The Judicial Branch and the Efficient Administration of Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Consider Possible Impeachment of United States District Judge G

TO CONSIDER POSSIBLE IMPEACHMENT OF UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE G. THOMAS PORTEOUS, JR. (PART I) HEARING BEFORE THE TASK FORCE ON JUDICIAL IMPEACHMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 17 AND 18, 2009 Serial No. 111–43 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–638 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 10:13 Feb 02, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\JUDIMP\11171809\53638.000 HJUD1 PsN: DOUGA COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California MAXINE WATERS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE KING, Iowa STEVE COHEN, Tennessee TRENT FRANKS, Arizona HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas Georgia JIM JORDAN, Ohio PEDRO PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico TED POE, Texas MIKE QUIGLEY, Illinois JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah JUDY CHU, California TOM ROONEY, Florida LUIS V. -

REPORT Los Angeles, CA 90004 (323) 769-2520 • Fax: (323) 769-2521

UNITED STATES National Office 2814 Virginia St. Houston, Texas 77098 (713) 524-1264 • 1-800-594-5756 Fax: (713) 524-7165 2010 ANNUAL Western Region 662 N. Van Ness Ave. #203 REPORT Los Angeles, CA 90004 (323) 769-2520 • Fax: (323) 769-2521 Eastern Region Two Hartford Square West 146 Wyllys Street, Ste. 2-305 Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 904-5493 • Fax: (860) 904-5268 CANADA 1680 Lakeshore Road West, Ste. 5 Mississauga, ON L5J 1J5 (904) 403-8652 e-mail: [email protected] www.sunshinekids.org A Message from our Board Chairperson Dear Sunshine Kids Family, 2010 has been such a wonderful year for the Sunshine Kids Foundation! We are always grateful for the generosity of our donors and volunteers. Without your continued support, we could not have weathered the challenging economic times. The Sunshine Kids Foundation has been touching the lives of children with cancer since 1982. This past year, our family of dedicated staff and volunteers continued to do just that. They planned and implemented 10 national trips, hundreds of regional activities and in-hospital events. Our Kids participated in activities as varied as riding in a Mardi Gras Parade, visiting the set of the TV show “Vampire Diaries”, attending the NBA All-Star game, experiencing the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus and even meeting the Jonas Brothers. What a positive and exciting year it has been! Mission: The Sunshine Kids Foundation adds quality of It is truly an honor to serve as the newly elected Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Sunshine Kids Foundation. -

The Giffin Family Pioneers in America Prior to 17 42

The Giffin Family Pioneers in America Prior to 17 42 This Giffin History has to do with at least Eight Genera tions in America, widely scattered in many of the Far West States, as well as in the Eastern and Middle States. Following the Descent of Andrew Giffin I, from Eastern Penna. "Big Spring," Cumberland County And of his Son, the fourth born of his Five Children, Andrew Giffin II, to Western Penna. Washington County, in 1797 Scotch in Origin, Daring and Venturesome in Spirit, Fearless in their Every Undertaking. Published August 24, 1933 Giffin Reunion Association, Canonsburg, Pa. Wm. Ewing Giffin, Pres., R. D. 1, Bridgeville, Pa. S. Alice Freed, Secy., R. D. 1, Bridgeville, Pa. T. Andrew Riggle, Treas., Houston, Pa. Book arranged by William W. Rankin Manufactured in Pittsburgh, Penna., by American Printing Company The Giffin Family Dedicated to the Unnamed Gua,ontors who generously made the J,ublishing of this book possible by their payment in advance for a sufficient number of the books to justify the Publishing Committee in placing the order for the printing of the work.Starting at the Bienlfial Giffin Reunion August 20, 1915, with Twenty-six Dollars, this fund was at the 1931 Reunion and since, increased to several hundred dollars. Meanwhile for eighteen years, the original nest-egg has been gathering interest in a Sav ings Bank and is now being put to practical use. The Giffin Reunion Association. Contents Frontispiece, Dr. Isaac Boyce 4 Title Page 5 Dedicatio" 6 Are You a Giffin! Buy a Family History 8 Contents 9 Foreword 10 Portrait of Isaac Newton Boyce, Owr Eldest Giffin 12 History of the Giffin Family 13 Summary of Generations 33 Indexing Library System 34 William Giffin 49 Nancy Agnes Giffin 63 I ane Giffin 82 Joh,. -

Executive Accountability Act of 2009

EXECUTIVE ACCOUNTABILITY ACT OF 2009 HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIME, TERRORISM, AND HOMELAND SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 743 JULY 27, 2009 Serial No. 111–72 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 51–345 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 13:52 Apr 27, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CRIME\072709\51345.000 HJUD1 PsN: 51345 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California MAXINE WATERS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE KING, Iowa STEVE COHEN, Tennessee TRENT FRANKS, Arizona HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas Georgia JIM JORDAN, Ohio PEDRO PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico TED POE, Texas MIKE QUIGLEY, Illinois JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM ROONEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California GREGG HARPER, Mississippi TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin CHARLES A. -

Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 Dktentry: 4-1 Page: 1 of 44

Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 DktEntry: 4-1 Page: 1 of 44 No. 12-17046 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT Valle del Sol. et al., No. 12-17046 Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. No. 2:10-cv-01061-PHX-SRB District of Arizona Michael B. Whiting, et al., Defendants-Appellees, and State of Arizona and Janice K. Brewer, Intervenor Defendants- Appellees. EMERGENCY MOTION UNDER CIRCUIT RULE 27-3 FOR AN INJUNCTION PENDING APPEAL Thomas A. Saenz Linton Joaquin Victor Viramontes Karen C. Tumlin Nicholás Espíritu Nora A. Preciado MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL Melissa S. Keaney DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND Alvaro M. Huerta 634 S. Spring Street, 11th Floor NATIONAL IMMIGRATION LAW Los Angeles, California 90014 CENTER Telephone: (213) 629-2512 3435 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 2850 Los Angeles, California 90010 Omar C. Jadwat Telephone: (213) 639-3900 Andre Segura AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION IMMIGRANTS’ RIGHTS PROJECT Attorneys for Appellants 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, New York 10004 Additional Counsel on the following Telephone: (212) 549-2660 pages Case: 12-17046 09/14/2012 ID: 8324887 DktEntry: 4-1 Page: 2 of 44 Nina Perales Cecillia D. Wang MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND UNION FOUNDATION 110 Broadway Street, Suite 300 IMMIGRANTS’ RIGHTS PROJECT San Antonio, Texas 78205 39 Drum Street Telephone: (210) 224-5476 San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: (415) 343-0775 Chris Newman Daniel J. Pochoda Lisa Kung James Duff Lyall NATIONAL DAY LABOR ACLU FOUNDATION OF ORGANIZING NETWORK 675 S. Park ARIZONA View Street, Suite B Los Angeles, 3707 N. -

Executive Overreach in Domestic Affairs (Part Ii)—Irs Abuse, Welfare Reform, and Other Issues

EXECUTIVE OVERREACH IN DOMESTIC AFFAIRS (PART II)—IRS ABUSE, WELFARE REFORM, AND OTHER ISSUES HEARING BEFORE THE EXECUTIVE OVERREACH TASK FORCE OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 19, 2016 Serial No. 114–71 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 99–839 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia, Chairman F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan Wisconsin JERROLD NADLER, New York LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas ZOE LOFGREN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DARRELL E. ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., STEVE KING, Iowa Georgia TRENT FRANKS, Arizona PEDRO R. PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas JUDY CHU, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio TED DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah KAREN BASS, California TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana TREY GOWDY, South Carolina SUZAN DelBENE, Washington RAU´ L LABRADOR, Idaho HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island DOUG COLLINS, Georgia SCOTT PETERS, California RON DeSANTIS, Florida MIMI WALTERS, California KEN BUCK, Colorado JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas DAVE TROTT, Michigan MIKE BISHOP, Michigan SHELLEY HUSBAND, Chief of Staff & General Counsel PERRY APELBAUM, Minority Staff Director & Chief Counsel EXECUTIVE OVERREACH TASK FORCE STEVE KING, Iowa, Chairman F. -

Swinney’S Success MILTON A

U.S. named Pro-life evangelicals to gather on latest in nation’s capital persecution report Page 4 Page 7 JANUARY 28, 2017 • News Journal of North Carolina Baptists • VOLUME 183 NO. 2 • BRnow.org National SBC High court URGED meetings take shape to reverse BR staff lans are well underway for the two largest annual gatherings pro-transgender ruling of Southern Baptists in 2017 – Pthe annual meeting and the pastors’ conference – both of which By TOM STRODE | Baptist Press will take place in Phoenix, Ariz., in he Southern Baptist Ethics & Virginia county violated federal law “The administration has attempted early summer. Religious Liberty Commission by refusing to permit a transgender to create new law through the execu- The annual meeting of the (ERLC) has joined with other high school student – who is a female tive branch that jeopardizes student Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) Tfaith organizations to urge the biologically but identifies as a male privacy, undermines parental authority is scheduled for June 13-14. Presi- U.S. Supreme Court to overturn a – to use the boys’ restroom. In a 2-1 and further conflicts with religious dent Steve Gaines announced the lower-court ruling that a federal anti- opinion overturning a federal judge, liberty,” Wussow told Baptist Press in event’s theme in mid-December: discrimination law regarding sex cov- the Fourth Circuit panel agreed with written comments. “If any president “Pray! For such a time as this,” taken ers gender identity. an Obama administration letter in wishes to redefine what the words from Esther 4:14 and Luke 11:1. -

Sunshine in the Courtroom Act of 2007

SUNSHINE IN THE COURTROOM ACT OF 2007 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2128 SEPTEMBER 27, 2007 Serial No. 110–160 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 37–979 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:09 Mar 11, 2009 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\FULL\092707\37979.000 HJUD1 PsN: 37979 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. WEINER, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ADAM B. -

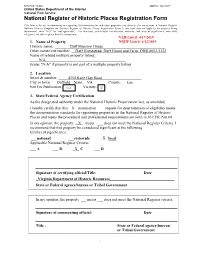

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 1. Name of Property NRHP Listed: 6/12/2019 Historic name: Duff Mansion House Other names/site number: Duff Homestead; Duff House and Farm; DHR #052-5122 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 4354 Kane Gap Road City or town: Duffield State: VA County: Lee Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2012

VERIZON POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS JANUARY – DECEMBER 2012 1 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2012 A Message from Craig Silliman Verizon is affected by a wide variety of government policies ‐‐ from telecommunications regulation to taxation to health care and more ‐‐ that have an enormous impact on the business climate in which we operate. We owe it to our shareowners, employees and customers to advocate public policies that will enable us to compete fairly and freely in the marketplace. Political contributions are one way we support the democratic electoral process and participate in the policy dialogue. Our employees have established political action committees at the federal level and in 20 states. These political action committees (PACs) allow employees to pool their resources to support candidates for office who generally support the public policies our employees advocate. This report lists all PAC contributions, corporate political contributions, support for ballot initiatives and independent expenditures made by Verizon in 2012. The contribution process is overseen by the Corporate Governance and Policy Committee of our Board of Directors, which receives a comprehensive report and briefing on these activities at least annually. We intend to update this voluntary disclosure twice a year and publish it on our corporate website. We believe this transparency with respect to our political spending is in keeping with our commitment to good corporate governance and a further sign of our responsiveness to the interests of our shareowners. Craig L. Silliman Senior Vice President, Public Policy 2 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2012 Political Contributions Policy: Our Voice in the Political Process What are the Verizon Good Government Clubs? and the government agencies administering the federal and individual state election laws. -

VA Leadership Prayer List 2010 Leaders-Monthly Spiritual 1

VA Leadership Prayer List Senators (by District) contd. Delegates (by District) contd.Delegates (by District) contd. 24 Emmett W. Hanger, Jr. 33 Joe T. May 89 Kenneth C. Alexander 2010 Leaders-Monthly th 25 R. Creigh Deeds 9 34 Barbara J. Comstock 90 Algie T. Howell, Jr. Spiritual th 26 Mark D. Obenshain 35 Mark L. Keam 17 91 Thomas D. Gear st th Your Pastor(s) __ 1 27 Jill Holtzman Vogel 36 Kenneth R. Plum 92 Jeion A. Ward 25 Executive 28 Richard H. Stuart 37 David Bulova 93 Robin A. Abbott President Obama 29 Charles J. Colgan 38 L. Kaye Kory 94 G. Glenn Oder th Vice President Biden 30 Patricia S. Ticer 10 39 Vivian E. Watts 95 Mamye E. BaCote State Leadership 31 Mary Margaret Whipple, 40 Timothy D. Hugo 96 Brenda Pogge Governor – Bob McDonnell Dem. Caucus Chair 41 Eileen Filler-Corn 97 Chris Peace th Lieutenant Governor – Bill Bolling 32 Janet D. Howell 42 David B. Albo 18 98 Harvey B. Morgan President of the State Senate 33 Mark R. Herring 43 Mark D. Sickles 99 Albert C. Pollard nd Attorney General–Ken Cuccinelli 2 34 Chap Petersen 44 Scott A. Surovell 100 Lynwood W. Lewis, Jr. 26 35 Richard L. Saslaw, 45 David Englin Judicial Legislative th Congress – VA Representatives Majority Leader 11 46 Charniele Herring US Supreme Court Justices Senator Mark Warner 36 Linda T. Puller 47 Patrick A. Hope Chief Justice John Roberts 37 David W. Marsden 48 Robert H. Brink Senator Jim Webb th Justice John Paul Stevens 1 Representative Robert Wittman 38 Phillip P.