This article examines the current political landscape of the Kurdish region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played in the ongoing Syrian civil war, and intra-Kurdish relations. For many years, the Kurds in Syria were Iraqi Kurdistan to Afrin in the northwest on subjected to discrimination at the hands of the the Turkish border. This article examines the Ba’th regime and were stripped of their basic current political landscape of the Kurdish rights.1 During the 1960s and 1970s, some region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played Syrian Kurds were deprived of citizenship, in the ongoing conflict, and intra-Kurdish leaving them with no legal status in the relations. country.2 Although Syria was a key player in the modern Kurdish struggle against Turkey and Iraq, its policies toward the Kurds there THE KURDS IN SYRIA were in many cases worse than those in the neighboring countries. On the one hand, the It is estimated that there are some 3 million Asad regime provided safe haven for the Kurds in Syria, constituting 13 percent of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syria’s 23 million inhabitants. They mostly Kurdish movements in Iraq fighting Saddam’s occupy the northern part of the country, a regime. On the other hand, it cracked down on region that borders with Iraqi Kurdistan to the its own Kurds in the northern part of the east and Turkey to the north and west. There country. Kurdish parties, Kurdish language, are also some major districts in Aleppo and Kurdish culture and Kurdish names were Damascus that are populated by the Kurds. -

Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 414 SEPTEMBER 2019 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019 • TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... • TURKEY: MANY DEMONSTRATIONS AFTER FURTHER DISMISSALS OF HDP MAYORS • ROJAVA: TURKEY CONTINUES ITS THREATS • IRAQ: A CONSTITUTION FOR THE KURDISTAN REGION? • IRAN: HIGHLY CONTESTED, THE REGIME IS AGAIN STEPPING UP ITS REPRESSION TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... he Turkish govern- economist. The vice-president of ten points lower than the previ- ment is increasingly the CHP, Aykut Erdoğdu, ous year, with the disagreement embarrassed by the recalled that the Istanbul rate rising from 38 to 48%. On economic situation. Chamber of Commerce had esti- 16, TurkStat published unem- T The TurkStat Statistical mated annual inflation at ployment figures for June: 13%, Institute reported on 2 22.55%. The figure of the trade up 2.8%, or 4,253,000 unem- September that production in the union Türk-İş is almost identical. ployed. For young people aged previous quarter fell by 1.5% HDP MP Garo Paylan ironically 15 to 24, it is 24.8%, an increase compared to the same period in said: “Mr. -

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020

Kurdish Political and Civil Movements in Syria and the Question of Representation Dr Mohamad Hasan December 2020 KurdishLegitimacy Political and and Citizenship Civil Movements in inthe Syria Arab World This publication is also available in Arabic under the title: ُ ف الحركات السياسية والمدنية الكردية ي� سوريا وإشكالية التمثيل This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. For questions and communication please email: [email protected] Cover photo: A group of Syrian Kurds celebrate Newroz 2007 in Afrin, source: www.tirejafrin.com The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author and the LSE Conflict Research Programme should be credited, with the name and date of the publication. All rights reserved © LSE 2020. About Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World Legitimacy and Citizenship in the Arab World is a project within the Civil Society and Conflict Research Unit at the London School of Economics. The project looks into the gap in understanding legitimacy between external policy-makers, who are more likely to hold a procedural notion of legitimacy, and local citizens who have a more substantive conception, based on their lived experiences. Moreover, external policymakers often assume that conflicts in the Arab world are caused by deep- seated divisions usually expressed in terms of exclusive identities. -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

NGO Shadow Report for the Review of the SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC

NGO shadow report for the review of THE SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Under the UN Convention against Torture [CAT] Submitted by: International Support Kurds in Syria Association – SKS [April 2010] About SKS: International Support Kurds in Syria Association - SKS was formed in September 2009 and is based in UK. Kurds in Syria experience continuing and increasing denial of universal basic human rights, and active and intentional torture, and inhuman and degrading treatment whilst living in their ancient homelands. We aim to work in collaboration with individuals and organisations to bring about change for Kurds from Syria until universal human rights are respected. Introduction: This report focuses upon differing examples of the treatment of Kurds in Syria by the authorities, to demonstrate that the Syrian Arab Republic has intentionally continued to use torture, and inhuman and degrading treatment against its Kurdish population, despite having signed the UN Convention against Torture, and that this behaviour adversely affects Kurds in all aspects of their day-to-day lives. We are grateful to Kurdish Human Rights Watch [KHRP] and others for bringing this session to our attention, very recently. We have seen the report of KHRP and will not repeat evidence contained therein. Summary: 1) Kurds in Syria suffer torture, inhuman and degrading treatment in detention and in their everyday lives. The military and political security authorities wilfully take advantage of the State of Emergency and martial law to make arbitrary arrests and detentions without trial, in order to oppress and suppress human rights defenders and the Kurdish population. We know that acts of severe pain and suffering are intentionally and frequently inflicted on Kurds in Syria with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. -

The Thistle and the Drone

AKBAR AHMED HOW AMERICA’S WAR ON TERROR BECAME A GLOBAL WAR ON TRIBAL ISLAM n the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the United States declared war on terrorism. More than ten years later, the results are decidedly mixed. Here world-renowned author, diplomat, and scholar Akbar Ahmed reveals an important yet largely ignored result of this war: in many nations it has exacerbated the already broken relationship between central I governments and the largely rural Muslim tribal societies on the peripheries of both Muslim and non-Muslim nations. The center and the periphery are engaged in a mutually destructive civil war across the globe, a conflict that has been intensified by the war on terror. Conflicts between governments and tribal societies predate the war on terror in many regions, from South Asia to the Middle East to North Africa, pitting those in the centers of power against those who live in the outlying provinces. Akbar Ahmed’s unique study demonstrates that this conflict between the center and the periphery has entered a new and dangerous stage with U.S. involvement after 9/11 and the deployment of drones, in the hunt for al Qaeda, threatening the very existence of many tribal societies. American firepower and its vast anti-terror network have turned the war on terror into a global war on tribal Islam. And too often the victims are innocent children at school, women in their homes, workers simply trying to earn a living, and worshipers in their mosques. Bat- tered by military attacks or drone strikes one day and suicide bombers the next, the tribes bemoan, “Every day is like 9/11 for us.” In The Thistle and the Drone, the third vol- ume in Ahmed’s groundbreaking trilogy examin- ing relations between America and the Muslim world, the author draws on forty case studies representing the global span of Islam to demon- strate how the U.S. -

Sdf's Arab Majority Rank Turkey As the Biggest

SDF’S ARAB MAJORITY RANK TURKEY AS THE BIGGEST THREAT TO NE SYRIA. Survey Data on America’s Partner Forces Amy Austin Holmes 2 0 1 9 Arab women from Deir Ezzor who joined the SDF after living under the Islamic State Of all the actors in the Syrian conflict, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) are perhaps the most misunderstood party. Five years after the United States decided to partner with the SDF, gaping holes remain in our knowledge about the women and men who defeated the Islamic State (IS). In order to remedy the knowledge gap, I conducted the first field survey of the Syrian Democratic Forces. Through multiple visits to all of the governorates of Northeastern Syria under SDF control, I have generated new and unprecedented data, which can offer policy guidance as the United States must make decisions about how to move forward in the post-caliphate era. There are a number of reasons for the current lack of substantive information on the SDF. First, the SDF has been in a state of constant expansion ever since it was created, pro- gressively recruiting more people and capturing more territory. And, as a non-state actor, the SDF lacks the bureaucracy of national armies. Defeating the Islamic State was their priority, not collecting statistics. The SDF’s low media profile has also played a role. Perhaps wary of their status as militia leaders, high-ranking commanders have been reticent to give interviews. Recently, Gen- eral Mazlum Kobani, the Kurdish commander-in-chief of the SDF, has conducted a few interviews.1 And even less is known about the group’s rank-and-file troops. -

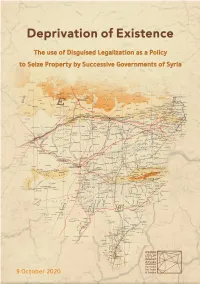

In PDF Format, Please Click Here

Deprivatio of Existence The use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds Acknowledgment and Gratitude The present report is the result of a joint cooperation that extended from 2018’s second half until August 2020, and it could not have been produced without the invaluable assistance of witnesses and victims who had the courage to provide us with official doc- uments proving ownership of their seized property. This report is to be added to researches, books, articles and efforts made to address the subject therein over the past decades, by Syrian/Kurdish human rights organizations, Deprivatio of Existence individuals, male and female researchers and parties of the Kurdish movement in Syria. Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) would like to thank all researchers who contributed to documenting and recording testimonies together with the editors who worked hard to produce this first edition, which is open for amendments and updates if new credible information is made available. To give feedback or send corrections or any additional documents supporting any part of this report, please contact us on [email protected] About Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) STJ started as a humble project to tell the stories of Syrians experiencing enforced disap- pearances and torture, it grew into an established organization committed to unveiling human rights violations of all sorts committed by all parties to the conflict. Convinced that the diversity that has historically defined Syria is a wealth, our team of researchers and volunteers works with dedication at uncovering human rights violations committed in Syria, regardless of their perpetrator and victims, in order to promote inclusiveness and ensure that all Syrians are represented, and their rights fulfilled. -

Could the Arab Belt Issue Resurface in Northeast Syria?

Help . About Us . Contact Us . Site Map . Advertise with Syria Report . Terms & Conditions Page 1 of 2 Could the Arab Belt Issue Resurface in Northeast Syria? 17-02-2021 On January 28, judicial authorities in northeastern Syria issued a potentially problematic decree prohibiting certain lawsuits related to real estate in lands under their purview. The Social Justice Council, which is the judicial authority in the Autonomous Administration in North and East Syria (AANES), issued Decree No. 6, barring its justice bureaus—functionally, its courts—from hearing real estate rights cases related to the origin of rights for certain lands located outside of official zoning plans. Origin of rights cases deal with protecting ownership rights and other real estate rights. Real estate rights are typically the right of ownership and disposal, surface right, right of utilisation, documentation, and confirmation of sales contracts. In other words, the council forbade the bureaus from deciding on lawsuits related to so-called “Amiri lands,” and demanded that courts dismiss cases related to real rights. Amiri lands are properties legally owned by the state, though occupants have the right to sell or lease them under Article 86 of the Syrian Civil Code. The council also obligated courts to revert Amiri lands and state ownership issues to their pre-2013 legal status; 2013 is the year that the AANES was formed. The decree also forbade courts from looking into real estate cases related to the origin of rights which had previously been considered and decided by a court decision, regardless of the authority that issued it. The decree also ruled that the justice bureaus cannot hear possession claims over state properties, except after obtaining permission or a rental contract from the relevant administrative authority. -

Zürcher Beiträge Zur Sicherheitspolitik Und Konfliktforschung

Nr. 70 70 ZB Nr. ZB Nr. Zürcher Beiträge zur Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktforschung Doron Zimmermann � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �� � � � � � The Center for Security Studies, part of the ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Tangled Skein Institute of Technology), was founded in 1986 and specializes in interna- tional relations and security policy. It runs the International Relations and or Gordian Knot? Security Network (ISN) electronic platform and is developing the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA). The Center also runs the Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Management Network (CRN), the Swiss Foreign and Security Policy Network (SSN), and the Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact (PHP). The Center for Security Studies is a mem- ber of the Center for Comparative and International Studies (CIS), which is Iran and Syria as State Supporters a joint initiative between the ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich, and of Political Violence Movements specializes in comparative politics and international relations. in Lebanon and in the Palestinian Zürcher Beiträge zur Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktforschung Territories This publication series comprises individual monographs that cover Swiss foreign and security policy, international security policy, and conflict research. The monographs are based on a broad understanding of security that Hrsg.: Andreas Wenger encompasses military, political, economic, social, and ecological dimensions. The monographs are published in German, English, or French. Electronic -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Syria Over a 20-Year Period

SYRIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE REPORT ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN SYRIA OVER A 20-YEAR PERIOD 1979-1999 Copyright ©2001 by Syrian Human Rights Committee(SHRC) No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or translated in any form or by any means, electronics, mechanical, manual, optical or otherwise, withought the priror written permission of SHRC. July 2001, First Edition. Not available on hardcopy format, but the full report can be downloaded from SHRC web site on http://www.shrc.org Visit Syrian Human Rights Committee web site on: http://www.shrc.org Postal Address: Syrian Human Rights Committee (SHRC) BCM Box: 2789, London WC1N 3XX, UK Fax: +44 (0)870 137 7678 Email: [email protected] 1 Report on the Human Rights Situation in Syria Over a 20-year Period FOREWORD The Syrian Human Rights Committee has issued its report on the human rights situation in Syria over a twenty-year period, at a time which coincides with rapid global changes and proper international developments, in favour of respecting democratic freedoms and safeguarding human rights. While the international trend is heading progressively towards promoting respect for human rights, the Syrian regime is moving against history and the spirit of the age, in a direction contrary to the Syrian, Arab, and international public opinion. Thus, the repressive nature of this regime represents the utmost setback to values and principles acknowledged by international legitimacy. This report, which is issued by the Syrian Human Rights Committee, deals with the human rights situation in Syria over a twenty-year period as of 1979, in which the Syrian people’s groups, parties, and sects moved and called for respecting human rights. -

The Silenced Kurds

October 1996 Vol. 8, No. 4(E) SYRIA THE SILENCED KURDS PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED REPORTS ON THE KURDISH MINORITY ............................................................................. 2 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 DENIAL OF A NATIONALITY............................................................................................................................................... 12 Background: Arabization Initiatives in Northeastern Syria ......................................................................................... 12 The 1962 Census and Its Consequences ...................................................................................................................... 13 The Kurdish “Foreigners”............................................................................................................................................ 16 The Kurdish Maktoumeen ........................................................................................................................................... 19 International