Plant Based “Milk” Labeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Healthful Soybean

FN-SSB.104 THE HEALTHFUL SOYBEAN Soy protein bars, soy milk, soy cookies, soy burgers .…. the list of soy products goes on. Soybeans are best known as a source of high quality protein. They are also rich in calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin E, several B-vitamins, and fiber. But in 1999, soy took the nation by storm. The Food and Drug Administration approved health claims that soy protein may lower the risk of heart disease if at least 25 grams of soy protein are consumed daily. This benefit may be because soybeans are low saturated fat, have an abundance of omega-3 fatty acids, and are rich in isoflavones. Research continues to explore health benefits linked to the healthful soybean. Beyond research, edamame, tempeh, tofu, and soy milk make the base for some truly delectable dishes. Exploring Soyfoods Fresh Green Soybeans Edamame (fresh green soybeans) have a sweet, buttery flavor and a tender-firm texture. Fresh soybeans still in the pod should be cooked and stored in the refrigerator. Handle frozen soybeans as you would any other frozen vegetable. The easiest way to cook washed, fresh soybeans in the pod is to simmer them in salted water for 5 minutes. Once the beans are drained and cooled, remove them from the pod. Eat as a snack or simmer an additional 10 to 15 minutes to use as a side dish. Substitute soybeans for lima beans, mix the beans into soups or casseroles in place of cooked dried beans, or toss the beans with pasta or rice salads. Dried Soybeans Dried mature soybeans are cooked like other dried beans. -

Plant-Based Milk Alternatives

Behind the hype: Plant-based milk alternatives Why is this an issue? Health concerns, sustainability and changing diets are some of the reasons people are choosing plant-based alternatives to cow’s milk. This rise in popularity has led to an increased range of milk alternatives becoming available. Generally, these alternatives contain less nutrients than cow’s milk. In particular, cow’s milk is an important source of calcium, which is essential for growth and development of strong bones and teeth. The nutritional content of plant-based milks is an important consideration when replacing cow’s milk in the diet, especially for young children under two-years-old, who have high nutrition needs. What are plant-based Table 1: Some Nutrients in milk alternatives? cow’s milk and plant-based Plant-based milk alternatives include legume milk alternatives (soy milk), nut (almond, cashew, coconut, macadamia) and cereal-based (rice, oat). Other ingredients can include vegetable oils, sugar, and thickening ingredients Milk type Energy Protein Calcium kJ/100ml g/100ml mg/100ml such as gums, emulsifiers and flavouring. Homogenised cow’s milk 263 3.3 120 How are plant-based milk Legume alternatives nutritionally Soy milk 235-270 3.0-3.5 120-160* different to cow’s milk? Nut Almond milk 65-160 0.4-0.7 75-120* Plant-based milk alternatives contain less protein and Cashew milk 70 0.4 120* energy. Unfortified versions also contain very little calcium, B vitamins (including B12) and vitamin D Coconut milk** 95-100 0.2 75-120* compared to cow’s milk. -

Final-DDC-PDF.Pdf

@switch4good Hello, and welcome to the Ditch Dairy Challenge! Whether you’re all-in or a bit skeptical, we want you to have the best experience possible, and we’re here to help. This isn’t your typical challenge—you won’t feel like you’re grinding it out to feel better once it’s complete. You’re going to feel awesome both during and after the 10 days—it’s incredible what ditching dairy can do for our bodies. Use this guide curated by our Switch4Good experts for quick tips and information to make the most of this challenge. From nutrition to recipes, OUR experts have got you covered! Don’t forget to document your journey on Instagram and tag #DitchDairyChallenge. Protein facts How Much Protein Do I Need? Recommended Daily Amount = 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight (or 0.4 grams per pound) FUN FACTS If you’re eating a 2,000-calories-a-day diet and only ate broccoli, you’d get 146 grams of protein per day! Even a full day’s worth of plain mashed potatoes would give you 42 grams of protein per day. TOO MUCH Too much protein can stress the liver and kidneys. PROTEIN It can also cause stomach issues, bad breath, and weight gain. Proteins are made of 22 amino acids or “building blocks.” Our bodies can produce 13 of these, and 9 we synthesize from food (like plants). What Are Complete Proteins? Complete proteins contain all 9 essential amino acids that our body cannot make. Thankfully, If you eat enough calories and a variety of plant-based foods, you don’t have to worry! But, if you’re curious: tofu, tempeh, edamame, soy milk, quinoa, hemp seeds, and chia seeds (which is really just the beginning!). -

Soy Free Diet Avoiding Soy

SOY FREE DIET AVOIDING SOY An allergy to soy is common in babies and young children, studies show that often children outgrow a soy allergy by age 3 years and the majority by age 10. Soybeans are a member of the legume family; examples of other legumes include beans, peas, lentils and peanut. It is important to remember that children with a soy allergy are not necessarily allergic to other legumes, request more clarification from your allergist if you are concerned. Children with a soy allergy may have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, difficulty breathing, and or a skin reaction after eating or drinking soy products. These symptoms can be avoided by following a soy free diet. What foods are not allowed on a soy free diet? Soy beans and edamame Soy products, including tofu, miso, natto, soy sauce (including sho yu, tamari), soy milk/creamer/ice cream/yogurt, soy nuts and soy protein, tempeh, textured vegetable protein (TVP) Caution with processed foods - soy is widely used manufactured food products – remember to carefully read labels. o Soy products and derivatives can be found in many foods, including baked goods, canned tuna and meat, cereals, cookies, crackers, high-protein energy bars, drinks and snacks, infant formulas, low- fat peanut butter, processed meats, sauces, chips, canned broths and soups, condiments and salad dressings (Bragg’s Liquid Aminos) USE EXTRA CAUTION WITH ASIAN CUISINE: Asian cuisine are considered high-risk for people with soy allergy due to the common use of soy as an ingredient and the possibility of cross-contamination, even if a soy-free item is ordered. -

Allergen and Special Diet

ALLERGEN AND SPECIAL DIET PEANUTS TREE NUTS SOY MILK EGG WHEAT KOSHER GLUTEN VEGAN EXCLUDES COCONUT FREE BASES DAIRY Organic Signature Premium NON-DAIRY Cashew Coconut Mango Sorbet Nitrodole™ (Pineapple Sorbet) Piña Colada Sorbet Strawberry Sorbet FLAVORS Banana Birthday Cake Cap’n Crunch® Cheesecake Chocolate Cookie Butter Cookie Monster Cookies & Cream (Oreo®) Frosted Animal Cookie Fruity Pebbles® Madagascar Vanilla Bean Matcha Green Tea Milk Coffee Mint Nutella® Reese’s Peanut Butter® Ruby Cacao (Signature Premium Base Only) Sea Salt Caramel Strawberry Thai Tea TOPPINGS CANDIES Heath® Mini Chocolate Chips Mini Gummy Bears Mini Marshmallows Mochi Rainbow Sprinkles Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups® Unicorn Dust CEREALS, COOKIES & CAKES Biscoff® Cookies Brownie Bites Cap’n Crunch® Cheesecake Bites Chips Ahoy® Cookies Cookie Dough Bites Frosted Animal Cookies Fruity Pebbles® Graham Crackers Melba Toast Oreo® Cookies *Products may contain traces of allergens (peanuts, tree nuts, soy, milk, eggs or wheat) or other food sensitivities from a manufacturing facility or cross contact DISCLAIMER Your health is of the utmost importance and we strive to minimize the potential risk of cross contact by maintaining high standards of food safety practices. Vegan, non-dairy, and customers with other health and/or diet restrictions should review this document and the special diet and ingredient information available on our website. Due to menu constant menu changes, please be aware the information provided may not 100% reflect products served in store. Last updated 062019 If you have further questions regarding the nutritional information, please contact us at [email protected]. *Percent daily Values (DV) are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. -

Plant-Based Milk Guide Overview and Recommendations a Generation Ago, If You Avoided Milk You Didn’T Have Many Options

Plant-Based Milk Guide Overview and Recommendations A generation ago, if you avoided milk you didn’t have many options. Perhaps you could find soymilk in a health food store if you were lucky. Today, things have changed dramatically. You can find milk-like beverages made from all sorts of plants, including nuts, seeds, and grains. In general, many plant-based milks are good alternatives to cow’s milk. Some are higher in fat, saturated fat, sugar, or sodium, however, while others can’t compare to the amount of protein, vitamins, and minerals. Keep these tips in mind to meet your nutrient needs while choosing plant-based milks: • Protein. Choose plant-based milks containing at least 5 g of protein per cup to help you meet your daily protein needs. If your favorite type is low in protein, choose other protein-rich foods throughout the day, such as nuts, nut butters, beans, lentils and tofu to fill in the gaps. • Bone Nutrients. Calcium and vitamin D are important for bone health. Fortunately, many plant-based milks are fortified with both. If, however, your drink of choice doesn’t provide these nutrients, choose other calcium- and vitamin D-rich foods throughout the day, such as kale, spinach, and calcium- and vitamin D-fortified juices and cereals. • Saturated Fat. You may notice coconut milk is higher in saturated fat than other plant milks. Like other foods high in this form of unhealthy fat, if you like it, simply enjoy it in moderation. Plant-Based Milks Nutritional Comparison Plant-based Milks Sat Fat Carbs Sodium Sugar Protein Calcium -

Growing Trend of Veganism in Metropolitan Cities: Emphasis on Baking

GROWING TREND OF VEGANISM IN METROPOLITAN CITIES: EMPHASIS ON BAKING 1 2 *Kritika Bose Guha and Prakhar Gupta 1Assistant Lecturer, Institute of Hotel Management, Kolkata , 2Student, Institute of Hotel Management Catering Technology and Applied Nutrition, Pusa, New Delhi [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Veganism is a new food trend is gaining momentum in India. A diet based on large quantities of fruit and vegetables has a positive impact on our health. A vegan diet is based on plants and has increased in popularity over the recent years. Health is the most central reason for choosing a vegan diet. Meat free diets in India can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization, and Indian culture shows a great respect for animals in various cultural texts. Every major Indian religion viz. Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism encourage ahinsa that is non-violence toward other living beings. In modern India bakery products have made a way into our homes. Cakes, Breads, Puddings, Pie etc. are a common thing which can be now found in every household list. The challenge is each of these products contain animal based product and people who are following veganism cannot consume them. Vegan baking is a challenge because of the use of various products like eggs, milk, etc. in normal recipes. Several Chefs and companies are working on products that are vegan. Everyday more substitutes are coming and Market is growing with a steady pace. Objective: To study and find out the trend of vegan baking in Metropolitan Cities of India and spread awareness about Vegan Baking. Methodology: The study was conducted by a random sampling survey from cities Kolkata and Delhi, taking the opinions of consumers through a self-designed questionnaire who have opted for Veganism, & their needs. -

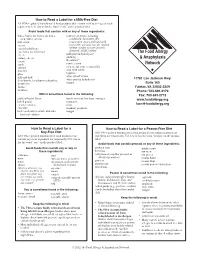

How to Read a Label for a Milk-Free Diet All FDA-Regulated Manufactured Food Products That Contain Milk As an Ingredient Are Required by U.S

How to Read a Label for a Milk-Free Diet All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that contain milk as an ingredient are required by U.S. law to list the word “milk” on the product label. Avoid foods that contain milk or any of these ingredients: butter, butter fat, butter oil, butter milk (in all forms, including acid, butter ester(s) condensed, derivative, dry, buttermilk evaporated, goat’s milk and milk casein from other animals, low fat, malted, casein hydrolysate milkfat, nonfat, powder, protein, caseinates (in all forms) skimmed, solids, whole) cheese milk protein hydrolysate pudding cottage cheese ® cream Recaldent curds rennet casein custard sour cream, sour cream solids diacetyl sour milk solids ghee tagatose whey (in all forms) half-and-half 11781 Lee Jackson Hwy. lactalbumin, lactalbumin phosphate whey protein hydrolysate lactoferrin yogurt Suite 160 lactose Fairfax, VA 22033-3309 lactulose Phone: 703-691-3179 Milk is sometimes found in the following: Fax: 703-691-2713 artificial butter flavor luncheon meat, hot dogs, sausages www.foodallergy.org baked goods margarine caramel candies nisin [email protected] chocolate nondairy products lactic acid starter culture and other nougat bacterial cultures How to Read a Label for a How to Read a Label for a Peanut-Free Diet Soy-Free Diet All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that contain peanut as an All FDA-regulated manufactured food products that ingredient are required by U.S. law to list the word “peanut” on the product contain soy as an ingredient are required by U.S. law to label. list the word “soy” on the product label. -

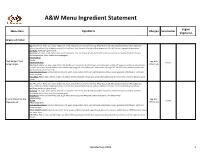

Menu Ingredient Statement

A&W Menu Ingredient Statement Vegan/ Menu Item Ingredients Allergen Sensitivities Vegetarian Burgers and Chicken Bun: Wheat Flour, Water, Corn Syrup, Soybean Oil, Yeast, Contains 2% or less of the following: Wheat Gluten, Salt, Malt, Dough Conditioners (Monoglycerides, Sodium Stearoyl Lactylate, Azodicarbonamide), Artificial Flavor, Yeast Nutrients (Calcium Sulfate, Ammonium Chloride), Calcium Propionate (Preservative). Beef Patty: Hamburger (ground beef). Seasoning: Salt, sugar, spices, paprika, dextrose, onion powder, corn starch, garlic powder, hydrolyzed cornprotein, extractive of paprika, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, silicon dioxide (anti-caking agent). Iceberg Lettuce Tomato Papa Burger/ Papa Egg, Milk, Yellow Onion Slices Gluten Burger Single Papa Sauce: Soybean oil, water, sugar, pickle relish (pickles, corn sweeteners, distilled vinegar, salt, xanthan gum, alum 0.10% potassium sorbate as a preservative, Wheat, Soy turmeric, natural spice flavors), tomato paste, distilled vinegar, egg yolk, salt, xanthan gum, artificial color including FD&C Red #40, spices, oleoresin paprika, Beta Apo-8-Carotenal, natural flavorings. Sharp American Cheese: Cultured milk and skim milk, water, cream, sodium citrate, salt, sorbic acid (preservative), sodium phosphate, artificial color, acetic acid, lecithin, enzymes. Pickle Slices: Pickles, water, distilled vinegar, salt, calcium chloride, potassium sorbate (as a preservative), polysorbate 80, natural flavors, turmeric oleoresin, garlic powder. Bun: Wheat Flour, Water, Corn Syrup, Soybean Oil, Yeast, Contains 2% or less of the following: Wheat Gluten, Salt, Malt, Dough Conditioners (Monoglycerides, Sodium Stearoyl Lactylate, Azodicarbonamide), Artificial Flavor, Yeast Nutrients (Calcium Sulfate, Ammonium Chloride), Calcium Propionate (Preservative). Beef Patty: Hamburger (ground beef). Seasoning: Salt, sugar, spices, paprika, dextrose, onion powder, corn starch, garlic powder, hydrolyzed cornprotein, extractive of paprika, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, silicon dioxide (anti-caking agent). -

Vegetarian Starter Kit You from a Family Every Time Hold in Your Hands Today

inside: Vegetarian recipes tips Starter info Kit everything you need to know to adopt a healthy and compassionate diet the of how story i became vegetarian Chinese, Indian, Thai, and Middle Eastern dishes were vegetarian. I now know that being a vegetarian is as simple as choosing your dinner from a different section of the menu and shopping in a different aisle of the MFA’s Executive Director Nathan Runkle. grocery store. Though the animals were my initial reason for Dear Friend, eliminating meat, dairy and eggs from my diet, the health benefi ts of my I became a vegetarian when I was 11 years old, after choice were soon picking up and taking to heart the content of a piece apparent. Coming of literature very similar to this Vegetarian Starter Kit you from a family every time hold in your hands today. plagued with cancer we eat we Growing up on a small farm off the back country and heart disease, roads of Saint Paris, Ohio, I was surrounded by which drastically cut are making animals since the day I was born. Like most children, short the lives of I grew up with a natural affi nity for animals, and over both my mother and time I developed strong bonds and friendships with grandfather, I was a powerful our family’s dogs and cats with whom we shared our all too familiar with home. the effect diet can choice have on one’s health. However, it wasn’t until later in life that I made the connection between my beloved dog, Sadie, for whom The fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains my diet I would do anything to protect her from abuse and now revolved around made me feel healthier and gave discomfort, and the nameless pigs, cows, and chickens me more energy than ever before. -

Changes of Soybean Protein During Tofu Processing

foods Review Changes of Soybean Protein during Tofu Processing Xiangfei Guan 1,2 , Xuequn Zhong 1, Yuhao Lu 1, Xin Du 1, Rui Jia 1, Hansheng Li 2 and Minlian Zhang 1,* 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Institute of Biochemical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] (X.G.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (R.J.) 2 School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 102488, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +86-10-6279-5473 Abstract: Tofu has a long history of use and is rich in high-quality plant protein; however, its produc- tion process is relatively complicated. The tofu production process includes soybean pretreatment, soaking, grinding, boiling, pulping, pressing, and packing. Every step in this process has an impact on the soy protein and, ultimately, affects the quality of the tofu. Furthermore, soy protein gel is the basis for the formation of soy curd. This review summarizes the series of changes in the composition and structure of soy protein that occur during the processing of tofu (specifically, during the pressing, preservation, and packaging steps) and the effects of soybean varieties, storage conditions, soybean milk pretreatment, and coagulant types on the structure of soybean protein and the quality of tofu. Finally, we highlight the advantages and limitations of current research and provide directions for future research in tofu production. This review is aimed at providing a reference for research into and improvement of the production of tofu. -

DRINKING SOY MILK DAILY DESTROYS YOUR THYROID, CAUSES BRAIN DAMAGE and KIDNEY WELCOME YA’LL STONES Welcome! If You Are

4/14/19, 906 PM Page 1 of 1 Anya Vien HOME BLOG ABOUT WORK WITH ME SHOP DISCLAIMER Search DRINKING SOY MILK DAILY DESTROYS YOUR THYROID, CAUSES BRAIN DAMAGE AND KIDNEY WELCOME YA’LL STONES Welcome! If you are July 13, 2018 / by Anya / 16 Comments interested in the truth about nutrition, then you are in the right place. The ! " # $ key mission of my site is to empower people with factual facts about the toxic chemicals, heavy Our modern society has proclaimed soy milk as the healthiest milk for years. Even most doctors metals, hormone disruptors found in foods, and nutritional experts recommend it as a better milk option. From 1992 to 2006, sales went up medicine, and personal care products. from $300 million to almost $4 billion! Learn more Anya Vien @livingtraditionally All about natural health, alternative medicine, toxic products. Snapchat: anyavien However, nothing could be further from the truth. Around 170 scientific studies prove the ! Follow dangers of soy. Soy products such as soy milk are very toxic and can cause kidney stones, 9,308 Followers 223 Follow thyroid problems, brain damage and breast cancer. Healthy Living with … Like Page 64K likes Be the first of your friends to like this Healthy Living with Anya Vien 12 minutes ago ANYAVIEN.COM How to Get Rid of Ants Over… Baking soda is my favorite natural h… 2 Comment 2 Healthy Living with The Whole Soy Story: The Dark Side of America’s Favorite Health Food Soymilk Ingredients Soymilk (Filtered Water, Whole Soybeans), Cane Sugar, Sea Salt, Vitamin A Palmitate, Vitamin“ D2, Riboflavin (B2), Vitamin B12,Carrageenan, Natural Flavor, Calcium Carbonate.