High Line Canal, Sand Creek Lateral HAER Blo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT Los Angeles, CA 90004 (323) 769-2520 • Fax: (323) 769-2521

UNITED STATES National Office 2814 Virginia St. Houston, Texas 77098 (713) 524-1264 • 1-800-594-5756 Fax: (713) 524-7165 2010 ANNUAL Western Region 662 N. Van Ness Ave. #203 REPORT Los Angeles, CA 90004 (323) 769-2520 • Fax: (323) 769-2521 Eastern Region Two Hartford Square West 146 Wyllys Street, Ste. 2-305 Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 904-5493 • Fax: (860) 904-5268 CANADA 1680 Lakeshore Road West, Ste. 5 Mississauga, ON L5J 1J5 (904) 403-8652 e-mail: [email protected] www.sunshinekids.org A Message from our Board Chairperson Dear Sunshine Kids Family, 2010 has been such a wonderful year for the Sunshine Kids Foundation! We are always grateful for the generosity of our donors and volunteers. Without your continued support, we could not have weathered the challenging economic times. The Sunshine Kids Foundation has been touching the lives of children with cancer since 1982. This past year, our family of dedicated staff and volunteers continued to do just that. They planned and implemented 10 national trips, hundreds of regional activities and in-hospital events. Our Kids participated in activities as varied as riding in a Mardi Gras Parade, visiting the set of the TV show “Vampire Diaries”, attending the NBA All-Star game, experiencing the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus and even meeting the Jonas Brothers. What a positive and exciting year it has been! Mission: The Sunshine Kids Foundation adds quality of It is truly an honor to serve as the newly elected Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Sunshine Kids Foundation. -

The Giffin Family Pioneers in America Prior to 17 42

The Giffin Family Pioneers in America Prior to 17 42 This Giffin History has to do with at least Eight Genera tions in America, widely scattered in many of the Far West States, as well as in the Eastern and Middle States. Following the Descent of Andrew Giffin I, from Eastern Penna. "Big Spring," Cumberland County And of his Son, the fourth born of his Five Children, Andrew Giffin II, to Western Penna. Washington County, in 1797 Scotch in Origin, Daring and Venturesome in Spirit, Fearless in their Every Undertaking. Published August 24, 1933 Giffin Reunion Association, Canonsburg, Pa. Wm. Ewing Giffin, Pres., R. D. 1, Bridgeville, Pa. S. Alice Freed, Secy., R. D. 1, Bridgeville, Pa. T. Andrew Riggle, Treas., Houston, Pa. Book arranged by William W. Rankin Manufactured in Pittsburgh, Penna., by American Printing Company The Giffin Family Dedicated to the Unnamed Gua,ontors who generously made the J,ublishing of this book possible by their payment in advance for a sufficient number of the books to justify the Publishing Committee in placing the order for the printing of the work.Starting at the Bienlfial Giffin Reunion August 20, 1915, with Twenty-six Dollars, this fund was at the 1931 Reunion and since, increased to several hundred dollars. Meanwhile for eighteen years, the original nest-egg has been gathering interest in a Sav ings Bank and is now being put to practical use. The Giffin Reunion Association. Contents Frontispiece, Dr. Isaac Boyce 4 Title Page 5 Dedicatio" 6 Are You a Giffin! Buy a Family History 8 Contents 9 Foreword 10 Portrait of Isaac Newton Boyce, Owr Eldest Giffin 12 History of the Giffin Family 13 Summary of Generations 33 Indexing Library System 34 William Giffin 49 Nancy Agnes Giffin 63 I ane Giffin 82 Joh,. -

Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 Dktentry: 4-1 Page: 1 of 44

Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 DktEntry: 4-1 Page: 1 of 44 No. 12-17046 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT Valle del Sol. et al., No. 12-17046 Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. No. 2:10-cv-01061-PHX-SRB District of Arizona Michael B. Whiting, et al., Defendants-Appellees, and State of Arizona and Janice K. Brewer, Intervenor Defendants- Appellees. EMERGENCY MOTION UNDER CIRCUIT RULE 27-3 FOR AN INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL Thomas A. Saenz Linton Joaquin Victor Viramontes Karen C. Tumlin Nicholás Espíritu Nora A. Preciado MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL Melissa S. Keaney DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND Alvaro M. Huerta 634 S. Spring Street, 11th Floor NATIONAL IMMIGRATION LAW Los Angeles, California 90014 CENTER Telephone: (213) 629-2512 3435 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 2850 Los Angeles, California 90010 Omar C. Jadwat Telephone: (213) 639-3900 Andre Segura AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION IMMIGRANTS’ RIGHTS PROJECT Attorneys for Appellants 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, New York 10004 Additional Counsel on the following Telephone: (212) 549-2660 pages Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 DktEntry: 4-1 Page: 2 of 44 Nina Perales Cecillia D. Wang MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND UNION FOUNDATION 110 Broadway Street, Suite 300 IMMIGRANTS’ RIGHTS PROJECT San Antonio, Texas 78205 39 Drum Street Telephone: (210) 224-5476 San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: (415) 343-0775 Chris Newman Daniel J. Pochoda Lisa Kung James Duff Lyall NATIONAL DAY LABOR ACLU FOUNDATION OF ORGANIZING NETWORK 675 S. Park ARIZONA View Street, Suite B Los Angeles, 3707 N. -

![[RR83550000, 201R5065C6, RX.59389832.1009676] Quarterly Status Repo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3880/rr83550000-201r5065c6-rx-59389832-1009676-quarterly-status-repo-863880.webp)

[RR83550000, 201R5065C6, RX.59389832.1009676] Quarterly Status Repo

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 03/31/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-06620, and on govinfo.gov 4332-90-P DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Reclamation [RR83550000, 201R5065C6, RX.59389832.1009676] Quarterly Status Report of Water Service, Repayment, and Other Water-Related Contract Actions AGENCY: Bureau of Reclamation, Interior. ACTION: Notice of contract actions. SUMMARY: Notice is hereby given of contractual actions that have been proposed to the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and are new, discontinued, or completed since the last publication of this notice. This notice is one of a variety of means used to inform the public about proposed contractual actions for capital recovery and management of project resources and facilities consistent with section 9(f) of the Reclamation Project Act of 1939. Additional announcements of individual contract actions may be published in the Federal Register and in newspapers of general circulation in the areas determined by Reclamation to be affected by the proposed action. ADDRESSES: The identity of the approving officer and other information pertaining to a specific contract proposal may be obtained by calling or writing the appropriate regional office at the address and telephone number given for each region in the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION section of this notice. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Michelle Kelly, Reclamation Law Administration Division, Bureau of Reclamation, P.O. Box 25007, Denver, Colorado 1 80225-0007; [email protected]; telephone 303-445-2888. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Consistent with section 9(f) of the Reclamation Project Act of 1939, and the rules and regulations published in 52 FR 11954, April 13, 1987 (43 CFR 426.22), Reclamation will publish notice of proposed or amendatory contract actions for any contract for the delivery of project water for authorized uses in newspapers of general circulation in the affected area at least 60 days prior to contract execution. -

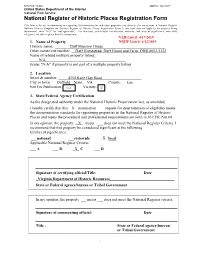

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 1. Name of Property NRHP Listed: 6/12/2019 Historic name: Duff Mansion House Other names/site number: Duff Homestead; Duff House and Farm; DHR #052-5122 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 4354 Kane Gap Road City or town: Duffield State: VA County: Lee Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

Survey of Biological Resources in the Triple Creek Greenway City of Aurora

Joint Project Funding Request For Triple Creek Greenway Corridor Phase 3: Implementation Arapahoe County Open Spaces September 8, 2015 JOINT PROJECT FUNDING REQUEST Triple Creek Greenway Corridor Phase 3: Acquisition 1) Scope of Project The Triple Creek Greenway Corridor (TCGC) is comprised of land acquisitions, trail expansions, and trailhead development projects designed to expand and extend the greenway. Building on the success of acquisitions completed under our previous joint project, this phase includes properties that will complete the greenway and trail along Murphy Creek and protect the headwaters of Sand Creek at the confluence of Coal Creek and Senac Creek. A majority of these properties will remain undeveloped and provide permanent protection along an area otherwise prime for future development. Please see map titled TCGW_Phase3_AreaMap for a view of all properties purchased in Phase 2 and planned acquisitions under this Joint funding project request. 2) Project Summary The Triple Creek Greenway Corridor project, comprised of Sand Creek, Coal Creek, and Senac Creek in southeast Aurora, is an ambitious plan to add fourteen miles of interconnected greenway and trails between the existing terminus of the Sand Creek Regional Greenway and nearly 30,000 contiguous acres of publicly owned land surrounding the Aurora Reservoir. When completed, pedestrians, bicyclists, equestrians, and wildlife will be able to travel an uninterrupted 27-mile route from the Aurora Reservoir to the South Platte River. In the larger context, the corridor will provide additional connective loops to the Front Range Trail segments including the High Line Canal, Cherry Creek Trail and Toll Gate Creek Trail for a wide variety of uses and public benefit. -

The Judicial Branch and the Efficient Administration of Justice

THE JUDICIAL BRANCH AND THE EFFICIENT ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COURTS, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, AND THE INTERNET OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 6, 2016 Serial No. 114–83 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 20–630 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia, Chairman F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan Wisconsin JERROLD NADLER, New York LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas ZOE LOFGREN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DARRELL E. ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., STEVE KING, Iowa Georgia TRENT FRANKS, Arizona PEDRO R. PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas JUDY CHU, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio TED DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah KAREN BASS, California TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana TREY GOWDY, South Carolina SUZAN DelBENE, Washington RAU´ L LABRADOR, Idaho HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island DOUG COLLINS, Georgia SCOTT PETERS, California RON DeSANTIS, Florida MIMI WALTERS, California KEN BUCK, Colorado JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas DAVE TROTT, Michigan MIKE BISHOP, Michigan SHELLEY HUSBAND, Chief of Staff & General Counsel PERRY APELBAUM, Minority Staff Director & Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON COURTS, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, AND THE INTERNET DARRELL E. -

![Elk City Mining News (Elk City, Idaho), 1908-05-16, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0017/elk-city-mining-news-elk-city-idaho-1908-05-16-p-2170017.webp)

Elk City Mining News (Elk City, Idaho), 1908-05-16, [P ]

- ’ LATE SPORTING EVENTS. The new Presbyterian church, built at a cost of $30,000. was dedicated at FLEETSABEATFRISCO To turn professional and that same NORTHWEST STATES Aberdeen Sunday. NEWS OF THE WORLS day to receive a terrific beating and i ■ be knocked out cold in the fourth OREGON ITEMS. round was the fate of Eddie Johnston, Mrs. Cynthia J. Shanks died recent FORTY-SIX BATTLERS FORMED WASHINGTON, IDAHO, OREGON SHORT DISPATCHES FROM ALL the well known Spokane boxer. John ly at Arlington, aged 65 years. ston was given the sleep producer at Henry P. Morrison, brakeman on the LINE IN THE BAY. Xewport Saturday night and it was ad AND MONTANA ITEMS. Heppner branch of the Oregon Rail FARTS OF THE GLOBE. r ministered by Louie Long's trusty road & Navigation company, shot and right. • , All Vessels of Pacific Fleet Joined A Few Interesting Items Gathered killed his sweetheart, Nora Wright, A Review of Happenings in BotEr f “ At Chicago George Sutton of Chi near Morgan and wounded Bonnie b Those of Atlantic and Made Grand cago defeated Willie Hoppe, 500 to 363, From Our Exchanges of the Sur Ahalt. her companion, at Heppner Eastern and Western Hemisphere» in the first block of 1500 points at 18.2 est Review Ever Held in History of rounding Country—Numerous Acci Sunday. During the Past Week-National, billiards. \ Nation—Every Kind of Fighting An unknown steamer or schooner, Whitman won the triangular track dents and Personal Events Take Historical, Political and Personal» lumber-laden and waterlogged, struck I Craft in Procession. meet at Tollman, getting 52 points to Place—Crop Outlook Good. -

Water Leasing in the Lower Arkansas Valley

DEVELOPMENT OF LAND FALLOWING- WATER LEASING IN THE LOWER ARKANSAS VALLEY (2002 through mid-2011) Sugar City (2011) JUNE 30, 2011 La Junta (2011) REPORT FOR THE COLORADO WATER CONSERVATION BOARD Formerly irrigated land below Colorado Canal (2011) Peter D. Nichols 1120 Lincoln Street • Suite 1600 Denver, Colorado 80203-2141 303-861-1963 [email protected] Currently irrigated land on the Ft. Lyon Canal ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people contributed to the formation of the Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy District, and subsequent incorporation of the Lower Arkansas Valley Super Ditch Company, Inc. These included Leroy Mauch (Prowers County Commissioner), Lynden Gill (Bent County Commissioner), John Singletary, Loretta Kennedy (Pueblo County Commissioner), Ollie Ridley, Bill Long (Bent County Commissioner), Bob Bauserman, Kevin Karney and Jake Klein (Otero County Commissioners), John Rose, and H. Barton Mendenhall, as well as current and former board members and staff of the District Pete Moore (current Chair), Melissa Esquibel (Secretary), Wayne Whittaker (Treasurer), Anthony Nunez (Director), Reeves Brown (Director), and Jay Winner (General Manager) and current and former Board members of the Company, John Schweizer (President), Dale Mauch (Vice‐ President), Burt Heckman (Secretary), Frank Melinski (Treasurer), Mike Barolo, Donny Hansen, Joel Lundquist, Lee Schweizer and Ray Smith. Many also contributed to the preparation of this report. Veronique Van Gheem, Esq., initially drafted Parts 2, 3 and 4 while a law student at CU, and graciously assisted in revisions after graduation. Anthony van Westrum, Esq., Anthony van Westrum, LLC; Denis Clanahan, Esq., Clanahan, Beck & Bean; and, Tom McMahon, Esq., Jones & Keller drafted the sections on the corporate organization, taxation, and antitrust issues respectively. -

Hydropower Generation Summary

Bureau of Reclamation - Hydropower Generation Summary Fiscal Year 2019, Q2 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation April 2019 Bureau of Reclamation - Hydropower Generation Summary (FY 2019 Q2) Summary The Bureau of Reclamation’s hydropower program supports Administration and Department of the Interior domestic energy security initiatives – facilitating the development of untapped hydropower potential on federal water resource projects through a number of activities, including collaborative regulatory reform; operational and technological innovation; and stakeholder outreach. Collectively, these activities derive additional value and revenue from existing public infrastructure. This summary report identifies federal and non-federal hydropower facilities and associated generating capacity currently online or in development on Reclamation projects – and reports on incremental hydropower capability installed within the quarter, as applicable. Incremental Hydropower Capability The Department of the Interior has identified incremental hydropower capability as a key performance indicator in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2018-2022 Strategic Plan.1 Incremental capability performance is reported in megawatts (MW) – consisting of MW derived from generator uprates and non-federal development; 2 and MW equivalents derived from turbine replacements and optimization installations, calculated by multiplying the resulting efficiency improvement by the MW capacity of the affected unit(s). No projects resulting in incremental capability were completed in FY 2019 Q2. 1 Available at: https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2018-2022-strategic-plan.pdf. 2 Non-federal hydropower developed on Reclamation projects in accordance with a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) License or Reclamation Lease of Power Privilege (LOPP). For additional information see: https://www.usbr.gov/power/LOPP. -

The University of Tulsa Magazine Is Published Three Times a Year Major National Scholarships

the university of TULSmagazinea 2001 spring NIT Champions! TU’s future is in the bag. Rediscover the joys of pudding cups, juice boxes, and sandwiches . and help TU in the process. In these times of tight budgets, it can be a challenge to find ways to support worthy causes. But here’s an idea: Why not brown bag it,and pass some of the savings on to TU? I Eating out can be an unexpected drain on your finances. By packing your lunch, you can save easy dollars, save commuting time and trouble, and maybe even eat healthier, too. (And, if you still have that childhood lunch pail, you can be amazingly cool again.) I Plus, when you share your savings with TU, you make a tremendous difference.Gifts to our Annual Fund support a wide variety of needs, from purchase of new equipment to maintenance of facilities. All of these are vital to our mission. I So please consider “brown bagging it for TU.” It could be the yummiest way everto support the University. I Watch the mail for more information. For more information on the TU Annual Fund, call (918) 631-2561, or mail your contribution to The University of Tulsa Annual Fund, 600 South College Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74104-3189. Or visit our secure donor page on the TU website: www.utulsa.edu/development/giving/. the university of TULSmagazinea features departments 16 A Poet’s Perspective 2 Editor’s Note 2001 By Deanna J. Harris 3 Campus Updates spring American poet and philosopher Robert Bly is one of the giants of 20th century literature. -

New Officer Seminar 2011 Washington, DC 20006 Office: (510) 724-9277 Phone: (202) 383-4820 Fax: (510) 724-1345 Fax: (202) 347-2319 14 Iron Workers on the Job EDWARD C

FEBRUARY 2011 NEW2011 OFFICER SEMINAR 62700_IW.indd 1 2/7/11 6:15 PM President’s Prepared and Ready to Lead Page Our Great Union pon the announcement by General Presi- an ironworker was ten years. Our union suf- Udent Joseph Hunt of his retirement at the fered a loss of one percent of our membership October 18, 2010 meeting of the general execu- per year as a result of jobsite fatalities. To- tive council, I was unanimously elected by the day, that would equate to nearly a thousand council to fulfill his unexpired term beginning ironworkers a year. We have made great prog- February 1, 2011, as the twelfth general presi- ress from those days, but as was made only dent of our great union. too clear as I attended the funeral of Brother I join with all of our members in our ap- Rock Mayles, Local 16 (Baltimore, Md.) on preciation and gratitude for General Presi- Christmas Eve, even one is too many. We dent Hunt’s remarkable tenure as our general must view every accident as a failure of our president where his dedication and leadership collective efforts—union, member and con- steered our union through perilous times and tractor to work safely and fight for life. The enhanced our reputation within the construc- battle on safety cannot be lost, and will not be tion industry. My thanks to him, not only for lost. We will dedicate ourselves to eliminating his accomplishments, but also for the confi- this tragedy. dence, support, and friendship he has shown The strength and future of our union lies in me over the years.