Pietro Deandrea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 3:07-Cr-00057-MRK Document 6 Filed 03/21/2007 Page 1 of 9

Case 3:07-cr-00057-MRK Document 6 Filed 03/21/2007 Page 1 of 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : Case No: : : VIOLATIONS: : : 18 U.S.C. § 2339A (Providing Material v. : Support to Terrorists) : : 18 U.S.C. § 793(d) (Communicating : National Defense Information to Persons not : Entitled to Receive it) HASSAN ABUJIHAAD, : a/k/a PAUL R. HALL : 18 U.S.C. § 2 I N D I C T M E N T The Grand Jury charges that: INTRODUCTION 1. From on or about December 20, 1997, through on or about January 25, 2002, HASSAN ABUJIHAAD, a/k/a PAUL R. HALL (“ABUJIHAAD”), was an enlisted member of the United States Navy. From on or about July 1, 1998, through on or about January 10, 2002, ABUJIHAAD was assigned to a United States Navy destroyer named the U.S.S. Benfold, where his primary position was Signalman. In March and April 2001, the U.S.S. Benfold was part of a United States Navy Battle Group directed to transit from California to the Persian Gulf region. 2. On January 6, 1998, in connection with his duties in the United States Navy, ABUJIHAAD was approved by the Department of the Navy Central Adjudication Facility (“DONCAF”) for access to information classified at the “Secret” level pursuant to Executive Order 12,958, as amended by Executive Order 13,292. Case 3:07-cr-00057-MRK Document 6 Filed 03/21/2007 Page 2 of 9 3. Pursuant to Executive Order 12,958, as amended by Executive Order 13,292, national security information may be classified as, among other things, “Secret.” The designation “Secret” applies to information, the unauthorized disclosure of which reasonably could be expected to cause serious damage to the national security. -

High Court Judgment Template

Case No: CO/5160/2014 Neutral Citation Number: [2015] EWHC 2354 (Admin) IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 07/08/2015 Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE CRANSTON - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: THE COMMISSIONER OF THE POLICE OF THE Claimant METROPOLIS - and - SYED TALHA AHSAN Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mr Tom Little (instructed by the Metropolitan Police Legal Service) for the Claimant Mr Daniel Squires (instructed by Birnberg Peirce & Partners) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 24/07/2015 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgmen tMr Justice Cranston: Introduction: 1. This is an application by the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (“the Commissioner”) for an order to impose notification requirements for a period of 15 years on Syed Talha Ahsan (“Mr Ahsan”) under the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008 (“the 2008 Act”). In 2013, he was convicted in the United States of conspiracy to provide material assistance for terrorism through his involvement in a website. He has now returned to the United Kingdom. The notification order will require him for that period to attend police stations to provide, and update, information about his living arrangements and to provide details about his travel plans, for which permission can be refused. Breach of the requirements is punishable with imprisonment of up to 5 years. 2. Notification requirements have been imposed in many cases when persons have been convicted in the UK of terrorist-related offences. This is the first case in which a notification order has been contested in respect of a person convicted outside the UK of a corresponding foreign offence. -

Case Number 3:04CR301(JCH) : V

Case 3:04-cr-00301-JCH Document 181 Filed 06/16/14 Page 1 of 30 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : Case Number 3:04CR301(JCH) : v. : : BABAR AHMAD a/k/a “Abu Ammar”, : a/k/a “Abu Khubaib/Kubayb Al-Pakistani” : a/k/a “Salah” / “Salahuddin”, a/k/a : “Dr. Karim”, a/k/a “D. Karim”, a/k/a : “Maria Alcala”, a/k/a “Lara Palselmo” : a/k/a “Mr. B” : JUNE 16, 2014 GOVERNMENT’S SENTENCING MEMORANDUM On July 16, 2014, the Court will sentence the defendant, Babar Ahmad (“Ahmad”), for conspiring to provide and providing material support to terrorists, knowing and intending that such support would be used in preparation for and in carrying out: (1) a conspiracy to kill, kidnap, maim or injure persons or damage property; or (2) the murder of U.S. nationals abroad. Ahmad’s conduct, summarized in part below, warrants the maximum sentence of twenty-five (25) years. From at least 1997 through his arrest in August 2004, Babar Ahmad – through the use of numerous kunyas and aliases – surreptitiously led a sophisticated, highly organized, technically savvy and operationally covert support cell in London with global reach, through which he supported the Chechen mujahideen, the Taliban and Al-Qaida. Ahmad’s material support operation was robust, far-reaching and virtually unprecedented in its scope – indeed, Ahmad and his cell provided almost every single category of support set forth in the material support statute. Ahmad supplied funds, military equipment, communication equipment, lodging, training, expert advice and assistance and personnel – all of which were designed to raise funds, recruit for and provide equipment to the Chechen mujahideen, the Taliban and Al-Qaida, and to otherwise 1 Case 3:04-cr-00301-JCH Document 181 Filed 06/16/14 Page 2 of 30 support violent jihad in Afghanistan and Chechnya. -

Syed Talha Ahsan : June 16, 2014

Case 3:06-cr-00194-JCH Document 179 Filed 06/16/14 Page 1 of 52 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : NO. 3:06CR194(JCH) v. : SYED TALHA AHSAN : JUNE 16, 2014 SYED TALHA AHSAN’S MEMORANDUM IN AID OF SENTENCING I. Introduction Syed Talha Ahsan has now served over eight (8) years in prisons in England and the United States, for his peripheral involvement in a case not susceptible to easy explanation or categorization. He is a highly intelligent, sensitive, inquisitive, creative man, who does not subscribe to violence as a means to solving problems. He is a threat to no one. The odds of his committing any kind of new offense are so low as to be virtually negligible. The parsimony clause of the Sentencing Reform Act would be fully satisfied by a sentence of less than the time which he has already served. Under all the circumstances here, a sentence of credit for time served is appropriate. All of Talha Ahsan’s conduct in this case occurred prior to September 11, 2001 (“9/11"). There is no allegation here that Mr. Ahsan committed or attempted to commit any act of violence. This case is not about al Qaeda. It is a case about a citizen of the United Kingdom, who before his extradition had never set foot in the United States, and the marginal assistance he provided to a website when he was twenty years old. The website reported on the plight of Muslim populations around the world. It provided information on the concept of defensive jihad, i.e., the religious obligation to protect Muslims at risk of genocide and violent persecution. -

The European Angle to the U.S. Terror Threat Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer

AL-QAEDA IN THE UNITED STATES THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Nineteen individuals (11% of the overall total) who committed al-Qaeda related offenses (AQROs) in the U.S. between 1997 and 2011 were either European citizens or had previously lived in Europe. • The threat to America from those linked to Europe has remained reasonably constant – with European- linked individuals committing AQROs in ten of the fifteen years studied. • The majority (63%) of the nineteen European-linked individuals were unemployed, including all individuals who committed AQROs between 1998 and 2001, and from 2007 onwards. • 42% of individuals had some level of college education. Half of these individuals committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2001, while the remaining two individuals committed offenses in 2009. • 16% of offenders with European links were converts to Islam. Between 1998 and 2001, and between 2003 and 2009, there were no offenses committed by European-linked converts. • Over two thirds (68%) of European-linked offenders had received terrorist training, primarily in Afghanistan. However, nine of the ten individuals who had received training in Afghanistan committed their AQRO before 2002. Only one individual committed an AQRO afterwards (Oussama Kassir, whose charges were filed in 2006). • Among all trained individuals, 92% committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2006. • 16% of individuals had combat experience. However, there were no European-linked individuals with combat experience who committed an AQRO after 2005. • Active Participants – individuals who committed or were imminently about to commit acts of terrorism, or were formal members of al-Qaeda – committed thirteen AQROs (62%). -

6 March 2014

6 March 2014 THOUGHT FOR THE DAY THE PTSS DAILY began as a FLASH POINTS means of keeping PTSS Marshall Center Alumni abreast of news GLOBAL STRATEGIC OVERVIEW related to terrorism. THE PTSS SPECIAL: LEGAL ISSUES IN CBT DAILY is neither an academic COUNTERTERRORISM NEWS BY journal nor the effort of a research NATION & REGION directorate or a large staff. Early each morning, articles ALGERIA that are cited in THE PTSS DAILY are culled from AUSTRALIA hundreds of sources with the intent of providing you BAHRAIN with the most current news, discussions and commentary CAMEROON CANADA on terrorism and related issues such as piracy or narco- EGYPT terrorism. These articles, curated from news media, GERMANY academic and international sources or submitted by IRAN many of you, give our growing network a snapshot of IRAQ this pernicious threat. NIGERIA PAKISTAN/AFPAK Every effort is made to ensure that credible articles are PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA chosen, but the intent of THE PTSS DAILY is to deliver QATAR wide coverage. You – the professional – must be the RUSSIA final discriminator on the merit of a particular article and SOMALIA its value to your profession. To ensure that THE PTSS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DAILY is both relevant and valuable to the reader, we AL QA’IDA & AFFILIATES welcome and highly encourage comments from you. COMMENTARY & OPINION CYBER WARFARE GEORGE C. MARSHALL LEGAL ASPECTS & LAWFARE EUROPEAN CENTER FOR SECURITY STUDIES NETWORK NOTES LTG (Ret.) Keith W. Dayton, Director SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY Dr. Robert Brannon, Dean, College of International TERRORIST FINANCING Security Studies WMD TERRORISM PTSS DAILY EDITORIAL STAFF MAJ Daryl DeSimone, Executive Editor Mrs. -

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

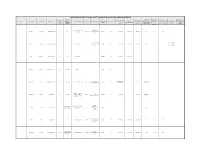

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Watkin Ahmad Ahsan Ruling 3102012

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Judge Howard Riddle, Senior District Judge (Chief Magistrate) Ruling on the application of Mr Karl Watkin MBE for the issue of process -v- Mr Babar Ahmad & Mr Syed Talha Ahsan 3 October 2012 I have considered two informations dated 23rd August 2012 submitted by Ward Hadaway solicitors on behalf of Karl Watkin MBE. Mr Watkin seeks to summons Mr Babar Ahmad and Mr Syed Talha Ahsan to face allegations of solicitation to murder, contrary to Section 4 Offences Against the Person Act 1861. It is said that the two proposed defendants played a leading role in the administration of websites that, among other things, encouraged engagement in violent Jihad, pursing the death of ‘non-believers’ if necessary. Test Section 1 MCA 1980 says:- 1 Issue of summons to accused or warrant for his arrest (1) On an information being laid before a justice of the peace that a person has, or is suspected of having, committed an offence, the justice may issue-- 1 (a) a summons directed to that person requiring him to appear before a magistrates’ court to answer the information, or (b) a warrant to arrest that person and bring him before a magistrates’ court. It will be seen from the section that the justice “may” issue a summons. There is a discretion. That discretion is neither unfettered nor unlimited. In R v West London Magistrates’ Court, ex p. Klahn [1979] 1 WLR 933 it was said: “The duty of a magistrate in considering an application for the issue of a summons is to exercise a judicial discretion in deciding whether or not to issue a summons. -

Evidence from US Experts to the House of Lords Select Committee on the Extradition Law

Evidence from US experts to the House of Lords Select Committee on the Extradition Law 1. We are academics, researchers and legal experts who have studied the US system for prosecuting terrorism-related crimes. Our academic and legal research on the US system has appeared in peer-reviewed journals, books and congressional and legal testimony. 2. We have become increasingly concerned in recent years at the human rights issues raised by the extradition of persons from the UK to the US to face terrorism-related charges. Moreover, we believe that the evidence already submitted to the committee on the nature of the US system conveys an inaccurate picture of how terrorism prosecutions in the US are conducted. In particular, we have deep concerns about the pattern of rights abuses in these cases and the conditions of imprisonment that terrorist suspects face in the US both before and after their trial or sentencing hearing. 3. Given the significant proportion of US extradition requests that involve federal terrorism-related charges and the particular concerns that exist in relation to these, we believe that specific attention to this category of extradition is warranted. In our submission, we have restricted our comments to terrorism- related cases and make no claims about cases involving other kinds of charges, although we believe much of our evidence would apply more widely. 4. We are familiar with a number of terrorism-related cases involving extradition requests to the US from the UK since 9/11: Babar Ahmad, Syed Talha Ahsan, Haroon Rashid Aswat, Adel Abdel Bari, Khaled Al-Fawwaz, Syed Fahad Hashmi, Mustafa Kamal Mustafa (commonly known as Abu Hamza) and Lotfi Raissi. -

Terrorist Trial Report Card 2001-2009

Center on Law and Security, New York University School of Law Terrorist Trial Report Card: September 11, 2001-September 11, 2009 January 2010 Acknowledgments Executive Director of the Center on Law and Security / Editor in Chief Karen J. Greenberg Director of Research/Writer Francesca Laguardia Editor Jeff Grossman Research Jessica Alvarez, Gayle Argon, Daniel Peter Burgess, Laura C. Carey, Andrea Lee Clowes, Casey Doherty, Meredith J. Fortin, Alice Goldman, Matt Golubjatnikov, Isabelle Kinsolving, Tracy A. Lundquist, Adam Maltz, Robert Miller, Lea Newfarmer, Robert E. O’Leary, Jason Porta, Meredythe M. Ryan, Dominic A. Saglibene, Alexandra Ross Schwartz, Moses Sternstein, Nancy Sul, and Jonathan Weinblatt Designer Wendy Bedenbaugh Senior Fellow for Legal Affairs Joshua L. Dratel Faculty Co-Directors of the Center on Law and Security David Golove, Stephen Holmes, Richard H. Pildes, and Samuel J. Rascoff Special thanks to Barton Gellman, CLS Research Fellow. In its formative years, the Terrorist Trial Report Card was supervised consecutively by Andrew Peterson, Daniel Freifeld, and Michael Price. Our gratitude for their work is immeasurable. Thanks also to Nicole Bruno and David Tucker. The Center on Law and Security New York University School of Law 110 West Third Street • New York, NY 10012 • 212-992-8854 • [email protected] Copyright ©2010 by the Center on Law and Security www.lawandsecurity.org i The Terrorist Trial Report Card, 2001-2009 tudying the full eight years of post-9/11 federal terrorism prosecutions, the Center on Law and SSecurity has assembled a massive relational database, a resource that exists nowhere else. Periodically we have reached into the growing data set and pulled out snapshots of the most illuminating trends. -

FOI Letter Template

Counter-Terrorism Department Foreign and Commonwealth Office King Charles Street London SW1A 2AH Website: https://www.gov.uk John Goss [email protected] 07 January 2014 Dear Mr Goss FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 2000 REQUEST REF: 0557-13 Thank you for your email of 11 June 2013 asking for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) pertaining to the extradition of Syed Talha Ahsan. Included in this letter are responses to the 27 questions you raise. The questions and answers have been split into exemptions; those that fall under Freedom of Information and those that do not. I thought you would find it useful if I set out the role Her Majesty’s Government (HMG) plays in extradition proceedings. This will explain why the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) is unable to answer and/or holds no information for some of the questions you pose. The Home Office has the policy lead on implementing the government extradition policy and is responsible for managing extradition case work. The FCO acts as agent for the United Kingdom Government in legal proceedings in the European Court of Human Rights. Given the above, you may wish to consider re-directing some of your questions to the Home Office by email to [email protected]. Questions falling under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 1) Was any contact made with United States representatives of any description to arrange the deportation of Syed Talha Ahsan before the appeal verdict of the European Court of Human Rights had been reached? No information held. -

Violations: : : 18 U.S.C

Case 3:06-cr-00194-JCH Document 1 Filed 06/28/06 Page 1 of 14 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : Case No: : : VIOLATIONS: : : 18 U.S.C. §2339A(Conspiracy to Provide : Material Support to Terrorists) : v. : 18 U.S.C. § 2339A (Providing Material : Support to Terrorists) : : 18 U.S.C. § 956 (Conspiracy to Kill/Injure : Persons Abroad) : : 18 U.S.C. § 371 (Conspiracy) : SYED TALHA AHSAN : 18 U.S.C. § 2 (Aiding and Abetting) I N D I C T M E N T The Grand jury charges that: INTRODUCTION 1. From in or about 1997, the exact date being unknown to the grand jury, and continuing through at least August, 2004, BABAR AHMAD (“AHMAD”), a resident of the United Kingdom, and AZZAM PUBLICATIONS, who are named but not charged herein, along with the defendant SYED TALHA AHSAN (“AHSAN”), and others known and unknown to the grand jury, provided, and conspired to provide, material support and resources to persons engaged in acts of terrorism in Afghanistan, Chechnya and elsewhere. Specifically, AHMAD, AZZAM PUBLICATIONS, AHSAN and others known and unknown to the grand jury, through the creation and use of various internet websites, e-mail communications, and other means, provided: expert advice and assistance; communications equipment; military items; currency; Case 3:06-cr-00194-JCH Document 1 Filed 06/28/06 Page 2 of 14 monetary instruments; financial services; and personnel, all designed to recruit for and assist the Taliban and the Chechen Mujahideen, and to raise funds for terrorist activities in Afghanistan, Chechnya and other places.